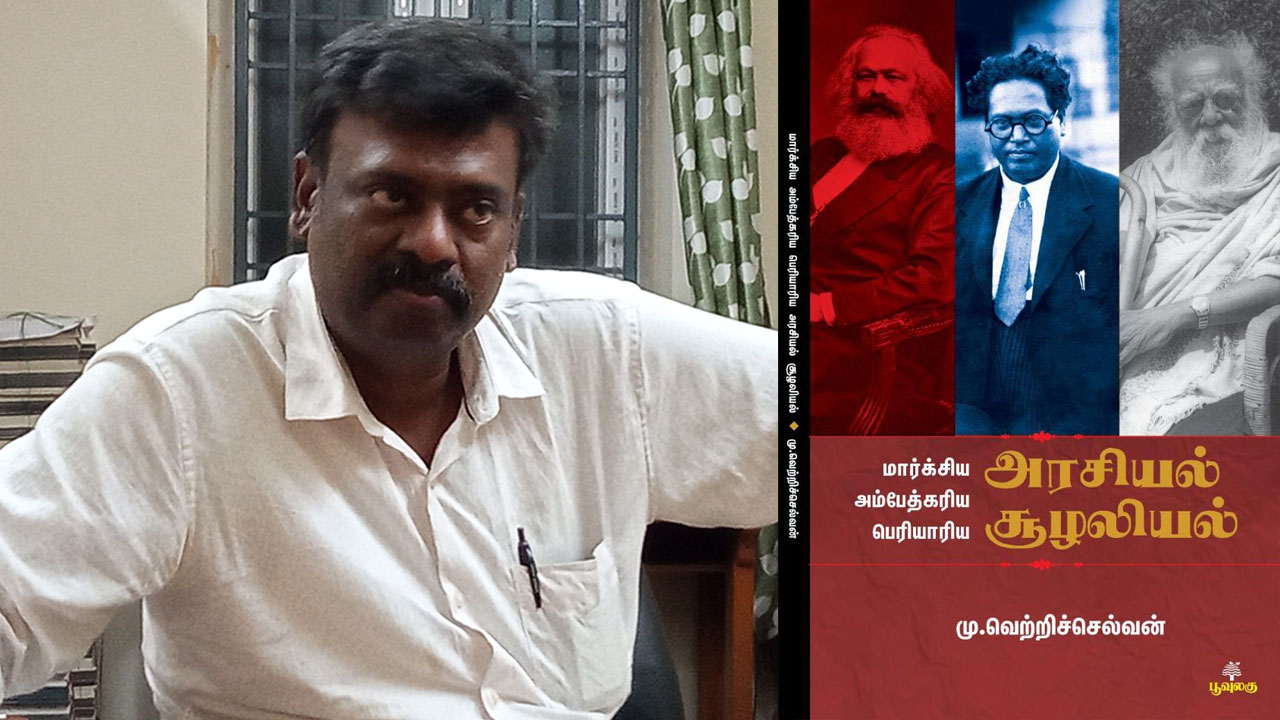

Advocate Vetriselvan is part of the organization Poovulagin Nanbargal, which for more than 30 years has been working for the cause of environmental justice in Tamil Nadu. Vetriselvan is a dedicated climate activist and has been writing and advocating for socio-environmental justice after completing his Masters in Law. His second book, on the legal battles against the Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant (whose title in Tamil translates to ‘Koodankulam: From High Court to Supreme Court’), was followed by a third on Marxist-Ambedkarite-Periyarite Ecology, titled Marxiya Ambedkariya Periyariya Suzhaliyal Arasiyal. This recently published work is unique in its idea and structure – it discusses environmentalism as a strong political ideology through lenses provided by the philosophies of Periyar, Ambedkar and Marx – and has been critically acclaimed by activists and scholars like Thol. Thirumavalavan (president of the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi), Advocate Arulmozhi (Periyarite Activist), and scholar and author V. Geetha. Vetriselvan talks to Athmanathan Indrajith:

Your second book was on the legal battle fought against the construction of the Nuclear Power Plant in Koodankulam. But your third book was on political ecology focusing on Marx, Ambedkar, and Periyar. Why did you choose to write on this topic?

As part of the legal team in Poovulagin Nanbargal, I felt the need for consolidation of the political parties and political organizations to get them to pursue environmental causes. I understood the ideological shortcoming because of which traditional Dravidian and Left movements were not taking up environmental issues. So, there is a lack of ideological understanding of environmental movements. While some of the postmodernist groups supported the environmental movements, Dalit parties were critical of such movements, which to them appeared as part of the feudal system and romanticization of the issues didn’t appeal to them. There were many criticisms of environmental movements, starting with the 2011 anti-nuclear Koodankulam struggle, sparking huge debates. A few progressive Left parties also criticized the anti-nuclear struggle in Koodankulam. At the same time, many Tamil nationalists, Periyarites, and Leftists supported this movement. When I saw these opposing stances within these ideologies, I thought of going back to the writings of the progenitors of these ideologies – Periyar, Ambedkar and Marx – to get a sense of their understanding of ecology. That’s how the third book evolved.

Periyar, Ambedkar and Marx figure in your book but Gandhi doesn’t. Why so?

This was not intentional. This is a state where Dravidian parties have been ruling continuously for 50 years. They have urbanized Tamil Nadu. So it was mostly the Dravidian ideology that had influenced the urbanization and industrialization process. So to have the thinking of Periyar on ecology is important. Periyar is considered as the ideologue, the father, of the Dravidian Movement. What is his thinking on ecology and on human development? That’s the key area. So to understand Periyar’s thinking on development, his progressiveness, his humanness, is essential. So I thought of examining Periyar’s thinking on ecology. I also wanted to examine the Marxist perspective on ecology. That was the time when the book “Marx’s Ecology” was released, which started new debates. Even with respect to the anti-nuclear struggles there were differences of opinion among the communist parties. I thought that it would be good to have both Marxist and Periyarite perspectives, as well as the Ambedkarite perspective. Environmentalism is part of Gandhism. There is more criticism from that perspective. But here, idealisms and ideas are in confrontation. Therefore, it makes sense that I examine Periyarite, Marxist and Ambedkarite perspectives before looking at Gandhi. I am writing on Gandhi. I would like to include the chapter on Gandhism in the future. In fact, one of the major critiques of the book was that this chapter was missing. We must have political ecology for a starting point. As far as Tamil Nadu or India is concerned or even in the case of global movements, I don’t think that we have political ecology as a separate school of thought. In my understanding you must have Periyarism, Ambedkarism and Marxism for political ecology. There must be a place for Gandhian thought and the ideas of Masanobu Fukuoka which are based on Zen and Buddhist thought. Now, I am trying to work on that aspect, too.

Today, we see Gandhi emerging as an important figure in political ecology while Ambedkar and Periyar aren’t talked about much. Why is this so? What is the primary difference between Gandhi’s perspective on the environment on one hand and Periyar and Ambedkar’s on the other?

That’s an important question. In fact, I have dealt with this question in one of my articles. Ambedkar was very critical of Gandhi’s natural green economy. In his book “What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables?” Ambedkar discusses many things, one of which is how the economic model hailed by Gandhi is trying to get us back to the old days, and has a feudalistic aspect to it. Gandhi used to say that we should go back to the village. Even Periyar was very much opposed to this idea of going back to villages. Periyar and Ambedkar considered the system and structure of the village as the basis for the evolution or the strong grip of caste – which is very much true. Because the layout of the entire village is based on caste. Different castes have their own streets. No part of the village will have a mixed-caste population. The entire village’s population is classified according to caste, and occupation is defined by caste, the basis for the division of labour is caste. Everything is controlled by caste, so the village plays a major role in protecting the caste-based system. So to abolish the caste system, to abolish Varna it is necessary to do away with the concept of the village. That is why Periyar was critical of the village setup and said villages should be destroyed in his book “Reformation of Villages”. Ambedkar said that urbanization, industrialization and mechanization would allow people leisure. The critique of Gandhi that urbanization and machines pollute the environment is an age-old complaint. Leo Tolstoy and others have also made these kinds of arguments. The problem is not with the urbanization or mechanization, the problem is with who controls the urbanization and mechanization. That is the point Ambedkar makes. So we have to resolve who controls these things and how to democratize. He was against a monopoly on urbanization or mechanization. So, he found that urbanization and mechanization helps people, but that the control on these processes should be democratized. He also held that only machines could let human beings have leisure and that every human being must have some rest and therefore every labourer must have some rest. In India, Dalits are a large group of labourers, they are supposed to carry out all menial work. So coming from that background and fighting for his people and seeking to be their voice, Ambedkar saw that the village economy would mean the continued exploitation of Dalits and the other marginalized communities. So to avoid exploitation, you need mechanization, you need urbanization and you need to get out of the village. So this is where Ambedkar was right on the mark. Gandhian philosophy was flawed in that respect. But coming to the matter of the environment, even in urbanized areas, Dalits live in spaces that are highly polluted, so even in urban areas, the right to a healthy environment is denied to them. So we have to address the question of environmental justice. That’s why we have to understand the perspective of Ambedkar. Gandhi’s philosophy was focused on the fight against colonialism, and hence his emphasis on a traditional economics represented by cotton-spinning and salt-making. Because he saw that these were the two areas in which the colonists were doing good business. So if you want to oppose the colonists, if you want to fight British imperialism, you have to fight the economic aspect of colonialism. Gandhi held the view that only a self-sufficient economy could help us here. That economy is available in our age-old practice, we have to get back our age-old economic practices. That is how we can fight the colonial system. Gandhi propagated the idea of a village-centric economy as a political tool to oppose British imperialism, which was in a way the right thing to do. Even today, to oppose the market economy, we, the left-wing and other progressive groups, support the localized production system, right? Even today we are saying small-scale industries must be supported. Gandhi had similar ideas. The problem is that the age-old economics is based on feudalism. Feudalism is based on the caste system. Unfortunately, Gandhi didn’t offer much criticism about the caste system. In the early stages of his political life, he was more of a Sanatana man. He supported the varna and caste system – although he opposed untouchability. Later, he may have had a different point of view. But he entered politics as a religious person and he considered the caste system as a part of human life. The problem is that it is not economics alone. It is about systematic control of the economy. A feudalistic economic system may be eco-friendly but it is anti-human. Whereas an urbanized, industry-centric economic system is pro-human in the sense that it gives liberty to choose your job and other things but it is an anti-ecology. So here, we have a new contradiction. Now how are we going to have an intermediate path? The solution will be an intermediate path. Yes, we have to abolish the feudal system, we have to abolish the caste system. So, it becomes necessary that we reform our village economy. Even Ambedkar in his election manifesto points out the necessity of reforming the villages, dividing land among its residents, including the Dalits, and empowering them and democratizing the village. This is one aspect. The other aspect is that we must have environmentally sustainable urbanization and development. In this way, the opposing views of Gandhi and Ambedkar helps us understand society in a larger sense and arrive at a solution.

In your book, you have written about Periyarite environmentalism. How is Periyar’s political philosophy of self-respect related to ecological conservation?

That’s an interesting one. When I started reading Periyar, I did not find anything related to ecology. Thereafter, having read many books on ecology and been involved in movements, I started re-reading Periyar. That gave me a new perspective. Having an ecological perspective and reading Periyar gives a new perspective. He was an unsophisticated, original thinker. He has written that he sees society in its own naked form – in its own natural form. That’s the key to a political understanding. If you want to work on ecological issues, you must understand nature at its own nature and the nature of human beings. Now the nature of human beings has been curtailed or changed or modified by the system artificially made by humankind. Rousseau was the first to critique this – where man is compelled to rein in his free will and to submit to society and behave in accordance with the rules and regulations created by the artificially made social systems. Thereafter, it was Hegel and Marx who gave the idea of alienation, in which the capitalist system alienates people – particularly the alienation of man from nature and man from man. Periyar says that both religion and nationalism alienates the natural perspective of man in India. Periyar wants a society in which human beings will be able to live with their natural essence. Periyar was influenced by Communist Society and the Soviet Union; his idealistic society is depicted in “Ini Varum Ulagam”. Reading Periyar makes us understand that he imagines a society where human beings are able to live with their natural instinct and consciousness. Similar to Marx and Hegel, Periyar was also dreaming of a communist society based on the very essence of humanness. In his own Self-Respect Movement declaration, Periyar makes the point that every natural resource will be for the people. That was one of the goals. He also argues that Man, including his rationality, his natural instinct, are curtailed by caste and nationalism. This is an ever-present undercurrent in his writings.

Gandhi and Nehru had their differences as the latter’s policies showed. You have argued that Periyar and Marx were environmentally conscious. Yet Tamil Nadu is beset with environmental problems, so is Marxist-ruled Kerala. Where do you think the contradiction lies? The parties in power have failed to translate ideology into action on the question of the environment.

Marx and Periyar did not concern themselves directly with the environment. They never talked about ecology and conservation directly. Philosophically, they analyzed in depth the nature of nature. They have analyzed what is the nature of society, what is the nature of man, and how man can protect himself. Marx’s concept of alienation – along with his “The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844” – was never discussed among the communist parties, saying that it was a young Marx who came up with the concept. They only accepted the later Marx and his “Capital”. Still today in Tamil Nadu, we don’t have a Tamil translation of “The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts”. The communist parties ignored the early works of Marx considering them merely idealistic and not materialistic. This criticism is wrong. Only human beings don’t feel part of nature, all other living things do. Marx notes even in “Capital” that human beings are the only living beings to pay rent to live on this planet. Even Periyar also had similar ideas and wanted to build a society based on human essence. Both were against monopolies. Both supported modernity but criticized a monopoly over modernity. Those belonging to the Dravidian Movement as well as the communist parties followed principles of modernity. They believed that advancement lay in modernity. Both communist parties and Dravidian parties were influenced by developments in the Soviet Union. It was only in the 1970s and 1980s that environmental movements evolved to question this pro-development stance. Before this, most of the “environmentalists” were feudals who supported a village-driven economy and ignored socio-economic questions.

When it comes to involvement of women in environmental movements, do you think these movements are inclusive because most of them are upper-caste women? What is your opinion on this?

Even environmental movements were supposed to be for the elite. The environmental work pertained to activities like preserving beaches, conservation of birds, and so on. It was not based on livelihood issues. The Chipko Movement and Narmada Bachao Andolan Movements were some examples of environmental movements that took up livelihood issues. There was a huge participation of women in these movements as well as in the Koodankulam struggles. The word ecofeminism was coined by Europeans. Women were leading the protests against nuclear energy. Unfortunately, ecofeminism has not developed materialistic or political critique on its own. In their book “Ecofeminism” Maria Miles and Vandana Shiva critique the capitalist and communist ideologies, saying that both have failed to understand ecology and are known for their rigid materialism. At the same time, the ecofeminism propagated by Vandana Shiva has some ingredients of romanticism and spirituality. Miles and Shiva suffer from the deficiency of turning the law of physics into a rare philosophy and of talking about nature in a spiritualistic way. Ecofeminism is a major school of thought and it must have its own evolution, its own political understanding. By romanticizing women as being central to agriculture, owning the land – these kinds of statements alone cannot define a new school of thought. You must have a political and societal understanding. In India, women were never given ownership of land. Prof Meera Nanda critiqued Miles and Shiva’s book, arguing that the postmodernist critique of society by ecofeminists is in a way supporting right-wing activism. By romanticizing agriculture and organic farming, we are in a way supporting the right-wing groups who take pride in the age-old systems. Ecofeminism must be based on rationality and on the laws of nature. At the same time, I also agree with some of the points of Vandana Shiva. We need to have a separate, detailed discussion on this subject.

You mentioned right-wing ideology. At a time when right-wing politics is on the rise in India, how do you think the challenges differ in the case of the environment?

The advancement of technology is leading us slowly towards surveillance capitalism. By controlling technology, they are able to control and manipulate large groups of people. Now we are having a State in which every person is developing a hyper-nationalistic personality. Any idea of making India a superpower must be seen critically. The idea of building nuclear power plants, atomic bombs, a large number of dams, large number of roadways and airports, and tallest buildings – these are the ways to achieve hyper-nationalism. They are emotionally attached to the idea, they are not intellectually driven to debate policies. The more emotionally attached they are, the less rationally they behave.

There is a huge wave of Green Capitalism in the world. Can capitalism and environmental conservation co-exist? If not, why not?

The very basis of capitalism is exploitation of nature. To make capital, you need raw material, which you have to extract from nature. At the heart of capitalism is profit. For profit, you have to produce. To make a profit on production, you must have consumers. For consumption of a product, consumerism has to be promoted. Then you have to do propaganda on that. Then you have to modify the system in accordance with propaganda and production. For that, you must have a State which supports the system. So you cannot have a solution within this system.

We live in a caste-ridden society. How will Marx be useful to us while dealing with environmental issues here?

Whether it is class, caste or any division, it alienates. Marx is the first person to have done a scientific analysis of alienation – how capitalist society alienates people from others. So, that must be the basis of tacking environmental issues from a Marxist perspective.

As you have said, Periyar and Ambedkar are on the same page on environmentalism with respect to the village economy. Is there any point where Marx, Periyar, and Ambedkar are on the same page on environmentalism?

Yes. They were all internationalists, having no boundaries. Their ideas were based on humanism. They wanted the entire human society to be together. They were not nationalistic. They were not linguistic. They believed all towns are one; all people are kith and kin. They aspired to be part of a democratic society, and also were very scientific. They were more materialistic, understanding society in its own natural form. These are the points which I have also made in my book.

How do you think political ecology became relevant in recent times? Particularly, as Chennai is experiencing floods once a year, posing a challenge to the disaster management systems …

Now a lot of people are talking about climate change. But initial floods did not trigger much discussion. Now, the chief minister, ministers, and a lot of people are talking about climate change. Because of the continuous work done by environmental movements, we have been able to convert ecological issues into electoral issues in Tamil Nadu. Ecological issues have played a major role in electoral politics – Sterlite, Koodankulam, Adani Port, are political, electoral in nature. In Tamil Nadu, the last ten years have seen a major breakthrough for political ecology.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)