Birsa Munda (15 November 1875 – 9 June 1900)

Today is 9 June. It is the martyrdom day of Birsa Munda (15 November 1875 – 9 June 1900) – the progenitor of the “Abua Disum Abua Raj” movement. He was also known as Dharti Aaba. His story begins with a 10-year-old Birsa protesting his teacher’s slur on the Adivasi community and consequently being thrown out from his school in Chaibasa. His name in the school records was Birsa David. He went on to raise his voice against the Indian Forest Act 1855, the British government’s atrocities against the Adivasis and its policy of usurping the land of the Adivasis.

Rebellion was already brewing

Birsa’s story may have begun in 1890 but the groundwork for it had begun decades earlier. The Permanent Settlement Act, promulgated by Lord Cornwallis, spelt trouble for the Adivasis residing in the lap of the Chotanagpur Hills for centuries. Prior to that, no ruler had interfered with the lives, the land and the forests of the Adivasis. Suddenly, the government started viewing land, forests and other gifts of nature as “resources” to be used for maximizing revenue and began ousting the Adivasis from their land. At the time, the Munda community followed an age-old custom called “Khunt Katti” under which each family was given exclusive rights to farm in and collect forest produce from an earmarked portion of the forests. Suddenly, dikus (outsiders) started making forays into their area. According to historians, by 1874, the dikus had established their control over all the settlements of the Mundas, reducing the Adivasis from landowners to labourers on their own land. A year later, Birsa was born.

Forest Act added fuel to fire

Then came the Indian Forest Act, 1882, which deprived the Adivasis of their rights over the forests. Beginning in 1885, the Adivasi chieftains raised the banner of revolt against the new law. Birsa, who was 10-year-old then, may have been influenced by this revolt, leading to his expulsion from the school in 1890. Birsa began mobilizing the Adivasi chieftains. He was caught in 1897 and was sentenced to two years in jail. It is said that when Birsa was released from the jail in 1899, his body was covered with “golden soil”. On 24 December 1899, Birsa sounded the bugle of Ulgulan. Historians describe it as a rebellion. But in fact, it was a declaration of war – a war against the dikus who had taken over the land, the water and the forests of the Adivasis. By 5 January 1900, Ulgulan had engulfed the entire region inhabited by the Mundas. On 9 January 1900, hundreds of Mundas laid down their lives while fighting the British on the Dombari Buru hills, near Ranchi, immortalizing the day in the chronicles of the Mundas. A large number of them were taken prisoners. Among them, two were sentenced to death, 40 to life imprisonment and six to 14 years in jail. In addition, three were punished with jail terms between 4-6 years and 15 others were sentenced to three years in jail. The British thought that Ulgulan was done with. However, the final and decisive battle of Ulgulan would be fought later that month itself again on the Dombari Buru hills. Thousands of Adivasis fought under the leadership of Birsa. However, their bows and arrows were no match for the guns and the cannons of the British. Thousands of Adivasis were said to have been brutally killed. The Statesman dated 25 January 1900, put the number of the dead at 400. The British won but could not capture Birsa.

Rs 500 award on his head

The British announced an award of Rs 500 for handing Birsa over to them. On 3 February, 1900, he was caught while he was sleeping deep inside the forests to the west of Sentra. His trial was conducted behind closed doors. He was charged with revolting against the government and spreading terror. No one was allowed to represent him. He was tortured in jail. On 20 May came the news that he was ill. On 1 June, there were rumours that he was suffering from cholera. He died in the prison on the morning of 9 June.

Novelist Mahashweta Devi writes in Jungle Ke Davedar: “At 8 in the morning, Birsa lost consciousness after vomiting blood – Birsa Munda, son of Sugna Munda, aged 25 years, undertrial prisoner. He was caught on the third of February but the British didn’t have a case against him and the other Mundas even at the end of the month. Birsa had been arrested under several sections of the Criminal Procedure Code but he knew that he would not be sentenced. A doctor was summoned. He felt his pulse. It had stopped. Birsa Munda had not died. The ‘god’ of Munda Adivasis was dead.”

Birsa’s martyrdom bore fruit

With Birsa’s death, Ulgulan also came to an end. But the chain of events forced the British government to sit up and take notice. The British realized that cultural issues could trigger another Adivasi uprising in the Jharkhand area any time. And so, it began making efforts to resolve land-related issues of the Adivasis. Land Bandobast (settlement) exercise was launched in the areas considered the epicentre of Ulgulan. For the first time, legal sanction was accorded to the Khunt Katti system through the Agriculture Amendment Act. Chotanagpur Tenancy Act, 1908, was enacted to legalize the system of land transfer and for effecting land settlement by preparing land ownership documents. The Chotanagpur Tenancy Act incorporated all the laws that were promulgated over the previous 25-30 years to quell resentment rooted in land issues. They included the Chotanagpur Landlord and Tenant Procedure Act, 1879 and Chotanagpur Commutation Act, 1897.

The new composite act afforded legal status to Khunt Kattidar and Munda Khunt Kattidar agricultural lands. It provided protection to traditional land rights of Khunt Katti villages and families. The deputy commissioner was equipped with special rights to allay the apprehension that outsiders may grab their land from the Adivasis. There was a provision for the externment of any such person who might attempt to do so. It allowed transfer of land between Mundas but disallowed it between Mundas and non-Adivasis.

Objectives of the British

All this, of course, was a part of the strategy to replace the self-governance setup in tribal areas with the British administrative machinery. The government initiated many administrative changes to implement the Act. In 1905, Khunti was made a sub-division and in 1908, Gumla was accorded the same status so that the Adivasis didn’t have to travel to faraway Ranchi to seek justice. The British destroyed the self-governing system of the Adivasis and replaced it with their own administrative system. But history is witness to the fact that Birsa’s movement became the gold standard for all the subsequent uprisings and agitations in the Jharkhand area.

Birsa, you’ll have to come back

Today, the situation in the Adivasi areas of India is worse than in Birsa’s time. Whether it is in Bastar or Kevadia, Niyamgiri or Netrahaat, Adivasis are being uprooted from their lands on the pretext of development. To make way for the dikus, Adivasis are being branded as naxals, killed in encounters or made to rot in jails for years without trial. The situation reminds one of these lines of Bhujang Meshram:

Birsa, you’ll have to come back from somewhere, anywhere,

From the sickle cutting grass or the axe cutting wood

From here or from there, from east, west, north or south

Come from anywhere my Birsa

Come like the breeze blowing over the fields

People are waiting for you.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

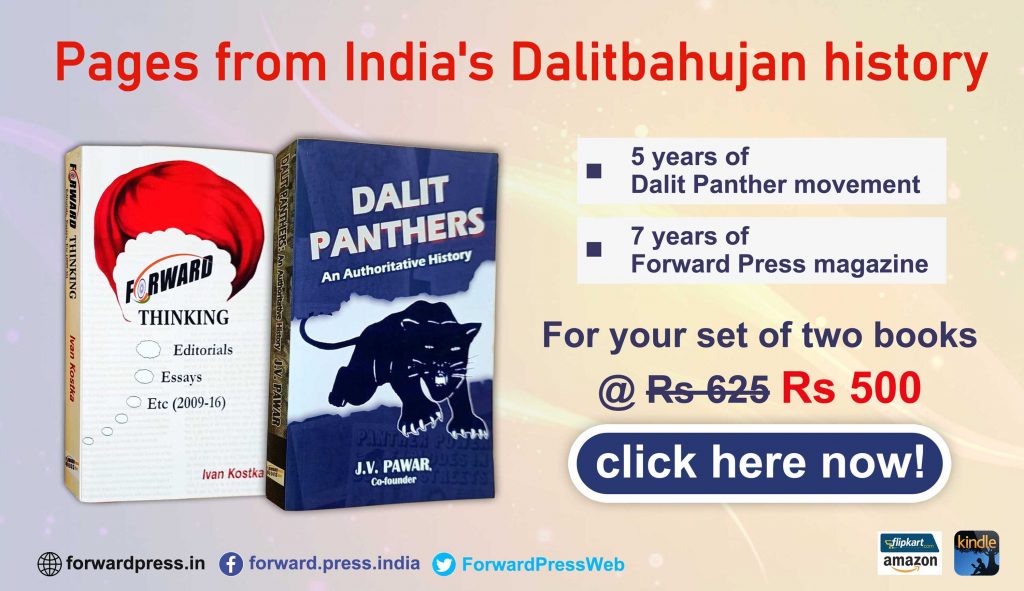

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History