One need not be a rocket scientist to understand that the ruling class and its cohorts, and the owners of property, have always been in the minority. In the monarchial and feudal systems of governance, power has always been in the hands of the elite minority. That is what the concept of oligarchy is. The ruling and the privileged classes never talked of “Bahujan hitay, Bahujan sukhay”. The minority has always been exploiting the majority through state power, by drafting laws suited to their interests, and has been thrusting its literature and its ideology on society. Still, nowhere has the majority allowed its creative urge to die. That is because, besides fulfilling his material needs, man has always been fighting to protect his honour and identity. Social and ideological struggles have emerged from this struggle. Needless to say, the different streams of literature are manifestations of these struggles. In Hindi, the Nath and Siddha literatures emphasize social equality. Subsequently, the Bhakti poetic stream broke up into many sub-streams, including Nirgun and Sagun. Today, the minority starts fuming at the very mention of OBC, Tribal, Dalit and Women’s literatures. It cannot stand the cultural expressions of the backward, toiler communities. Neither can it see the renaissance inherent in them. But this makes no difference to Bahujan literature.

By coining the slogan “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity”, the French Revolution (1789) opened the doors for the establishment of bourgeoisie democracies. The French Revolution had an impact on the entire world. Besides the ruling class and its hangers-on, the nation also has a vast body of toilers that includes farmers, artisans, agricultural labourers, weavers, handicraftsmen, ironsmiths, coppersmiths, leather workers, animal rearers and traders. They are both the castes and classes of the Bahujans. The feudal system survived on land revenue and trade tax. The farmers were the most exploited class. They not only had to pay land revenue but also work without wages.

By coining the slogan “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity”, the French Revolution (1789) opened the doors for the establishment of bourgeoisie democracies. The French Revolution had an impact on the entire world. Besides the ruling class and its hangers-on, the nation also has a vast body of toilers that includes farmers, artisans, agricultural labourers, weavers, handicraftsmen, ironsmiths, coppersmiths, leather workers, animal rearers and traders. They are both the castes and classes of the Bahujans. The feudal system survived on land revenue and trade tax. The farmers were the most exploited class. They not only had to pay land revenue but also work without wages.

Celebrated French novelist Honoré de Balzac (born into a peasant family in 1799, died in 1850) began the trend of portraying the life of the peasants in literature. We can also call him the harbinger of realistic novels. His novel The Peasantry, also translated as Sons of Soil, portrays the merciless exploitation of the poor farmers of France and the capitalist transformation of feudal land relations, and exposes the landowner-moneylender-contractor nexus and its conspiracies. The chief protagonist of the novel is an agricultural labourer. He steals wood from the forests of the feudal lords. He also stealthily catches fish from their ponds. But that does not bring about any change in his extreme poverty. The hero Fourchon tells Blondet, “The colonels live by the solider, just as the rich folks live by the peasant …We are condemned to dig the soil forever. There, where we are born, there we dig it, that earth! And spade it, and manure it … The masses will always be what they are, and stay what they are. The number of us who manage to rise is nothing like the number of you who topple down! …You want to remain our masters, and we shall always be enemies …You have everything, we have nothing; you can’t expect we should ever be friends.” Here, Balzac is dwelling on the social and economic contradictions of the bourgeoisie system, besides analyzing the dynamics, destiny and conflicts of class.

Oriya novelist Fakir Mohan Senapati (born into the Mal caste) wrote the classic Chaman Aath Guntha (1902). It depicts the exploitation and oppression of farmers, weavers and handicraft workers. The British government promulgates a law that deprives farmers of the land they are tilling for hundreds of years. The government also stops the circulation of “kaudi”, the local currency. Due to the unavailability of the new currency, the farmers are unable to pay the land revenue, and the ancestral lands of thousands of farmers are auctioned off. Overnight, moneybags and aristocrats of Kolkata become landlords of Odisha. The novel shows how a cruel and crafty man gets hold of the eight “bigha” land and the cow of a weaver called Magia. Thirty-three years after the publication of this novel, Munshi Premchand exposed the inhuman behaviour of priests and landlords in his novel Godan (1935) through the life of a backward farmer called Hori Mahto. The priest grabs the cow of Dhania citing religious reasons. Many have worked on the women and Dalit discourse in Premchand’s literature but they look askance when asked about the OBC discourse – this, when Hori Mahto and Bhola Ahir are Kushwaha-Kushvanshi and Yadav-Yaduvanshi, respectively. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata were based on the lives of their ancestors. In Godan, Premchand shows us the economic strategy used by the savarna exploiters to turn a farmer into a labourer. Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie (1936), written in English, is a sensitive and moving portrayal of a poor farmer turning into a daily-wage labourer. The hero of the novel is Munnu, who has no fixed source of income. He works as a domestic worker, a coolie, a factory worker and rickshaw-puller at different times to make ends meet. He contracts tuberculosis and dies an untimely death. Hori Mahto, caught in the vicious cycle of debt, suffers a heat stroke while working in his field and dies. The Kurmi farmer in Premchand’s story Balidan commits suicide. Hori Mahto lived in British India, but even after Independence, unable to bear the burden of loan, hundreds of farmers are killing themselves. The backward farmers are worse off.

Oriya novelist Fakir Mohan Senapati (born into the Mal caste) wrote the classic Chaman Aath Guntha (1902). It depicts the exploitation and oppression of farmers, weavers and handicraft workers. The British government promulgates a law that deprives farmers of the land they are tilling for hundreds of years. The government also stops the circulation of “kaudi”, the local currency. Due to the unavailability of the new currency, the farmers are unable to pay the land revenue, and the ancestral lands of thousands of farmers are auctioned off. Overnight, moneybags and aristocrats of Kolkata become landlords of Odisha. The novel shows how a cruel and crafty man gets hold of the eight “bigha” land and the cow of a weaver called Magia. Thirty-three years after the publication of this novel, Munshi Premchand exposed the inhuman behaviour of priests and landlords in his novel Godan (1935) through the life of a backward farmer called Hori Mahto. The priest grabs the cow of Dhania citing religious reasons. Many have worked on the women and Dalit discourse in Premchand’s literature but they look askance when asked about the OBC discourse – this, when Hori Mahto and Bhola Ahir are Kushwaha-Kushvanshi and Yadav-Yaduvanshi, respectively. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata were based on the lives of their ancestors. In Godan, Premchand shows us the economic strategy used by the savarna exploiters to turn a farmer into a labourer. Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie (1936), written in English, is a sensitive and moving portrayal of a poor farmer turning into a daily-wage labourer. The hero of the novel is Munnu, who has no fixed source of income. He works as a domestic worker, a coolie, a factory worker and rickshaw-puller at different times to make ends meet. He contracts tuberculosis and dies an untimely death. Hori Mahto, caught in the vicious cycle of debt, suffers a heat stroke while working in his field and dies. The Kurmi farmer in Premchand’s story Balidan commits suicide. Hori Mahto lived in British India, but even after Independence, unable to bear the burden of loan, hundreds of farmers are killing themselves. The backward farmers are worse off.

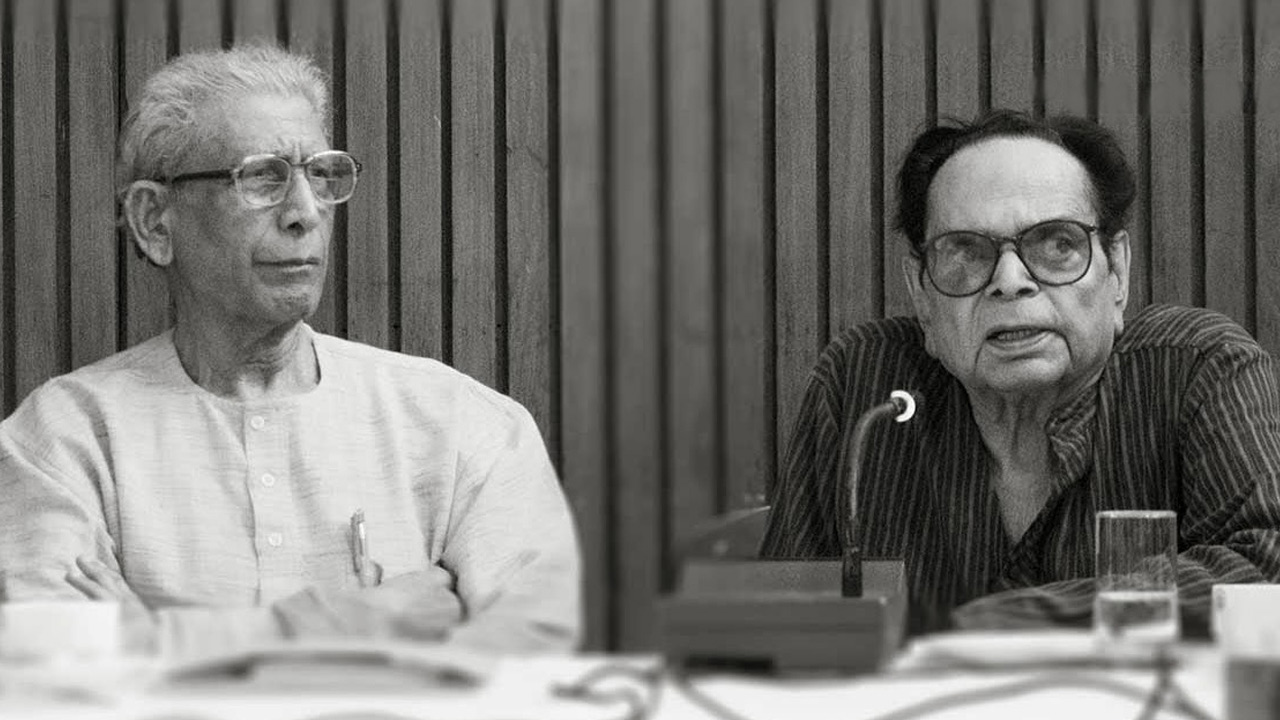

This class has been subjected to economic exploitation and social injustice from time immemorial but at the same time, it is also true that this class has been the main force behind economic and socio-cultural struggles. In Marxist terms, this class is the inspiration and the driving force of class struggle. Not only in the past but even today, it is battling the forces that are out to deprive it of its land and livelihood. Whatever happened or is happening in the Naxal areas and in places like Singur is the outcome of the inhuman acts of the exploiter forces. If the history of human race is the history of class struggle, the history of literature is also the history of ideological and cultural struggles of different classes. What is required – and intellectual honesty demands – is a reappraisal of the literary streams and their dispassionate and ruthless analysis and study. Famous Marxist critic Dr Namvar Singh has identified a second literary tradition, which is different from the tradition Acharya Hazari Prasad Dwivedi talks about. His endeavour represents a quest for continuity and change. In this tradition, the literary creativity of the Backwards and the Dalits, which is part of their struggle, has gained prominence.

Marxism has changed the way we look at history and literature. Marxism says that the means, forces and relations of production form the base on which the superstructure of politics, literature, philosophy, culture, religion, law is built and stands. A change in the base leads to a change in the superstructure and these changes are born out of needs and aspirations. Farmers and workers are the two main classes associated with production and construction, and are the foundations of society. That is why progressive intellectuals try to look at history from the bottom up. This approach is very evident in the writings of Dr Rajendra Prasad Singh. He has given a systematic shape to the concept, language, style, aesthetics, objectives and concerns of OBC literature. He writes, “OBC literature is the literature of only the socially and educationally backward classes…OBC literature is old, the discussion on it is new. Just as gravitational force existed before Newton discovered it, OBC literature also existed before it was named as such.” Rediscovering the literary streams and categorizing them on the basis of their subject matter and specific characteristics is the scientific methodology of research in the humanities. Dr Rajendra Prasad Singh’s Hindi Sahitya Ka Subaltern Itihas is a product of this research methodology coupled with progressive thinking and reflection. It is a seminal work on OBC literary discourse. He is the originator of this discourse and has a profound critical vision. He has attempted a re-evaluation of the authors of Siddha literature, including Meenpa, Kamaria, Tantia, Charptipa, Kantlipa, Mekopa, Bhalipa, Udhyalia and Tilopa, respectively. All of them belonged to the OBC category.

Marxism has changed the way we look at history and literature. Marxism says that the means, forces and relations of production form the base on which the superstructure of politics, literature, philosophy, culture, religion, law is built and stands. A change in the base leads to a change in the superstructure and these changes are born out of needs and aspirations. Farmers and workers are the two main classes associated with production and construction, and are the foundations of society. That is why progressive intellectuals try to look at history from the bottom up. This approach is very evident in the writings of Dr Rajendra Prasad Singh. He has given a systematic shape to the concept, language, style, aesthetics, objectives and concerns of OBC literature. He writes, “OBC literature is the literature of only the socially and educationally backward classes…OBC literature is old, the discussion on it is new. Just as gravitational force existed before Newton discovered it, OBC literature also existed before it was named as such.” Rediscovering the literary streams and categorizing them on the basis of their subject matter and specific characteristics is the scientific methodology of research in the humanities. Dr Rajendra Prasad Singh’s Hindi Sahitya Ka Subaltern Itihas is a product of this research methodology coupled with progressive thinking and reflection. It is a seminal work on OBC literary discourse. He is the originator of this discourse and has a profound critical vision. He has attempted a re-evaluation of the authors of Siddha literature, including Meenpa, Kamaria, Tantia, Charptipa, Kantlipa, Mekopa, Bhalipa, Udhyalia and Tilopa, respectively. All of them belonged to the OBC category.

Dr Singh also refers to the male and female writers of Santkavya in Marathi and Hindi and of Sarbhang Kavya in Hindi, who were all OBCs. All these writers were staunch opponents of the caste system and powerful proponents of humanism. In a Russian work of fiction, a character says, “Priests keep filling our minds with rubbish and defiling our souls.” The Hindu priests have also been filling our minds with the rubbish of fatalism, casteism, varna system, rebirth, heaven and hell, and higher and lower. The OBC litterateurs have taken a tough stand against these nonsensical concepts and Dr Singh does a fine analysis of their writings from this angle. These literary struggles are linked with the cultural struggle, which, in turn, is a ceaseless dialectic of building and breaking social and political domination. OBC literature is the cultural stream of this ceaseless dialectic that is flowing unhindered. Shallow and phony critics keep on issuing diktats to kill this discourse in the womb. Do they think it is that easy?

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)