Shankardas Kesarilal Shailendra (30 August 1923 – 14 December 1966)

“It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness,” wrote Marx, in the preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Shankardas Kesarilal Shailendra, one of the greatest lyricists of Indian cinema, was a testament to this Marxian dictum. His caste, class and ideological commitment defined the trajectory of his life and work.

What Shailendra wrote was a product of the material realities in which he was born. His consciousness was shaped against the backdrop of the horrific partition of India. Poverty inflicted by his Dalit identity had a lasting impact on his life. What others learn from theory, Shailendra learnt from life. He could convey deep philosophical messages in the common man’s language. He was a common man’s philosopher and an organic intellectual determined to serve the oppressed classes through his poetry. Shailendra is considered the “Kabir” of Indian cinema. His lyrics spoke of alienation, caste-class inequalities, systemic suppression and poverty that marked postcolonial India.

Shailendra was born in 1923 in Rawalpindi into a poor Dalit family at a time when feudal relations defined society. Living in dire material conditions, Shailendra, as a child, used to smoke beedis to suppress hunger. Along with his family, he moved from Rawalpindi to Mathura before the Partition. A major incident widely recounted about Shailendra is related to his being a brilliant hockey player. Once, in Mathura, after his team won a hockey match, casteist slurs were hurled at him by fellow players. Stung, he decided not to touch the hockey stick ever again in his life. The social exclusion that Shailendra inherited was his constant companion. His first job was as a welder with the Indian Railways in Matunga, Mumbai. Whenever he had some time to spare, he would visit the local IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association) office. IPTA has been the cultural front of the Communist Party of India. Association with IPTA introduced him to Marxism, which would later influence his writing. His poetry was inspired by the theory of class struggle and the prevalent systemic injustices. He would often recite political poems at IPTA gatherings. It was at one such event that he met Raj Kapoor. When Shailendra read his poem “Jalta hai Punjab”, Raj Kapoor was among the audience. Following the event, Raj Kapoor offered Shailendra the opportunity to write for his films but he refused. While this initial refusal emanated from Shailendra’s commitment to serve the interests of the working people and socialism, his economic condition would later force him to approach Raj Kapoor. Shailendra’s first assignment was film Barsaat (1949). This is how Shailendra stepped into Hindi cinema and how the famous collaboration of Shailendra and Raj Kapoor began.

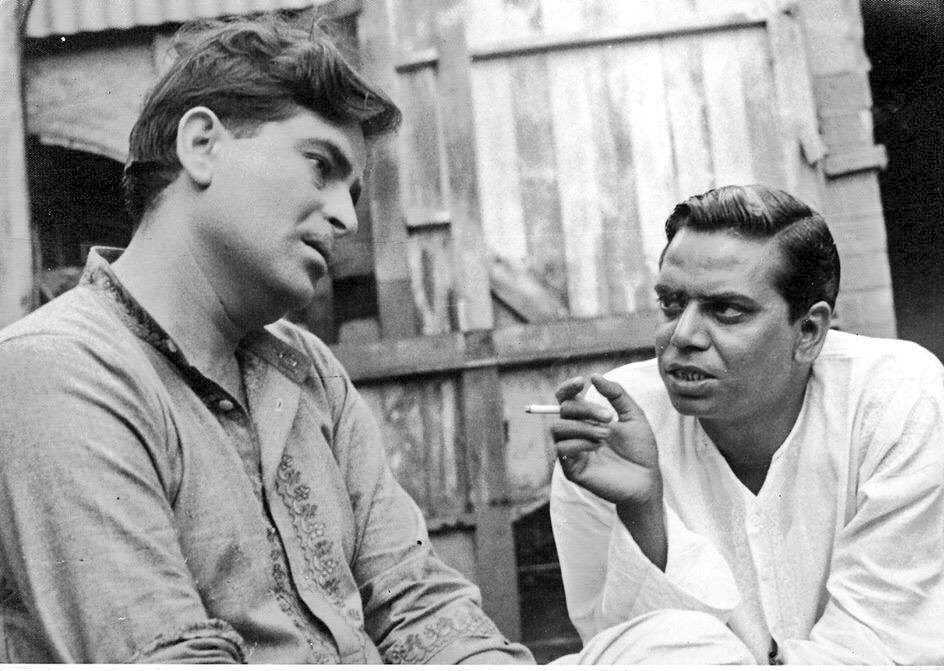

Kaviraj Shailendra

Raj Kapoor and Shailendra became close friends. Their director-lyricist bond was legendary. Raj Kapoor gave Shailendra the titles of “Pushkin” and “Kaviraj”. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Shailendra’s poetry was a major factor behind the success of Raj Kapoor films revolving around India’s social issues. The two songs from their first collaboration Barsaat mein Hum Se Mile tum and Patli Kamar hai were instant hits. However these songs did not reflect Shailendra’s Marxist consciousness.

The Raj Kapoor-Shailendra duo gave Hindi cinema several classics – Awaara (1951), Shree 420 (1955), Jagte Raho (1956), Anari (1959), Teesri Kasam (1966) and Mera Naam Joker (1970). These films became iconic because the common man could relate to their songs. Some of the iconic songs were Awaara Hoon, Ghar aya mera Pardesi, Mera Joota hai Japani, Pyar Hua Iqrar Hua, Ramaiya Vastavaiya, Zindagi Khwab hai, Kisi ki Muskurahaton pe ho Nisar, Sab Kuch Seekha Humne, Sajan Re Jhooth mat bolo and Jeena Yahan Marna Yahan. These songs were a stark commentary on society and class consciousness was central to them.

Shailendra went on to win three Filmfare Awards for Best Lyricist. These were for Yahudi, Anari and Brahmachari. Shailendra knew that he was addressing a society divided into classes and castes. Therefore, his songs talked about the broader solidarity among the oppressed masses. His identity, once the cause for his material deprivation, became an instrument for shaping the consciousness of the working class. Who can forget the songs of Boot Polish. The song Nanhe Munne Bacche was a critique of the class exploitation under Brahmanism and capitalism. Guide also achieved iconic status. Its songs symbolized resistance against an inhuman material world. Aaj Phir Jeene ki Tammana hai is a revolt against the patriarchal structures. Songs like Kaanto se Kheech ke ye Aanchal were a call for liberation of women from oppressive societal structures. Though all songs of Guide have social and political overtones, one of them, Wahan Kaun hai Tera, sung by S.D. Burman is deeply philosophical, too. Although many consider this song to be existentialist, it is actually more than just that. It is also a depiction of the alienation faced by an individual in a capitalist system.

Teesri Kasam

Teesri Kasam (1966), produced by Shailendra and directed by Basu Bhattacharya, starring Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman, is a cult classic and often a case study for students of art and culture. The film is considered significant for its lyrical depiction, poetic realism and storytelling. It won the National Film Award for the Best Feature Film. However, it was a commercial disaster and ruined Shailendra.

Teesri Kasam is an adaptation of Maare Gaye Gulfam, a short story by Phanishwar Nath Renu. It revolves around the characters Heeraman and Heerabai. Heeraman is a guileless bullock-cart driver while Heerabai is a “Nautanki” artist. Both are victims of feudal exploitation. Heeraman is underpaid and Heerabai’s body and art are considered a commodity. Shailendra gave the film his everything. Perhaps, he could identify with Heeraman and Heerabai. Teesri Kasam was a complete antithesis of commercial cinema. It was meant to disturb the masses unlike the romanticized depictions in commercial cinema. The film also took a toll on Shailendra. His colleagues deserted him and he was mired in debt. Excessive drinking and smoking hollowed him out. His letters to Phanishwar Nath Renu during that phase can move the reader to tears. A poet and lyricist who taught, in Gramsci’s words, “optimism of the will” to the masses through his slogans, Har Zor zulm ki Takkar mein, Hartal hamara Naara hai, himself lost hope. He taught the oppressed and socially excluded sections to live by the slogan Tu Zinda hai toh zindagi ki jeet par yakeen kar but he himself lost faith in struggle. Shailendra passed away in 1966, months after the release of the Teesri Kasam. He was only 43.

Shailendra preached what he inherited with his Dalit identity and what he imbibed with class consciousness and an ideological commitment to Marxism. Writing more than 800 songs in a span of 17 years is a majestic achievement. His pen laboured for the class interests of the working people and socially excluded sections. Who can forget the iconic lines from his song Nanhe Munne Bacche Teri Mutthi Mein Kya Hai in the film Boot Polish (1954):

Muthhi me hai taqdeer hamari,

Hum ne qismat ko bas mein kiya hai.

What Maxim Gorky is to the Soviet Union, Shailendra is to India. Their art shares a common ideology. Their political consciousness is still relevant for larger working-class solidarities. Gorky wrote novels to awaken the consciousness of the oppressed masses in Russia and the rest of the world. Shailendra wrote songs that sought to awaken the toiling masses to their potentialities.

Edited by Amrish Herdenia/Anil

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)