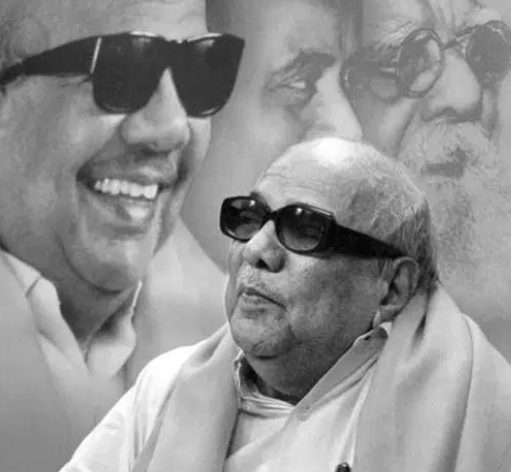

The day M. Karunanidhi was laid to rest, a local television channel followed his cortege through the day, interspersing shots of people paying their respects to the departed leader with interviews of writers, actors, leaders of other political parties … If there was one phrase that was heard repetitively, it was “social justice”. For some, the phrase translated as the welfarism that Karunanidhi’s government put in place from as early as 1969 and that had the wellbeing of the poor in focus. For others, social justice obviously had to do with Karunanidhi’s investment in the reservation policy – of quotas for the backward classes and Dalits, and within the former, sub-quotas for most backward castes, denotified communities, Christians and Muslims. For yet others, Karunanidhi stood for social justice because he upheld the cause of the Tamil language, in the face of attempts by various Union governments to impose Hindi as a language of rule and education.

It can be safely said that Karunanidhi’s own sense of social justice had most resolutely to do with caste-based injustice. Being from a socially stigmatized community, associated with practices of temple dedication, subtle and gross aspects of discrimination and exploitation must have been all too familiar to him. Further, during his boyhood (in the late 1920s and early 1930s), the Self-Respect Movement was actively present in Tamil civic life, and denunications of faith, Brahmin hegemony and the indecencies of caste were urged from the stage, in newspapers and in everyday conversations. Unsurprisingly, Karunanidhi took to featuring these themes in his writings from as early as the 1940s, distilling, as it were, an available mess of rich ideas for a new generation – for people like himself, who had grown up in the heyday of the Self-Respect Movement and were now enthused by the possibility of taking its ideas far and wide through the evolving modern stage and film.

Further, in the late 1940s, standard self-respect themes acquired a distinctive edge. For, this was when Periyar had taken over leadership of the old and almost moribund Non-Brahmin Justice Party, renamed it the Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) and galvanized it into social action in favour of a sovereign Dravidian nation. To him and his Self-Respecters, the Dravidian nation was, in essence, a society free of the authority of the Brahmin and Bania, and the guiles of Brahminical Hinduism. For Periyar, this was not merely a question of upholding the right to national self-determination but of thinking through an alternative vision of the nation, and one that was not captive to Brahmin-Bania interests.

For young men like Karunanidhi, this moment of Dravidian nationalism proved opportune. He – and some others – came to redefine the politics of social justice as an affective politics of Tamil pride as well as a critique of Aryan-Brahmin-Sanskrit-Hindi culture. In Karunanidhi’s able writings, this critique also morphed into a critique of the political ambitions of Indian nationalism.

Parting ways with Periyar

In 1949, a group of men headed by C.N. Annadurai decided to break away from the DK to form their own party. Karunanidhi was part of this group. They claimed they were anguished by Periyar’s marriage to a woman much younger than him. Be that as it may, it was evident there were other reasons: Annadurai was both uneasy with Periyar’s spirited, acerbic and rigorous criticism of Indian Independence and intrigued by the possibilities of electoral democracy which were sure to open up in free India. In Karunanidhi’s case, being part of the DMK, and one of its ablest ideologues, meant that he employed his considerable talents as writer and speaker to gather support for the new party. He was adept at this task, and along with a growing group of young ideologues, some of whom were highly educated, he travelled widely across Tamil Nadu, speaking, organizing and building for himself a role and constituency within the DMK. The 1950s were crucial in this respect in that the basis for the party’s future growth was laid during this time.

The DMK came to power in 1967, wresting power from the Congress, and Annadurai became the chief minister. Karunanidhi was appointed minister for public works but he continued to play his role as party publicist and organizer. When Annadurai passed away in 1969, he was ready to step into his mentor’s place, and did so with alacrity, becoming chief minister the same year. He had to face elections, though, in 1971 but he and his party won handsomely. The beginning of the 1970s may be reckoned the period of Dravidian rule in earnest.

In office, Karunanidhi was faced with the challenge of translating ideals into practice: as an opposition party that had urged the case of Tamil self-rule within the Indian Union, the DMK had proved popular. With the linguistic reorganization of states in 1956, its political instincts regarding language and culture in free India appeared to have been affirmed. Yet the Indian state was not an ideal federal polity, and authority, especially to do with economic planning and development, clearly lay with the Union government. How was one to act within the limits imposed by the latter and yet redeem promises made to an eager electorate?

Karunanidhi: Dravidian-Bahujan hero who took on the Aryan culture

Karunanidhi chose his battles carefully: social justice; initiatives to do with Tamil language and culture; and welfarism that was not entirely dependent on economic growth but could be seen as a crucial aspect of state investment in the public good. Meanwhile, he worked at stratagems to secure Tamil Nadu’s economic interests as well, though this proved less tractable and brought him into conflict with an emergent labour movement in the state.

I will restrict myself here to the DMK’s interventions in the cause of social justice. In 1969, barely a few months in power, he set up a Backward Classes Commission – headed by A.M. Sattanathan – to enquire into the status of these classes in the state, with a view to revamping the reservation policy. Based on its findings, his government increased reservation for these classes from 25 per cent to 31 per cent. Reservation for Dalits was enhanced by 2 per cent taking it to 18 per cent. The Sattanathan Commission had divided the backward classes into two group: backward castes and most backward castes and recommended 16 per cent reservation for the former and 17 per cent for the latter. This distinction was not maintained when Karunanidhi’s government increased the quota from 25 per cent to 31 per cent.

The 1970s saw the backward-designated Vanniyars (a peasant community comprising largely of marginal farmers and tenants) campaigning for a higher share of the reservation quota; and this was a period when the DMK had been voted out and the AIADMK under M.G. Ramachandran was in office. When the DMK returned to power in 1989, it took stock of what had transpired by way of agitations, with Karunanidhi being particularly watchful of the rise of a distinctive Vanniyar voice in the political sphere. On the other hand, being sensitive to how caste identities block or enable access to education and government employment, he was not averse to addressing their concerns. Further, M.G. Ramachandran’s government had already expanded the backward classes’ quota – to 50 per cent – in an attempt to live down an earlier attempt to fix an income criterion for reservation. Keeping with what had happened, and in response to the Vanniyar agitations, Karunanidhi’s government carved out a 20 per cent quota for them within the backward classes category. An additional quota of 1 per cent was fixed for the Scheduled Tribes, who were henceforth not to be considered only within an overall scheduled castes and tribes list. Interestingly, after public furore over the findings of the Sachar Committee – tabled in Parliament in 2006 – Karunanidhi’s government introduced a quota for the backward class Muslims within the general backward classes quota! And in 2008, in response to claims put forth by the Arundathiyars, a Dalit community, he agreed to carving out a quota within the overall 18 per cent meant for the Scheduled Castes.

Sensitivity to graded inequality

The point is that Karunanidhi was quick to recognize that the backward classes were internally differentiated and that had to be accounted for in administrative as well as justice terms. He refused to entertain an income criterion – the so-called creamy-layer argument – and preferred to concentrate on establishing levels of backwardness. He would resort to a similar argument to make his case for a separate quota for the Arundathiyars. Here again, his argument would proceed from considerations of their “backwardness” with respect to income, access to education and state service, within the larger category of so-called Untouchables.

Such decisions were also influenced by political considerations. This is evident when we compare the opportunist manner in which the AIADMK has addressed caste-based reservation, enhancing quotas, without actually working through the logic of graded inequality, except to blatantly favour particular caste communities. Also, the DMK under Karunanidhi has not relied on a particular dominant caste to garner support, unlike in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which have seen backward castes’ assertion.

While caste continues to be a salient feature of electoral politics, the DMK’s political rhetoric of Tamilness and social justice has ensured that the party is not identified with this or that community – a fate that the AIADMK has not been able to forestall, since at any given time it must balance the claims of dominant castes from the north, south and western Tamil Nadu. These castes are “represented” in the DMK as well, but seldom are they vocal in their claims, and neither is the party viewed as endorsing the claims of the one over the other, as was the case with the AIADMK under both M.G. Ramachandran and Jayalalithaa.

Interestingly, Karunanidhi’s sensitivity to the logic of “graded inequality” was not always supplemented with political or social debates on these matters and how they played out in everyday life, or with respect to caste-related discrimination against Dalits in other spheres. It is not that he was not concerned with these latter, but he did not really seek to wage major ideological battles on this score or to convince civil society of the continuing and disastrous consequences of caste-based discrimination, except in and through a generalized anti-caste rhetoric.

In the heyday of the Self-Respect Movement, entreaties for state action or for policies to do with social justice were always accompanied by public debate, civic campaigns and agitations. These had to do not only with this or that demand with respect to social justice but also with the hold of caste, faith and brahmanical precepts in social and cultural matters. However, when a decidedly non-Brahmin party came to power on the basis of an equalizing and putative Tamil identity, it appeared that caste-based discrimination would be addressed by the government, and civil society need not subject itself to critical debates as intensively as earlier.

Further, as I have noted above, the Self-Respect Movement’s concerns were translated into an affective cultural language in the 1940s, and the young ideologues of the DMK were chiefly responsible for this translation. Tamils were asked to reshape their sense of self, based on their ancient pre-varna past, and the literature and ethics associated with key texts from that period, including Jaina and Buddhist literature. It was argued that once they understood their historical identity, they would cease to be casteist and practise equality and fraternity.

Karunanidhi had a key role to play in establishing the coordinates of this Tamilness: through his writings and speeches, replete with quotes from ancient Tamil literature, he took on the brahmanical culture and Hinduism, and substituted for it a distinctive Tamil ethos that drew on an array of classical literary texts. He made available this ethos in a language that could be easily understood. Thus it was generations of Tamils, from the 1950s onwards, who enthusiastically proclaimed their anti-caste politics or at least their disinterest in expressing their caste identities through an invocation of shared Tamil values. Dalits were drawn to the DMK for precisely this reason: that they could unite with others as fellow Tamils and since through the 1950s and 1960s, the DMK did agitate around issues of caste across the state, it did seem that Tamilness would edge out caste!

Therefore, discussions of caste did not appear germane except of course for Dalits who were politicized through Ambedkarite and Left parties, and kept such discussions going. However, these did not gain great public attention, until the 1980s, when a new generation of feisty Dalit leaders and ideologues rendered caste and untouchability matters of public concern, as in the 1920s and 1930s. This generation of Dalits also took issue with Tamilness since a shared cultural heritage had not always and everywhere meant that Dalit claims on equality were respected; worse, they were disregarded and punished.

Response to Dalit (re)assertion

Karunanidhi’s response to this historical moment of Dalit (re)assertion was equivocal. While he formed alliances with Dalit parties to win elections, he did not always respond with urgency to Dalit rights claims, especially in the context of atrocities, or police violence. While he was ready to entertain complaints, he did not often act on them with alacrity, as was made clear with respect to Dalits killed in police firing in what has come to be known as the Tamarabarani killings (1999). Neither did his government act on the massive violation of rights of Adivasis in the context of police and special force action against the so-called sandalwood smuggler, Veerappan. On the other hand, as we have seen, he was not a votary of dominant caste politics, and he has responded to the claims of subaltern castes.

It can be said that a politics of social justice that is urged forth in and through a politics of quotas is productive no doubt, but not adequate to addressing the multiple inequities of caste. To Karunanidhi’s credit, he has not been sanguine about what reservations offer, and in the 1970s did take the battle into the realm of faith, when his government drafted an Act to throw open the hereditary office of the priesthood, hitherto confined to members of the Brahmin community, to all. The Act was challenged in the Supreme Court and allowed passage years after it was originally tabled.

During subsequent terms as chief minister, Karunanidhi has been critical of faith-based politics, much in evidence during the Sethusamudram project, which has to do with a bridge being built to Sri Lanka (even though he entered into an alliance with the BJP in 1999, a decision he was to greatly regret later). Hindutva ideologues were cautious and wondered if such a bridge would not interfere with “Rama’s bridge” of puranic fame! Karunanidhi not only criticized such assumptions, but refused to allow them the status of an argument. Yet on the subject of continuing caste violence, he did not rework terms of understanding and analysis.

Yet, for all that, till the very end, Karunanidhi remained mocking and sceptical of faith, just as he remained alert to caste-based discrimination. The legacy he has left behind is mixed, and even problematic in that there was a distinct lack of direction and vision in his last term in office. Yet it is up to us to critically reflect on and renew historical memory, without being either condescending or nostalgic.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History