At least since 1990-91, the Muslims have been supportive of the Dalits and the OBCs’ fight for social justice. The non-Congress, non-BJP parties have been dependent on the Muslims-Dalit-OBCs combine for their electoral victories. But the cooperation among those communities was not limited to elections or political agitations. In recent years, the minorities have consistently stood by the Dalits on issues related to atrocities perpetrated against them and their social rights. But this alliance does not suit the flag-bearers of communal ideology. At least that is the impression one gets from the violence, supposedly rooted in religion, that has broken out in different parts of the country recently.

What is common between the violence in Dakshinpuri (Delhi), Khargone (Madhya Pradesh), Karauli (Rajasthan) and Muzaffarpur (Bihar)? For one, violence broke out during religious processions. Second, the participants in the procession were waving weapons and their slogans, instead of hailing their own religion, were meant to disparage and abuse another religion. Third, the processions had a common destination – the place of worship of another religion. There was a pattern to the violence. First, stones were pelted on the processions and then the governments took action against the alleged stone-pelters. In fact, if you look closely, there are resemblances between the faces in the different processions.

Most of the riots were reported from places where the Dalits, the Extremely Backward and the Muslims had been living together in peace. These communities have deep, strong social, political and economic ties. But when it came to religion, they found themselves confronting each other. Clearly, these riots were not only about religion. They were designed to break the alliance that began shaping up in the 1990s. It is apparent that this time the pro-Kamandal forces have done their homework well while the Dalitbahujans are singularly lacking in the kind of leadership they had in the 1990s, including Kanshi Ram, Mulayam Singh Yadav and Lalu Prasad Yadav. While Mayawati is the political successor of Kanshi Ram, Mulayam and Lalu have handed over their political legacy to their sons.

The ultimate objective of the riots is to break electoral equations. But they are breaking other things as well. Communal violence doesn’t affect the individual victims only but also their communities. It is well known that after 1990, the Dalits and the OBCs, shunning crime, had voted to tread the path to social, economic and educational progress. After the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, a new consciousness had emerged among the Muslims. They came to realize the importance of social and educational development. These communities have progressed since then and this is not at all acceptable to some forces.

Also read – RSS talks religion but means Brahmanism

What is surprising is that those who are witness to the sanguine effect of social, economic and educational development on their communities want to hark back to the dark times. Instead of books and pens, their children are going about waving swords and guns. This should be a cause for concern for the OBC and Dalit communities. They are allowing their children and their youngsters to be used as fodder for stoking violence. Most of those who actually indulged in violence on the streets during the recent riots were from the Dalit and the OBC communities. And they were pitted against the supporters of their cause.

Undeniably, poverty, backwardness and social rivalry push people into a life in crime. This trend must have deepened due to the burgeoning unemployment and poverty over the past couple of years. The government itself has told us that 80 crore Indians are dependent on subsidized or free food grains. In such trying circumstances, a little greed, a little incitement, a little encouragement can push one towards committing violence. But this cannot be an excuse for doing nothing to arrest the trend. What is the way out? Should we retire to our homes, despairing that communalism will only grow with government patronage and that we can’t do anything to alter the situation?

Clearly, this is not the time to sit at home. At a time when the exploited communities are being pitted against each other to serve political interests, the saner and mature elements from both the sides need to work on the ground. The situation may be bad, but who is responsible for it? Shouldn’t those who have left their young to fend for themselves also share the blame? Why are these youngsters not being convinced that by falling into the trap of the vested political interests, they are ruining their future? Even if the government has to prosecute those involved in violence, it will make no difference to it. In fact, the government will only benefit from it. Issues like jobs and education would be pushed to the margins and the potential challenge from these communities would end.

These kinds of riots benefit the communal forces in more ways than one. Their core voters are happy that the minorities have been punished. Moreover, the socio-political alliance comprising 80 per cent of the population comes under strain, thus making it easy for the numerically inferior but socially superior classes to perpetuate their dominance. These are difficult times for those doing politics of the Dalits and the OBCs. If the Dalits, OBCs and minorities are at each other’s throats, who will be left to hold aloft the flag of social justice? These are among the questions confronting the Dalit and the OBC leadership of the country. If they don’t act in time, a day may come when they will become irrelevant in political terms.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

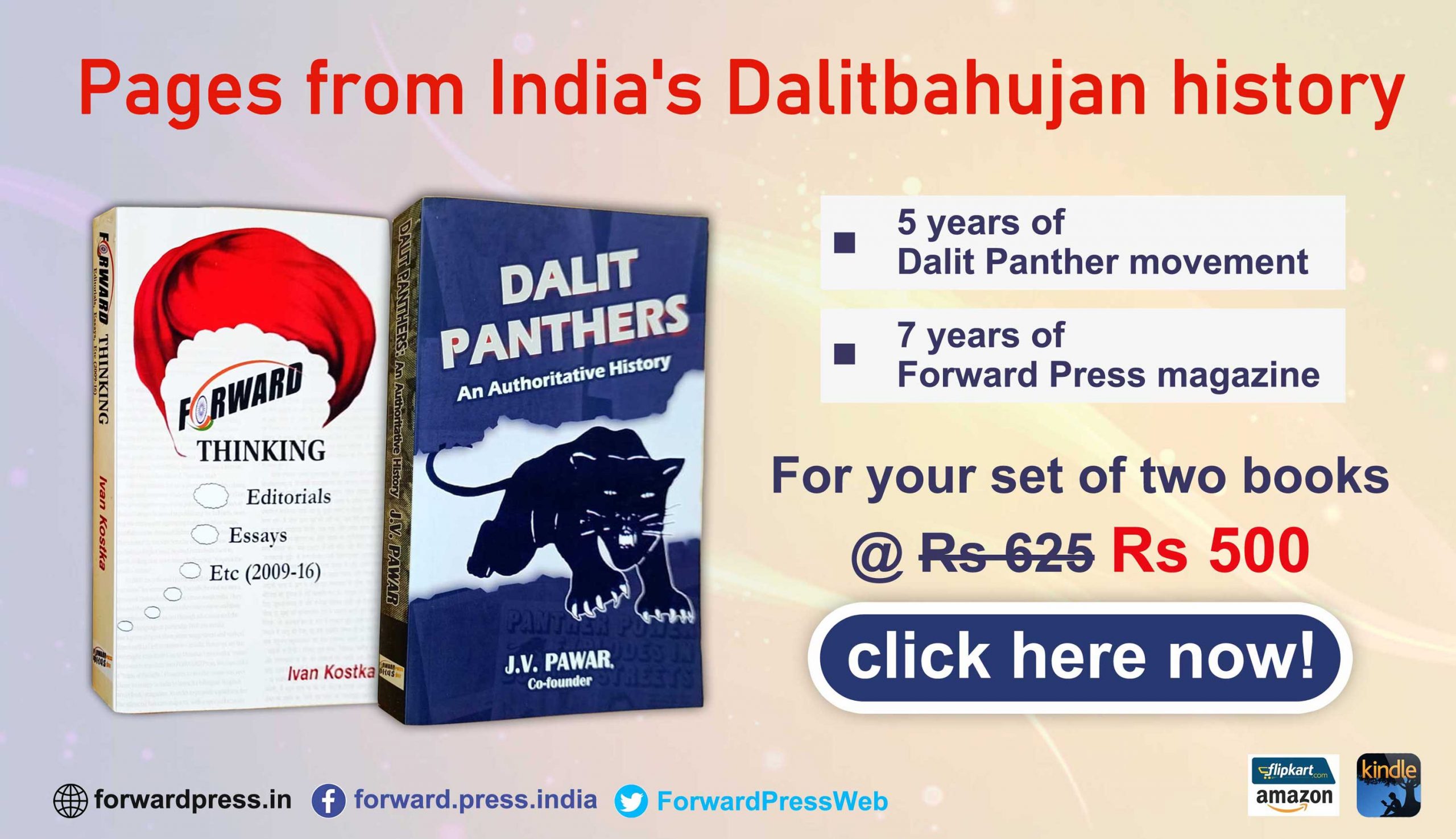

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History