“Under the system of Chaturvarnya, the Shudra is not only placed at the bottom of the gradation but he is subjected to innumerable ignominies and disabilities so as to prevent him from rising above the condition fixed for him by law. Indeed until the fifth Varna of the Untouchables came into being, the Shudras were in the eyes of the Hindus the lowest of the low. This shows the nature of what might be called the problem of the Shudras. If people have no idea of the magnitude of the problem it is because they have not cared to know what the population of the Shudras is. Unfortunately, the census does not show their population separately. But there is no doubt that excluding the Untouchables the Shudras form about 75 to 80 per cent of the population of Hindus.”

Thus writes Dr B.R. Ambedkar in his seminal work, Who Were the Shudras: How They Came to be the Fourth Varna in the Indo-Aryan Society (1946), where he situates the degraded socio-cultural position of the Shudras (almost all the individual caste groups known as Other Backward Classes (OBC) in constitutional parlance today as well as some others belong to this historical-social category mentioned in both historical and literary texts).

The Shudra-OBC problem

The central problem relating to the Shudra-OBC is reflected by their under-representation in the very body-politic of our national life: from the bureaucracy to academia, military to foreign service; judiciary to media. Ambedkar’s rough estimate of proportion of the Shudra-backward classes (the socially and educationally backward) in the population, a year before India’s independence, perhaps includes those Shudra caste groups who have not been categorized as OBC in the central government’s list so far, such as the Marathas, Jats, Patels, Kammas, Reddis, and Kapus, to name a few. Many of these social groups have made attempts through their socio-political mobilizations to be recognised as OBCs.

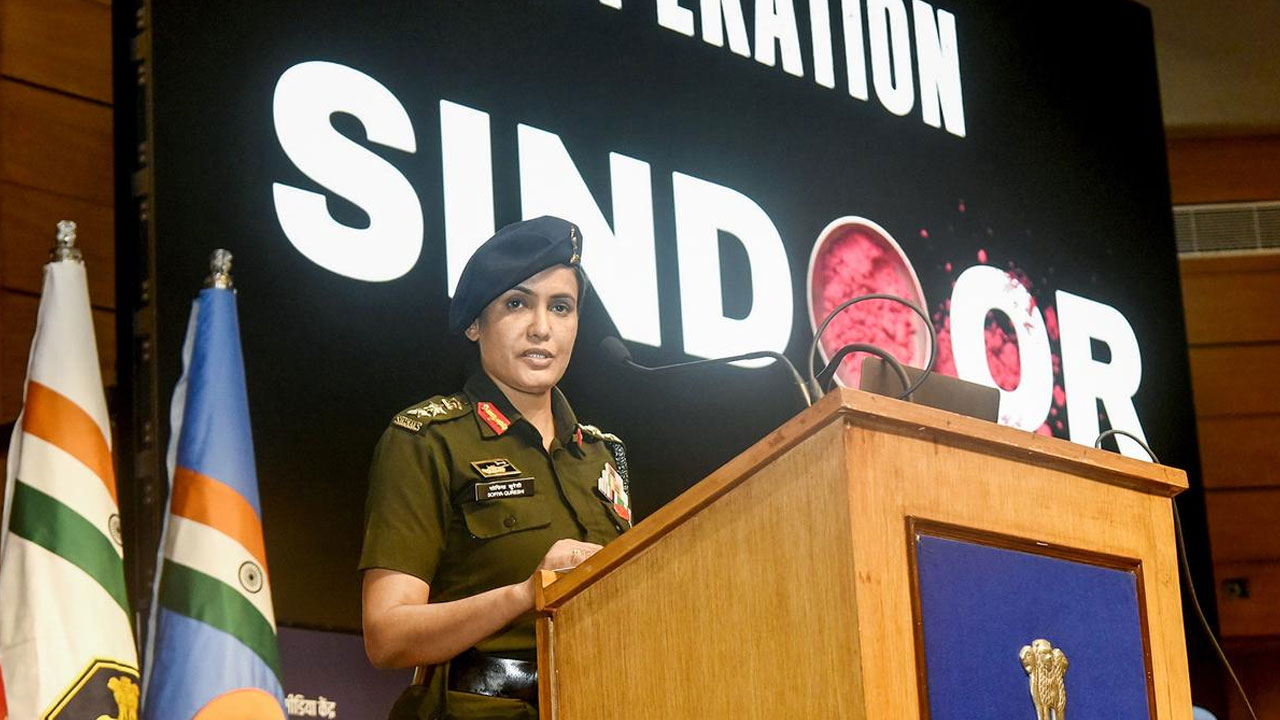

But a widely held estimate of Shudra-OBC population based on the Census of 1931, which was when the last time caste-wise data for all the caste groups was enumerated, puts it in excess of 60 per cent. The recently released report of the caste-based survey conducted by the Government of Bihar, led by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and Deputy Chief Minister Tejashwi Yadav, has validated the Samyukta Socialist Party’s clarion call of “picchda pawe sau me saath” (backward classes would seek 60 percent of their legitimate share) way back in the late 1960s. The Bihar government’s survey has revealed that 63 percent of its population – 27 percent OBC and 36 percent EBC – belongs to this mammoth category.

As most of us are aware, it was the British colonial administration that conducted the first census of the Indian subcontinent in 1881. It was primarily aimed at ascertaining the social, cultural, religious and linguistic demography to aid colonial governance. The unintended consequence of the exercise was an urge among sections of the populace for social justice. In the early 20th century, availability of caste-wise data played a crucial role in mobilization around the demand for representation of under-represented communities in education and employment.

Influenced by Jotirao Phule and his Satyashodhak movement, Shahuji Maharaj, the ruler of Kolhapur, introduced 50 percent reservation for the Shudras (backward classes) and Dalits (depressed classes) in educational institutions and government jobs as early as 1902 in the state. As noted sociologist G. Aloysius informs us, the Non-Brahmin movement in the princely state of Mysore had managed to win concessions in 1921 from the traditional oligarchy through recommendations of one Miller Committee, which can be understood as an earlier version of the Mandal Commission. Then in the 1920s, in Madras province, the movement led by Periyar succeeded in securing close-to-proportionate reservations for all sections of society, including 50 per cent reservation for ‘Non-Brahmin Hindus’ and Dalits.

After Independence, though, the Indian Republic came under the sway of dwija (twice-born) caste groups. They controlled both the legislature and executive (not to mention the judiciary) and steadily and purposely maintained a selective amnesia towards its Shudra-OBC citizenry as reflected in their casual approach to the setting up of the First Backward Classes Commission headed by Kaka Kalelkar, a Brahmin, and their unwillingness to count the OBC separately.

Twenty-five years later, the Second Backward Classes Commission constituted under the chairmanship of a former Bihar Chief Minister Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal submitted its report, which was partially implemented a decade later in 1990. Both the Mandal Commission report and the Bench comprising nine judges of the Supreme Court of India in their Indra Sawhney v/s Union of India (1992) judgment on the implementation of the report advocated a survey of all the caste groups in the country, in order to identify beyond any doubt, the actual number of the backward castes. Furthermore, this judgment had unambiguously underlined, “… what is unconstitutional with it, more so when caste occupation and social backwardness are clearly intertwined in our society?”

Not counting OBCs: A Nehruvian wrong or Modi impasse?

It is not surprising at all why the present central government led by a self-declared OBC, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, made a submission to the Supreme Court in September 2021 expressing its inability to count the Shudra-OBC caste groups. The affidavit submitted by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment read “the caste census for the Backward Classes is administratively difficult and cumbersome” and that this is being avoided as a “conscious policy decision since 1951”. This has exposed the real intentions and pretensions of the present regime towards the Shudra-OBC populace.

It is suggested that the present government arrived at such a categorical position against ascertaining the populations of the backward classes/castes based on the Cabinet decision of the Jawaharlal Nehru-led first government of independent India to conduct caste-specific enumerations of those who make up the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), since the policies were to be formulated for these specific groups in accordance with the special provisions mandated in the Indian Constitution. Although the Constitution did not automatically entitle Shudra-class/caste groups to such policies, Article 340 did say “The President may by order appoint a Commission consisting of such persons as he thinks fit to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes within the territory of India and the difficulties under which they labour and to make recommendations as to the steps that should be taken by the Union or any State to remove such difficulties and to improve their condition and as to the grants that should be made for the purpose by the Union or any State and the conditions subject to which such grants should be made, and the order appointing such Commission shall define the procedure to be followed by the Commission”.

True, the Nehru government did constitute the First Backward Classes Commission in 1953 and the commission submitted its report in 1955. But there was no alteration in the government’s policy towards the Backward Classes. Caste-specific issues of the vast majority of India’s population were swept under the carpet.

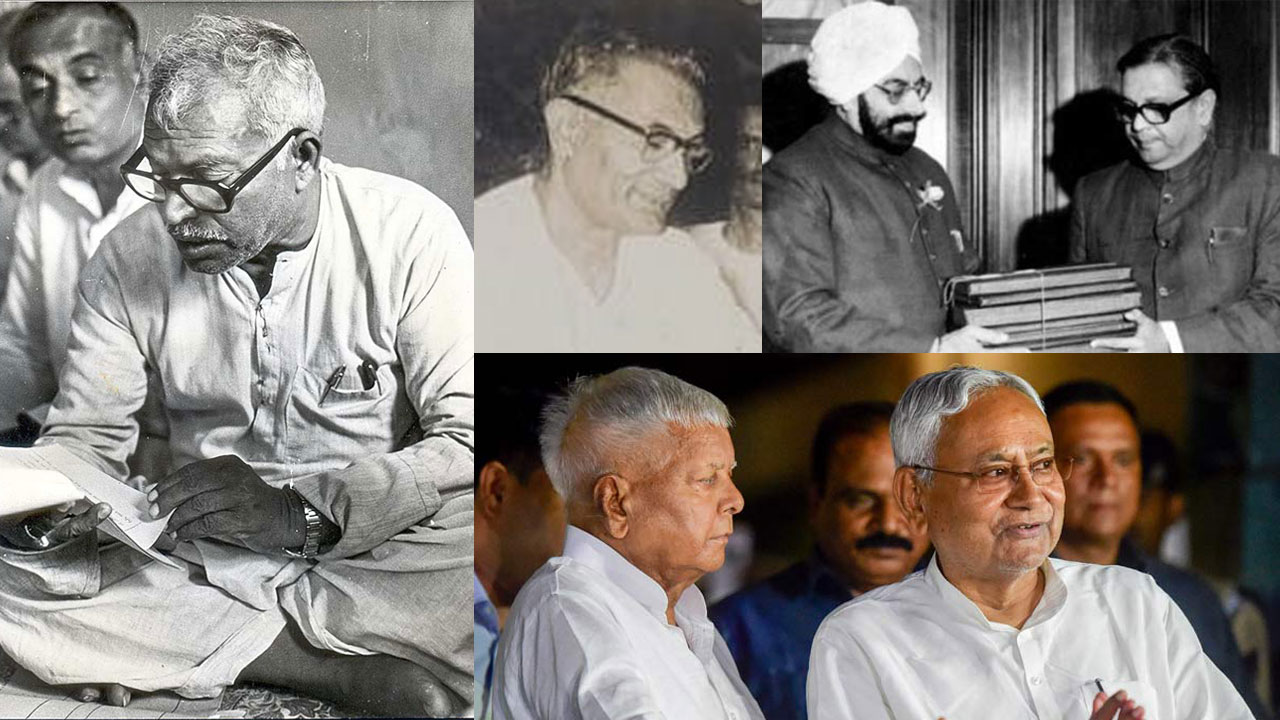

It was only leaders like Ram Manohar Lohia, Bhupendra Narayan Mandal, Karpoori Thakur and others who underlined the poor representation of the backward classes/castes in public life and hence pitched for their political mobilization under banner of a broad socialist ideology, consistently raising this question both inside and outside the parliament. In the pre-Independence Bombay and Madras presidencies, the Non-Brahmin Movements had already provided an early awakening of the Shudra-Backward Class consciousness; however, in the northern part of the country it was sharpened only with the socialist intervention post Independence.

Bihar model of social justice

Bihar witnessed its first Shudra-OBC upsurge electorally in the General Elections of 1967 when the mighty Congress Party suffered setbacks in several northern states. In 1968, Bindheshwari Prasad Mandal, who belonged to a backward caste, became the Chief Minister of Bihar who later went on to head the Second Backward Classes Commission during the Janata Party regime at the Centre. Sincere efforts at mobilization of the Backwards around issues that concerned them led to the Bhola Paswan Shastri government in Bihar constituting the Mungeri Lal Commission in 1971. The Commission submitted its report in 1976 identifying more than 120 caste groups as Backward Classes of which close to 100 were categorized as Extremely Backward Classes (EBC).

In 1977, Thakur became the chief minister of Bihar for the second time and in a year’s time he had implemented the recommendations of this commission. The same year India saw the first non-Congress coalition government at the Centre led by the Janata Party, which as promised in its manifesto, constituted the Second Backward Classes Commission headed by B.P. Mandal.

Though the Mandal Commission submitted its report to the then Indira-Gandhi led Congress government at the Centre in 1980, it looked destined for the fate of the Kalelkar Commission report. The political representation of the Shudra-OBC remained largely negligible till the movement demanding the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations raised consciousness about their electoral strength beginning with the 1989 parliamentary elections. It gathered further momentum with the announcement of 27 per cent reservations for OBCs in public employment, as recommended by the commission, by V.P. Singh-led United Front government in 1990.

This progressive move was vehemently opposed by the then principal opposition party, the Congress party led by Rajiv Gandhi. The Mandal mobilization led to democratization of Indian polity which drastically changed the demography of the elected representatives of India in less than a decade. Such a democratic upsurge was not considered even worth writing about, because university departments across the country were still monopolized by academics belonging to few privileged caste groups. Thankfully, Christophe Jaffrelot, a French scholar documented this upsurge and dubbed it as India’s Silent Revolution.

Earlier, the Bihar model of social justice had distinctly changed the perception of representative democracy by offering leadership to subaltern caste groups. India being a union of states, the chief ministers of the states play a key role in governance. The churning in Bihar resulted in the likes of Satish Prasad Singh, B.P. Mandal, Bhola Paswan Shastri, Daroga Prasad Rai, Karpoori Thakur and Ram Sundar Das becoming chief ministers in the pre-Mandal years. Lalu Prasad, Rabri Devi, Nitish Kumar and Jitan Ram Manjhi followed suit after the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s report. Three of these chief ministers were Dalits (SC) and the rest hailed from Shudra-OBC castes.

Under Nitish Kumar’s chief ministership, the Bihar government further extended reservation to OBCs and EBCs in local bodies and increased the cap for women reservation from 33 percent to 50 percent with quotas within the women’s quota for OBCs and EBCs in addition to those for SCs and STs.

The scenario, however, in Bihar’s neighbouring state, West Bengal, is harshly different. Bihar was carved out of the Bengal Presidency in 1912. West Bengal, which came into existence at the time of Independence, boasts to have witnessed a renaissance. Yet, it has had chief ministers belonging to only three upper-caste groups, Brahmin, Baidya and Kayastha, popularly known together as the Bhadralok in local parlance. All the chief ministers of the state so far bear privileged surnames like Ghosh, Roy, Sen, Mukherjee, Ray, Basu, Bhattacharya and Banerjee. While the proportion of Shudra-OBCs is still unknown, according to the 2011 census, 24 percent are Dalit and 29 percent Muslim. More than 90 percent of the Muslims are OBCs. It is ironic that West Bengal was ruled for 34 years by the Left Front government, which, ideologically speaking, was committed to bringing power to the so-called Chotolok (the proletariat).

The way forward

A recently published book titled The Shudras: Vision for a New Path (2021) has re-established how Shudra-OBCs have remained absent from major spheres of contemporary India, particularly the higher echelons of power involved in policy formulations and judicial interpretations. Among owners of media houses and journalists; justices of the High Courts and the Supreme Court; top bureaucrats, especially secretaries to various ministries; chairpersons of national institutions like University Grants Commission (UGC)/Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR)/Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR); and vice-chancellors of central universities or as directors of centrally funded institutions like IITs, IIMs or AIIMS, the OBC presence is negligible.

However, two major developments over the past month may give the social justice discourse in India a new tone. First, with the release of caste survey results by the Bihar government, claims and counter-claims of the OBC numbers in various states have begun. This includes states like Karnataka and Orissa. Some political parties have started promising similar surveys in the states if voted to power.

Second, the demand for “quota within (women’s) quota” for the OBC women was unequivocally raised by even those political parties like the Indian National Congress which have largely remained sceptical on the caste question and social justice. Other parties like the Apna Dal of Uttar Pradesh, even while remaining in alliance with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and having voted unconditionally in Parliament in favour of the Women’s reservation Bill, voiced support for the demand for quota within quota. For now, the 106th Constitutional Amendment Act (Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam) has provisions for reservation for women belonging to SCs and STs, but not for the OBCs.

Dr Ambedkar had once remarked, “We must not be content with mere political democracy. We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy.” Any imagination of a social democracy is premised on ensuring participation of the castes and communities excluded so far. There is an urgency, therefore, to come together to demand a caste-based decennial census that would ascertain the size and condition of each and every caste (not just the Shudra-OBC castes) in the population.

A 1931-like census might have the answers to at least four puzzling questions: One, does 10 per cent EWS (Economically Weaker Sections) reservation meant exclusively for the general category is logically sustainable based on their proportion in population? Two, isn’t there a robust logic for OBC quota within women’s quota since identities of caste and gender are intrinsically intertwined? Three, since the 50 percent cap on reservation has already been breached for implementing EWS quota, why can’t proportional representation be extended as has already been done in the case of Tamil Nadu? Four, is social exclusion of the Shudra-OBCs also manifested in their economic exclusion, signifying how “class” is mostly enveloped in “caste”?

Updated on 19 November 2024, 11.55 pm: It was the government led by Bhola Paswan Shastri (not Daroga Prasad Rai or Karpoori Thakur) that set up the commission under the chairmanship of Mungeri Lal in 1971 (not 1970).

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)