Casteism in India and racism in the USA are a disgrace to human dignity and impediment to progress. Both are products of twisted minds justifying every form of oppression and violence to seek and sustain power and wealth. Great men and women of vision and compassion fought against such prejudice, empowered the weak, and showed humanity a path of hope. Two such anti-caste icons of India, Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Babasaheb Ambedkar, appreciated the struggles of antiracism leaders of America. Ambedkar corresponded with W.E.B. Du Bois. How their attitudes and work ran parallel, built on each other, and even crossed paths across time and place is a fascinating history. Bridging the complexities of their contexts, distinct threads can be traced. Their stories provide historical depth to the struggle today, when racism is raising its hideous head and casteism continues unabated, promoted vigorously by renewed religious and political bigotry.

Jotirao and Savitribai Phule

The colonial period in India was marked by the emergence of brilliant anti-caste thinkers and activists who made significant contributions through speeches, writings, campaigns, advocacy and protest movements to expose the religious ideology and ideologues that were the cause of oppression of Dalits (Atishudras or Untouchables), Adivasis, Shudras and women. Jotirao Phule (1827-1890) and his wife Savitribai were the pioneers of this movement from the 1850s (Omvedt 2008). Prior to them there were several Christian missionaries helping the oppressed but their attacks on the caste system were localized and cannot be characterized as anticaste movements. Yet, missionaries were able to empower and provide dignity to the oppressed through education and employment, as well as promote group solidarity through fellowships.

Jotirao Phule launched a holistic movement that continues to inspire people today. Phule and his wife Savitribai launched an uncompromising attack on the evils of the caste system. Phule identified Brahmanism as the source of caste hierarchy and the consequent domination, discrimination, oppression, and untouchability. Thus began the first anti-Brahmin movement in the country (O’Hanlon 1985). Phule predates several other anti-caste leaders who emerged in the southern regions of the Madras Presidency who independently reinterpreted the history of India and organized effective anti-caste movements with large followings that empowered oppressed communities. These leaders include: Ayothithass Pandithar (1845-1914), Narayana Guru (1855-1928), Rettamalai Srinivasan (1860-1945), Ayyankali (1863-1941), Periyar (1879-1973), and M.C. Rajah (1883-1943). In Maharashtra just a year after the death of Jotirao Phule, Ambedkar (1891-1956) was born, undoubtedly the greatest of anti-caste leaders. Dr B. R. Ambedkar was an activist, sociologist, statesman and Constitution-giver for India. Ambedkar admired Phule, was inspired by him and dedicated his 1946 book, Who Were the Shudras?, to Jotirao Phule.

Background and achievements of the Phules

Young Jotirao Phule studied in an English school in Pune from 1841 to 1847. The school was opened by a Church of Scotland missionary, Rev James Mitchell, in 1834. Within six years there were 600 students in 11 boys’ schools and 5 girls’ schools located in Pune and Indapur. Mitchell and his wife Margaret also started a home for the poor and orphans. Phule’s education with Mitchell covered a wide range of topics characteristic of the English medium education in other Scottish mission schools run by Alexander Duff in Calcutta, John Wilson in Bombay and John Anderson in Madras. Their students became highly proficient and fluent in English. Among the many books Phule and his group of friends read, Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and Age of Reason made lasting impressions and influenced his actions. Phule subscribed for and also contributed articles on social reform to Dnyanodaya (The Rise of Knowledge), a magazine founded in 1842 by the American Marathi Mission at Ahmednagar. After Jotirao’s death, Dnyanodaya published an editorial obituary for him on 18 December 1890.

At Mitchell’s school Phule was influenced by Christian teachings, especially the values of equality and justice. In 1873, Phule founded the Satyashodhak Samaj (Truth-seekers’ Society) to free the oppressed by providing education, building up their self-respect, and awareness of their rights. He gave a central place to Jesus’ memorable advice, “Love your neighbour” and “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”. Phule makes repeated reference to this in his last book, Sarvajanik Satya Dharma Pustakis (The Book of the True Faith) (Phule (Patil) Vol II, 1991). He also turned the name of Jesus, “Yeshu”, into the Marathi name “Yashwant” or “Yeshwant”. His adopted son was also named Yashwant. In Gulamgiri (Slavery) Phule considers Jesus as the Baliraja of the West (Deshpande 2002 p 74, 75, 80, 88), often translated as Baliraja II by Patil (Phule; Patil Vol I, 1991 p 36, 38, 45, 59).

The Phules were pioneers in promoting gender equality; education of girls and women was a major component of their social reform movement. Phule taught his illiterate wife, Savitribai, who became a teacher. In 1848 Phule went to Ahmednagar, met with Cynthia Farrar and learnt how her schools were run. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) had sent Farrar to Ahmednagar in 1827. She was a pioneer in starting schools for girls, known as “The Farrar Schools” (ABCFM 1882 p 61-62). Following this visit Jotirao and Savitribai opened a school for girls in their home. Soon they were managing an impressive number of 18 schools for girls. On 15 September 1853 Dnyanodaya published a speech given by Phule on why he started a school for Shudra and Atishudra girls after visiting Cynthia Farrar (Jotirao 2020). Other schools were founded for Shudras and Atishudras – boys, girls, and adults. Today, Savitribai is claimed by many as the first Indian woman teacher because of her lifelong role in education. Undoubtedly she was also a feminist far ahead of her times. In 2014, the University of Pune changed its name to Savitribai Phule Pune University.

Like the Dalits, the condition of widows irrespective of caste, was most miserable during this period. The Phules opened a “home for the prevention of infanticide” in their house to help pregnant and exploited widows. A boy born to such one such widow was adopted by the childless Phules as their son Yashwant. Yashwant became a medical practitioner. After the death of Jotirao Phule in 1890, Savitribai and her son continued their social and medical service. The bubonic plague broke out in 1896-97 around Pune, so Dr Yashwantrao set up a clinic to treat patients. Savitribai Phule assisted him in the clinic and also brought in patients. Sadly, however, Savitribai was infected and died on 10 March 1897. Soon Dr Yashwantrao also died after contracting the disease.

Phule’s view on emancipation in the US

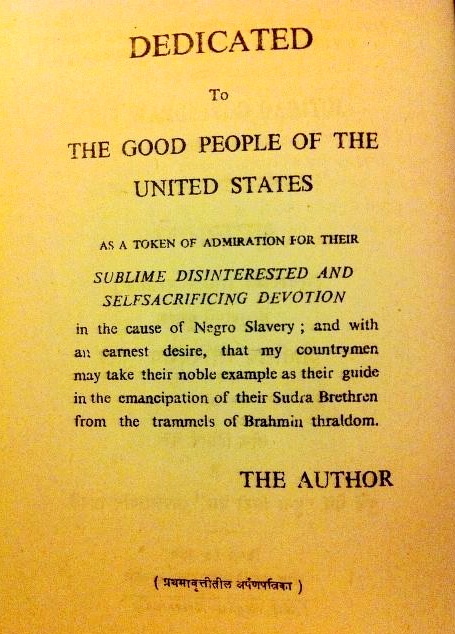

Phule was also aware of the condition of the slaves in the United States of America (USA) and the leaders who were in the forefront of emancipation. Among Phule’s more than fifteen writings, Gulamgiri (Slavery), published in 1873, is a work on race and caste. The central theme of this book is equal rights of all people. He challenged the brahmanical hegemony that violated the rights and equality of large sections of people by using religious myths. Phule debunked such myths and provided an alternative history centred around the righteous king, Bali, as the ruler who ensured the rights of all his people.

Phule admired the people of the USA for the abolition of slavery and hoped that their example would help in the emancipation of people in India. Just eight years before publication of his book Gulamgiri, the US Congress amended the Constitution in 1865 to permanently abolish slavery. President Lincoln was assassinated soon after. Phule dedicated his book “To the good people of the United States” for their “self-sacrificing devotion to the cause of Negro Slavery”. Phule must have had in mind not merely the formal declaration of 1865 but all the events leading up to it: the slavery abolitionist movement, the secession of southern states over the issue of slavery, and the ensuing Civil War between 1861 and 1865. Phule was appreciating all who opposed slavery as the “good people of the United States.” Indeed there were tens of thousands of men and women who worked to abolish slavery.

And there were abolitionist leaders – women and men who were born before Abraham Lincoln (1809). Two Black women, Elizabeth Freeman (Mum Bett) (c 1742-1829) and Sojourner Truth (c 1797-1883) were among the early courageous and inspiring leaders. A few other notable women leaders were: Lucretia Mott (1793-1880), Elizabeth Margaret Chandler (1807-1834), Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Tubman (c 1820-1913), who dared to rescue hundreds of slaves via the “underground railroad”, and Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906). Frederick Douglass famously wrote: “When the true history of the antislavery cause shall be written, women will occupy a large space in its pages; for the cause of the slave has been peculiarly women’s cause.”

In Gulamgiri, Phule compared the condition of the enslaved people in America with the oppressed people of India and hoped that like the 1865 abolition of slavery, there would be an end to all forms of caste discrimination in India. Phule wrote that the British rule helped free the depressed class from physical slavery. (During East India Company rule the British passed the Indian Slavery Act in 1843 banning all forms of economic slavery. Earlier in 1807 the British had abolished slave trade.) Phule hoped the Government would provide the necessary education and “pay attention to this urgent task” of education and help “free the masses from their mental slavery to the machinations of the Bhats” (Phule Vol.I 1991).

Fast forward to contemporary times

Interestingly, the phrase “mental slavery” used by Phule and his efforts to free the oppressed found parallels in African-American antislavery activists. Sixty-four years after Gulamgiri, in 1937, Marcus Garvey wrote: “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind.” About 1979 the reggae icon, Jamaican singer and songwriter Bob Marley used this same phrase “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery”, in his famous Redemption Song.

A century after the Civil War, the Black Panthers of the USA influenced Dalit activists in India: Namdeo Dhasal and J.V. Pawar founded the Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra in 1972 to counter atrocities against Dalits. A similar protective organization, the Dalit Panthers Iyakkam (Iyakkam means ‘movement’) was founded in 1982 in Tamil Nadu. Today it is known in Tamil as Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Kaatchi or VCK (Liberation Panthers Party). VCK is under the leadership of Dr Thol Thirumavalavan, who is a highly articulate speaker and writer with a large following of Dalits in the state. Thirumavalavan and another Dalit intellectual and prolific author, D. Ravikumar, were elected as Members of the Parliament in May 2019. Were Phule with us now he might be disappointed but not be surprised to see that the evil powers of casteism and racism are still surviving. He would applaud how people in both countries are still fighting for their equal rights, dignity, and a decent life. He would be in the forefront alongside all “good people” seeking justice for Dalits, Blacks, and oppressed people everywhere.

Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s correspondence with Dr W.E.B. Du Bois

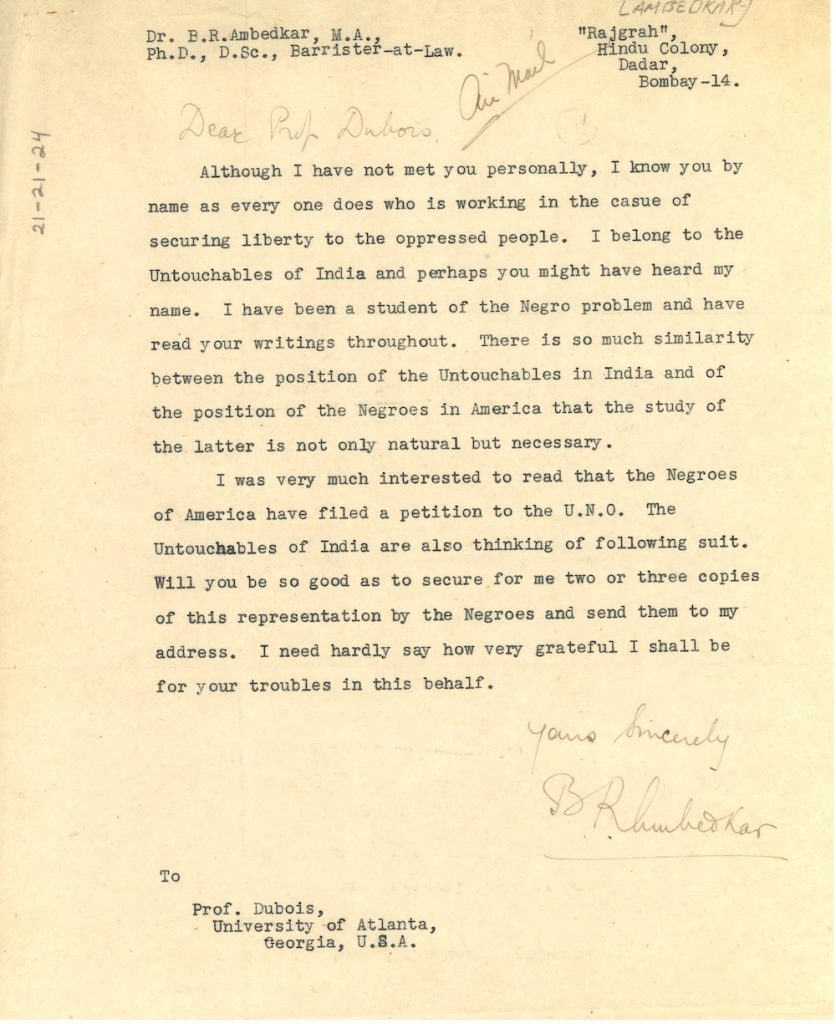

Dr B.R. Ambedkar corresponded with the prominent American Black leader Dr W. E. B. Du Bois in his effort to explore every possible avenue to liberate and empower Dalits. Ambedkar studied at Columbia University, New York in 1913-1916. It was there at the age of 22 he experienced the joy of freedom from the stigma of untouchability. He later recalled: “The best friends I have had in my life were some of my classmates at Columbia and my great professors”. On his return to India he again experienced discrimination and observed the cruel subjugation of Dalits. Liberation of the Dalits from oppression became Ambedkar’s personal mission for the rest of his life.

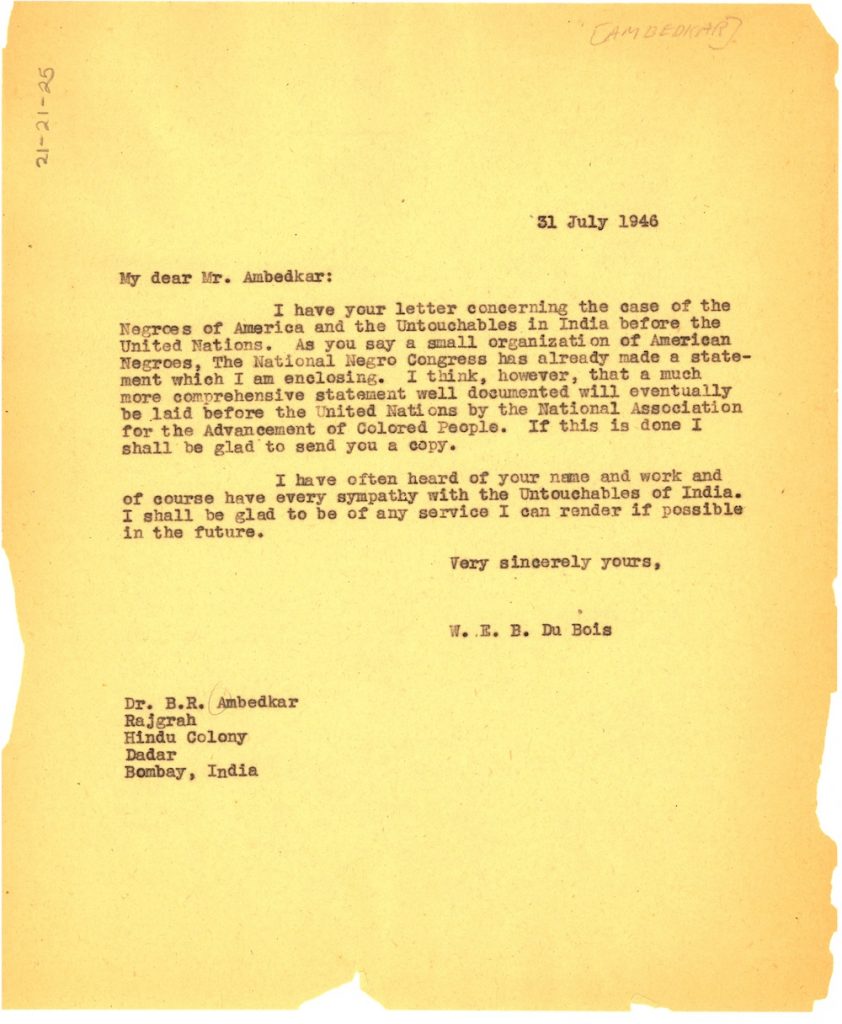

On 2 July 1946, Ambedkar sent a letter to Du Bois, whose reply is dated 31 July 1946. In his letter, Ambedkar pointed out that he had read Du Bois’ writings and found much similarity between the oppressed conditions of Black people in the US and the Dalit people of India. Ambedkar was interested in taking up the issue in the United Nations, and wanted copies of a representation that had recently been submitted to the UN. In fact, Ambedkar had examined the similarities and differences between the oppression faced by the enslaved peoples in the USA and Dalits in India in his essays. Ambedkar’s letter and Du Bois’ reply are reproduced below:

In his reply, Du Bois did send the document Ambedkar wanted and assured him of any help he could render in the future. It is not clear if Ambedkar was able to follow up the matter with the UN. Probably his time and energy in 1946 were consumed by the developments resulting from the decision of the British government to turn over power to Indian leaders. On the other hand, Du Bois was experiencing great frustration because his efforts to report racist practices in the US as human rights abuses to the newly formed UN were being completely blocked. This too may have been a reason why Ambedkar did not pursue the issue of Dalits at the UN.

Dr W.E.B. Du Bois the sociologist, writer and leader

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on 23 February 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, USA, to Mary Silvina Burghardt and Alfred Du Bois. His mother’s family was part of a group of free Blacks who were residents of the Berkshire Hills for more than a hundred years. His father was born in Haiti and was of French and African descent. Du Bois studied in Nashville, Tennessee, at Fisk University, a historically Black University, then went to Harvard to complete his BA and MA. He was a graduate student at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Germany, and obtained his PhD from Harvard University in 1895. Du Bois was the first African-American to receive a PhD from Harvard University. He was later awarded an honorary doctorate from Humboldt-Universität, Germany, in 1958. Du Bois served as a professor of history, sociology, and economics at Atlanta University from 1897-1910 and again 1934-44. He was a distinguished writer, editor, and leader of his people for more than half a century. It is not difficult to see that Du Bois’ life and interests have many parallels with those of Ambedkar.

Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, invited Du Bois to come to his country. Ghana was the first country in Africa (south of the Sahara) to gain independence. Nkrumah wished that Du Bois might be able to complete writing the Encyclopedia Africana, a project that Du Bois first envisioned in 1909. Du Bois had wanted to document the social, cultural, and scientific knowledge of Africa and the people of Africa who moved or were moved to other countries in the Old World and to other continents. He was also interested in writing about individuals who became intellectuals, scientists, artists and other prominent Africans and African-Americans.

A long and productive life came to an end on 27 August 1963 in Accra, Ghana, two years after Du Bois moved to Ghana and became a citizen there. He was 95 years old and died a day before the celebrated “March on Washington” under the leadership of Rev Martin Luther King Jr in which Dr King gave his memorable speech, “I Have a Dream”. Du Bois’ death in Ghana was announced on that day by Roy Wilkins, Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Du Bois was one among the interracial group of women and men who founded the civil rights organization, NAACP, in 1909. Toward the end of his life Du Bois was disappointed by the lack of progress he had hoped for in the liberation of African-Americans. He was also disillusioned by capitalism, as well as the entrenched racist stance of US political powers, and he therefore joined the Communist Party. He thought that capitalist ideology cannot reform itself, and universal selfishness cannot offer social good to all people. Du Bois renounced his American citizenship.

NAACP, The Crisis magazine and books

Du Bois’ travels in Germany, England and other European countries, the Soviet Union, China, Latin America and African countries had exposed him to various political, economic and social systems. He is recognized as an intellectual, activist, poet, sociologist, philosopher, professor, economic historian, journalist, and a social critic. He was a courageous civil rights leader and a foremost spokesperson for the rights of African-Americans during the early decades of the 1900s. NAACP, which he co-founded with other African-American leaders and abolitionist whites, protested against all forms of racial discrimination, violence, and unequal treatment of African-Americans. Du Bois was the first editor in 1910 of the official publication of the NAACP, The Crisis, and continued as editor for 23 years. It was so popular that within ten years, circulation reached 100,000 subscribers. This publication continues today, acknowledging the founding editor Du Bois. It is considered to be the most widely read and influential publication about racism and social justice in the history of the US (www.thecrisismagazine.com).

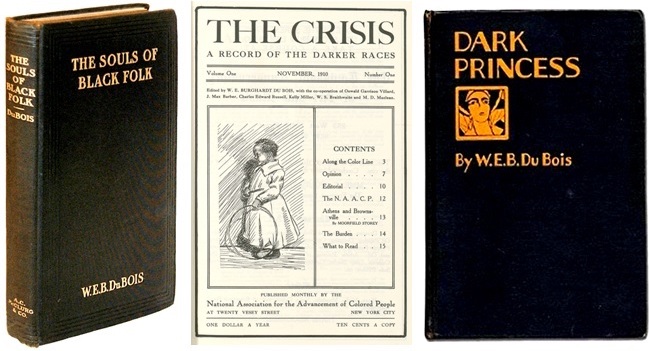

Among his writings is the most celebrated one titled The Souls of Black Folk, first published in 1903. The book is partly a social documentary, a work of history, an autobiography, and an anthropological account although it mostly deals with his approach to emancipation and empowerment of African-Americans. He wrote dozens of books over a span of 62 years, including Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880, Of the Dawn of Freedom, The Gift of Black Folk; and Against Racism.

Du Bois the international leader

Du Bois extended his scholarship and activism to include Black people worldwide, and is recognized as the “Father” of the Pan-African movement. It was at an initial conference in London in 1900 that Du Bois stated his brilliant prediction: “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.” This assertion was repeated in The Souls of Black Folk and is associated with him. He called for justice – not exploitation – of all people, whatever class, caste, privilege, or birth, but particularly regarding the European colonies in Africa. “Let no color or race be a feature of distinction between white and black men, regardless of worth or ability.” Du Bois called for the first large Pan-African Congress held in 1919 in Paris, parallel to the Versailles peace accord that ended World War I. Du Bois astutely wanted the voice of Black people to be heard at such a crucial time. Three more Congresses were held, with the bold leadership of Du Bois devolving to African leaders such as Nkrumah of Ghana.

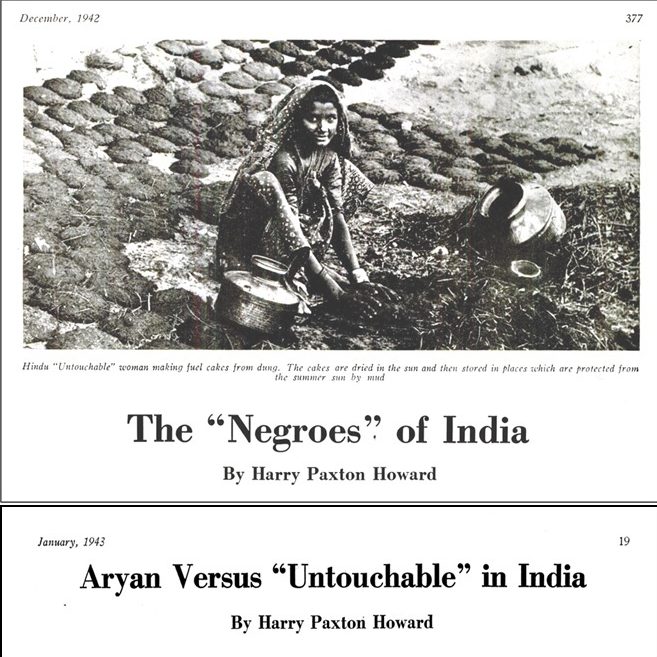

This international focus is evident in the issues of The Crisis. Interestingly, two articles titled “The ‘Negroes’ of India” and “Aryan versus ‘Untouchable’ in India” appeared in the December 1942 and January 1943 issues of The Crisis, highlighting the history of the plight of Dalits in India and introducing Ambedkar as their spokesperson. They were written by Harry Paxton Howard when Roy Wilkins was editor and appeared three years before the correspondence between Ambedkar and Du Bois. A vivid description of Ambedkar is found on page 378; Howard also makes a reference to Jotirao Phule in the second article.

“Harry Paxton Howard has lived in the Far East for 25 years, 5 years in Japan and 19 in China. He is the author of ‘The Socialist and Labor Movement in Japan’ publication of which caused his deportation from that country. He was the editor of various newspapers in China, among them the China Courier at Shanghai. At one time he was professor of Chinese diplomatic history at Soochow University. Since his return to the United States in 1940 he has been a prolific writer and lecturer on problems of the Far East.” (Editor’s note about the author)

In the 1920s Du Bois was interested in the people of India and their colonial rulers. The diversity of the skin colour of Indians must have fascinated Du Bois in his quest for an Afro-Asian solidarity of people of colour everywhere, as a revolutionary struggle against white supremacy.

Du Bois wrote five historical novels. One of them, titled Dark Princess (1928), features an African-American man who meets an Indian princess, Kautilya, a member of an international coalition of dark-skinned people who were opposed to Western imperialism. The novel provided a platform for Du Bois to express his favourite theme of the history of people of colour in the world, their beauty, and their contributions to society worldwide. His desire was to organize an international and pan-ethnic coalition of people of colour.

Parallels and connections

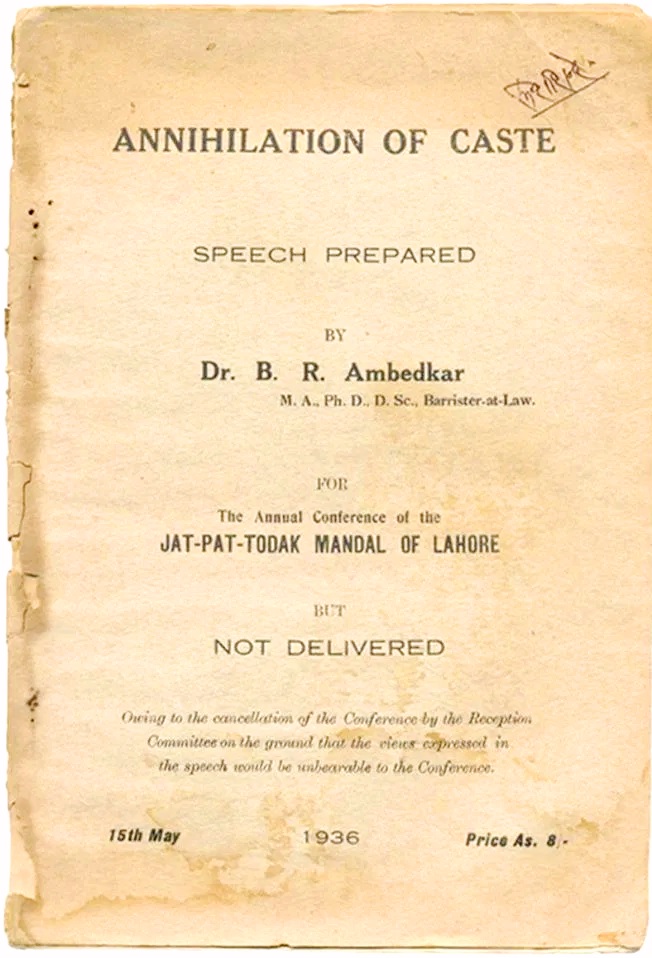

Like Du Bois, Ambedkar too was a prolific writer. He authored more than a dozen books; several others exist as incomplete manuscripts. Twenty-two volumes of his writings and speeches have been published by the Government of Maharashtra. Whether on political, economic, administrative, juristic, linguistic, anthropological, religious, philosophical or social issues, Ambedkar’s analyses are deeply penetrating and challenging. The very first paper presented by him in 1916 at a student seminar at Columbia University, Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development, remains a classic in understanding the Indian society. This beginning would lead him to further analysis of caste not as a division of labour but a division of labourers. He declared the Indian social system as one of “graded inequality”; of an ascending scale of reverence and a descending scale of contempt, and “an ascending scale of hatred and a descending scale of contempt”. Justice, equality, liberty, and fraternity were themes that shaped his life, actions, and writings. Du Bois too declared: “I believe in Liberty for all men … the right to breathe and the right to vote, the freedom to choose their friends …” A speech Ambedkar was invited to give in 1936 was cancelled by the organizers for his refusal to make certain changes suggested by them, but it still remains a most incisive analysis of caste. Ambedkar published it with the title Annihilation of Caste.

While Dalits have translated this work into other languages, still study and value the insight, the society at large has avoided reading or facing the implications of his conclusions. This reluctance to touch Ambedkar is equally true for all his other writings. The world at large has been slow to appreciate Ambedkar’s insights which are valuable for all countries, but in recent years more scholars are beginning to pay attention. Ambedkar’s directive, “Educate, Organize, Agitate”, should not be seen as advice only to Dalits in India, but equally applicable to oppressed people who seek justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity everywhere.

Du Bois was disappointed by the lack of progress in reforming American society. Ambedkar was disappointed with attempts to reform Hinduism and create a casteless society which he defined as a prerequisite for India to be a functional constitutional democracy. He converted to Buddhism, an egalitarian religion, in October 1956, fulfilling a declaration he made in 1935: “I will not die a Hindu.” A few months later and after completing his manuscript The Buddha and His Dhamma, he died in December 1956.

Ambedkar (1891-1956) and Du Bois (1868-1963) were contemporaries. Certain similarities in their approach to the process of liberation have been pointed out by scholars. Ambedkar studied at Columbia University from 1913 until 1916 June; then he left for further studies in London. He earned his MA in 1915 and completed his PhD at Columbia, then obtained an MSc and DSc in Economics at the London School of Economics, and also was admitted to the Bar.

In New York City, Columbia University is adjacent to Harlem, a neighbourhood which became a destination from 1904 onwards for Black people who were migrating in large numbers from southern states and from the Caribbean Islands. The era of Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), who advocated vocational education and accommodation as a strategy of survival for people in the deep south, was giving way to a new bold assertion of civil and human rights. The founding of the NAACP in 1909-1910 was a historical milestone. The connections between Columbia University and the NAACP are many and strong.

Two highly regarded members of Columbia’s faculty were on the first General Committee of NAACP: Ambedkar’s favourite mentors John Dewey, professor of Philosophy, and Ambedkar’s PhD guide, Edwin R.A. Seligman, professor of Economics and Social Science. Another prominent figure in NAACP was a graduate and former faculty member of Columbia: Joel E. Spingarn. He was chairman of the board, treasurer, and later the second president of NAACP, serving totally 26 years. All were closely connected with Dr W.E.B. Du Bois. Naturally, Columbia published some of the writings of NAACP. Faculty and students at Columbia would have read and subscribed to The Crisis that Du Bois edited. It is possible that Ambedkar was one of those readers, although we have no record of his writings on race during this time in the US. While Ambedkar and Du Bois were both in New York city at the same time they did not meet each other.

Role of the Arts in social struggle

The Crisis was very much a part of the Harlem Renaissance (c 1917-1930s), which was beginning to emerge while Ambedkar was in New York. The Harlem Renaissance was a movement of literary, artistic, musical, and cultural assertion by Black people, fuelled in part by the great migration and soldiers returning from World War I (1914-1918). The movement fed off and contributed to the social and legal rights struggle that was growing nationwide in reaction to increasing discriminatory and violent racism. All were indebted to the pioneering earlier work of the towering thinker, social reformer and abolitionist, Frederick Douglass (1818-1895).

Du Bois was convinced that arts played a role in bringing about racial equality. As editor of The Crisis Du Bois promoted the outpouring of many African-American performing artists and writers in the magazine. This was also the period when some leaders were active in proposing different strategies for the liberation and advancement of their people. Marcus Garvey from Jamaica, leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, advocated the resettlement of worldwide Black peoples to Africa. Du Bois and the NAACP differed widely from Garvey in approach and solutions. Du Bois also disagreed with Booker T. Washington’s earlier stand in accepting and accommodating to the existing social division. Du Bois worked relentlessly for total integration of the races.

Anti-caste activism in southern India

The modern transatlantic slave trade is about 500 years old. The Indian caste system, a form of birth-based slavery, is more than 2000 years old. Caste was a matter of consuming interest for many reformers. The Buddha condemned caste hierarchy as it was dividing society and leading to many evils. Caste began to crystallize after Manu codified the Manusmriti, a book of law including the duties and positions of the four Varna and outcastes in the first century CE. As the caste system spread to all regions of India during the next several centuries, there emerged protests and reformers; most of their stories have not yet been fully told. Songs of protest against the emerging birth-based discrimination can be seen in 2000-year-old Tamil literature. Among the greatest intellectuals was a Tamil Dalit, Thiruvalluvar, who condemned divisions and affirmed the oneness of the human family. His non-religious work of ethics, the Thirukkural, written as beautiful couplets, has been translated into more than 40 languages. Such protests against caste have continued ever since.

Some of the South Indian anti-caste leaders were active about the same time Du Bois was documenting the neglected culture, history, and achievements of African nations and leaders. An eclectic Tamil scholar, social reformer and activist, Ayothithass Pandithar (1845–1914), was deconstructing the prevalent storyline of Dalits popularized by the oppressive “upper” castes. He made powerful arguments about their Buddhist and intellectual past. Besides establishing a Buddhist and Dravidian organization (1891) he published magazines that were widely circulated and read by Tamils in India and the diaspora. In the neighboring state of Kerala too, there were leaders such as Narayana Guru (1856-1928) and Ayyankali (1863-1941) who challenged caste hegemony and promoted the cause of Dalits and other oppressed communities through organizations, protests and literature. A contemporary of Ambedkar in Tamil Nadu, E.V. Ramasamy Periyar (1879-1973), was a rationalist who worked for the eradication of caste and education of women. His tireless campaign against the exploitation of the marginalized and enslavement of people by superstitious priest craft resulted in a sea change in the minds of Tamil people and pride in their past; political parties continue his legacy today.

Similarities between Ambedkar and Du Bois

Du Bois promoted racial integration among all Americans and human rights for everyone. His stance was similar to Ambedkar’s later views in his seminal publication, Annihilation of Caste (1936), in the hope that the people of India will unite to affirm their common humanity. Later, Ambedkar would point out the differences between slavery and birth-based caste oppression. He felt that untouchability was an indirect form of slavery and was therefore more difficult to fight and overcome. Ambedkar wanted his people to obtain an education, gain employment, raise awareness and organize themselves to fight for their rights. He would say that they must not be fooled by paternalistic “intellectuals” who romanticized villages that in reality were cesspools of oppression. Du Bois realized that high-quality education was necessary for African-Americans to compete with Caucasians. This was one of the reasons that Du Bois helped to found The Crisis magazine and NAACP. Besides starting educational institutions, Ambedkar helped to start journals through which he could convey his views and raise the consciousness of his people. The first one was Mooknayak (1920) which ran for three years. Ambedkar continued to publish: Bahishkrut Bharat (1927-1929), Janata (1930-1956), and Prabuddha Bharat (1956). His plans to start a political party materialized only after his death (Republican Party, 1956).

As noted earlier, W.E.B. Du Bois was frustrated by the continuous blocks to achieving equal rights, prompting him to make a major change in his last years. He relocated to Ghana where he was warmly welcomed. It is interesting that B.R. Ambedkar, towards the end of his life, publicly rejected Hinduism and converted to Buddhism in 1956, five years before Du Bois left his country.

Dr Martin Luther King Jr: a fellow Untouchable in India

The exchange between Indians and Black Americans in the struggle for rights continued with Rev. Dr Martin Luther King Jr. It is well known that King based his non-violent resistance methods on those of M.K. Gandhi in the Freedom Struggle. In 1959 the Kings spent a month in India, where he realized deeper connections: “We were looked upon as brothers, with the colour of our skins as something of an asset.”

Their visit included a school in Trivandrum, attended mostly by Dalit students. In 1965, in a sermon at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, King recalled his experience: “The principal introduced me and then as he came to the conclusion of his introduction, he says, ‘Young people, I would like to present to you a fellow untouchable from the United States of America.’ And for a moment I was a bit shocked and peeved that I would be referred to as an untouchable … And I said to myself, ‘Yes, I am an untouchable, and every Negro in the United States of America is an untouchable.’

Lasting contributions

Both Ambedkar and Du Bois made enormous intellectual and practical contributions to counter the racist and colonial powers of the 20th century. Phule before them ignited the movement for liberation. The Constitution of India and the writings and life of Ambedkar continue to encourage all who seek a just world. The NAACP continues to be a national leader in the struggle for rights. These visionaries applied their outstanding scholarship to the struggle for the rights to freedom and dignity of minority peoples. They took a global outlook to include all oppressed people. Their achievements, writings, and legacies continue to be powerful forces and influence us today.

Racism and violence in many countries, as well as caste discrimination and atrocities against Dalits, are still perpetrated today in old and new forms. The archaic mindset and prejudice of people, especially those holding power, are increasingly visible with the global means of communication today. Manipulation of truth continues to incite division, violence, and oppression. As ever, the voices of Phule, Du Bois and Ambedkar ring true. Their intellectual arguments, political positioning, activism, bold and uncompromising stand on securing human rights for all people remain relevant for the transformation of societies everywhere.

(I thank the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts, Amherst for providing copies of the two letters. (A copy of Ambedkar’s letter is also reported to be found in the files containing his correspondence with the Cabinet Mission and with other leaders at Siddharth College Library, Bombay; see A.M. Rajshekhariah.)

References

Alridge, Derrick P. (2003). W. E. B. Du Bois in Georgia. Accessed from https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/w-e-b-du-bois-georgia

Ambedkar, B.R. Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Accessed from https://archive.org/details/Dr.BabasahebAmbedkarWritingsAndSpeechespdfsAllVolumes/page/n3

Note: In the collected works of Ambedkar chapter 3 of volume 5 is titled “Slaves and Untouchables” (pp 9-17). In chapter 8 of the same volume Part III is titled “Roots of the Problem”. Chapter 3 under the title “Parallel Cases” Ambedkar deals with the oppression in ancient Rome, Villeinage in England, Servility of Jews and “Negroes and Slavery” (pp 75-88).

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). Memorial Papers of the American Marathi Mission, 1813-1881. Bombay: Education Society’s Press, Byculla. 1882. Accessed from https://archive.org/details/memorialpapersa00missgoog on 15 January 2021.

Anderson, Carol. (1996). “From Hope to Disillusion: African Americans, the United Nations, and the Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1947.” Diplomatic History, Vol 20, No 4, pp 531-563. Accessed from JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24913318.

Beaver, R. Pierce. (1953). “Pioneer Single Women Missionaries”. Missionary Research Library. Occasional Bulletin. Accessed from http://www.internationalbulletin.org/issues/1953-00/1953-12-001-beaver.pdf

Bhalla, Tamara. (2018). “The True Romance of W.E.B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess”. S&F Online, Issue 14.3, 2018. Accessed from http://sfonline.barnard.edu/feminist-and-queer-afro-asian-formations/the-true-romance-of-w-e-b-du-boiss-dark-princess/) on 10 September 2020.

Brown, Kevin D. (2018). “African-American Perspective on Common Struggles” in The Radical in Ambedkar: Critical Reflections, edited by Suraj Yengde and Anand Teltumbde. Penguin Random House.

Dayanandan, P. (2019). “Ambedkar and Du Bois: In common pursuit of equality and justice”. Round Table India. Accessed from https://roundtableindia.co.in/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9742:ambedkar-and-du-bois-in-common-pursuit-of-equality-justice&catid=119:feature&Itemid=132

Deshpande, G. P. (1992). “Rajwade’s Weltanschauung and German Thought.” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 27, No 43/44, Accessed from JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4399063, on 3 April 2021.

Deshpande, G.P. (2002). Selected Writings of Jotirao Phule. New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

Du Bois, W.E.B. (1928). Dark Princess – A Romance. Banner Books. University Press of Mississippi (Recent editions have an Introduction by the Indian English scholar, Homi K. Bhabha).

Jones, Josh. (2016). W.E.B. Du Bois Creates Revolutionary, Artistic Data Visualizations Showing the Economic Plight of African-Americans (1900). Open Culture. Accessed from http://www.openculture.com/2016/09/w-e-b-du-bois-creates-revolutionary-artistic-data-visualizations-showing-the-economic-plight-of-african-americans-1900.html on 13 December 2020.

Kapoor S.D. (2003). “B.R. Ambedkar, W.E.B Du Bois and the Process of Liberation”. The Economic and Political Weekly, 27 December 2003, pp 5344-5349.

Keer, Dhananjay. (1964) “Mahatma Jotirao Phooley: Father of our Social Revolution”. Popular Prakashan. Second Edition. Accessed from https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13356/page/n5/mode/2up) on 4 January 2021.

Lewis, David Levering. (1993). W.E.B. Du Bois 1868-1919: Biography of a Race. Henry Holt.

O’Hanlon, Rosalind. (1985). Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge University Press.

Omvedt, Gail. (2008). Seeking Begumpura: The Social Vision of Anticaste Intellectuals. New Delhi: Navayana.

Pawar, J. V. (2017). Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History. Translated by Rakshit Sonawane. New Delhi: Forward Press.

Phule, Jotirao.(1991). Collected works of Mahatma Jotirao Phule, Vol I and II. Translated by P. G. Patil. Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, Bombay.

Phule, Jotirao. Selections from The Universal Religion of Truth (Sarvajanik Satyadharma Pustak). Accessed from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.7759/mode/2up on 2 April 2021.

Phule, Jotirao. “Jotirao Phule on why he started a school for Dalits”. Translation by the Satyashodhak staff, 13 September 2020. Accessed from https://thesatyashodhak.com/2020/09/13/jotirao-phule-on-why-he-started-a-school-for-dalits/) on 31 March 2021.

Phule, Jotirao. (1873). Slavery. Accessed from http://thesatyashodhak.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Jotirao-Phule-Slavery-Government-of-Maharashtra-1991.pdf on 2 April 2021.

Rajsekhariah, A.M. (1971). B. R. Ambedkar: The Politics of Emancipation. Bombay: Sindhu Publication.

Ray, Sibnarayan. (2003). “Phule to Ambedkar: An Unaccomplished Revolution”. Radical Humanist, March 2003, Issue No 396.

Sambaluk, Nicholas Michael. (2014). “Du Bois, W.E.B.” in “International Encyclopedia of the First World War”. Accessed from https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/du_bois_web on 14 Dec 2020.

Sivaiah, Tata (2017). “Remembering The Legacy of Mahatma Jotirao Phule”. Countercurrents. Accessed from https://countercurrents.org/2017/11/remembering-the-legacy-of-mahatma-jotirao-phule

The Crisis Magazine. (https://www.thecrisismagazine.com/). Historical issues from 1910 to 1922 are found at http://www.modjourn.org/render.php?view=mjp_object&id=crisiscollection

W.E.B. Du Bois. (2018). The Life and Legacy of Early 20th Century America’s Most Famous Civil Rights Activist. Charles River Editors. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Wilkerson, Isabel. (2020). Caste: The Lies that Divide Us. Penguin.

Witalec, Janet (Project Editor). (2003). Harlem Renaissance: A Gale Critical Companion. 3 Vols. Detroit: Gale.

Wolters, Raymond. (2002). Du Bois and His Rivals. University of Missouri Press.

Yee, Amy. (2017). “How W.E.B. Du Bois Found His Final Resting Place in Ghana”. The Daily Beast. Accessed from https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-web-du-bois-found-his-final-resting-place-in-ghana on 13 December 2020.

Yengde, Suraj. Caste Matters. Penguin Viking, 2019.

Yengde, Suraj and Teltumbde, Anand (Eds). (2018). The Radical in Ambedkar: Critical Reflections. Penguin Allen Lane. (See section on Ambedkar’s Struggle in the Global Perspective where six authors explore the shared struggles and liberation of African-Americans and Dalits).