The need for a discourse on the contribution of backward classes to the development of Hindi literature cannot be overemphasized. It is also necessary to analyze how this community has been presented in Hindi literature. The OBCs are the biggest chunk of Indian population. Because of the size, this section is also very diverse. The members of the community have diverse views on politics and religion. Admittedly, there are some contradictions, too. OBCs don’t have a single identifier unlike the Dalits, where untouchability – as a common identifier – helped build a discourse and laid the foundations of their politics and literature. Backwardness, in that sense, is not as precise a criterion.

It is being said that OBC literature is a far-fetched concept – that it is a casteist reading of literature, that it has no discourse or ideology and that its proponents are nobodies. On the one hand, the Dalit thinkers are insisting that OBCs are the patrons of Brahmanism and exploiters of Dalits. It is as if leftist scholars from the community do not exist. On the other hand, some OBC intellectuals have no qualms in demanding that a case be registered against those opposing OBC literature, because, they say, OBC is a constitutional term! Amid the clamour of these disparate voices and opposing views, one has to coolly and cogently decide what OBC literature is and how it is relevant and valid.

It is being said that OBC literature is a far-fetched concept – that it is a casteist reading of literature, that it has no discourse or ideology and that its proponents are nobodies. On the one hand, the Dalit thinkers are insisting that OBCs are the patrons of Brahmanism and exploiters of Dalits. It is as if leftist scholars from the community do not exist. On the other hand, some OBC intellectuals have no qualms in demanding that a case be registered against those opposing OBC literature, because, they say, OBC is a constitutional term! Amid the clamour of these disparate voices and opposing views, one has to coolly and cogently decide what OBC literature is and how it is relevant and valid.

In this context, one cannot help discussing the proceedings of the seminar on OBC literature, held at Dayal Singh College, Delhi, on 30 August 2016. Most of the speakers at the seminar seemed to have grave doubts about and disagreements regarding the concept. Some were supporting it, but their arguments were a classic example of oversimplification. The opponents had a long list of objections, while the supporters, without any concrete basis, were swearing by the validity of the concept. The audience was curious to know more but the speakers had little to offer.

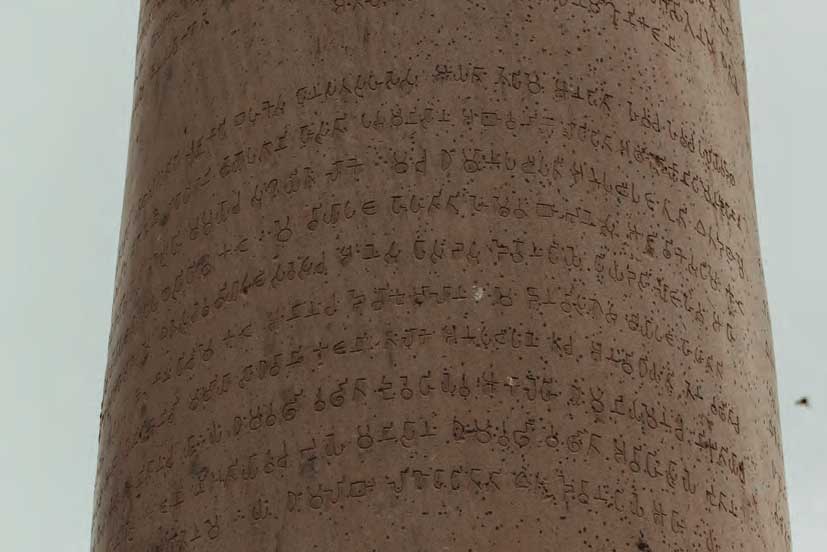

Instead of trading charges, it would make sense to think and write cogently and logically on the issue. Whatever may be the reservations of the doubters, what no one can perhaps deny is that there exists a caste group in India called the OBC. There might be differences of opinion on the tendencies and predilections of this group, and defining its nature may be a daunting proposition, but that is a different matter. The census conducted by the British government at the beginning of the 20th century gave, for the first time, a distinct identity to groups called “Dalits” and “OBCs”. While the untouchable and tribal communities were identified and listed, others were bunched together as the Backwards. Their identity remained unknown. Hence, this community has been facing a crisis of identity from the very beginning. It is in a majority in almost all cities, towns and villages but its members are dispersed. An identity based only on caste is well-defined but its boundaries are small. One cannot go far on the basis of only the caste identity. Caste-groups have a bigger say in society and politics and can be used for interventions.

Our limited concern here is how to recognize the literary expressions of the huge mass of OBC castes. Should they be left unidentified? Every litterateur belongs to one or the other caste but a literature cannot be developed on the basis of caste. Birth-based identity is an essential component of identity-based discourses on literature. However, while caste, creed, gender and race can be the springboard of a discourse, they cannot be its be-all and end-all. Dalit discourse will not grow merely by abusing non-Dalits; only putting men in the dock will not take women’s discourse ahead. Similarly, OBC literature will not develop only by focusing on caste.

Just as the OBCs are all-pervasive in India society, they are everywhere in Hindi literature, too. Barring purely romantic and courtly literature, the community figures in the writings of all litterateurs who wrote about the real society. Except a handful, all Hindi novels are about this community and so is the literature about farmers and farming, and the works on rural life. Whosoever attempted to present Indian society in its entirety could not keep this community out of their writings. Even the literature that is upset at the weakening of the Varna system holds the resurgence of the Shudras (backward castes) responsible for it! One can safely presume that the same is true of literatures of all Indian languages.

Just as the OBCs are all-pervasive in India society, they are everywhere in Hindi literature, too. Barring purely romantic and courtly literature, the community figures in the writings of all litterateurs who wrote about the real society. Except a handful, all Hindi novels are about this community and so is the literature about farmers and farming, and the works on rural life. Whosoever attempted to present Indian society in its entirety could not keep this community out of their writings. Even the literature that is upset at the weakening of the Varna system holds the resurgence of the Shudras (backward castes) responsible for it! One can safely presume that the same is true of literatures of all Indian languages.

It is being said that no writer would like to build his image as an OBC litterateur. Obviously, when there is no literature, how can there be a litterateur? These kinds of questions are cropping up because of the crude attempts at developing OBC literature as a parody of Dalit literature. The authors who write about Dalits are labelled as “Dalit litterateurs” without a second thought. This probably does not happen to anyone else. For a long time, Ambedkar was called a Dalit thinker, though now the modifier has been dropped and he is referred to only as a thinker. He is now seen as a thinker who thought about the Dalits. Here lies the answer to the question referred to above. “Dalit” could be the thematic identity of a literature. The theme (Dalit) and the means of exploring it (literature) – both need to be given equal importance. It was because of overemphasizing the theme and ignoring the vehicle of its expression that many writings of Dalit litterateurs fell short of excellence. It is not at all necessary for us to don the tag of OBC litterateur. The OBC community is so vast that it need not employ the strategy of Dalit literature. The majority community should scrupulously avoid using the politics of minoritism, as it can afford to be magnanimous. Minoritism is plagued by concerns of self-preservation; the majority sees its future in being flexible. OBC literature is vast and OBC litterateurs outnumber all others. It will do no harm if we allow them to remain untagged.

OBC literature should not be seen as only being identity-based. Identity becomes a key issue for communities that face deep birth-based discrimination. This discrimination is blatant and often a theory is crafted to justify and validate it. For instance, women, Dalits and Tribals were discriminated against quite openly, with scriptures and popular opinion providing a theoretical garb. This, however, was not true of the OBCs. That is why even the non-Dalit thinkers who support the concept of Dalit literature have reservations about using a similar concept for the OBCs. Rajendra Yadav had clearly said that there is nothing called OBC literature. Chauthiram Yadav and Premkumar Mani have also voiced their opposition to the concept.

However, the generation of OBCs that grew up amid the changes triggered by Mandal politics has a different take on the issue. This generation is keen on increasing its representation in every field. They know that they are talented, able and hard-working. They have realized that the reason they are not forging ahead is not because they don’t have “merit” but because they are being deliberately and consciously pushed back. They want their place in the sun. They also want to leave a mark in the field of literature. Hindi literature has to respect this desire, for otherwise, it won’t be able to appreciate this yearning. This generation is aghast that every farmer in Premchand’s works is an OBC but critics do not even seem to note this fact. Hindi criticism does say that Premchand’s farmer is exploited and oppressed, but doesn’t identify his caste-group. Let us not speculate on what the objective might be because one cannot casually hurl baseless charges at great critics like Ramvilas Sharma. With all respect to them, all one can say is that they didn’t identify this section of society in their criticism. The members of the new generation wants Premchand’s farmer to be recognized as the member of the backward caste-group and for the characteristics of this group to be underlined. If Indian culture is agrarian, there can be no doubt that the OBCs – the only practitioners of farming – played the biggest role in building it. This kind of analysis is not possible without an OBC literary vision.

The analyzing and understanding of the mutual relationship between the OBC community and Hindi literature – from all angles and perspectives – should gather pace. The first thing to be done is to develop a vision of criticism. A critical understanding helps build an ideology. As the process of viewing and understanding Hindi literature from the OBC perspective grows, the concept will become clearer.

In terms of caste, the Indian society is divided into three broad sections – upper castes, OBCs and Dalit-Tribal communities. Identifiers of these communities are domination, contribution and pain, respectively. The upper castes always wanted to be dominant and whatever they did was to establish their domination. All their efforts were directed to that end. The OBCs have made the biggest “contribution” to the building of India through their toil in the fields of agriculture and artisanship. They were the producers. The contribution of all other caste-groups pales in comparison with theirs. At the same time, no other caste-group has had to undergo as much “pain” as Dalits and Tribals.

The OBC literary vision should try to bring to light the importance of the contribution of the OBC community. Farmers should not be seen only as an exploited community; their contribution to culture should also be highlighted. If we think of farmers as a caste-group, we will be able to identify the landlords who have infiltrated peasant politics. Kuber Nath Rai has written an essay titled Sanskriti Ka Sheshnag. In it, he has described himself as “Kisan Brahmin”. He is seeking to create an illusion that Brahmins are farmers. The farmers have their own culture, which is not at all compatible with that of the Brahmins. The upper castes may be landowners, farming might be the source of their income, but they cannot be farmers. In the heyday of socialism/leftism, it was fashionable to describe the upper-caste writers as “born in a farmer family” on the flaps of their books. Even while not doubting the intentions of such writers, one has to say that this is a sort of “forged identity”. In democratic India, many kinds of pseudo identities were created to prove one’s progressive credentials. Poverty was glorified, abetting the conspiracy to keep the real poor deprived and wretched.

OBC writers never needed to write their autobiographies and never will need to in the future. This is something writers associated with identity-based discourse are required to do, for autobiographies afford them space to express their “pain”. The OBCs don’t need to market their pain. They are brimming with good cheer, born out of labour, creation and production. Premkumar Mani has very rightly described Kabir as a “poet of cheerfulness”. Kabir was about toil, creation and production. Why would he lament and cry? That is probably why Kabir was not drawn to natural beauty. His poetry does not dwell on the beauty of nature. Ditto with peasant literature. The farmer characters of Premchand are not drawn to the beauty of nature, though they do sometimes appreciate nature as a fulfiller of their wants. On the other hand, half of Kuber Nath’s essay is devoted to describing nature. This is the difference between a real and a pseudo farmer.

OBCs are both Hindus and Muslims. Both groups never negated religion. Religion never caused problems for Muslim OBCs, though the Ashrafs dominated the religious set-up. Hindu OBCs always felt suffocated by the domination of Brahmins but they never had any reason to quit Hinduism. Conversions were limited to the Dalits and the Tribals. This is one reason why the OBCs were not drawn to Leftist politics, despite it taking on the Hindu religion. The OBCs were drawn to politics aimed at dismantling the domination of the upper castes but they were never resentful of Hindu religion as such. We should explore the role of OBCs in expanding the ambit the Hindu religion. We should not allow only the Brahmins to walk away with the credit for the flourishing of such a vast religious tradition. The Brahmins, of course, succeeded in establishing their domination over this religious tradition but that was because all upper castes were driven by a desire to control the levers of power.

The farmers and artisans were steeped in religion and spiritualism. Their work had a spiritual dimension. They performed religious rites at different stages of their work but they did not need the help of a pandit. Farmers perform these rites with the help of their families. That is another reason why, despite being desirous of breaking the domination of the upper castes, OBCs never rose against the Hindu religion. But their religion was not brahmanical. They were religious but not patrons of Brahmanism. Unlike Dalits, the OBCs need not hunt for a respectable place for themselves in other religions. Had the OBCs not taken the lead, the Dalits could never have gathered the courage to take on the upper castes. The OBCs have no complaints against Hindu religion. They have complaints against the domination of the upper castes; they have complaints against their contribution not getting due recognition.

OBC literature has great potential. It may help bring to the fore the importance of the OBC community, which has been facing an identity crisis right from the time before Independence. What is surprising is that the caste-group that played the biggest role in the building of India is being put in the dock for trying to carve out an identity for itself in the field of literature. Those who are pointing the finger are either upset by the imminent end of their domination or have the misplaced fear that the rise of OBC literature will end their monopoly over “pain”. But the new generation of OBCs, imbued with the values of Mandal politics, has had enough of the antics of both the caste-groups. It will not fall into their trap. This generation knows that their contribution is something to be proud of and that they are superior because they are the possessors of the beauty of culture of labour. No one will give them a platform. They will have to build one of their own. Only then their voice will be heard and those on the other platforms will concede their importance.

For a detailed exposition of the concept of Bahujan literature, read Forward Press Books’ Bahujan Sahitya Ki Prastavna.

Contact The Marginalised Publications to order a copy; phone: 9968527911, email: themarginalisedpublication@gmail.com

The English edition of the book is titled The Case for Bahujan Literature, which is also available with The Marginalised Publication.

To order the books on Amazon, click here and here.

For the e-book version, click here.