Guru Ghasidas Birth Anniversary Special (18 December 1756 – 1836)

Construct of ‘untouchable’ identity

In Chhattisgarh, the construct of the Satnam identity has a long-standing backdrop – factors and conditions such as blatant untouchability practices, from deprivation to frustration (Gurr 1970: 7), exclusion, as well as the feudal system that defined relationships and landholding. Deprivation leads people to frustration and the greater the frustration, the greater the degree of aggression against the sources of frustration. The social sharing of deprivation is therefore the starting point of protest. Louis (2003: 126) points out that identity formation is based on the experience about oneself, experience in relation to others who are different from oneself. In this regard it can be stated that identity formation is an interactional process.

Franco (2002: 16) argues on two inter-related components in identity formation. The first is the ideological-symbolic one. This refers to the system of beliefs and practices that flow from the understanding of the position of oneself and one’s own group vis-à-vis others. This set of beliefs and its various cultural expressions provide the group with a shared meaning and understanding about who they are and what their role is in a given social context. The second is the material-productive component. It refers to material, ecological and economic conditions shaping and determining the primary livelihood activities of the group that in turn determine production relations.

Those removing human waste and skin animal carcasses, tanning leather, making shoes, washing clothes and providing other essential services mostly lived outside the village. They were not only restricted in terms of space but also with regard to amenities – their houses had to be inferior in quality and devoid of any facilities (George: 2013). Thus, the numerous pollution-related taboos pushed them to the lowest rungs of society.

Ambedkar investigated the historical origin and various other aspects of identity.

“One set of facts comprise the names Antya, Antyaja and Antyavas given to certain communities by the Hindu Shastras. They have come down from very ancient past. Why were these names used to indicate a certain class of people? There seem to be some meaning behind these terms. The words are undoubtedly derivative. They are derived from the root Anta. What does the word Anta mean? …Shastras argue that it means one who is born last and as the Untouchable according to the Hindu order of Divine creation is held to be born last, the word Antya means an Untouchable. The argument is absurd and does not accord with the Hindu theory of the order of creation.

According to it, it is the Shudra who is born last. The Untouchable is outside the scheme of creation. The Shudra is Savarna. As against him the Untouchable is Avarna, i.e., outside the Varna system. The Hindu theory of priority in creation does not and cannot apply to the Untouchable. In my view, the word Antya means not end of creation but end of the village. It is a name given to those people who lived on the outskirts of the village. The word Antya has, therefore, a survival value. It tells us that there was a time when some people lived inside the village and some lived outside the village and that those who lived outside the village, i.e. on the Antya of the village, were called Antyaja” (Ambedkar Vol 7, 1990: 278-279).

From ‘untouchable’ identity to Satnamis

The caste system, untouchability and the Untouchables in Chhattisgarh and the negotiation for a new identity needs to be looked at within this context. Notable among these negotiations is the Satnami movement. The formation of a new sect or conversion to another religion has been one of the oldest movements towards the creation of a new identity. Undoubtedly, brahmanical caste rigidity and tyranny led Dalits to quit Hinduism (George 2006: 34).

Conversion as a phenomenon, leading to a change of faith, has been one of the principal means through which social promotion has been sought in India for ages (Lobo 1996: 167-168). All sects within Hinduism that proclaimed equality attracted a large number of people. For instance, after the 13th century, the Bhakti movement spread all over India through charismatic persons like Kabir, Ravidas, Chaitanya, Eknath, Chokamela, Tukaram, Narsinh Mehta, Ramanuja, Basav and Nimbark. They preached equality, which the Untouchables longed for intensely.

Islam found favour for the same reason. It gave a new hope of equality and an economic space for growth to the historically oppressed strata. The mass conversions to Islam, Sikhism and Christianity threatened upper-caste dominion. This is the context under which the emergence of a new identity under Satnampanth attains immense importance.

According to Dube (2001:1), “in the early nineteenth century, around 1820 a farm servant named Ghasidas initiated a new sect primarily among the Chamars (traditionally leather workers) of Chhattisgarh. Ghasidas was born into a family of Chamar farm servants in the late eighteenth century possibly in the 1770s in Girod in the northeast of the Raipur [presently Balodabazar] district. This new sect was called Satnampanth and its members Satnamis.”

The formation of Satnampanth in the early 19th century helped forge a new identity for the Antyajas of Chhattisgarh. The late 18th and early 19th centuries were a period of change in the region. Cultivation expanded, the revenue demands of the State increased and a Brahmin-dominated bureaucracy replaced the older structures of authority. Dube (2001:25) writes that the various administrative measures of the Marathas and British had contradictory economic and cultural consequences for the Chamars of Chhattisgarh. The Satnampanth at once drew upon popular traditions and rejected the hierarchy of ritualistic purity and pollution, the “divinely ordained” and social hierarchies that centred on the Hindu pantheon, and repositioned traditional symbols in a new matrix. It questioned and challenged the ascribed status of Chamars as low Untouchables, as those polluted by their handling of the carcass of the sacred cow. The Chamars who joined the sect were cleansed of their impurity and marks of ritual subordination, and reconstituted as Satnamis.

Creation of a sect like Satnami signified an overriding rejection of the religious code of Manu and the proposition of an alternative faith for themselves. It essentially embodied refusal of Brahmanism, which was perceived to be the root cause for their sufferings. The most articulate expression of this refusal in Chhattisgarh is the Satnam movement’s overthrowing of Hindu religious ideological hegemony as a necessary condition for the liberation of Dalits (George 2013).

The tyranny and oppression that the Chamars underwent even after becoming Satnamis under the guruship of Ghasidas needs critical study. Dube (2001: 55) quotes Oscar Lohr’s account to describe the problems faced by Satnamis in these words. “The low ritual status of the community meant that there were marked restrictions on clothes, ornaments and accessories. Satnami men were not expected to wear a full-size dhoti and don a turban or appear in shoes before upper castes. Satnami women were denied a saree with a coloured border and were not allowed silver or gold ornaments. An umbrella, fashioned as a distinctive cover of authority – arguably through a refiguring of the meanings of the Chhattra (ornamental canopy) of rajas and gods that at once signified the divine attributes of royalty and the regal aspects of divinity – was reserved for use by upper caste order. It was in keeping with these cultural schemes that the Satnamis were forbidden from riding horses and elephants and using a palanquin during their weddings.”

Satnam revolution of Guru Ghasidas

Ghasidas was born on 18 December 1756 in Girodpuri village of the present Balodabazar district. He was the son of Mahngu Das and Amrotin Devi. He founded the Satnampanth (path of truth) particularly for the Dalit people of Chhattisgarh. Ghasidas experienced the evils of the caste system at an early age, which opened his eyes to the social dynamics in a caste-ridden society and led him to reject social inequality. He travelled extensively across Chhattisgarh to look for ways to do away with this inequality. Guru Ghasidas created a symbol of truth called “jaitkhambh” – a white painted log of wood, with a white flag on the top. The log of wood is meant to be the pillar of truth (satya ka stambh) for anyone who follows the truth, “satnam”, and the white flag symbolizes peace.

Guru Ghasidas is the founder of the anti-caste revolution in Chhattisgarh. Chisholm (1869: 46-47) notes that Satnampanth drew inspiration from Kabirpanth. Ghasidas became the guru of the new sect. The guru forbade his disciples to worship idols, instructed them to believe only in Satnam, who is the formless maker of the universe, and to follow a code of social equality. Satnampanth turned its members into Satnamis. It was almost exclusive to the Chamars of Chhattisgarh, apart from a few from other socially backward groups.

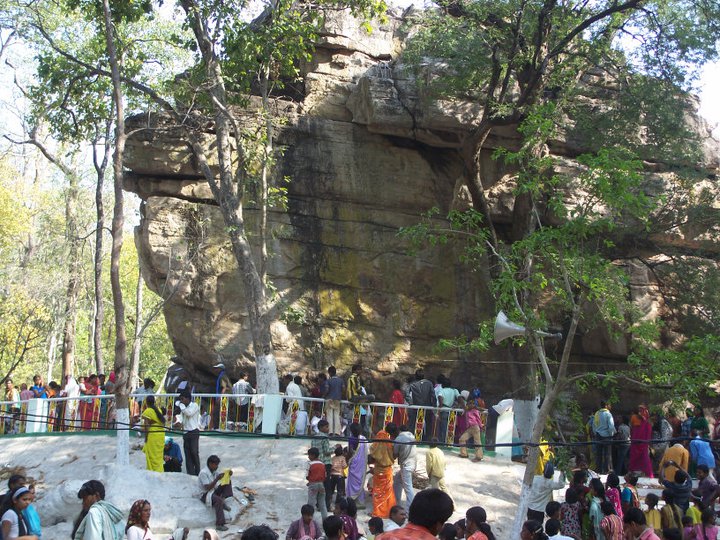

It was during his travels through Chhattisgarh that once when he was on his way to Puri, he abandoned pilgrimage and began an ascetic life. He meditated in the jungles of Sarangarh, where he attained the enlightenment of “Satnam”. From that time onwards, he would retire to the forest regularly for meditation. On a rocky hillock about a mile from his native village there is a large tendu tree under which it is said that he would often sit and meditate. This is still a site of pilgrimage of the Satnamis marked by two Satnami temples.

Ghasidas gave his followers a seven-fold path for the betterment of humanity, which includes faith in truth (satnam), prohibition of idol worship, forbidding the varna system, abstinence from violence, refraining from (alcohol) addiction, banishing of adultery and not ploughing the field in the afternoon to give rest to cattle. Right from his childhood he was against the inhuman system of caste, untouchability and animal sacrifice. These teachings of the guru instilled a new level of confidence among the oppressed masses, a new identity and a new spirit to fight oppression and injustice (George 2013).

Russell and Hiralal (1916: 406) note that Satnamis were forbidden meat, alcohol, tobacco and some specific vegetables and pulses. They were instructed not to plough after the midday meal so that the cattle could rest. They kept their distance from a major section of Chamars known as the Kanaujia Chamars. The Kanaujias did not join Satnampanth and retained their own separate identity.

Based on testimonies, oral tradition on Ghasidas and speculative history, Chisholm (1869) says that the movement then was not more than fifty years old and probably started between 1820 and 1830. Ghasidas and his movement quickly gained popularity. People from far-away places would visit him, touch his feet in reverence and make offerings.

Lohr, as Dube (2001: 55) quotes him, was struck by the prohibitions imposed on the Satnamis in the public space on account of their collective embodiment of the stigma of extreme pollution. The community was denied the services of the barber and the washerman. The group was also not permitted to participate in melas (fairs) and could not enter temples and the interior of public buildings. The Satnamis were not allowed to get too close to a provision store and therefore could not examine merchandise before buying it. Finally, the institution of begari (unpaid labour rendered by tenants to their malguzars) led to the use of force by village proprietors, particularly during seasons when Satnamis’ own fields needed attention. Landless Satnamis, on the other hand, were kept as serfs. They were not paid any wages and often worked for just food and clothes.

It was during this phase of history when the Chamars needed transformation, they responded to the call of Ghasidas positively. Ghasidas challenged both the caste system and the colonial authority. He was time and again threatened and survived several attacks prompted by the upper castes. The fast-progressing organizational and institutional life of Chamars in the form of Satnami was not acceptable to the dominant castes. Ghasidas died at the age of 80. At the time of his death the Satnampanth had approximately 250,000 members and the teachings of Ghasidas continued to inspire them (Russell and Hiralal 1916: 47).

Briggs (1920: 27) terms the Satnampanth started by Ghasidas as a new emergence, differentiating it from the earlier Satnam formations that trace their origin to Kabir or to his teachings and influence (ibid: 205). The Satnampanth movement in Chhattisgarh is of considerable importance as a socio-cultural revolt of the Dalits. As a struggle for socio-economic mobility, it has succeeded largely, despite all the attempts to nullify it.

Yet, despite leaving behind leatherwork, Satnamis continued to be treated as Untouchables. While the anti-caste Satnampanth became stronger, the upper castes oversaw the consolidation of brahmanical caste order. There are still a lot of historical aspects to be explored particularly in the context of the creation of a sect like Satnampanth. In the later phase, the Satnam movement underwent various phases of ups and downs.

Challenges before the Satnam movement today

Undoubtedly the Satnam movement made a huge impact on the Untouchables in the 19th century. At present, many complications have cropped up and the movement has lost its intensity. There is a need for the movement to reinvent and reinvigorate itself at a time when there are several Constitutional provisions and laws at its disposal to fight casteism.

If one analyzes the series of atrocities over the last couple of decades, we find that most of the victims have been from the Satnami community, particularly in rural Chhattisgarh. The response of the community has been cold. There has been hardly any consistent effort to seek redress under Indian Constitution, Protection of Civil Rights Act 1955, SC &ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989 and other laws. In fact, there are many international laws, covenants and conventions to which India has been a signatory. Being a signatory means that the State is obliged to fully implement what has been agreed upon. Even if the affirmative rights of Dalits pertaining to education, healthcare, reservation and social security exist on paper, these rights are often denied to the Dalits in practice, adding to the list of violations of their rights.

The persistence of caste as the most powerful institution in the making of modern India is the biggest threat to its democratic fabric. The situation in Chhattisgarh is critical, because it has also developed into the larger laboratory of neo-liberal experimentation. Attacks on Dalit settlements, land acquisition by corporate capitalists and psychological manipulation through Hinduization or Sanskritization of Dalits and Dalit movements have been the end product. The Satnamis today are therefore not only the victims of caste-based atrocities and discrimination but also of attempts to culturally and economically annihilate them.

Conclusion

Dalits across the Chhattisgarh live in a state of fear. The dominant castes have succeeded in instilling the fear that anyone who would try to break the shackles of caste would be defeated. This social system has been assimilated into the political, administrative and psychological frameworks. Satnamis, too, don’t seem to be making an attempt to break these shackles. This completes the hypothesis of social power and its relationship with the process of oppression.

Today, Chhattisgarh is faced with the threat of a new form of slavery with the consolidation of caste politics. In the name of delimitation, the number of reserved seats has been reduced. Reservation in education and employment has been also under severe threat due to the policies of both the central and state governments. Reinvention of new formats of casteism has been already seen in the state. For instance, over the past two decades, several cases were brought to the light by Dalit groups where the Dalit Sarpanches were not allowed to function in a free and fair atmosphere. Scores of instances of discrimination in schools by teachers have come to light. The question is, what is the way out?

The movement for equality created by Guru Ghasidas is under severe threat. He rejected the Hindu theories of creation and the Supreme Being. He stood for “True Name” alone, the one God, the cause and creator all things, the Nirguna. The sect had no visible symbol or representation of the Supreme Being. Today, Satnamis have gone against his teachings and practice idolatry. They also pay no heed to Ghasidas’ stand against temples, public religious service, creed and “bhakti”. Ghasidas’ movement thus stands at the crossroads today.

Undoubtedly the 200-year-old Satnam movement has instilled a strong sense of pride, self-respect and spirit of self-determination among the historically oppressed sections of society. However, the question today is: Are Satnamis free of the brahmanical social order? Have they not merged Guru Ghasidas’s movement with the Hindu system of domination? Are the Satnamis today free from caste? Does the Satnampanth stand on the foundation of anti-caste movements such as justice, equality, liberty and fraternity? These questions need answers today.

References

B.R. Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches (1990), Vol. 7, Education Department, Govt. of Maharastra, Mumbai.

Briggs, G.W. (1920), The Chamars, Oxford University Press, London.

Chisholm J. W. (1869), Report on the Land Revenue Settlement of the Belaspore District, 1868, Nagpur.

Dube, Saurabh (2001), Untouchable Pasts: Religion, Identity, and Power among a Central Indian Community, 1780-1950, Vistaar Publication, New Delhi.

Franco, Fernando (2002), Pain and Awakening: The Dynamics of Dalit Identity in Bihar, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, Indian Social Institute, New Delhi.

George, Goldy M. (2006), ‘The Future of Dalit Movement in India’, theme paper in the National Seminar on “How can we ‘Survive’ and ‘Succeed’ Ambedkarism in the 21st century?” from 18-21 November, Nagpur.

George, Goldy M. (2013), ‘Dalit & Tribal Social Work: Theorising Indigenous Paradigms of Intervention from Central India’. Keynote presentation in the National Conference on ‘From Traditional to Dalit & Tribal Social Work – Indigenous Social Work in India Today’ organised by Centre for Social Justice and Governance, Tata Institute of Social Work, in collaboration with Dalit & Tribal Social Work International Collective at TISS Campus Mumbai between 20-22 April, 2013.

Gurr, T. R. (1970), Why Men Rebel?, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Lobo, Lancy (1996), ‘Dalit Religious Movements and Dalit Identity’, in Walter Fernandes edited The Emerging Dalit Identity: The Re-assertion of the Subalterns, Indian Social Institute, New Delhi.

Louis, Prakash (2003) Political Sociology of Dalit Assertion, Gyan Publishing House, New Delhi.

Russell R. V. and R. B. Hiralal (1916) The Castes and Tribes of Central Provinces of India, 4 Vols. Macmillan, London.

Copy-editing: Anil

(Article has been slightly re-edtied on 19th Dec, 2019 4:50 PM)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)