I am a citizen

of a country called The Future

where visions are valid visas

and nostalgia but homesickness

for another country called The Past.

When, after five years in journalism in India, I went to America on a fellowship to pursue post-graduate studies in Communications, I wrote a poem “At Home Abroad”. At the heart of that poem, later published in the P.E.N. India journal, were the lines above. I went out, at age 25, just after the Emergency ended, with a dream shared by my photojournalist friend, Mahendra Sinh Rathore, to return to launch India’s first photojournalistic magazine – something like LIFE or LOOK. But my life took a detour and after a few years the vision died. I spent more than a dozen years as a communications and management consultant in North America.

In 1992-93, when I returned to India to start writing a book of short stories, I got two offers to join as editor of magazines, one a photojournalistic magazine like I had imagined. Neither of them worked out for me. During the 1990s I launched and ran a communications agency in Bombay, met and married Dr Silvia Fernandes, a plastic surgeon who had returned after years in Brazil. Ever since then, we have been partners in whatever vision God gives me and wherever He leads us.

Re-vision

The true story of the birth of FORWARD Press cannot be understood without the backstory of a re-visioning of my entire life. Since my late teens, I was a truth-seeker, searching far from my family’s Roman Catholic roots. During a long phase, except in name, I was a Hindu-Buddhist in my worldview. It is out of this phase that in 1985, at age 33, I had an encounter with the truth and, like the young Jotiba Phule, discovered it was a person – the Lord Jesus who claimed, “I am the Truth.”

From my earliest days as a journalist (besides editing college and university student newspapers, at age 18 my first investigative report was published by The Times of India) I always believed in publishing the full facts, naming the names and signing my name – in other words, publish and be damned! Before I was 20 I was twice threatened by the Shiv Sena for my reports. Now, I was called to a higher level, beyond journalistic facts to truth-telling and, even more challenging, “to speak the truth – in love”.

In 2007 my wife and I participated in a “working vacation” for writers in Goa. Towards the end we met a group of Dalitbahujan activists from north India. They shared their agonies within the caste system and their aspirations – to break out through education and the English language in particular. With my media background I gave them some suggestions and wished them well as I left to return to Canada. However, on the overnight train from Goa to Mumbai I received a “vision” that was to translate into FORWARD Press. You can call it a “train of thought”. However, to me the vision was very clear: to return to India to launch a bilingual (English and Hindi) magazine, in order to provide a platform for the silenced Bahujan majority, with a special focus on the voiceless farmers and artisans, who make up the majority of the OBCs. The magazine would address the issues and interests of all Bahujans – OBCs, Dalits, Tribals – from a Phule-Ambedkar perspective. What was very clear to me this time was it was not my or someone else’s vision, it was God’s vision entrusted to me. I took it as a command (khuda ka hukum) and therefore had no option but to obey, whatever the cost. And cost us it did! (For further details, read my wife’s account at the end of this issue.)

Compassion for Dalits

Now, you could well ask, why would God give such a vision to man who grew up Indian without knowing or caring anything about his family’s caste? In fact, to someone who from youth saw casteism as a curse on Indian society? Only God knew what not even his family knew – that from his teens this poet and aspiring novelist and journalist was moved with compassion every time he read of atrocities on the Harijans (as Dalits were called right till the early Seventies). He kept a file of newspaper clippings of such reports, plotting outlines for stories and a novel on the Dalits.

Now, you could well ask, why would God give such a vision to man who grew up Indian without knowing or caring anything about his family’s caste? In fact, to someone who from youth saw casteism as a curse on Indian society? Only God knew what not even his family knew – that from his teens this poet and aspiring novelist and journalist was moved with compassion every time he read of atrocities on the Harijans (as Dalits were called right till the early Seventies). He kept a file of newspaper clippings of such reports, plotting outlines for stories and a novel on the Dalits.

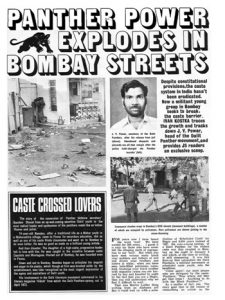

Then, in the early Seventies, at university I started hearing and reading about a group of Dalit Marathi poets and writers who rejected Gandhi’s patronizing label for their people and preferred the Phule-Ambedkar Marathi word “dalit”. Furthermore, inspired by the radical African-American Black Panthers, they called their group the Dalit Panthers.

At age 21, when I started my professional career as a journalist with The Statesman group, I convinced my editor-in-chief, Desmond Doig, to let me report on both the emerging Shiv Sena and the Dalit Panthers. As the Sena “tigers” hunted the Dalit Panthers in Bombay’s urban jungles, the Maratha police joined in attacking the Panthers. I managed to get photographs of policemen in uniforms throwing stones on a Panther parade (morcha) in the working-class BDD Chawls. The photojournalist’s own newspaper did not have the courage to publish them. I persuaded Doig, the last British editor in India, to authorize the purchase of the photos and to caption them without a single “alleged”. These photos accompanied my scoop interview with J.V. Pawar, general-secretary of the Panthers. Pawar was underground when I got to meet him around midnight under a Buddha statue in a Dalit colony near Bombay’s red-light area.

Imagine the pleasant surprise on both sides when, forty years later, a mutual friend put Pawar in Mumbai on the phone to me in Delhi. The first question was if I had a copy of the 1974 interview and article. Since then Pawar has contributed to FP a couple of times including the Cover Story on the Battle of Koregaon.

Documentary on Dalits

For 4 November 2001 when Ram (now Udit) Raj planned to lead a million Dalits to embrace Buddhism, I edited a book The Quest for Freedom and Dignity: Caste, Conversion, and Cultural Revolution and went on to direct an hour-long documentary film Untouchables Vs Aryans: The Battle for the Soul of India. Though the Vajpayee NDA government managed to block lakhs of Dalits from coming from surrounding states into Delhi, on that day at Ambedkar Bhawan around one lakh joined in, converting to Buddhism; the rest followed in other state and district centres. The book was translated and published in six Indian languages. The documentary is still used at various human rights festivals, including Amnesty International’s.

For 4 November 2001 when Ram (now Udit) Raj planned to lead a million Dalits to embrace Buddhism, I edited a book The Quest for Freedom and Dignity: Caste, Conversion, and Cultural Revolution and went on to direct an hour-long documentary film Untouchables Vs Aryans: The Battle for the Soul of India. Though the Vajpayee NDA government managed to block lakhs of Dalits from coming from surrounding states into Delhi, on that day at Ambedkar Bhawan around one lakh joined in, converting to Buddhism; the rest followed in other state and district centres. The book was translated and published in six Indian languages. The documentary is still used at various human rights festivals, including Amnesty International’s.

It was during the making of the documentary that I travelled into the towns and villages of UP and Haryana, met local Dalit activists and simple labourers. I also met leading Dalitbahujan intellectuals and artists and attended for the first time a Dalit Sahitya Sammelan at Delhi’s Talkatora Stadium. It was during this time that I met for the first time Kancha Ilaiah, Sukhadeo Thorat and Gail Omvedt among others.

Broadening to Bahujans

During my time in Delhi working on the documentary film, between 2001 and 2002, I met up with Sunil Sardar, whom I knew earlier when I lived in Pune in the 1990s. A Dalit from Maharashtra who had been involved with the farmer’s movements there, he was the one who at that time pointed me beyond the immediate focus on Dalits. He helped me see the elephant in the Indian room (something obvious but ignored), that without the numerical strength of the OBCs the Dalit struggle against Brahmanism was doomed. In fact, Phule in his emancipatory formulation of ‘stree-shudra-atishudra’ had signalled that 150 years earlier. Ambedkar too echoed that same view. While Ambedkar and his writings had been accessible to me in English, Phule’s work was largely still in Marathi and therefore unfamiliar to me. It was Sunil who introduced me to Phule’s radical life and thought. I took back with me whatever was then available in English on Phule, who was to become one of my greatest heroes. I also took back and read Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not A Hindu (1996), which introduced me to the concepts of the productive castes and of Dalitbahujans.

So, what started in 2001-02 came together in the “train of thought” or vision of January 2007. At that time, while in Goa, I purchased from the Delhi Dalitbahujan group the first edition (2005) of Braj Ranjan Mani’s Debrahmanising History. Besides the writings of Phule and Ambedkar, this ground-breaking book shaped my thinking of the broader Bahujan (shramanic) stream of history, thought and culture. It was Indian history from below, a worm’s-eye view if you like. Little did I realize that the worm was about to turn!

OBCession!

When I arrived in Delhi in early 2008 and announced that I planned to launch a magazine for Bahujans with a special focus on OBCs, most people thought I was crazy. Furthermore, I kept saying I wanted a Bahujan  editor with a Phule-Ambedkar Dalitbahujan perspective. I was told that of the few Bahujans in journalism in north India, those with that philosophical view could be counted on the fingers of one hand! Even H. L. Dusadh of Diversity Mission, whom I met in those early days, confessed from the dais at one of FP’s anniversary celebrations that he had thought I was delusional.

editor with a Phule-Ambedkar Dalitbahujan perspective. I was told that of the few Bahujans in journalism in north India, those with that philosophical view could be counted on the fingers of one hand! Even H. L. Dusadh of Diversity Mission, whom I met in those early days, confessed from the dais at one of FP’s anniversary celebrations that he had thought I was delusional.

It was easier to find willing and qualified candidates from both the Brahmin and Dalit groups. The first but very short-term editor introduced me to Sanjay Kumar, then heading CSDS’ Lokniti division that surveyed India’s electoral behaviour. I asked him if he could contribute a data-based analysis of the “OBC factor” in the General Election of 2009, which was about to begin. He asked me, “Who told you about the OBC factor?” as if I had stumbled upon a political top secret. If I had said God had told me, he might have thought I was even crazier; so I said, isn’t that clear to everybody – especially you? Starting with the Cover Story for the May 2009 FP inaugural issue, this humble political scientist who is now the director of CSDS has contributed most of FP’s major national and key state electoral analyses. The result is that, today, even in the run-up to the UP assembly elections, most of the media reports on the OBC factor in elections.

However, at the end of the day, electorally there is no real OBC vote bloc; it is usually along jati lines that the caste arithmetic is calculated. So it was the Muslim-Yadav-Kurmi consolidation in Bihar that saw Nitish Kumar re-elected. For OBCs to have a sense of corporate identity that transcends their jatis, as Dalits do, there needs to be a new identity that only literature can forge and reinforce. After attending the second All India (mainly Maharashtra) OBC Sahitya Sammelan in Nashik in February 2008, I was inspired to pen a poem ‘Shudra Soul’. I will quote only the final verses:

So, poet, working with words,

take our name

upon the anvil of your art,

beat out the shame,

hammer, hammer away,

until all that is left

is the sharp, shining steel –

a two-edged sword: Shu-dra!

Weld it, wield it

until it carves out our name

upon our very souls.

Then, we shall speak

– yes, sing and shout

our names, our stories, our history –

for we shall know

without a doubt

who we are.

Bahujan literature

In April 2011, at the very end of the FP second anniversary celebrations, Pramod Ranjan was introduced to me as possibly the editor I had been looking for. The very next day, meeting in my Nehru Place office, I discovered he not only had a Hindi-journalism background, he was a keen student of diversity (or lack of it) in the media, and, most significantly, was a literary person at heart. When I talked about Bahujan literature it immediately resonated. Together we crafted what was to become FP’s first Bahujan literature annual in April 2012. As I wrote in the May 2016 Forward Thinking, “Pramod Ranjan … and I have agreed from the beginning that the work of literature has a far deeper and longer-lasting effect than journalism.”

To get the ball rolling we launched with the stalking horse of “OBC literature”. Rajendra Prasad Singh was a major contributor to this stream of the discourse that managed to establish, through debate and discourse over the past few years, that there can be no Bahujan literature without the literature of the OBCs, as much as it must include the literatures of Dalits and Tribals. Though the debates continue beyond the pages of FP, Bahujan literature has come to stay, as much as Dalit literature had even earlier.

Evolving readership, contributors

When FP was launched in 2009 with 100,000 copies mainly distributed across the ten Hindi-speaking states of north India (what I called ‘Hindi-stan’), following in Kanshi Ram’s footsteps, we targeted mainly OBC and Dalit groupings. However, the majority of the early adopters (as they say in marketing) were Dalits and Dalit-dominated Bahujan organizations like BAMCEF. Within six months I was invited to address the thousands at BAMCEF’s annual gathering in Chandigarh. My wife and I regularly attended Ambedkar (and less often, Phule) Jayanti celebrations across Delhi and the surrounding states. I got to speak and she usually set up a magazine table. One of the constant questions we both faced was, if you are not Dalits then why are you doing this?

As FP’s OBC focus developed, Dalits outside of the BAMCEF Phule-Ambedkar umbrella, would complain to me: Why are you wasting time on the OBCs? They are the enemies of the Dalits! I would reply, would you like to see OBCs recognize that you are brothers and sisters with a common oppressor who has divided you in order to continue to rule over you? Not one Dalit said no, even if they thought this was impossible.

Gradually, more and more OBCs, even in remote towns and villages, began to discover and read and discuss FP. More and more, OBC intellectuals and writers who had been content to be classified as Dalit, began to clearly assert their OBC identity while maintaining solidarity with Dalits and Tribals. Today FP is recognized as a Dalitbahujan journal with a focus on OBCs, especially the most marginalized – the Most Backward Castes.

In the early years almost 80 per cent of the contributions were in English. Today it has reversed! While the majority of the contributions are by Bahujans, including Adivasis, increasingly like-minded Savarna intellectuals and writers have been contributing to FP. Most recently, they have been writing specifically for FP, not just a rewrite of a piece published in some other leading journal. In recent years, FP has come to be recognized as one of the top Hindi magazines. You could say at seven years, FP has come of age.

When a caterpillar turns into a chrysalis the ignorant may say the caterpillar has died and the chrysalis betrays no sense of life. However, when the butterfly emerges, spreads its colourful wings and flies – that is really when its life has just begun. So also, don’t mourn for the passing of the seven-year-old FP print magazine. Behold, already one wing is spread out across the globe through the Internet; the other wing is about to emerge as print and e-books every quarter. Rejoice! It’s FORWARD Press in its latest avatar.

In the same way, I dream of the day when – with FP’s contribution being only the latest in a long chain of Dalitbahujan thinkers and activists – the dream of Buddha and Kabir, Phule, Periyar and Ambedkar, among others, will come to full realization: a land of free people where caste has been annihilated and where truly liberty, equality and fraternity reign.

When it’s all been said and done

That is the title of a favourite song of mine that I have requested be played at my funeral. To tell the complete story of these seven years of FP would take a short book or at least a series of articles. The workload and the accompanying stress have taken a toll on my health. As a result, the PhD I started 8 years ago has been indefinitely shelved. Over these years, at various Bahujan forums I have received “honorary doctorates” just by being introduced as “Dr Ivan Kostka”! The love and respect I have received from so many, no money or degrees can buy. Last year, I accepted the invitation to become a member of the National Advisory Council of the Forum for SC/ST Legislators and Parliamentarians.

To me the ultimate reward will be to be able to say, I was not disobedient to the vision given to me. And for the words of that song at my funeral to ring true:

When it’s all been said and done

There is just one thing that matters.

Did I do my best to live for truth?

Did I live my life for you?

Published in the final print (June 2016) issue of the Forward Press magazine