The aboriginals or autochthonous (indigenous) peoples of India are known as Adivasis or Tribes/Tribals. The tribal population of the country, according to the 2011 census, is 104.3 million, constituting 8.6 per cent of the total population. Only 10.03 per cent of the tribal population lives in urban areas. Several scholars, like renowned sociologist Ghanshyam Shah, have classified the tribal population as Frontier Tribes and Non-Frontier Tribes – the former live in the northeastern states of India that share boundaries with neighbouring countries, while others inhabit the mainland of the country. In terms of the geographical distribution of the tribal population (based on the 2011 census), 76.8 per cent reside in North India, 11 per cent in South India (Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala), and only 12 per cent inhabit North East India (including Sikkim). Among the states, Madhya Pradesh is home to the largest tribal population – which is 14.7 per cent of the Indian tribal population. Maharashtra has the second-highest percentage of the tribal population – that is 10.1 per cent. Among the northeastern states, Assam has the largest share, 3.7 per cent, followed by Meghalaya’s 2.4 per cent

The Constitution identifies 705 Scheduled Tribes in the country, although sociologist Virginius Xaxa argues there are only 461 tribal communities. Article 342 of the Constitution defines Scheduled Tribes, and Article 338A provides the basis for establishing the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes. In addition to their rights as citizens, the Constitution has made special provisions for them, which range from recognition as Scheduled Tribes (Article 342), the establishment of a National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (Article 338A), “proportionate representation” in Parliament and State Legislatures (Article 330 and 332), reservation in state employment [Article 16 (4)] and institutions of higher education [Article 15 (4)] to empowering the State to give the area with a dominant presence of the tribes special treatment for administrative purposes. Within the backdrop of these Constitutional provisions, Xaxa has categorized different measures taken by states for their upliftment into three categories – protection, reservation, and development.

While the Constitution uses the term “tribe” for both the indigenous peoples of the Northeast as well as those of the mainland, the mainland tribes are commonly referred to as “Adivasis” rather than “Tribes/Tribals”, while frontier tribes are known as “Tribes/Tribals” rather than Adivasis. Even the Indian Constitution makes a distinction between them through the Fifth and Sixth Schedule, the former for Adivasis of the mainland and latter for the Tribals of the Northeast, respectively. The provision of the Fifth Schedule pertains to the welfare and advancement of Scheduled Tribes and the administration of the Scheduled Areas. Under this schedule, a provision exists for the extension of Panchayati Raj to the Scheduled Areas but this has proven ineffective, and even today, only six states have implemented this Act. Chhattisgarh is the seventh state in the process of implementing the PESA Act. The Sixth Schedule has provision for the formation of an Autonomous District Council, which is an autonomous body to carry out local-level governance.

Comparing the Tribals of the Northeast and mainland India, we find that the Tribals of the Northeast have done much better in several indices than their mainland counterparts. A report (based on the 2011 Census) prepared by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, says that the literacy rate of the Tribals of the northeastern states is much higher than their mainland counterparts. None of the mainland states with a significant tribal population has a literacy rate that exceeds 65 per cent. In the Northeast, the situation is the opposite – at 64.6 per cent, Arunachal Pradesh has the lowest literacy rate. The literacy gap (overall literacy rate minus literacy rate of the tribals) is very high in the mainland – in some states like Orissa, it is 20.7 per cent, while in Tamil Nadu, it is more than 25 per cent. Among the northeastern states, only Tripura has a gap of 8.1 per cent; in none of the others is the gap more than 4 per cent and in some states like Nagaland and Mizoram, the tribal population is even ahead in terms of literacy. According to the 2011 Census, incidence of poverty among Adivasis in the mainland states is higher than among the Tribals in the northeastern states. Incidence of poverty in rural areas is below 20 per cent in northeastern states. For some states in the mainland, the figure is more than 50 per cent, such as 51.6 per cent in Jharkhand and 55.3 per cent in Madhya Pradesh.

There is also a huge disparity in terms of the cases of atrocities against the tribes in the mainland and in the Northeast. According to the 2016 National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report, over the period 2014-16, Nagaland, Manipur and Meghalaya reported zero atrocities against Tribals while Madhya Pradesh accounted for 27 per cent, Jharkhand 4.3 per cent, Chhattisgarh 6.1 per cent and Andhra Pradesh 6.2 per cent of the total atrocities against Scheduled Tribes.

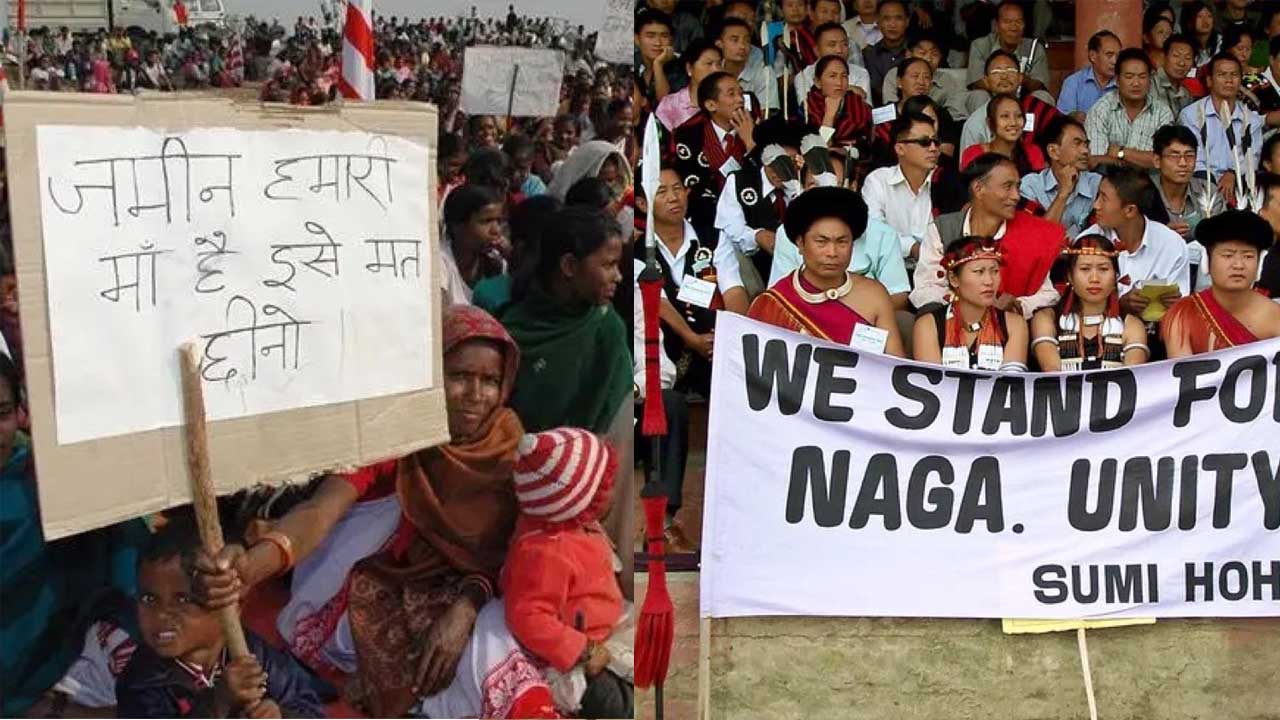

But what led to such disparities? In the Northeast, several factors have contributed to the better conditions of the Tribals. Early exposure to English-medium education after coming in contact with Christian missionaries raised the education levels of the Tribals, which in turn helped them better articulate their demand for rights. Second, they weren’t affected by the displacement caused by mining and land acquisition, which have made the Adivasis of the mainland particularly vulnerable. Third, the Tribals make up a large percentage of state populations in the Northeast – for example, northeastern states except Assam (12.4 per cent), Tripura (31.8 per cent) and Manipur (40.9 per cent) have tribal populations that exceed 60 per cent of their total populations. In the case of mainland states the upper limit remains 30.6 per cent (Chhattisgarh). Fourth, the Tribals of the northeastern states have had relatively little interaction with Hindus, which saved them from their varna and caste domination. Xaxa argues that close interaction with Hindus led to the assimilation of mainland Tribals, which jeopardized their political, economic, and social space. Fifth, they haven’t been politically active and are rarely found along India’s international borders, which has made them less assertive about their identity, while the Tribals of the Northeast are quite the opposite – they have been strongly assertive about their identity, which has given them greater clout in terms of governance.

These factors make the tribes of the Northeast better off than their mainland counterparts. But this doesn’t mean such huge disparities should persist. With smart policymaking, the Indian government can improve the quality of life of Adivasis – for example, giving them more autonomy in governance by extending the provision of Autonomous District Councils to Fifth Schedule Areas too, ensuring better representation in decision-making and the government, providing protection against deprivation of their rights over water, forest and land (jal, jangal, zameen) and minimizing displacement from mining. Making all of this a reality would demand political will.

(An earlier version of this article appeared in YouthkiAwaaz.com. It has been updated, edited and republished here with the author’s permission)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History