Historically, caste has assigned privileges or deprivation or a bit of both depending on which rung you are on the caste ladder. While the privileges continue to be enjoyed and the deprivation suffered, their association with caste have not been fully acknowledged by the modern State. Take, for example, the reluctance to the releasing of reports of caste censuses.

Two caste surveys have been carried out this decade but the results of both have been kept under wraps. Nationally, the Manmohan Singh-led United Progress Alliance government conducted the Socio-Economic and Caste Census 2011, while in Karnataka, the Siddaramaiah government had assigned the Karnataka State Backward Classes Commission, then headed by H. Kantharaj, the task of carrying out “Socio-Economic and Education Survey”.

The “Socio-Economic and Education Survey” was a massive exercise. It cost Rs 147 crore and 160, 000 personnel had surveyed more than 13.5 million households over 45 days. It was expected to be released before the April 2018 assembly elections.

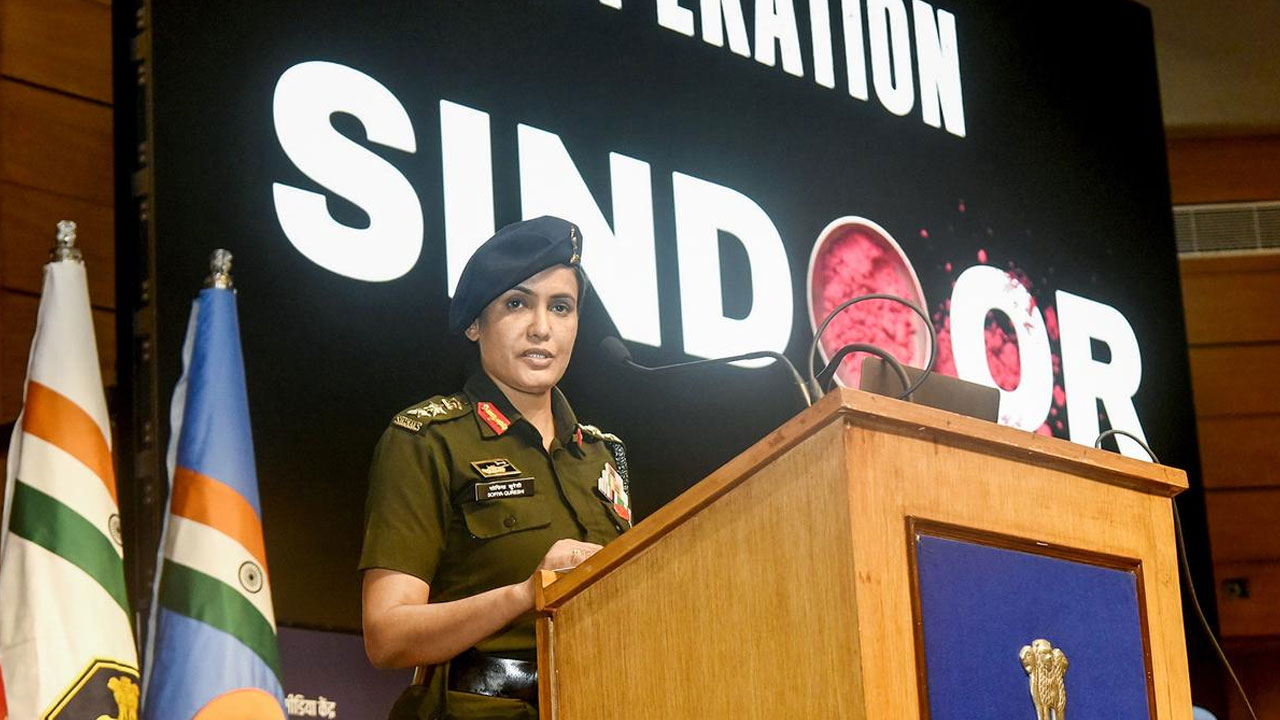

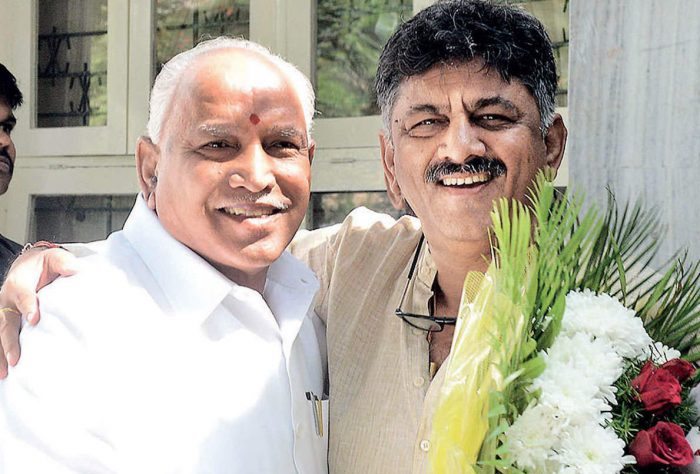

Recently, there have been reports of the present B. S. Yediyurappa-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government in Karnataka planning to junk the report of the “caste census”, as it has come to be known. In fact, Siddaramaiah himself had dithered on publishing the report before his term ended. There was no mention of the report when the H.D. Kumaraswamy-led JD (S)-Congress was in power.

Siddaramaiah belongs to the Kuruba caste. H.D. Kumaraswamy is a Vokkaliga and Yediyurappa a Lingayat. Even after the land reforms were implemented in the 1970s, Vokkaligas and Lingayats and the upper castes still own more than half of the land and make up a major chunk of the political class in Karnataka.

The Lingayats are the dominant community in North Karnataka while the Vokkaligas dominate the south, hence these pockets of dominance have translated into votes in both the Assembly and Parliament. On the other hand, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are scattered throughout the state. Despite being the largest community, the Scheduled Castes (comprising 101 jatis) own just 4 per cent of the land.

Siddaramaiah was one of the few non-Lingayat, non-Vokkaliga chief ministers of Karnataka. He had chalked out a plan that would reduce the role of the Lingayats or Vokkaligas in politics, which took the form of a coalition of castes called AHINDA – “Alpasankhyataru (minorities), Hindulidavaru Mattu (backward classes) and Dalitaru”.

While Siddaramaiah did not release the report, the data was leaked just before the April 2018 elections that ended his tenure as chief minister. “According to the census data seen by News18”, Scheduled Castes accounted for 19.5 per cent of the state’s population, Muslims 16 per cent, Lingayats 14 per cent, Vokkaligas 11 per cent, Kurubas 7 per cent, remaining OBCs 16 per cent, Tribals 4 per cent, Brahmins 3 per cent, Christians 3 per cent, Buddhists and Jains 2 per cent and others 4 per cent.

B.C. Mylarappa, a professor of sociology at Bangalore University and a leader of the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti, explains why the state government is reluctant to make the figures public: “It shows the Scheduled Caste and Schedule Tribe population as more [compared to the Lingayats]. The major castes, Gowdas [Vokkaligas] and Lingayats, have smaller numbers. The Chief Minister is also from the Lingayat community. The major castes haven’t been able to digest this. They were nervous when the statistics came out. It is becoming difficult for them to manage politically. They are saying the statistics are bogus, fabricated.”

It has been believed for decades that Lingayats are the largest community or at least on a par with the Scheduled Castes. The Venkataswamy Commission (1984) had stated that the Lingayats and the Scheduled Castes, respectively, were 16.92 per cent and 15.86 per cent of the population. The Justice Chinnappa Reddy Commission (1988) recorded 15.34 per cent for Lingayats and 16.72 per cent for the Scheduled Castes. The 2011 Census found that 17.15 per cent of Karnataka’s population were Scheduled Castes. Now, according to the leaked figures, the population of Lingayats has dropped to 14 per cent and that of the Scheduled Castes has risen to 19.5 per cent. Even the Muslims, who were around 11 per cent according to both the commissions, have left the Lingayats and the Vokkaligas behind in terms of population.

What would an approval of the report of the Socio-Economic and Education Survey mean? The Lingayat and Vokkaliga leaders in the BJP, JD(S) and the Congress, three major political parties of Karnataka, would be faced with demands from the Scheduled Castes for a larger role – for a larger representation in committees, a larger share of the Cabinet.

At present more than half of the MLAs in the Karnataka Assembly belong to Lingayat, Vokkaliga or one of the upper (Dwij) castes. Less than 15 per cent of the MLAs are from the remaining OBCs, 15 per cent from the SCs and a mere 3 per cent are Muslims.

N. Mahesh, an independent MLA, says there has not been an official announcement about the government rejecting the survey report. “This report has been submitted to the government. It has not been finalized. It is pending,” he says.

But he agrees that the government has taken far too long to publish the survey report. “How long can you hide these facts?” asks Mahesh, who is a former minister of Primary and Secondary Education, Karnataka, and a former state president of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). “Let it be known to the people and let them decide. It empowers the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, at least psychologically. They can ask themselves, “We are 25 per cent of population but what is the progress we have made in the last 70 years?’ We take their votes like we are purchasing vegetables in the market. What have they got in return from the system?”

Mahesh says that Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes have been getting “considerable representation” in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and Indian Police Service (IPS).

At present the Scheduled Castes are given 15 per cent reservation, STs 3 per cent and OBCs 32 per cent – Category I (comprising 95 castes) 4 per cent, Category 2A (105 castes) 15 per cent, Category 2B (Muslims) 4 per cent, Category 3A (Vokkaligas and five other sub-castes) 4 per cent and Category 3B (Lingayats and 42 sub castes, including Jains) 5 per cent.

But there is a catch. Mahesh explains: “Significant posts are given to their communities [Lingayats, Vokkaligas and upper castes] and insignificant posts to the SCs and STs.” If the miracle of the report being made public takes place, this could change, too. A historically deprived community of this size needs more than just representation, even proportionate representation. It needs meaningful, participatory representation.

Copy-editing: Ivan/Siddharth

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)