Those who have been described as Shudras in Brahmanical religious texts are today called OBCs. The tales of valour of the heroes and heroines of this class are not found in history or the Puranas. These tales live on through the oral tradition of folklore. Unlike Dwij hero-heroines, the statues of OBC hero-heroines are not installed in temples but in deeh-dihwars (small makeshift mud temples) outside villages and their female warriors in the sati maiya chaura (a place where a woman is supposed to have committed Sati).

I live in a small town, Sasaram, in Bihar. Close by is Karpurwa, a village of the Koire caste. There, statues of innumerable historical personalities are installed on small columns of bricks in the fields. They include Sanwara Veer Baba, Nunwa Veer Baba and Banhva Veer Baba. When there have been so many OBC men of mettle in one village alone, their number in the innumerable villages and hamlets of India can only be imagined. While in some place, you will hear about the romance of Shobha Nayka Banjara, elsewhere, you are told about the valour of the two Yadavs, Manas Gop and Bulaki Gop, and yet another place may introduce you to the beauty of Gaango and Lachiya Panerin.

Lorik:

He was a Yadav by caste. The story of his life and times has become a part of the folklore not only in north India but also in West Bengal and even south India. Chandayan (1379AD), written by Dawood, Mainasat by Sadhana, Mainasatwanti (Dakkhini) by Gavvasi and Lor Chandrani in Bangla written by Daulat Quazi – all relate his tale. In the Maithil area of Bihar, the story of Harwa-Harwa is woven into several folk songs. In Bhojpuri, it is called Loriki. The Mirzapuri version of this folktale has been compiled by W. Crook. The Chhattisgarhi version has been translated into English by Father Verrier Elwin. Thus, Lorik’s character is found in the folk literature of almost all dialects of Hindi. Lorik personifies the great lover and a brave warrior.

He was a Yadav by caste. The story of his life and times has become a part of the folklore not only in north India but also in West Bengal and even south India. Chandayan (1379AD), written by Dawood, Mainasat by Sadhana, Mainasatwanti (Dakkhini) by Gavvasi and Lor Chandrani in Bangla written by Daulat Quazi – all relate his tale. In the Maithil area of Bihar, the story of Harwa-Harwa is woven into several folk songs. In Bhojpuri, it is called Loriki. The Mirzapuri version of this folktale has been compiled by W. Crook. The Chhattisgarhi version has been translated into English by Father Verrier Elwin. Thus, Lorik’s character is found in the folk literature of almost all dialects of Hindi. Lorik personifies the great lover and a brave warrior.

Vijaymal:

He is one of the central characters of the tales of valour related in Bhojpuri folksongs. Vijaymal, who was a Teli by caste, is also referred to as Kunwar Bijai. Like Lorik, he too symbolized medieval bravery and magnanimity. In Vijaymal’s tales, the description of marriage and love takes the backseat while battles occupy centre stage. The folksongs, which are sung only in Bhojpuri, are about a unique combination of romance and valour. Kunwar Vijaymal represents that ideal of Indian bravery which is a combination of maturity, patience and valour.

He is one of the central characters of the tales of valour related in Bhojpuri folksongs. Vijaymal, who was a Teli by caste, is also referred to as Kunwar Bijai. Like Lorik, he too symbolized medieval bravery and magnanimity. In Vijaymal’s tales, the description of marriage and love takes the backseat while battles occupy centre stage. The folksongs, which are sung only in Bhojpuri, are about a unique combination of romance and valour. Kunwar Vijaymal represents that ideal of Indian bravery which is a combination of maturity, patience and valour.

Bala Lakhandar:

He is the key character of the folktale Sati Bihula. The song that tells this tale is sung widely, all the way from the Bhojpur and Mithilanchal regions of Bihar to Bengal, to Basti, Gonda and Gorakhpur districts of Uttar Pradesh. The central character of this folktale is Bihula, who tries everything to revive her dead husband Lakhandar. The tale reminds one of the Puranic story of Savitri and Satyavan. The name of Bala Lakhandar’s father is Chandu Sahu. Obviously, Bala Lakhandar comes from a Sahu family. In the Mithilanchal, this folktale is called Bihula Vishhari and its writer is said to be Kosho Saav. In the Bengali version of this folktale, Chandu Sahu is given more prominence than Bihula. Sati Bihula also includes a description of how Bala Lakhandar gets attracted to the ethereal beauty of Bihula.

He is the key character of the folktale Sati Bihula. The song that tells this tale is sung widely, all the way from the Bhojpur and Mithilanchal regions of Bihar to Bengal, to Basti, Gonda and Gorakhpur districts of Uttar Pradesh. The central character of this folktale is Bihula, who tries everything to revive her dead husband Lakhandar. The tale reminds one of the Puranic story of Savitri and Satyavan. The name of Bala Lakhandar’s father is Chandu Sahu. Obviously, Bala Lakhandar comes from a Sahu family. In the Mithilanchal, this folktale is called Bihula Vishhari and its writer is said to be Kosho Saav. In the Bengali version of this folktale, Chandu Sahu is given more prominence than Bihula. Sati Bihula also includes a description of how Bala Lakhandar gets attracted to the ethereal beauty of Bihula.

Guliya Mai:

An OBC, Gulia Mai belonged to what is now Ghazipur district in Uttar Pradesh. Emperor Ashoka had a pillar erected in her name. That Ashoka was moved to do this shows what a great warrior Gulia Mai must have been.

Sohani:

Sohani is the protagonist of Punjab’s famous love story Sohani-Mahiwal. Devendra Satyarthi has written that Sohani is the daughter of a potter and lives in a village on the banks of the Chenab. Mahiwal, a prince, is bowled over by the beauty of Sohani and decides to stay put just opposite her village. Sohani-Mahiwal is a story of platonic love. Everyday, Sohani swims across the river – using an earthen pitcher to keep herself afloat – to meet her sweetheart. She hides the pitcher in the bushes near the river. One day, her sister-in-law replaces the baked pitcher with an unbaked one. With the name of her lover on her lips, Sohani drowns in the river as the unbaked pitcher melts away. Sohani is a symbol of ideal love.

Sohani is the protagonist of Punjab’s famous love story Sohani-Mahiwal. Devendra Satyarthi has written that Sohani is the daughter of a potter and lives in a village on the banks of the Chenab. Mahiwal, a prince, is bowled over by the beauty of Sohani and decides to stay put just opposite her village. Sohani-Mahiwal is a story of platonic love. Everyday, Sohani swims across the river – using an earthen pitcher to keep herself afloat – to meet her sweetheart. She hides the pitcher in the bushes near the river. One day, her sister-in-law replaces the baked pitcher with an unbaked one. With the name of her lover on her lips, Sohani drowns in the river as the unbaked pitcher melts away. Sohani is a symbol of ideal love.

Dayal Singh:

He is the hero of the Maithili folktale Durla Dayal. In the folktale, Dayal Singh introduces himself: “My name is Durla Dayal, village Bharoda. My father’s name is Vishambhar Sahni and my mother’s name is Gajmoti.” Dayal Singh is not only the valiant folk hero of the Nishads but also the deity of Mallahs (boatmen). He is a Mallah by caste but is an accomplished dancer too – that is why he is also known as natua (dancer). In Angika, he is referred to as Natua Dayal and is married to Amrautia, the daughter of Bhaura Godin. All the sisters of Amrautia have already lost their husbands. So, Dayal Singh travels to Kamakhya to seek divine blessings. After coming back from there and crossing a series of hurdles, he brings his wife home. The tale reveals Dayal Singh’s exemplary courage.

Bisunath:

Bisunath is the central character of the Angika folktale Baba Bisunath. It is believed that Bisunath lived during the reign of Mohammed Shah (1719-48). His father was Baljeet Gop while his mother was Champawati, who lived in Bhitti Chanel Nagar. His younger brother was Avahd Manhaun and his elder sister Bhagomanti. They owned 90 lakh cows. In the month of Magha he reached the village for gauna. After gauna, he started for Bathan, where he lived. On the way, he had to cross the Kosi River. He asked Mohan Mandal to get a boat to take him across the river but Mohan tried to wriggle out of the task by giving some excuse. One day, there was a quarrel between Bisunath and Mohan. On hearing about the quarrel from her son Mohan, an enraged Bhauran sent Lilia, the tigress, to Bisunath. He, however, did not hurt the tigress and allowed himself to be killed, with the name of his mother Gaheli on his lips. Later, when 700 tigers came to the village, people started offering milk to Bisunath, who became a symbol of sacrifice. Though he was very strong and had supernatural powers, he did not harm a female animal.

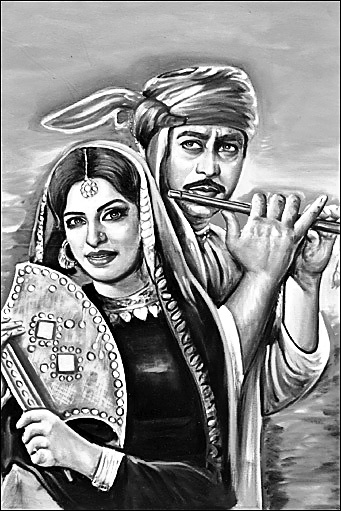

Ranjha:

Ranjha is the hero of the Punjabi folktale Heer-Ranjha. He is born into a Muslim Jat family at a place called Takht Hazare on the banks of the Chenab . He falls in love with Heer, a ravishing beauty who lives at a place called Jhang on the other side of the river. Heer is also in love with him and hence asks her father to hire Ranjha for grazing his buffaloes. Heer goes to the forests every day, carrying delicious food for Ranjha. She is married to a young man, Saida, of Khaida caste, who lives at Rangpur but Heer somehow,manages to remain a virgin. Ranjha reaches the place of Heer’s husband and manages to free her through trickery. Heer returns to her father’s place. Promising Ranjha that he would let his daughter marry him, Heer’s father asks him to come with a baraat. However, once Ranjha leaves, Heer’s father murders her. Unable to bear the shock, Ranjha dies. Heer-Ranjha is one of the immortal love stories of our country.

Ranjha is the hero of the Punjabi folktale Heer-Ranjha. He is born into a Muslim Jat family at a place called Takht Hazare on the banks of the Chenab . He falls in love with Heer, a ravishing beauty who lives at a place called Jhang on the other side of the river. Heer is also in love with him and hence asks her father to hire Ranjha for grazing his buffaloes. Heer goes to the forests every day, carrying delicious food for Ranjha. She is married to a young man, Saida, of Khaida caste, who lives at Rangpur but Heer somehow,manages to remain a virgin. Ranjha reaches the place of Heer’s husband and manages to free her through trickery. Heer returns to her father’s place. Promising Ranjha that he would let his daughter marry him, Heer’s father asks him to come with a baraat. However, once Ranjha leaves, Heer’s father murders her. Unable to bear the shock, Ranjha dies. Heer-Ranjha is one of the immortal love stories of our country.

Sorthi:

Sorthi, a great beauty, is the heroine of a Kaurvi folktale. She belongs to a family of potters. She has a crush on a Banjara called Tapsi and elopes with him. Then the king Oda enters the narrative. He wants to marry Sorthi. He sends his nephew to Tapsi to ‘free’ Sorthi but she then falls in love with the nephew. A battle ensues between the king and his nephew in which the latter is killed but rather than marrying the king, Sorthi prefers to commit sati. Besides Bhojpuri, Sorthi’s folktale is also sung in Maithili and Magahi. Sorthi’s idealism and commitment are central to the story.

Kalar Sundari:

The tale Kalar Sundari or Bahadur Kalarin is told in the form of a song. The story is about a place called Sorar, now in the Balod tehsil of Durg district in Chhattisgarh. In Sorar, Bahadur Kalarin and her son are worshipped as village deities. Kalar Sundari, belonging to the Kalar caste, was extremely good-looking. Mesmerised by her beauty, a prince forcibly marries her and abandons her after she becomes pregnant. A son is born and is named Chacchan Chora. Once he grows up, he realizes how his mother was cheated. Out of revenge, he starts abducting daughters of feudal families and marrying them. He abducts eight Kori girls but he is still dissatisfied. Kalar Sundari, on the other hand, cannot bear to see the pain and distress of the abducted girls. One day, she pushes her son into a well and then commits suicide by stabbing herself with a katar (dagger). The son performs his duty towards his mother, the mother towards society.

These are but a few of the better known folktales of valiant and/or romantic OBCs heroes and heroines. Since most of these largely remain as part of the oral folklore, the challenge is for Bahujan academics to begin to record and document these before they fade away under the onslaught of the mass media. Instead, the media need to harnessed as tools to capture and propagate this rich treasury of our culture.

Published in the October 2014 issue of the Forward Press magazine

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in