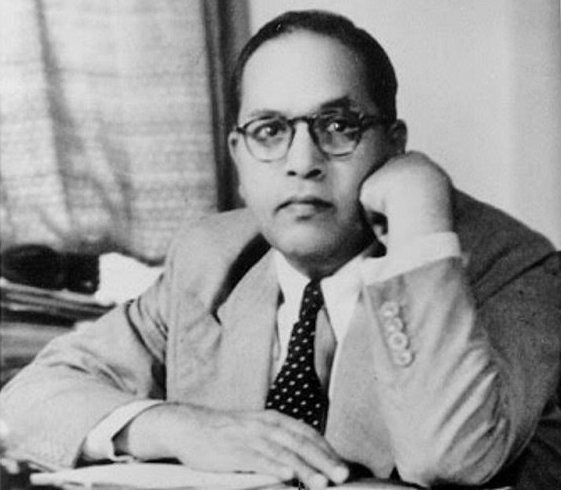

Manusmriti Dahan Diwas: 25 December 1927

On 25 December 1927, when the world was celebrating the birth of the prince of peace and liberation, Dr Ambedkar led in the burning of the book that legitimized the code of slavery in India. Today at this critical juncture in India’s history, where there is resurgence of the order of the brahmanical dwij (twice-born), it is essential to look for guidance from Ambedkar who fought hard to convert India into a casteless, classless and secular democracy.

Right from his early age Ambedkar was very critical of the Hindu religion. On 9 May 1916, in his first paper “Caste in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development” (BRAWS 1979: 3-22), Ambedkar analyzed the institution of Caste starting at its roots. He critically delved into the details of how Manu had legitimized and philosophized an inhuman code in these words:

“Every country has its law-giver, who arises as an incarnation (avatar) in times of emergency to set right a sinning humanity and give it the laws of justice and morality. Manu, the law-giver of India, if he did exist, was certainly an audacious person. If the story that he gave the law of caste be credited, then Manu must have been a dare-devil fellow and the humanity that accepted his dispensation must be a humanity quite different from the one we are acquainted with. It is unimaginable that the law of caste was given. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that Manu could not have outlived his law, for what is that class that can submit to be degraded to the status of brutes by the pen of a man, and suffer him to raise another class to the pinnacle? Unless he was a tyrant who held all the population in subjection it cannot be imagined that he could have been allowed to dispense his patronage in this grossly unjust manner, as may be easily seen by a mere glance at his ‘institutes’. I may seem hard on Manu, but I am sure my force is not strong enough to kill his ghost. He lives like a disembodied spirit and is appealed to, and I am afraid will yet live long.

One thing I want to impress upon you is that Manu did not give the law of Caste and that he could not do so. Caste existed long before Manu. He was an upholder of it and therefore philosophized about it, but certainly he did not and could not ordain the present order of Hindu Society. His work ended with the codification of existing caste rules and the preaching of Caste Dharma. The spread and growth of the Caste system is too gigantic a task to be achieved by the power or cunning of an individual or of a class. Similar in argument is the theory that the Brahmins created the Caste. After what I have said regarding Manu, I need hardly say anything more, except to point out that it is incorrect in thought and malicious in intent.”

Ambedkar understood that the Vedic texts emphasized brahmanical hegemony as the governing force of human interaction and exchange in a hierarchical order. Manusmriti legalized the enslavement mechanics into a code. Thus, the burning of Manusmriti was not just a significant symbolic act, but a socio-cultural and political action against enslavement at large.

Ambedkar proved that the religious doctrine played a significant role in strengthening the psychological enslavement of Indians. Through Manusmriti it was engraved on the minds of the “untouchables” that their wellbeing was in strictly following this religious code, which in turn would let them attain a better status in the next birth.

Revisiting the revolutionary Ambedkar of 1920s

The 1920s marked a radical transformation of the Dalit movement. There was a new awakening in Maharashtra, particularly against the violence of caste and untouchability. During the 1910s, Ambedkar was in the making as it becomes apparent from his in-depth articulation of caste as a systemic process of slavery. In the 1920s, his thoughts were more focused on the awakening of the masses. Both these decades were crucial in the life of Ambedkar. The 12-year phase from 1916 to 1927 consists of significant changes in Ambedkar’s life. It can be said that from the late 1910s to the early 1920s he searched for equality within the Hindu religious fold. By 1927, he had given up. He was sure that it was impossible for the Untouchables to have any liberation within the Hindu social system. He realized that the institution of chaturvarna could not be seen in isolation from the overall philosophy and theory of Hinduism. He developed the belief that the purpose/aim of human existence should be cultivation of the mind. No person should attempt to prevent another person exercising this right.

The anti-caste phase that preceded Ambedkar is also important to understand. The Dalitbahujan movement and writings acquired solidity in the mid-19th century, when Jotirao Phule’s Satyashodhak Samaj emerged Jotirao and his wife Savitribai became the first Indians to start a school for the Untouchables. His Din Bandhu was the first anti-caste Marathi periodical, perhaps the very first Bahujan periodical. In 1888, inspired by this periodical, Gopal Baba Walangkar – a retired soldier – became the first Untouchable to launch a newspaper. It was called Vital Vidhvasak (Destroyer of Brahmanical or Ceremonial Pollution) (Zelliot 2004: 42-44). Walangkar strove to remove the stain of untouchability and tried to convince caste Hindus of their inhuman behaviour (Keer 1954: 4).

The 1920s witnessed two significant moves by Babasaheb. First, he established the fortnightly newspaper Mooknayak (Leader of the Voiceless) and second, he formed the Bahushkrit Hitakarani Sabha (BHS). In Mooknayak, he argued that a nationalist consciousness couldn’t be developed by arrogantly ignoring social divisions. In the editorial of the inaugural issue of Mooknayak on 31 January 1920, he wrote:

“… inequality among the Hindus is as incomparable as it is hateful. Mutual dealings among the Hindus based on their inequality does not suit the character of Hinduism. It is clear that the castes that exist in Hinduism are inspired by the feelings of high and low. Hindu society is just like a tower, which has several stories without a ladder or entrance. The man who is born in the lower storey cannot enter the upper storey however worthy he may be and the man who is born in the upper storey cannot be driven out into the lower storey however unworthy he may be.”

Mooknayak thus took on the difficult task of documenting the agonies of the Untouchables within the ambit of the caste system. On 6 March 1924, Babasaheb convened a meeting to launch a social movement for the upliftment of the Untouchables in Bombay. The idea of the meeting was to establish a central institution for removing the difficulties of the Untouchables and placing their grievances before the government. BHS thus took shape on 20 July 1924 with the now-famous motto of “educate, agitate and organize” and became central to organizing and mobilizing the masses. This was the beginning of a new socio-economic and political movement to establish equality for the oppressed classes.

Consolidation of Brahmanism and Caste

Parallel to these developments, a constant consolidation of the brahmanical order of caste was taking place, which was reflected in the nationalist movement. The formation of the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) were key to this consolidation.

Madan Mohan Malaviya, Lala Lajpat Rai and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar launched the Hindu Mahasabha in 1915. In the 1920s, it came under the influence of Balakrishna Sivram Moonje. Under Savarkar, the Mahasabha played a stronger role in defending the brahmanical notion of purity of birth. His book Essentials of Hindutva tried to unite all Hindus castes and clans against Muslims and Christians. He says, “An Indian could be only that person who can claim his pitribhumi (fatherland), and who addresses this land of his religion as punyabhumi (holy land) both lay within the territorial boundaries of British India. These are the essentials of Hindutva – a common rastra (nation) a common jati (race or caste) and a common sanskriti (culture)” (Savarkar 1924: 43-44). Thus, the question of caste-slavery was left critically untouched as if all Hindus made a single nation, namely Hindu Rashtra, that went against the secular norms.

Then Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, one of the members of the Hindu Sabha, left the organization to form the RSS on 27 September 1925. Unlike the Hindu Mahasabha, the RSS stayed away from active politics and focused on the cultural front – on the creation of a Hindu cultural nation – and nationalism. Although ideologically similar to Mahasabha, the RSS grew faster across the nation and spread the ideology of purity of the dwij race. The initial impetus was to provide character training through Hindu disciplines upholding Hindu culture and thereby uniting the Hindu community to form a Hindu nation.

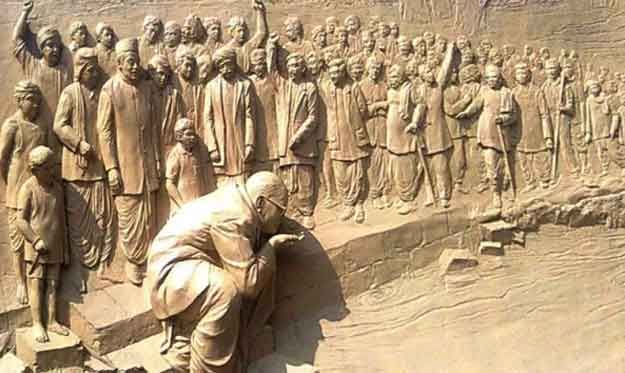

1927 Revolution

Ambedkar closely observed all these socio-cultural and political developments, and began asserting the rights of the Untouchables to live with dignity. On 1 January 1927, Babasaheb visited the victory pillar at Bhima Koregoan and held a ceremony to commemorate the battle of 1818. The British built it as a symbol of their power. He turned into a symbol of Mahar power against the Brahman Peshwa Raj. The Peshwas had persecuted the Dalits, so the Mahars joined the British Army in the battle against the Peshwas. Reminding them of the bravery of those Untouchable soldiers, Ambedkar instilled courage among the Dalits to fight the slavery of caste.

The Mahad agitation played a critical role in this mission. On 20 March 1927, Ambedkar led the Mahad Satyagraha or Chavdar Tale Satyagraha, demanding that Untouchables be allowed to drink from the public tank in Mahad. In this agitation, many upper-caste people also supported Ambedkar. It was the president of the Mahad municipality, Surendranath Tipnis, who announced that public spaces were open to the Untouchables. He had invited Ambedkar to hold a meeting in Mahad. After the meeting, the participants marched to the Chowdar tank. Ambedkar and thousands of fellow Untouchables drank from the tank.

Babasaheb appealed to the Dalit women present there to change their ways and throw off all symbols of slavery. The women readily wore saris like upper-caste women. Soon, caste Hindus violently confronted Dalits based on a rumour that Ambedkar and his followers were planning to march into a Hindu temple in the town. The struggle for the right to drink from a public water source continued.

The same year, on 26-27 December, Ambedkar planned for another conference in Mahad. The Brahmins had filed a case against him saying that the tank was not public property and the agitation had been called off. Yet, he decided to go back to Mahad. The caste Hindus blocked the road forcing Ambedkar to travel by sea. It is in this context that on 25 December, under the guidance of Ambedkar, a resolution was passed to burn the Manusmriti. The resolution read:

“Taking into consideration the fact that the laws which are proclaimed in the name of Manu, the Hindu lawgiver, and which are contained in the Manusmriti and which are recognized as the Code for the Hindus are insulting to persons of low caste, are calculated to deprive them of the rights of a human being and crush their personality. Comparing them in the light of the rights of men recognized all over the civilized world, this conference is of opinion that this Manusmriti is not entitled to any respect and is undeserving of being called a sacred book. To show its deep and profound contempt for it, the Conference resolves to burn a copy thereof, at the end of the proceedings, as a protest against the system of social inequality it embodies in the guise of religion.” (BRAWS 1989: 258)

Phule had made an appeal to burn Manusmriti and Ambedkar did it. This was the pivotal to the later phase of Ambedkar: In 1935, he announced that he would leave Hindu religion and in 1956 he embraced Buddhism. He played a revolutionary role in challenging the brahmanical social order and establishing a humanitarian social order based on the principles of equality, liberty and fraternity. These challenges stare at us today amid a reinforcement of the brahmanical order and the threat of a Hindu rashtra in the making.

Copy-editing: Ivan/Anil

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

References

B.R. Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 1. (1979). Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra

B.R. Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches Vol. 5 (1989) Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra.

Keer, Dhananjay (1954). Dr Ambedkar Life and Mission. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan.

Zelliot, Eleanor (2004). Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and the Untouchable Movement. New Delhi: Blumoon Books, 2004.

Savarkar, V.D. (1924). Essentials of Hindutva. Accessed at

http://www.savarkar.org/content/pdfs/en/essentials_of_hindutva.v001.pdf

on 10 November 2013