Dahaad, a new web series available on the Amazon’s Prime Video platform, has been crafted by the notable filmmakers Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti. Ruchika Oberoi directed the series that was inspired by the real-life narrative surrounding Mohan Kumar Vivekanand, alias Cyanide Man. It encompasses a two-dimensional portrayal of the marginalized community, illustrating both the distressing circumstances they endure and their growing presence within the bureaucratic and administrative realms. It is also the first time that Rajasthan’s large Meghwal (Dalit) community has found a presence on the screen both as a protagonist and as a woman.

The Dahaad series depicts the complexities of the caste system. The villain, a serial killer, belongs to the Swarankar caste, which has been categorized as one of the Other Backward Classes (OBC) by both the State and the Centre. Anand Swarankar (played by Vijay Varma) is the son of an established jeweller. A majority of the 27 girls who are missing belong to Dalit and backward castes, points out Anjali Bhati, the Dalit sub-inspector investigating the case, while briefing her colleagues. Krishna Chandaal (SC), Fathima Lohar (OBC), Kiran Bairwa (SC), Meenu Bagri (SC), Rinku Bishnoi (OBC), Priya Balai (SC), Rani Damor (ST), Geeta Garasia (ST, categorized as a Vulnerable Tribe Group, VTG), Bharti Mali (OBC), Swati Bhambhi (SC) and Nutan Bagri (SC) are some of the names mentioned.

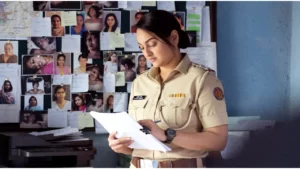

The scriptwriter perhaps needed to be as realistic as possible in finding a place for the Dalit woman protagonist in the police hierarchy of Mandawa, a small town in Rajasthan. Sub-inspector is as high up the hierarchy as they could go, and she reports to an inspector belonging to an ‘upper caste’. But if a Dalit woman sub-inspector is to be appreciated in Mandawa, only professional excellence will do. She is so engrossed in the case that she doesn’t even realize that she has worked 60 hours a stretch and has to be sent home by Inspector Devi Lal Singh to get some rest. Watching such scenes, it often feels like the responsibility for eliminating the caste system rests solely on the shoulders of Dalits.

The representation of a Swarankar as a criminal perpetrating crime against SC and OBC girls raises questions. While in a feudal state like Rajasthan, OBC communities have been known to commit atrocities against Dalits, serial killers could belong to any caste and commit crimes against anyone. However, the choice of a Swarankar as the villain may be a deliberate creative decision by the makers of this series. Apart from the fact that Swarnakars (goldsmiths) have access to cyanide (used in refining gold), this choice could potentially stem from considerations such as the relatively smaller population and limited political influence of the community. Portraying the major OBC castes or ‘upper castes’ as criminals could invite controversy and backlash, which could have negative repercussions for the show. Thus, the creators may have zeroed in on the Swarankar caste as a safe bet and not, for example, a Marwari who owned a jewellery shop and employed a goldsmith. The palatial property that Anand Swarankar’s father lived in could be more realistically owned by a Marwari businessman rather than a Swarankar today.

Anjali (the protagonist, played by Sonakshi Sinha) is a committed, well-trained, and meritorious sub-inspector. She is confident, progressive and does not believe in superstitions. She rides an Enfield Bullet, wears shades, and challenges misogynistic comments. She is a Dalit but has the ‘upper caste’ surname ‘Bhati’. Yet, in that small town, her Dalit background is known to everyone. A Thakur chieftain, whose daughter has eloped and gone missing, does not let her enter the house for an inspection. Even Anand Swarankar’s father objects to Anjali entering his mansion, in the presence of the inspector and her junior colleagues, after Anand becomes a suspect in the serial murders. Within her police station, constables belonging to various caste groups address her as “Bhati Sa”, a term associated with the Rajput community. The colleagues she works closely with are both Muslims, a techie called Kassim, and a constable called Mansur. Even one of her mentors is a retired Muslim IPS officer, Z. Ansari, now a professor of criminology. Perhaps, this alludes to the camaraderie between Muslims, especially the ‘lower castes’ among them, and Dalits. Another constable posted at the police station waves an incense stick every time she passes by. Thus, in a workplace, where everyone is aware of her caste identity and where everyone apart from her is a man, she has put in that extra effort to command respect.

She maintains a casual relationship with her boyfriend, meeting him discreetly at night, and doesn’t mind mentioning it to Inspector Devi Lal. She thus displays a level of confidence and ease with her sexuality. It is also a reflection of her agency and autonomy over her own body.

Anjali could represent the new modern ‘Dalit middle class’ that has benefited from the Constitutional commitment to liberty, equality, and fraternity. She knows the power of the Constitution and asserts it. She believes everyone in society shares equal status irrespective of their caste, class, religion, creed, and gender. Yet, her own mother is deeply traditional, mostly shown keeping herself busy with pujas and even seeking the services of a Brahmin priest, to find a boy of Anjali. Her father, an inspector in the Public Works Department (PWD), who is no more, was progressive, educated and knew the importance of educating his daughter. He knew how casteism could ruin the future of his daughter. As she recalls during a conversation with Inspector Devi Lal, her father taught her not to bow to anyone and have her own source of income. Incidentally, these are very attributes Devi Lal is trying to inculcate in her daughter despite staunch opposition from his own wife, perhaps inspired by Sub-Inspector Anjali Bhati. His wife fears her daughter would turn out like Anjali Bhati who still hasn’t found a boy to marry.

One notable aspect of this web series is the juxtaposition of arrogance and casteism with the liberal and progressive nature displayed by the union of ‘upper castes’, exemplified by Devi Lal Singh, Superintendent Police (SP) and the Sub-Inspector Parghi.

Anand Swarankar’s crimes come to light because a Dalit man musters the courage to report to the police station that her sister is missing. When the police station refuses to register his complaint, he is forced to seek help from a Hindutva political group, who are seeking to make ‘love jihad’ a political issue, and lie that his sister had eloped with a Muslim. This portrayal suggests that Dalits are used as tools and foot soldiers knowingly or unknowingly and end up bearing the brunt of Hindutva politics.

Thus, the filmmakers have expertly dealt with these social realities. Yet the ‘upper-caste gaze’ has not been completely done away with. For instance, Anjali is shown protesting when Anand Swarankar’s father objects to her inspecting his house but she doesn’t do so when the Thakur chieftain is hesitant about letting her enter his house and clearly brings up her caste while talking to Inspector Devi Lal. Also, was it necessary for Anjali’s father to have died of cancer? It somehow seems to needlessly accentuate the misery of a Dalit family.