On reading AS Panneerselvan’s column on media issues, Readers’ Editor, in The Hindu of 19 August 2013, I felt inclined to dwell on Panneerselvan’s hopes and Shashi Kumar’s efforts. After commenting and expressing his concern over the plight of Dalit students trained in journalism in the Indian Institute of Mass Communication, Panneerselvan goes on to refer to his conversation with Shashi Kumar, the director of the Asian College of Journalism (ACJ), Chennai.

Shashi Kumar told Panneerselvan that since 2004, he keeps in his prestigious institution four seats reserved for Dalits. The Dalit students can even get free lodging and boarding. But he expressed his disappointment over the fact that even these seats remained vacant. Without mentioning the reason for the seats remaining vacant, Shashi Kumar said that the Dalit candidates have to appear in the examination for admission to this entirely free-of-charge course and no relaxation is given to them in terms of qualifying marks. Apparently, Shashi Kumar is too much of a gentleman to say that Dalit students either fail to clear the exam or are unable to obtain the minimum qualifying marks. Shashi Kumar wants that Dalits should get their due place in the world of media and so he is thinking in terms of making arrangements for coaching for these students to help them clear the entrance exam. It is with reference to this plan of Shashi Kumar that the Readers’ editor of The Hindu has expressed the hope that Dalits will gain entry into the newsrooms of Indian media in a big way.

Shashi Kumar’s is a well-known name in the world of journalism and TV. He is also the chairman of Media Development Foundation, which runs ACJ. There are hundreds of institutions in the country running courses in journalism. An estimate suggests that in NCR alone, there are more than 200 such institutions. They charge hefty fees from the students in return for the promise of making them fit for employment in the media. Obviously, these institutions have hardly any social concerns and there is no question of them trying to ensure entry of girls and boys of this or that section of the society into journalism. But Shashi Kumar is not a mere journalist. He is an activist too. His journalism has social concerns.

About a year or two back, I received a call from Siddharth Varadarajan, who was then the Delhi bureau chief of The Hindu. He wanted to know whether I had seen his mail. But what reaction could I have given? Because I remembered that in the preceding year also, Shashi Kumar had issued a similar advertisement. His institute is considered one of the best in the country. But one thing in the ad was rather upsetting. He had sought ‘good and competent’ Dalits for enrolment in his institution. The obvious question was that when he was already using adjectives like ‘good and competent’ then where was the need to append them with the word Dalit? Did it mean that he was trying to ensure the entry of Dalits in his institutions, who did not have any place there till then? Just like favours are granted to the Dalits by opening the doors of Hindu temples for them. But since Shashi Kumar was interested in consistently producing Dalit and tribal journalists, so he went a step ahead and announced full scholarships for them. But he is still not getting Dalit and tribal students. What could be the reason?

Siddharth asked me as to why ACJ was not getting Dalits and tribals as students despite it offering so many facilities and despite its location in a leading city of South India. I told Siddharth that it was due to the lack of knowledge of English that the Dalits and tribals of this area cannot think of joining the institute. Siddharth then told me that the institute also has arrangement for teaching English. That is, the students will be first taught English and then trained in journalism. Despite all these facilities, the institute has not received a single application from Dalit or tribal candidates against 20 seats which could have been allotted to them. It is rather strange that in Indian society, the section which uses and makes its living from Indian languages cares two hoots for Dalits. Even today, there is a small group among the Dalits which worships Macaulay. This group believes that it was due to Macaulay that some people amongst them learnt English and because of that, were appointed to high positions. In this respect, reading the history of journalism in Bengal was an enlightening experience. Samvad Prabhakar was considered a progressive newspaper but in one of its issues it says, “The growing desire among people of lower castes to study English has created a new problem. Now, the boys of carpenter and sweeper families are learning rudimentary English and grabbing posts of clerks, agents and others. They are quitting their family occupation. This is leading to social problems of many kinds.”

It was the English-language journalists who made the virtual absence of Dalits from the media a matter of debate and discussion. It is the English-medium Asian College of Journalism that is keen to give opportunity to Dalit and tribal students to join its courses. Government institutions such as the IIMC do train Dalit and tribal students in keeping with the quota dictated by government rules but these students are hard put to find a job. My personal experience is that Dalit and tribal students trained in journalism hardly get work in any Indian-language publications. There is not a single instance of a person from these communities reaching to the top positions in vernacular publications. Most of the students of these categories are thus forced to take up government jobs. The situation is not very happy in the English media either. In the Northeast, the Dalits and tribals are able to get jobs.

The first question is of the relationship between Dalits and language. Only a small section of the Dalits has been able to learn English. English has been thrust upon India not just as another language but as something synonymous with knowledge and wisdom. English has established itself as the language of the elite class. No wonder, the non-English-knowing section of the Dalits wants to join government jobs. Then, there is also the question of faith and confidence. In the social situation prevailing in the country, it is difficult for Dalits or tribals to have the confidence that they would get job after completing a certain course. This kind of confidence only government institutions can inspire.

The Hindu has close association with ACJ. N. Ram, the editor of The Hindu is one of the directors of the institute. But writing about the newspaper, Ravi Kumar says that not a single Dalit has ever got employment in the editorial department of The Hindu in its 125-year history. Ravi Kumar is the only Dalit Panther MLA in the Tamil Nadu Assembly and is a well-known writer.

Shashi Kumar talks of free coaching and is even ready to help Dalits clear the entrance exam. But the question is of faith – of confidence. That is what Dalits are seeking. Whether it is a question of finding Dalit and tribal students for a journalism school or of employing them as journalists, the structure of Indian journalism is such that they cannot have the confidence that they have a place there. ACJ’s quest for Dalit students can be the subject of an interesting sociological study. Journalists are the suppliers of news and here is a news of and from the world of journalism. In fact, not only the media, but all other institutions which are part of the Hindutva system have lost the confidence of the Dalits. But the question here is not of coming up to the standards of the exam. Exams after exams, freeships after freeships – Shashi Kumar may do anything but the issue is whether he can win the confidence of the Dalits. In the Indian society, whether it is of Shashi Kumar or English – both the structures are considered dominant.

Published in the November 2013 issue of the Forward Press magazine

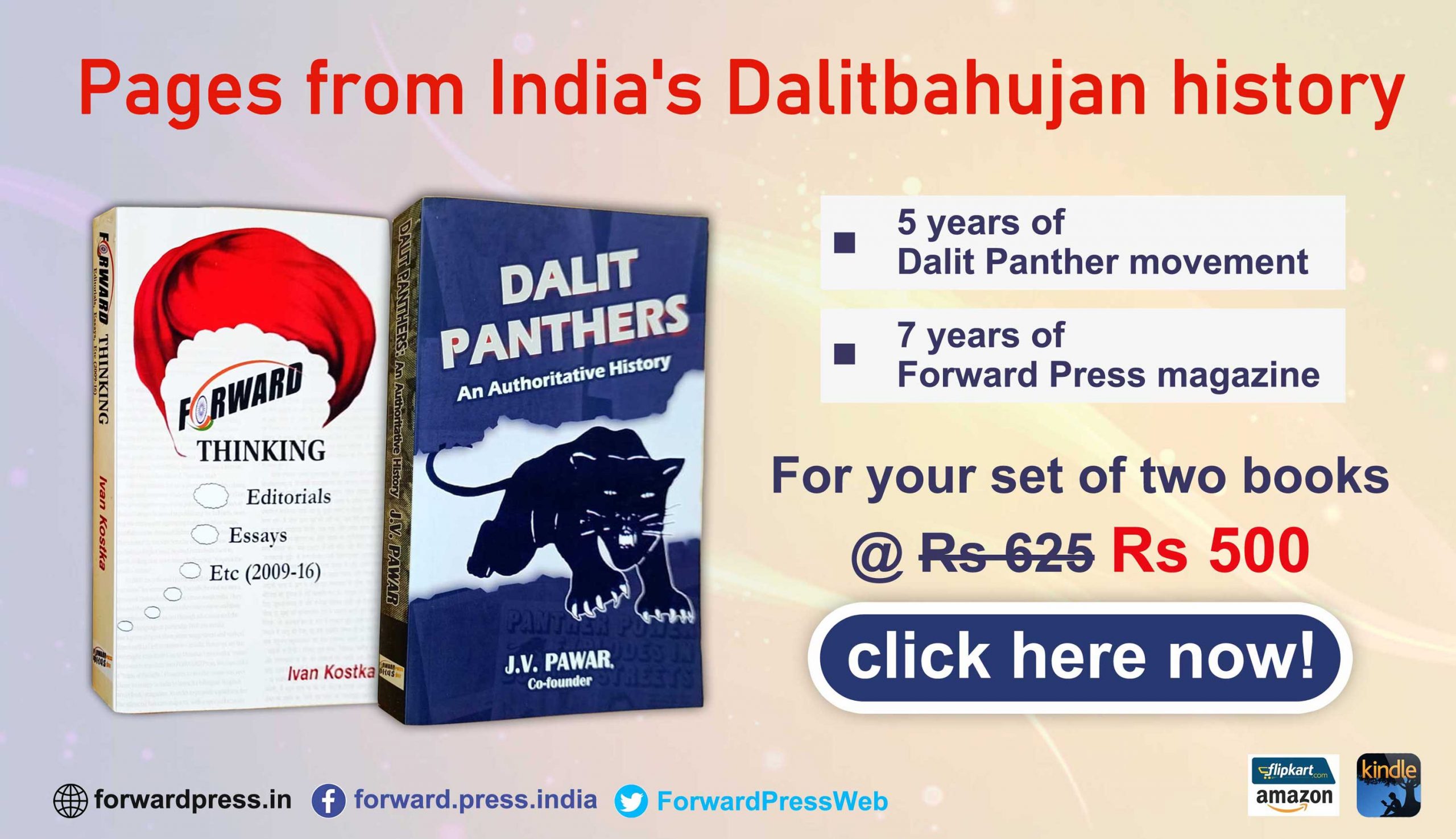

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History