History is a chronological account of specific important and public events in the life of an individual, society or country. Myths, on the other hand, are the collective fantasies of prehistoric society, which, just like any other fantasy, are hazy, disparate and distilled. Broadly, all myths are products of imagination. Myths range from legends to traditional stories to the fanciful tales about gods and goddesses. Nevertheless, many myths are not just fantasy or gossip; they also present the contemporary social and historical reality. Over the course of time, some historical personalities turn into legends, for instance, Sultana Daku or Goonda Dhur. Some historical characters become part of idioms and proverbs while others like Gangu Teli and Guru Ghantaal tend to be used as disparaging references. Though Sultana, the dacoit, may have been a historical figure, many of his exploits described in folklore are imaginary. Similarly, Goonda Dhur also survives in the collective social memory in larger-than-life form.

Legend of Sultana

Sultana Daku was a real person, though many incidents supposedly related to his life, which have been portrayed in films, nautankis and folklores, are myths. The real life of Sultana has been obfuscated by the mist of fantasy. While the British, the Seths and the feudal lords branded him a dacoit, he was the darling of the common man, their sultan. He was really the sultan of the poor. The name Sultana was given to him by those who looked down upon him. Dr N.C. Shah, former scientist of Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, who has done research on Sultana, describes him as a man of character and grit.

Sultana Daku was a real person, though many incidents supposedly related to his life, which have been portrayed in films, nautankis and folklores, are myths. The real life of Sultana has been obfuscated by the mist of fantasy. While the British, the Seths and the feudal lords branded him a dacoit, he was the darling of the common man, their sultan. He was really the sultan of the poor. The name Sultana was given to him by those who looked down upon him. Dr N.C. Shah, former scientist of Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, who has done research on Sultana, describes him as a man of character and grit.

Sultana Daku was born in Harthala village of Moradabad Janpad, Uttar Pradesh. He was Bhatu by caste. Bhatu is a nomadic tribe. Sultana’s maternal grandfather lived in Kath. But the British resettled all Bhatus of Kath in Nawada. Sultana’s grandfather also moved to Nawada and Sultana spent his childhood there. Sultana became a legend in his lifetime. It was said that he used to loot the rich and distribute the spoils among the poor. This was his brand of socialism. It is a well-known fact that he was not a murderer. He himself said once that he had not killed a single human being. Yet, he was hanged on the charge of murdering a village Mukhiya. He was arrested on 14 December 1923 from the forests of Nazeerabad. The British government had to put together a special team under the leadership of Frederic Young to capture him. Young was considered an efficient and daredevil police officer. Well-known game hunter Jim Corbett was also a member of the group. Corbett, who was of Irish origin, later became known as a writer and philosopher. He lived at Kaladhoongi near Nainital and, like his sister, never married.

In the chapter “Sultana: Indian Robin Hood” of his book My India, showering praises on Sultana, Corbett makes an incisive analysis of his character. Is it not significant that Corbett, who took part in the operation to arrest Sultana, ended up praising him? Not only that, the police officer Frederic Young, who had arrested Sultana, resettled his wife and son at Belwadi, near old Bhopal. He gave Sultana’s son his name and had him educated in England. The son went on to become an ICS officer. Dr N.C. Shah gives an indication of the sterling qualities of Sultana when he writes that Sultana had twice spared the lives of Young and Corbett in the jungles.

In 1923, Frederic conducted 14 raids in quick succession in the area extending from Gorakhpur to Haridwar. Ultimately, on 14 December 1923, Sultana was arrested along with his key associates Pitambar, Narsingh, Baldeva and Bhure. Sultana was tried in the Nainital court, in what later came to be known as the “Nainital Gun Case”. After a long legal battle, Sultana was hanged in the Agra jail.

Natharam Sharma Gaud’s poetry and Aqueel Painter’s play chronicle Sultana Daku’s life. Natharam Sharma Gaud, a resident of Hathras in Uttar Pradesh, wrote the book Sultana Daku Urf Garibon Ka Pyara (Sultana Daku, alias the darling of the poor). Aqueel painter was from the village Chaandan in Lucknow district and wrote the book Sher-e-Bijnore: Sultana Daku. No play was as popular in the villages and mofussil towns of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar as the one based on Sultana Daku.

Search for Goonda Dhur

“Goonda” is the name of a Bahujan hero who fought the British. That is why the British started using the word “goonda” as a synonym for a bully or an anti-social element. According to Encarta dictionary, the word “goonda” was first used in the beginning of the 20th century. “Goonda” is basically a tribal word that has found a place in the English dictionary.

“Goonda” is the name of a Bahujan hero who fought the British. That is why the British started using the word “goonda” as a synonym for a bully or an anti-social element. According to Encarta dictionary, the word “goonda” was first used in the beginning of the 20th century. “Goonda” is basically a tribal word that has found a place in the English dictionary.

The name of this man who fought for India was Goonda Dhur. He had given the British a run for their money during the Bhoomkaal rebellion in Bastar in 1910. In the British government’s documents, Goonda Dhur has been described as a mutineer and “goonda” (rascal, thug, bully). In the eyes of the British, Goonda Dhur was a miscreant and a hooligan but for his countrymen, he was a courageous freedom fighter. A well-planned strategy for staging a revolt against British rule was crafted under the leadership of Kalendra Singh. At a meeting of the revolutionaries, Rani Subaran Kunwar announced the establishment of Muria Raj. At her suggestion, Veer Goonda Dhur was elected to lead the Bhoomkaal rebellion. On 1 February 1910, the bugle of freedom from the British yoke was sounded all over Bastar.

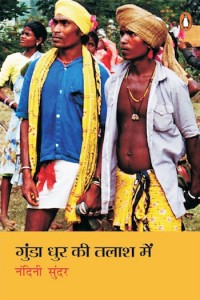

Recently, Nandini Sundar’s book titled Goonda Dhur Kee Talash Mein (In search of Goonda Dhur), published by Penguin Books India, has hit the markets. She writes in the book that she went from village to village asking about Goonda Dhur but few people had answers to her questions. “It seemed that barring the state government’s Tribal Welfare Department, few had any idea about him,” she writes. “The government has installed his statue treating him as a freedom fighter. I could see irony and assimilation in the statue but Goonda Dhur was nowhere to be seen.” The Indian dictionary writers, blindly following the British, have chosen to define “goonda” as “rascal”. It is their responsibility to purge the word “goonda” of its disparaging connotations and restore its real meaning, ie “brave freedom fighter”. Defining “goonda” as “rascal” is humiliating a Bahujan freedom fighter.

Proverbial Gangu Teli

If Raja Bhoj was a historical figure, so was Gangu Teli. In a village called Gadia in the Farukkhabad district of Uttar Pradesh, there is a huge “teela” (an elevated plateau) known as “Gangu Teli Ka Teela”. The palace of Gangu Teli was on this Teela. In the nearby village of Gauspur, there is an old Devi temple. It is said that Ganguli Teli had Gwalior’s Teli Mandir built. The Brahmins of Telangana had little to do with the temple. There are historical records that suggest that the Telis constructed the temple.

Truth of Guru Ghantaal

Guru Ghantaal was a Buddhist saint. Guru Padmasambhav had Guru Ghantaal temple built in his memory in the 8th century. The meaning of the word “guru ghantaal” also became distorted because of the clash between different cultures. Dictionaries define “guru ghantaal” as “a very cunning and sneaky person”. The meanings of some words became distorted because of the clash between Aryan and Dravidian cultures. One such word is “pilla”. In Tamil, “pilla” means a human baby while in Hindi it is taken to mean a puppy. Similarly, due to the clash between Jain and Brahmin cultures, the word “jinn” has come to mean a ghost.

Published in the October 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine