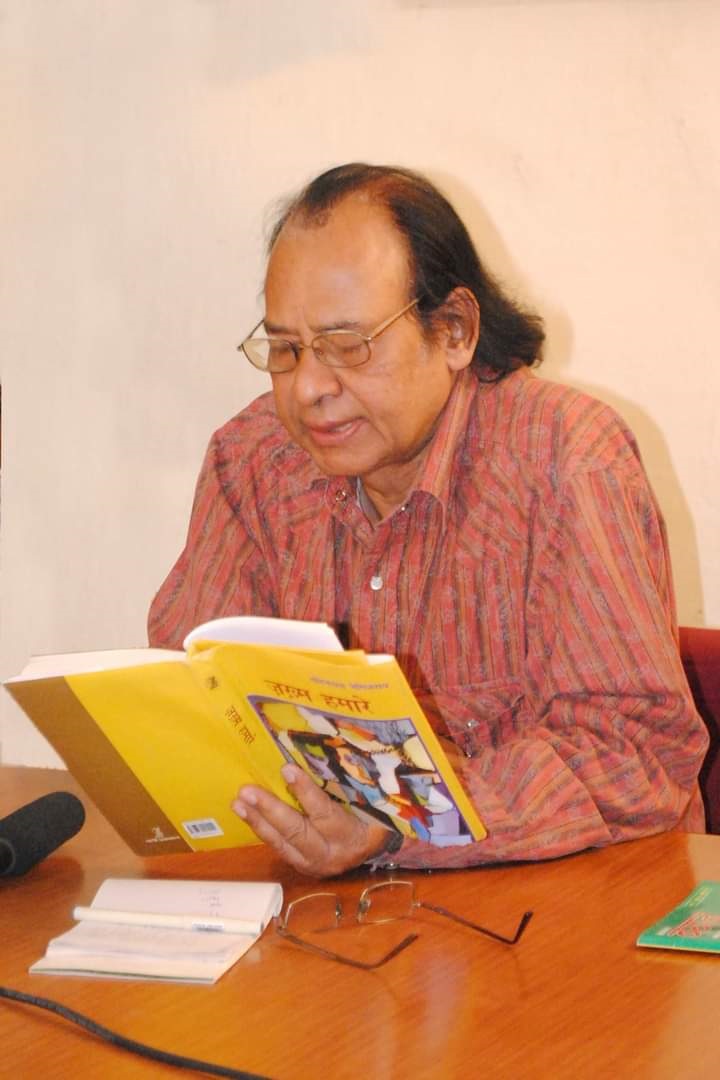

Mohandas Naimishray has contributed immensely to the evolution of Dalit Literature to its modern form. He was born on 5 September 1949 in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. After acquiring an education against all odds, he briefly worked as a lecturer in a college in Meerut before going on to devote the rest of his life to Dalit journalism and literature. As a journalist, he raised issues related to Dalits and the problems they were facing in many national newspapers and magazines. He was equally frank and fearless as an author. His autobiography is published in three parts: Apne-Apne Pinjare (Part 1), Apne-Apne Pinjare (Part 2) and Rang Kitne Sangh Mere (Part 3). Among his published works are Awazein, Hamara Jabab and Dalit Kahaniyan (collections of short stories); Kya Mujhe Kharedoge, Muktiparva, Aaj Bazar Band Hai, Jhalkari Bai, Mahanayak Ambedkar, Jakhm Hamare and Gaya Mein Ek Adad Dalit (novels); Adalatnama and Hello Comrade (plays); and Safdar Ek Bayan and Aag Aur Andolan (anthology of poems). In addition, he has authored Dalit Patrakarita Ek Vimarsh (four volumes), Dalit Andolan ka Itihaas (four volumes) and Hindi Dalit Sahitya. He was the editor at Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Government of India, for almost six years. He has also edited the Bayan magazine. In 2011, he was honoured for his exemplary social and literary contributions by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar National Institute of Social Science, Mhow (Madhya Pradesh).

Mohandas Naimishray is a representative writer of Dalit literature and an extraordinary essayist. Awazein, his first collection of short stories, came out in 1998. Hamara Jawab (2005) and Mohandas Naimishray Ki Chuni Huyee Kahaaniyan (2017) followed. The short stories by Mohandas Naimishray, who is considered among the founders of Dalit Literature, expose the cruelty of feudalism and caste-based exploitation.

Naimishray’s short stories expose the feudal dominance of the upper-caste people in the rural areas. They present casteism and feudalism as two sides of the same coin. For instance, Apna Gaon delves deep into the casteist and feudal misbehaviour of the savarnas and the atrocities committed by them. Both the men and women are faced with cruelty and ruthless behaviour of the upper castes. Feudal mindset and casteist arrogance are manifested in the insult of Dalit women in public places.

In Apna Gaon, atrocities and excesses that the Thakurs of her village subject Kabutari, a Dalit woman, to are a blot on humanity. Kabutari is disrobed and paraded through the village just because her husband Sampat was not able to repay their loan on time. The masculinity of men of feudal mindset is reserved for Dalit women like Kabutari. The pain Kabutari and her father-in-law Haria have to go through is the tragic consequence of feudal and casteist hegemony.

Even when Kabutari approaches the courts to seek justice, only humiliation and torture come her way. While casteist and feudal people prey on Dalits in the villages, police stations, courts and government departments are also habitual practitioners of casteism and feudalism. As a result, Kabutari and her husband are thrashed and driven away by the police station in-charge. The duty of the police is to protect the deprived from the atrocities of the powerful. Instead of securing justice to the deprived, it often covers up the atrocities and the excesses of the upper caste. Recently, in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh, a Dalit woman was raped and left to die with a severed tongue and a broken backbone. And when she died after spending several days in hospitals, the police had her body hurriedly burnt at night.

In most cases, the village panchayats are also dominated by the upper caste. That is why Kabutari and his family do not get justice from the village panchayat. Casteist atrocities are blocking the progress of Dalit community. When Kabutari and her family do not get justice, members of the Dalit community decide to carve out a separate village of their own.

Also read: Om Prakash Valmiki: Representative author of the marginalized

Through Awazein, Mohandas Naimishray, brings to the fore the anger and the resistance of the Dalits to the feudal and inhuman traditions. Under the Varna system, the unenviable tasks of skinning the dead cattle and disposing of night soil are reserved for the Dalits. As education is spreading among the Dalit castes, they are increasingly giving up these professions. In the short story Awazein, Itwari and others of his Mehtar community refuse to clean the leftovers and the dirt of the feudals. Autar Singh sees this decision of the Mehtars as an assault on his ego. His feudal mindset is not ready to accept that the Bhangis can give up the work of cleaning the muck and take up a dignified profession. To teach them a lesson, Autar Singh has their settlement set afire at night. This story depicts powerfully how harrowing feudalism can be for the Dalits.

There is structured inequality within the Brahmin community, too. Mohandas Naimishray’s another short story, Mahashudra Mahabrahmin, brings to light the casteism within the Brahmin community. Acharya ji is a Brahmin. He conducts the last rites at cremation grounds. Due to his profession, Brahmins of high status look down on him. When Acharya ji tells Nandu Dom that when he visits the home of a Brahmin, he is asked to stay outside, the latter is very surprised. He asks Acharya ji, “Are there high and low among the Brahmins, too? Are Brahmins also untouchable?” Acharya ji replies, “We are called … but Nandu, do you know its meaning? … Mahashudra.”

Besides caste-related issues, many Dalit authors have also questioned the functioning of government offices. The hegemony born of the caste system has played a key role in depriving Dalits of justice. Upper-caste officers manning the government offices do not help the Dalits in getting justice. Instead, they try to scare them away. The upper-caste people committing atrocities on the Dalits get away with their influence on and their nexus with the officers of their caste. In many cases, the victims are turned into offenders.

Mohandas Naimishray’s Nizam (Hans, November 2019, Volume 34, Issue 4) systematically reveals the casteist oppression of Dalit prisoners by the police. Interestingly, this short story came out at a time when the ruling dispensation had been claiming that it is devoted to protecting the Dalits. Since the judicial system is not under the control of the Dalits, far from it, they have to face the cruelties perpetrated by the government and the local administration. In Nizam, jailor C.L. Dubey assigns works to the prisoners on the basis of their caste. If a prisoner is from the Bhangi community, he is given the job of cleaning the toilets and clearing muck. The story exposes the insensitivity of the jail administration through the pain of Mamdu, who is a Bhangi by caste and whose mother used to carry night soil on the head. Mamdu protests the atrocities committed by her mother’s employer on her. Instead of nabbing the offender, the police brand Mamdu as the criminal and throw him behind bars. Dalits are discriminated against even by the jail doctors. “The wounds of an untouchable are also untouchable – which the doctor refused to touch.” Prabhat Kumar, one of the characters of Nizam, asks himself, “Is there any piece of land in this country where injustice is not done to the Dalits?” The short story underlines the fact that until the government machinery sheds its pro-savarna mindset, Dalits won’t be able to get social justice and representation.

References:

Namishray, Mohandas. (2019). Mohandas Namishray Ki Chuni Huyee Kahaniyan. New Delhi: Anannya Prakashan

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

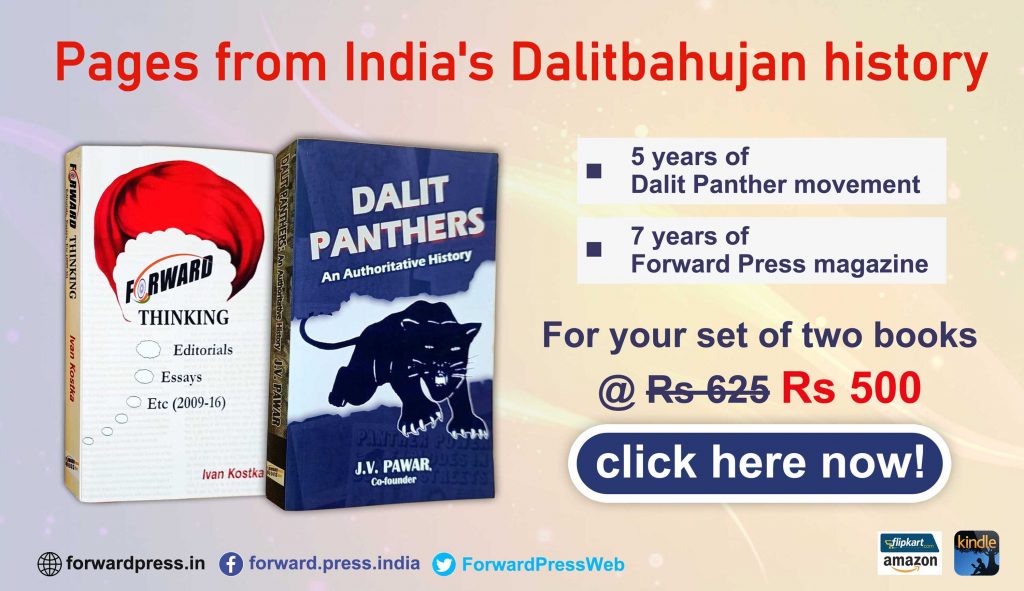

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History