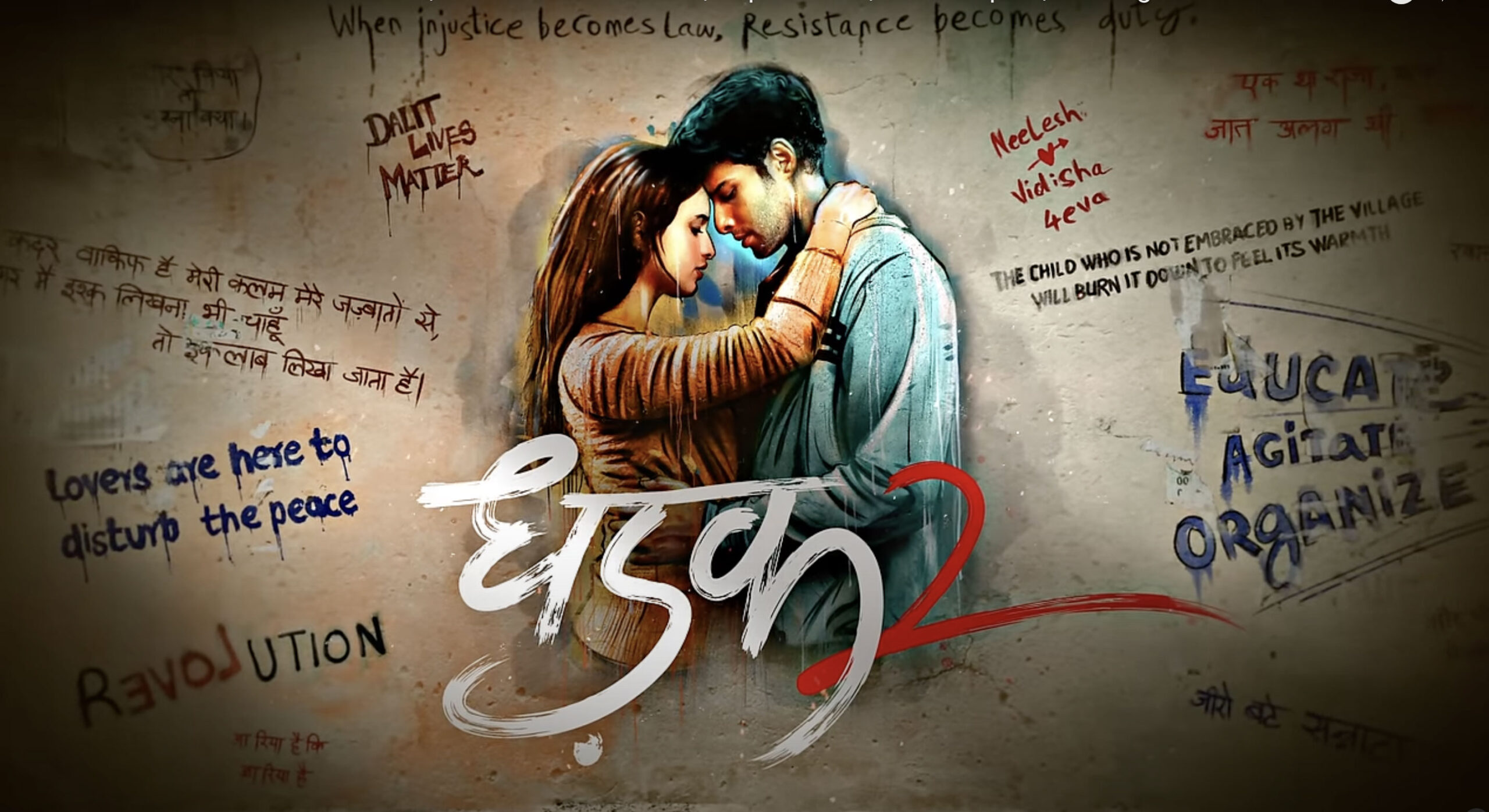

The barbaric police action in Patna on 3 August 2016 against Dalit demonstrators who were demanding their legitimate rights and dues has again underlined the fact that while both OBCs and savarnas want the votes of Dalit and Tribals, neither are really interested in treating them as equals. The behaviour of the police with students, teachers and Dalits under the Mandal JDU-RJD regime that holds aloft the flag of “social justice”, is exactly the same as it was in the Kamandal JDU-BJP regime that swore by “development with justice”. This is unfortunate, to say the least. What should be taken note of is the fact that the administration and the police resort to such barbaric action only when the protestors and demonstrators are from the deprived, exploited and marginalized sections of society. The casteist character of police and administration is evident in other situations too. The police remained a mute spectator in the aftermath of the murder of Brahmeshwar Mukhiya, the perpetrator of dozens of massacres, by the members of his own caste. There was an arson attack in the local Ambedkar Hostel and casteist rioting and violence in an 80km stretch from Arrah to Patna. The government inaction and delay in bringing the perpetrators to book in the Bagaha and Forbesganj police firing and the Shiromani Tola incident and the acquittal of all the accused of Dalit-OBC massacres prove that the administration and the police of Bihar are mere extensions of the casteist society that has persistently refused to change since Independence.

The barbaric police action in Patna on 3 August 2016 against Dalit demonstrators who were demanding their legitimate rights and dues has again underlined the fact that while both OBCs and savarnas want the votes of Dalit and Tribals, neither are really interested in treating them as equals. The behaviour of the police with students, teachers and Dalits under the Mandal JDU-RJD regime that holds aloft the flag of “social justice”, is exactly the same as it was in the Kamandal JDU-BJP regime that swore by “development with justice”. This is unfortunate, to say the least. What should be taken note of is the fact that the administration and the police resort to such barbaric action only when the protestors and demonstrators are from the deprived, exploited and marginalized sections of society. The casteist character of police and administration is evident in other situations too. The police remained a mute spectator in the aftermath of the murder of Brahmeshwar Mukhiya, the perpetrator of dozens of massacres, by the members of his own caste. There was an arson attack in the local Ambedkar Hostel and casteist rioting and violence in an 80km stretch from Arrah to Patna. The government inaction and delay in bringing the perpetrators to book in the Bagaha and Forbesganj police firing and the Shiromani Tola incident and the acquittal of all the accused of Dalit-OBC massacres prove that the administration and the police of Bihar are mere extensions of the casteist society that has persistently refused to change since Independence.

These experiences establish the following truths. One, a change in government does not bring about a change in the insensitivity of the police and the administration or in the manner of their functioning. Two, many politicians become insensitive once they come to power. Three, even if a party or a coalition is voted to power by a huge majority, it may not be able to exercise control over the government and administration machinery. Four, the repressive machinery of the state selectively targets the weak. Five, the dominant sections of society, even if they have not voted for the government, manage to make inroads into the government and the administration and secure their interests, and this translates into them never having to face the barbarity at the hands of the government machinery.

Because of their numerical strength or owing to some political compulsions, the Dalit, Tribal or OBC leaders may get to hold the reins of the government but because of a lack of Bahujan representation in the government and administration machinery, the retrograde forces are far from weak. The top leader may lay down the policies but they are sabotaged at the implementation stage. A Bahujan may be leading the government but the savarnas dominate the government machinery, and the police, administration, judiciary and media collectively ensure that the Bahujan leader does not have his way and ultimately is forced to take decisions that are against his political ideology and beliefs. The judiciary and the media play a key role here. The failure of Lalu Prasad Yadav to bring about fundamental changes in health and education and his keeping mum on the issue of land reforms has to be seen in this context. Another example is Nitish Kumar’s government decision to disband the Amirdas Commission, appointment of the Savarna Commission, putting the reports of Bandopadhyay Commission and of the Uniform Education System Commission headed by Muchkund Dubey into cold storage. It is really astonishing how the Bihar government is maintaining a stoic silence on the issue of reservation in promotions for SCs and STs and taking shelter behind court decisions. True, the government’s hands are tied by the judicial pronouncements but no one has stopped it from extending moral support to the measure. It could also have aggressively raised the issue of OBC reservations. Despite storming to power with a substantial support of Bahujan castes in November 2015, the Bihar government, as a matter of strategy, is soft on the savarnas and fighting shy of speaking its mind on many issues. This is not an isolated case. Governments led by Bahujans, under the pressure of savarnavadi groupings, routinely keep mum on key issues of social justice and representation.

The BSP-SP clash in Uttar Pradesh has come as a big shocker for the Bahujan politics. It is being used to pit the OBCs against the Dalits on political, social and psychological planes. Those doing this not only include the RSS, BJP, Congress and Leftist leaders of savarnavadi mindset but also some intellectuals and thinkers of SC-OBC communities spurred on by their vested interests. Under this policy, the savarnas in newspapers and TV channels are using Dalit discourse as a progressive mask to cover their casteist faces. Their apathy towards both Tribals and OBCs is clearly visible. What is even more disconcerting is that at a time when these communities need to launch a joint struggle to save the Constitution and reservations, they have started drifting apart.

All the OBC leaders of the country and vigilant citizens should consistently speak out on issues concerned with social justice and representation for Tribals and Dalits so that everyone can judge their policies, intents and behaviour and tell the difference between what they feel, what they think and what they say. This is also necessary to end the trust deficit between various Bahujan groups and to ensure that they are politically and ideologically united, at least on crucial issues. It may be mentioned here that Sharad Yadav was the first OBC leader to visit Una (Gujarat) after the shameful incident in that town. D. Raja had accompanied him. Sharad Yadav forcefully put forth his views during a 26-minute speech in Parliament on the excesses of the “gau rakshaks” in Una and on Dayashankar’s vulgar comments regarding Mayawati. His speech, delivered on 21 July 2016, shows how an OBC should respond when the Dalits of the country face repression or when the country’s tallest woman Dalit leader is humiliated.

All the OBC leaders of the country and vigilant citizens should consistently speak out on issues concerned with social justice and representation for Tribals and Dalits so that everyone can judge their policies, intents and behaviour and tell the difference between what they feel, what they think and what they say. This is also necessary to end the trust deficit between various Bahujan groups and to ensure that they are politically and ideologically united, at least on crucial issues. It may be mentioned here that Sharad Yadav was the first OBC leader to visit Una (Gujarat) after the shameful incident in that town. D. Raja had accompanied him. Sharad Yadav forcefully put forth his views during a 26-minute speech in Parliament on the excesses of the “gau rakshaks” in Una and on Dayashankar’s vulgar comments regarding Mayawati. His speech, delivered on 21 July 2016, shows how an OBC should respond when the Dalits of the country face repression or when the country’s tallest woman Dalit leader is humiliated.

To ensure that egalitarian developmental policies are adopted to meet the aspirations of the people in this pluralist country, it is necessary for the impact of the centres of social-political-economic pressure – which are built and operated by the top-down status quoist system – to be minimized. The only solution is a bottom-up social-political-economic pressure group. This would be like below-the-line or micro-level advertising. It is the responsibility of the Dalit-Tribal communities to build this pressure group. The 52 per cent OBCs have been caught between the centres of pressure of 15 per cent savarnas at the top and 25 per cent Dalit-Tribals at the bottom. They have to decide which group their future lies with and what their stand should be on social-political-economic issues. The OBCs will be the backbone of any struggle for societal and systemic change. On the one hand is the savarna community, which controls all centres of power and resources of the country. On the other hand, desperate to break free from their shackles, the Dalit-Tribals are growing increasingly aggressive. This is taking the societal dialectics to an interesting turn.

Against this backdrop, two options are available to the OBCs. One, to join hands with the deprived Dalit-Tribals and become a co-partner in the intellectual and ideological battle for bringing about social justice and change in India. Two, to bow to the pressure from the Manuwadi-brahmanical community, follow in its footsteps and fulfil its political-economic agenda by patronizing status quoist and feudal values. While the savarnas are in control of the centres of power and is pursuing an agenda of their own, in the long run, it appears that the Dalit-Adivasi joint front will emerge as a powerful force. On the other hand, there is lack of a community feeling among the OBCs, who form 52 per cent of the population. Due to casteist inequalities within the OBCs and the anger and frustration of the MBCs, there are so many conflicts within the OBCs that uniting them is a big challenge. This is also the biggest hurdle to achieving Bahujan unity.