There is a proverb that says, “Every cloud has a silver lining.” For millennia, a large population in India has been subjected to suppression. Denied the status of human beings, they were deprived of all their human rights. They were shackled, enslaved and kept in conditions far worse than that of animals. As the eras passed, one dynasty replaced another, resulting in prolongation of the servitude of the masses. Meanwhile, sparks of fury and rebellion kept flaring up amid them, which from time to time assumed bigger proportions. But they were ruthlessly suppressed. However, although suppressed, the rebellion smouldered on. But the history of India has also witnessed such times[1] when the suppression weakened, allowing the enslaved to vent their anger and revolt. It paved the way for a struggle, which, in the 20th century, expanded into a revolution.

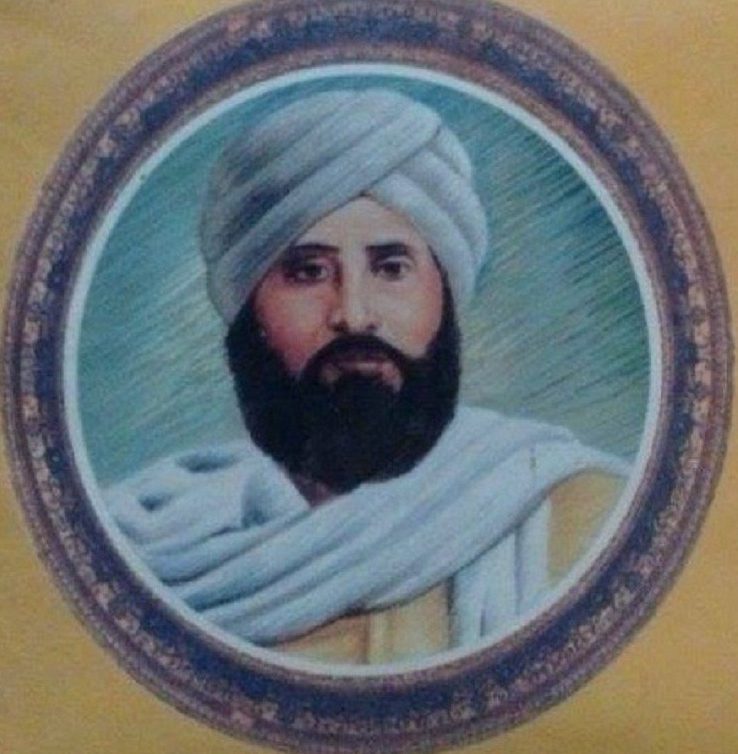

The democratic ethos of the British Raj played a significant role in freeing the Untouchables and the other backward castes from thousands of years of suppression, which culminated in the emergence of a new leadership among the untouchable communities. Swami Achhootanand was part of that leadership in northern India. He was born in 1879 in Umri village, Sirasganj, in Mainpuri district of Uttar Pradesh. His father, Moti Ram, named him Hira Lal. Soon after his son’s birth, Motiram and his younger brother Mathura Prasad joined the army. Motiram’s family thus moved to the cantonment and Hiralal received his primary education at the army school. By the age of 14, he had good command over Urdu and English.

Mathura Prasad was unmarried and used to dote on Hiralal. He was, in a way, the one who reared him. He used to recite Kabir’s verses to him, due to which Hiralal became inclined to Nirguna Bhakti during his early childhood.

Kabir’s verses had such a great impact on Hiralal that he turned into an introvert and embraced Bairaag (renunciation of worldly bondages and pleasures). Consequently, he started appreciating the Satsang (the coming together of like-minded people to engage in a spiritual dialogue) of the saints. He would welcome whosoever came to the village as a Sadhu (ascetic) and be in his noble company. Once he left home and went along with a group of Kabirpanthi sadhus and visited various places. He roamed till the age of 24, during which he gathered considerable knowledge about religion, philosophy and social conduct and also learnt Gurmukhi, Sanskrit, Bangla, Gujarati and Marathi.[2]

During those days,he met Swami Sacchidanand, a Arya Samaj preacher, and by his initiation, he became an Aryasamaji Swami. His mentor named him Hariharanand. As a follower of Arya Samaj, he studied a lot and travelled extensively.[3] But he could not be part of the institution for long. He realized that discrimination against the Untouchables prevailed there, too. According to Jigyasu, “While working for the cause of Arya Samaj, he came to know about its hollowness and became disenchanted with it. Within in a matter of days, this disenchantment turned into disgust. He discovered that Arya Samaj was a farce in the name of religion, forged to emulate Christians and Muslims with the objective to compete with them.”[4]Therefore, after serving the Samaj from 1905 until 1912, he disengaged himself. However, he remained a sadhu, and kept moving from one place to another as before. Meanwhile, his father had him marry Durgabai, daughter of Ram Singh Kuril, resident of Nagla, Rathin, in Etawah, with whom he had three daughters.

In the 1910s, leaders of Arya Samaj assured people of untouchable castes that they would work for their social upliftment, setting up schools and hostels for them and offering scholarships to the students from the “untouchable” community.

But it was just a device to keep the community within the Hindu caste system by bringing back those who had converted to Christianity and Islam. This realization made the educated Arya Samaji Untouchables break all ties with the Samaj, asserting that the people of the untouchable castes were the Adihindus (indigenous inhabitants of India). Arya Samaj had initiated a purification movement in reaction to the religious frenzy generated by Muslims on the heels of the Khilafat movement launched in opposition to the Western intervention in the Ottoman Empire. Its goal was to bring the Untouchables, who had converted to Islam, back into the fold of Hinduism by “purifying” them.[5] Soon, the untouchable Arya Samaji leaders understood the real character of the Arya Samaj. They figured that the Arya Samaj was actually a brigade ofthe upper-casteHindus, which merely intended to consolidate the Hindus against the Muslims and whose objective to uplift the Untouchables was part of that very strategy.[6]In Meerut, while exposing the Samaj, Achhootanand said:

“This is a charade in the name of Vedic religion, crafted to shield the Brahmin religion from the attacks of the Christians and Muslims. What it states is sheer bluff and its doctrines are absurd. Its idea of purification is plain deceit and what it claims to be the varna system based on virtue and works is an erroneous word trap. It is the falsifier of history, truth manipulator and an absolute windbag of false oration. Its viewpoint is flawed and expressions illogical; its establishment is flimsy and its interpretation of the Vedas is utterly concocted. It does not practise what it preaches. It aims to turn the Hindus hostile to Christians and Muslims, thus pushing them into servitude of the Vedas and Brahmins.”[7]

However, while he was with the Arya Samaj, he had deeply studied the Vedas and other scriptures and concluded that the Shudrasand Atishudras were the “Adihindus” of India.

In 1917, Achhootanand went to Delhi to attend a grand conference organized by the Untouchables. By then, he had already earned prominence as an opponent of the Arya Samaj. At the conference, Swami Akhilananda, a sermonizer of Arya Samaj, challenged him for a debate on the scriptures, which he readily accepted. The debate was held as scheduled. Akhilananda did not have a convincing answer to any of Achhootanand’s questions and ended up losing the debate. Impressed by him, Chaudhary Jankidas, Devidas and Jagat Ram, leaders from the Jatav community, proposed to rename him “Achhootanand” (literally Joy of the Untouchables). Until then, he was known by his brahmanical name, “Hariharanand”. So, Swami Achhootanand became the representative of the Untouchables of North India. He was also conferred the title of “Shree 108” for defeating the eminent scholar of the Arya Samaj.[8]

Dr Angne Lal has chronicled these events in his book Uttar Pradesh mein Dalit Andolan. However, Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu, in his treatiseAdihindu Andolan Ke Pravartak Shree 108 Swami Achhootanand Ji ‘Harihar’: Jeevani, Siddhant Aur Bhashan (1960),has stated that Swami Acchootanandwas given the appelation of “Shree 108” in 1921:

“Here, it is worth mentioning how and where Swamiji was conferred the title of ‘Shree 108’. This relates to the occasion when he went to Delhi to attend the wedding of the son of Shri Chhedi Lal Jatav, who was from Agra. There, he laid the foundation of Jati Sudhar Achhoot Sabha at Chaudhary Yadavram’s place. Following this event, with the efforts of Chaudhari Yadavram and Chhedi Lal Arya, a massive assembly was held in Chaudhary Bade’s Panchayat in front of the Red Fort. There was a stir over this gathering in Delhi. Subsequently, on 9 October 1921, a debate over the scriptures was held with poetPandit Akhilanand ji, which Swami ji won. Upon his triumph, the title of ‘Shri 108’ was bestowed on Swami ji, on the proposal of Arya preacher, Pandit Ramchandra, and the approval and consensus of Shri Naubat Singh, minister of Shahdara Samaj in Delhi, and Swami Datanand. Veerratna Shri Devidas ji, editor of ‘Pracheen Bharat’, Delhi, published this news with immense pride and joy. Thereafter, the certificate of victory was printed and widely distributed in and outside Delhi.”[9]

As part of the political reforms introduced by the British government in 1919, various religious sections of society were given representation on the basis of their numerical strength. This law was based on the Montagu-Chelmsford report, in which the untouchable sections were given minority status and a provision for their security was introduced. According to Nandini Gooptu, this law was also a major reason behind the Shuddhi(reconversion) movement of the Arya Samaj aimed at increasing the Hindu population.”[10] On the other hand, this law paved the way for the political rights of the untouchable sections of society. Dr Ambedkar has written that it was unfortunate that while the particulars of the Government of India Act 1919 were being framed, the government found it difficult to make any provision for the protection of the untouchable sections, except their nominal representation in the legislative assemblies through nomination. In such a situation, first of all, it was imperative that Untouchables asked for necessary measures for their security in the face of the atrocities and oppression by the Hindus. Dr Ambedkar ensured that this was done when he submitted a memorandum to the Minorities Committee in the Round Table Conference. The memorandum consisted of eight demands, among which equal citizenship rights, freedom to exercise equal rights, protection against discrimination, adequate representation in legislatures, adequate representation in government services, redress against prejudicial action or neglect of interests, were prominent.[11]

In 1921, two years after the 1919 Act came into force, Edward, Prince of Wales, came to India. Though the Congress boycotted him, a large number of Untouchables welcomed him on 22 November 1921 in Bombay and 14 February 1922 in Delhi. A huge All India Achhoot Conference was held in Delhi under the leadership of Swami Achhootanand in which thousands belonging to untouchable sections across the country participated. Prince Edward was welcomed at this conference and presented with a 17-point charter of demands. Katherine Mayo has described the spectacular event in her book Mother India. She says 25,000 Untouchables welcomed the prince.[12] According to Jigyasu, there were “lakhs” of them. His version is as follows:

“In 1922, after the Non-Cooperation Movement, the Prince of Wales came to India, where the Congress leaders boycotted him. At the time, Swamiji was in Delhi. The boycott did not appeal to him. On this occasion, he held a massive gathering of the Untouchables in Delhi and declared, ‘My brothers! We are the ancient inhabitants, the Adihindus of India. The Aryan Dwijs are all outlanders. They have enslaved us by branding us as servile and untouchable. We need to step out of the delusion spread by these people and independently fight for all our civil rights. We should not rebel against the British government; rather we should welcome the princeand ask for our political rights from the British government.’ Needless to say, this had a magical effect on the Untouchables. Lakhs of them gave the prince a lofty welcome and the term ‘Adihindu’ echoed in the ears of the people.”[13]

It was at this conference that Swami Achhootanand founded the Adihindu Sabha in Delhi. Its principles were as follows: participation of Untouchables and other backward castes in the Adihindu movement, promotion of interdining, faith in the tradition of Nirguna saints, revolutionary struggle against inequality, truth as the only means to attain divinity, and one’s own effort as the only way to enlightenment.[14]

Jigyasu writes that after this gathering, the term “Adihindu” was heard not only across the country but also in British Parliament in London. Numerous conferences, assemblies and meetings were convened at various places on the “Adihindu” identity. In 1930, the eighth session of the All India Adihindu Conference was held in Allahabad, during which it was reported that by then a total of 11 All India Adihindu Conferences had already been held in Delhi, Bombay, Hyderabad, Nagpur, Allahabad, Madras, Amravati and Meerut. Similarly, 15 provincial conferences had been held – in Kanpur, Lucknow, Allahabad, Meerut, Mainpuri, Mathura, Etawah, Gorakhpur, Farrukhabad and Agra among others. Jigyasu further notes that 208 district-level Adihindu Sabhas had been held until November 1930. However, no data pertaining to national, provincial and district-level Adihindu Sabhas held is available from the period that followed.[15]

According to Jigyasu, the Adihindu movement was not limited solely to British India (the states under British government) but also spread to countless princely states, such as Gwalior, Bhopal, Jaipur, Alwar, Hyderabad, Bharatpur and Tehri Garhwal through numerous gatherings.[16]

Jigyasu has made a significant observation: “From anideological perspective, the Adihindu movement is genuine socialism, and Swami Achhootanand and Babasaheb Ambedkar are Karl Marx and Lenin of India. The Adihindus are the proletariat of India and Dwij Hindus and their supporters, the Indian bourgeois.”[17]

Asthe Adihindu movement spread all over, and every district started hosting a meeting, the haughty upper-caste Hindus, especially Aryasamajis, began to make allegations against Swami Achhootanand and spread rumours to tarnish his image. According to Jigyasu, somebody alleged Achhootanand was a Christian who was on the payroll of Christians and would get everyone converted. Others claimed that he was working for the Muslims and still others called him a British stooge. Gossipers would say that he was excluded from Arya Samaj due to his immorality and since then he had been criticizing it. This false propaganda scared many Untouchables away and they too did not come to Achhootanand’s support. But despite this, Achhootanand did not give up. According to Jigyasu: “He would sleep sometimes without having a meal and sometimes after chewing on grams. He would traverse miles on foot because he didn’t have any money. Yet, he would not be distracted from his goal and principles. He was firm on his mission. Through his preaching, he awakened the unconscious, uplifted the fallen and revived the inert community.”[18]

When intimidation and spurious propaganda fail to distract a movement, a conspiracy to infiltrate it and capture its leadership follows. The movement is thus annihilated or distorted from within. Buddhism, Jainism and the philosophies of saints like Kabir and Raidas were distorted in the same manner. Ajivak Dharma was erased. Upper castes attempted to appropriate the leadership of the Adihindu movement, but they were not successful. That is why Achhootanand did not allow anyone from the upper castes to even preside over the meetings of the Sabha. Jigyasu relates this incident:

“No ruler, king or aristocrat could buy Swami ji off. One instance of his boldness is always cited. In the course of propagating the principles of Adihindu movement, he went to India’s ancient capital, Kannauj. It was decided to hold a huge gathering of the Untouchables there. The king of Tirwa helped immensely in setting up the tent and the stage. The venue was well decorated. Some Untouchables thus thought of asking the king to chair the meeting. Many giddy, coward and smooth-tongued Untouchables even went to invite the king. However, when Swami ji came to know about it, he fearlessly disapproved of it. He clearly said that the meeting of Untouchables cannot be chaired by a king and that it should be chaired only by a deserving Untouchable. Consequently, the king wasn’t made the chairperson; Mahatma Ramcharan Kuril, an untouchable leader, was. This was a brilliant example of Swami ji’s ancestral pride and fearlessness.”[19]

On 28 April 1930, Achhootanand revealed at a conference of Adihindu Samajik Parishad in Amravati, Barar, that the Hindus had threatened to kill him. The news was published in Arjun newspaper, dated 13-14 July 1927.[20] He had already been attacked in Agra but he had managed to escape unhurt. These attacks and protests proved that Achhootanand was not following the path laid down by the Hindus, rather he was refuting their religious system. The second reason was that Achhootanand had turned the Adihindu movement from a social movement into a political movement. Had he restricted himself to social work, the Congress supporters and Aryasamajis wouldn’t have held any grudge against him. But the political atmosphere was not in favour of the Untouchables. The Swaraj movement of the Congress was talking only about Hindus; there was no mention of liberation of the Untouchables. Against this backdrop, it was imperative for the Adihindu movement to be political. Parallel to the Swaraj movement, Dr Ambedkar was already leading the movement for the emancipation of Untouchables. At the Adihindu Conference held in Bombay in 1928 both leaders met face to face for the first time. However, they were both acquainted with each other’s endeavours and struggles. After a discussion with Dr Ambedkar, Achhootanand got an inclination for politics, and there itself, he decided to extend full support to Dr Ambedkar’s mukti-sangram (war for freedom). It was the need of the hour, as Dr Ambedkar had said “if not now, then never”. That was the appropriate time when the British government could be pushed to take measures for liberating the Untouchables. Letting that opportunity go would mean leaving the Untouchables in their deprived state, inferior to the Hindus.

Prior to the launch of the Adihindu Sabha, Achhootanand had already submitted a memorandum to Prince Edward regarding liberation of Untouchables, during his welcome in Delhi in 1922. Still, on behalf of the Sabha, Achhootanand, accompanied by thousands of people, welcomed the members of the Simon Commission with great pomp on their arrival at Charbagh, Lucknow, on 29-30 September 1928. He also submitted the charter of demands for political rights, while the Congress leaders had opposed and boycotted the commission. According to Dr Angne Lal, Bhadant Bodhanand played the most significant role in organizing the event to welcome the commission.[21]

It was then only that Congress leader Lala Lajpat Rai prepped Chaudhary Bihari Lal, a Harijan leader of Uttar Pradesh, to counter Achhootanand. Bihari Lal used to obstructAchhootanand’s meetings, spread false propaganda against him and denigrate him.[22]

This was the period when two claimants of political power were emerging – Qaid-i-Azam Jinnah and Mahatma Gandhi. While Jinnah represented the Muslims, Gandhi stood for the Hindus. Gandhi assumed that the backward classes, including the Untouchables, were part of the Hindu community. At the same time, Dr Ambedkar declared that the Untouchables were non-Hindus and therefore a minority section and demanded separate representation. This proved to be detrimental to Gandhi’s tactics. Dr Ambedkar firmly advocated the cause of Untouchables and attended the Round Table Conference held in London to demand a separate electorate for them. With his strong arguments, he dismissed Gandhi’s leadership of the Untouchables. The Congress and leaders of the Arya Samaj conspired in every possible way to quash Dr Ambedkar’s claims. They even sent fake letters to London on behalf of the Untouchables stating that Gandhi, not Ambedkar, was their leader. Nevertheless,Achhootanand did not allow their trick to succeed. He consistently defied Gandhi and Congress in the Adihindu meetings and backed Dr Ambedkar. To counter the fake letters, he forwarded numerous genuine letters to London on behalf of the Untouchables in opposition to Gandhi and in support of Ambedkar. As a result, Dr Ambedkar’s claim received full endorsement and British Prime Minister conceded the demand for a separate electorate for Untouchables in the “Communal Award”. But Gandhi sat on a fast unto death in his protest against this decision and Dr Ambedkar had to lose the battle already won.

Dr Ambedkar and Gandhi signed an agreement in Pune, agreeing on a joint electorate for reserved constituencies for Untouchables. Dr Ambedkar was forced to arrive at a compromise, for the Hindus were powerful and would have otherwise inflicted violence upon Untouchables in villages and cities, since for the Aryans, violence in the name of religion was justified. Jigyasu writes that when the Poona Pact was being arrived at, Swami ji was ill. He thus could not contribute much in this matter. Later, when people asked his opinion on the agreement, he laughingly said in a weighty tone, “whatever happened was good enough. Now accepting it is the wise thing to do. On one hand, it saved Mahatma Gandhi’s life and we escaped the blot. On the other hand, we have maintained our amity with the elder brothers (Hindus). Now, let us see how the Hindus atone for their wrongs and perform self-purification. But this agreement does not mean that our social and religious movement will come to a halt. It should rather be carried out more vigorously now. We do not need to enter the Hindu temples. The entire world and every heart is a temple of our self-god. Whatever has happened is all due to our Adihindu movement.”[23]

Saddened and embarrassed by the revelations in the Round Table Conference in London about the inhuman atrocities committed by the Hindus upon the Untouchables, Gandhi, on his return to India, named the Untouchables as “Harijan”.According to Jigyasu, Gandhi changed the name of his newspaper from Navjivan to Harijan Sevak. Moreover, Harijan Sevak Sangh was founded only because he wished it.[24]Even the Hindu press started using the name “Harijan”. But Swami Achhootanand disliked this term. He composed an impressive bhajan to express his discontent. It is part of the collection Swami Achhootanand Rachna Sanchayita. In the bhajan, he said: “After ‘Antyaj’, ‘Patit’, ‘Bahishkrit’, ‘Padaj’, ‘Pancham’, ‘Sankar’, ‘Varnadham’ and ‘Achhoot’, Gandhi has now given us the status of ‘Harijan’. ‘Hari’ means ‘God’ and ‘jan’ means ‘man’. Therefore, ‘Harijan’ or ‘Khuda-e-jan’ means someone whose parents are unknown. If we are Harijans, then how come you are not? Does it mean that you are the offspring of the devil?” In other words,

Kiyo harijan pad humein pradaan

Antyaj, patit, bahishkrit, padaj, pancham, shudra mahan.

Sankar baran aur varnadham pad achhoot upmaan.

Hari ko arth khuda, jan banda jaanat sakal jahan.

Bande khuda n baap-maai ka jinke pata thikan.

Hum Harijan toh tum hun harijan kas na, kaho shriman?

Ki tum ho unke jan, jinko jagat kahat shaitan?[25]

Achhootanand was not only the progenitor of the Adihindu movement and an astute political orator, but also the founding father of Hindi Dalit literature and journalism. He published the Pracheen Hindu magazine Delhi for two years between 1922-23 and from 1924 to 1932, he brought out theAdihindu magazine from Kanpur, where he had also set up a printing press by the name ‘Adihindu’ in 1925. He was the first Hindi Dalit poet. In his poetry, we find the evolution of Kabir and Raidas’Nirgun ideology. He used to publish his poetry under his pen name “Harihar”. His work of poetry, Adi Khand Kavya, is quite significant. H.L. Jatiya, municipal commissioner and Kannauj Adihindu Sabha chief, published it on 13 May 1929. On its front page, it is written, “With the satisfaction of finally retrieving this extraordinary long lost work of poetry ofShree 108 Achhoot Swami ji Maharaj, it is dedicated to the Adihindu (Shudras, Achhoot) brothers.”[26]

This is confirmation that Adi Khand Kavya dates back to several years before 1929, when it was eventually published. Composed in Alha tune, this is a poem of 63 verses and eight lines. Its last lines carry the message of organizing both the Untouchables and the other backward castes:

Jo azad hon tum chaho, toh ab chant dewu sab chhoot.

Adivansh mil jor lagao, pandrah koti sachhoot-achhoot.[27]

The collection of his poems, ghazals and bhajans, Adivansh Ka Danka, was published only once in Achhootanand’s lifetime (1913-1914). Later, it was again published by Bahujan Kalyan Prakashan in Lucknow – fifth edition in 1960 and eleventh in 1983, which is an indication of its popularity. His popular poem Manusmriti Se Jalan, is part of this collection, probably the first Dalit poem on Manuvism. Composed in Qawwali tune, its each line is quite suggestive:

Nishdin Manusmriti ye humko jala rahi hai.

Oopar na uthne deti, niche gira rahi hai.

Brahman wa Kshatriyon ko sabka banaya afsar.

Humko purana utaran pehno, bata rahi hai.

Humko bina mazoori, bailon ke sath joten,

Gali aur maar uspar, humko dila rahi hai.

Lete begaar, khana tak pet bhar na dete,

Bacche tadapte bhookhe, kya zulm dha rahi hai.

Eh Hindu kaum sun le, tera bhala na hoga,

Hum bekason ko ‘Harihar’ gar tu rula rahi hai.[28]

Achhootanand initiated the tradition of playwriting in Dalit literature. Two of his available plays are Mayanand Balidan and Ramrajya Nyaya. However, according to Chandrika PrasadJigyasu, “Swamiji had many plots in mind, through which he wanted to disseminate knowledge about ‘Adihindu’. But he was so busy and taken up that he did not have enough time put pen to paper. The plays that left a lasting impression were Samudra Manthan, Bali Chhalan, Eklavya and Sudas and Devdas.”

While introducing them, Jigyasu writes, “The theme of Samudra Manthan revolves around the trickery and guile of the Arya deities and the Adivasi Asuras being deceived by Vishnu in the garb of a seductive woman. Bali Chhalan depicts Vishnu’s incarnation as a dwarf, a conspiracy hatched by the Arya deities and Brahmins to betray the utmost generous and valiant Adivasi, Asur emperor, Bali. Eklavya narrates the story of the matchless archer and the son of a Nishad (a lowly caste). Eklavya was ignobly asked to severe his thumb. Sudas and Devdas aimed at demonstrating that both, Sudas and Devdas, were Adivasi kings. Like Vibhishan and Jayachand, Devdas joined hands with Indra, the commander of the Aryans who conspired against Sudas. As a result, Sudas was defeated and Aryans were able to exercise control over Sindh and Punjab region.”[29]

Mayanand Balidan is a play written like a Kanpuri song. The genre features the songs of Shrikrishna Pehelwan with verses that take the form of Doha, Chobola, Daud, Baharatbeel and Gazal. This play was published in July 1926 by the Adihindu All India Mahasabha, Kanpur. A line by Kabir, “Kahen kabir te chhoot vivarjit jaake sang na maaya” is given a the top of the cover page. Below the line is the name of the play followed by the following line: “Adihindu sadhu ko naramedh yagya mein bali dena.” Then there is this introduction: “Itihaas ki is sachchee praamanik ghatana ko hazaar varsh beete is mahaatma ne Adihindu jati par jaan dekar nagar mein basne, pahanne aur odhne ki azadi dilayi thi.” (This historical incident took place a thousand years ago, when this mahatma secured the freedom to settle in the city and wear and drape for the Adihindujati by sacrificing his life). The play is centred on Patan city (Gujarat region) under Siddharaj rule where a dam was being built on the sea in 11th century Vikram Samvat to put an end to the shortage of water but in vain. When the king asked the Brahmins for a remedy, they advised him to perform Narmedh Yagya. The Brahmins caught hold of an anti-Vedic Untouchable, Mayanand, and took him to the king for sacrifice. Before offering himself for sacrifice, Mayanand told the king that he would do so if a decree was issued to give the Untouchables the right to settle in the city, wear and drape with freedom. The play says that the king fulfilled the wish of Mayanand and immediately issued the decree.[30]

The play Ram Rajya Nyaya depicts the slaying of the Shudra rishi, Shambuk, by King Ram. This composition is surely from before 1927. Achhootanand’s poem Manusmriti, which is a part of this play, is a soliloquy by Shambuk. This play is not available in its original form. Jigyasu published an abridged version, adding songs to it under the pen name ‘Prakash’.[31]This play remained unpublished for 14 years before it was published for the second time in 1964. In 1995, its eleventh edition was published.[32]

Although Achhootanand enjoyed a lot of success, he lacked wealth and wasn’t blessed with sound health. His health deteriorated since he was always working. He never stopped travelling on foot. He always carried a bag in which he kept all the necessary items for running the office of AdihinduSabha. While travelling, he used to write whenever he got time. He composed most of his literary works during his travels. His health worsened after the Virat AdihinduConference held in Gwalior in 1932. He could not afford proper treatment. His treatment by quacks proved fatal. His health deteriorated further and he passed away in Zhabar Idgah, Kanpur, on 20 July 1933 at 9.29 am at a relatively young age of 54 years. The sun that awakened the aspiration for freedom among the Untouchables and other backward castes in north India had set forever.

Jigyasu wrote:

ek aala dimaag tha, na raha.

adivanshee chirag tha, na raha.

After Achhootanand’s demise, the Adihindumovement, in a way, collapsed. While some of its members joined the Congress in search of better prospects, others remained loyal to the movement and merged with Babasaheb Ambedkar’s Scheduled Caste Federation.

Translation: Devina Auchoybur; copy-editing: Anil

References:

[1] Indian history has witnessed three such noteworthy periods: Buddha’s era, Muslim era and British era

[2]Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, ed Kanwal Bharti,The Marginalised Publication, Delhi, 2017, p 346

[3]Uttar Pradesh mein Dalit Andolan, Dr Angne Lal, Gautam Book Centre, Shahdara, Delhi, 2011, p 22

[4]Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, ed Kanwal Bharti,The Marginalised Publication, Delhi, 2017, p 346

[5]Swami Achutanand & the Adihindu Movement, Nandini Guptoo, Critical Quest, New Delhi, 2006, p 12

[6] ibid, p 13

[7]Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, p 347

[8] Dr Angne Lal, Uttar Pradesh mein Dalit Andolan, ed Rahul Raj, Gautam Book Centre, Shahdara, Delhi, 2011, p 23

[9]Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, p 351

[10]Swami Achutanand & the Adihindu Movement, Nandini Guptoo, Critical Quest, New Delhi, 2006, p 13

[11]Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches, Volume 9, ‘What Congress and Gandhi have Done to the Untouchables’, Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, Bombay, 1990, p 40-52

[12]‘Such was their enthusiasm; many among them had come from Delhi. It was a crowd of twenty five thousand untouchables that awaited the arrival Prince. A huge gathering had come from all sides to see him’ (Katherine Mayo, Mother India, Hindi Translation: Kanwal Bharti, Forward Press, New Delhi, 2019, p 155)

[13]Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, p 348

[14]Dr Angne Lal, ibid, p 22

[15]Chandrikaprasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, p 357

[16]ibid, pp 357-358

[17]ibid, pp 359

[18]ibid, p 49

[19]ibid, pp 349-350

[20]ibid, pp 349-350

[21] Dr Angne Lal, ibid, pp 26-27

[22]Swami Achhootanand ‘Harihar’ aur Hindi Navjagaran, Kanwal Bharti, Swaraj Prakashan, New Delhi, 2011, pp 269-277

[23] Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu Granthavali, Part 2, Ibid, p 357

[24] ibid, p 423

[25] Swami Achhootanand Harihar Sanchita, Compilation: Kanwal Bharti, Swaraj Prakashan, New Delhi, 2011, p 139

[26] ibid, p 112

[27] ibid, p 120

[28] ibid, p128

[29] ibid, pp 39-40

[30] ibid, pp 63-78

[31] ibid, p 82

[32]Swami Achhootanand ‘Harihar’ aur Hindi Navjagaran, Kanwal Bharti, Swaraj Prakashan, New Delhi, 2011, p 255

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen