More often than not, Ramabai Ambedkar [Ramai] has been projected in cinema, serials, and literature as a weak, meek personality. Her immense sacrifices are acknowledged, but even here, the discussion is confined only to the level of a homemaker. In the general discourse, she is presented as an obedient housewife who contributed “indirectly” to the movement of Babasaheb by efficiently managing the affairs of home while Babasaheb was active in initiating the landmark emancipatory movement.

This is the impression that I get from her depiction in the so-called popular culture. To take just one example, is this not how she was presented in Jabbar Patel’s fascinating film Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar?

Is there any truth in the above-mentioned portrayal of Ramai? Was she just a dutiful housewife of Babasaheb, or was she an active co-emancipator who, like Babasaheb, envisioned a society free from man-made divisions and fought actively to achieve it? Before proceeding to answer these questions, I would like to first discuss how Babasaheb himself viewed the legacy of Ramai, for it enables us to get the right framework for assessment.

In 1941, Dr B.R. Ambedkar published his pathbreaking text titled Thoughts on Pakistan [later republished as Pakistan or Partition of India in 1945]. Written in response to the resolution passed by the Muslim League in 1940, Babasaheb’s book became a classic in no time. To quote his own words from the Preface of the same book:

“The book by its name might appear to deal only with the X. Y. Z. of Pakistan. It does more than that. It is an analytical presentation of Indian history and Indian politics in their communal aspects. As such, it is intended to explain the A. B. C. of Pakistan also. The book is more than a mere treatise on Pakistan. The material relating to Indian history and Indian politics contained in this book is so large and so varied that it might well be called Indian Political What is What.”

It was a significant intervention in the discourse of the time indeed and Babasaheb Ambedkar chose to dedicate it to none other than Ramabai:

“INSCRIBED TO THE MEMORY OF RAMU as a token of my appreciation of her goodness of heart, her nobility of mind and her purity of character and also for the cool fortitude and readiness to suffer along with me which she showed in those friendless days of want and worries which fell to our lot.”[1]

This article takes inspiration partly from the above dedication by Babasaheb for Ramai and partly from the fascinating inputs shared by my good friend J.S. Vinay, whose grandparents worked closely with Babasaheb and Ramai, and aims to throw light on the forgotten hands-on contributions of Ramai in social reform, along with a description of a few moments of her short life.

A brief introduction

Ramai was born in 1897. Their family hailed from the Dapoli region of Maharashtra. It has been said that she is related to Gopalbaba Walangakar, who was not only a havaldar in the Mahar Regiment but also a great associate of Mahatma Jotiba Phule[2]. Interestingly, Jotiba used to regularly deliver lectures – which also included excerpts from his books Gulamgiri (Slavery) and Shetkaryacha Asud (Cultivators Whipcord) – to soldiers of the Mahar Regiment in and around Poona[3]. It was probably during these meetings that Dr Ambedkar’s father, Ramji Maloji Ambedkar, met Jotiba, for whom he had immense respect[4].

After the death of Jotiba in 1890, Gopalbaba continued the movement of the Untouchables, and when the recruitment of Untouchables to the Indian Army was banned by the British, he worked tirelessly to get them to lift the ban. Dr Ambedkar’s father, who shared a good bond with Gopalbaba, was also involved in this movement.

It is possible that this friendship led Dr Ambedkar’s father to find a perfect match for his beloved son in Ramai. The young pair, Bhim and Ramabai, got married around 1907 in Bombay. They had a total of 5 children, of whom only their first son, Yeshwanth Bhimrao Ambedkar, survived [1912-1977]. The names of their four children who passed away were Gangadhar, Ramesh, Indu and Rajratna.

Sociopolitically active Ramai

J.S. Vinay recalls his grandparents telling him that it was Ramai who urged Babasaheb to build institutions for Dalits. “She had said our people should go to their own places to study rather than go far away. Maybe she could relate to the challenges with Babasaheb’s education …”

Ramai was actively involved in raising sociopolitical consciousness among the Untouchables. For instance, she played an instrumental role in managing the “Depressed Class Women’s Association.” As was reported in the Times of India in 1931 (and brought to my attention by Nikhil Bagade): “A meeting of women belonging to the Depressed Classes was held on Sunday at Poybawdi Improvement Trust’s Chawls. About 500 women including Mrs Ramabai Ambedkar, Mrs Venoobai Shivtarkar, Mrs Subhadrabai Anand Kassare, Miss Anusya Shivtarkar, Miss Janabi K. Chandorkar, Mrs Shivbai Gaikawad were present. Mrs. Savitribai Borade presided. The meeting resolved to form Depressed Class Women’s Association in Bombay … Resolutions to help and support the temple Satyagraha at Nasik, and to support Dr Ambedkar in his brave fight to secure political rights for them were passed”.[5]

Even before the formation of the Depressed Class Women’s Association, Ramai had been quite active in the social movement. We should not forget that Dr Ambedkar’s emancipatory movement from 1918 till 1935 (the year of Ramai’s passing) included pathbreaking initiatives like the formation of Bahishkrit Hitakarani Sabha (Society for the Uplift of the Depressed Classes), the launch of Mahad Satyagraha, legislative struggles with respect to the Watan Act, and so on, and Ramai likely had a fair share of intellectual and social contributions in the making of these movements.

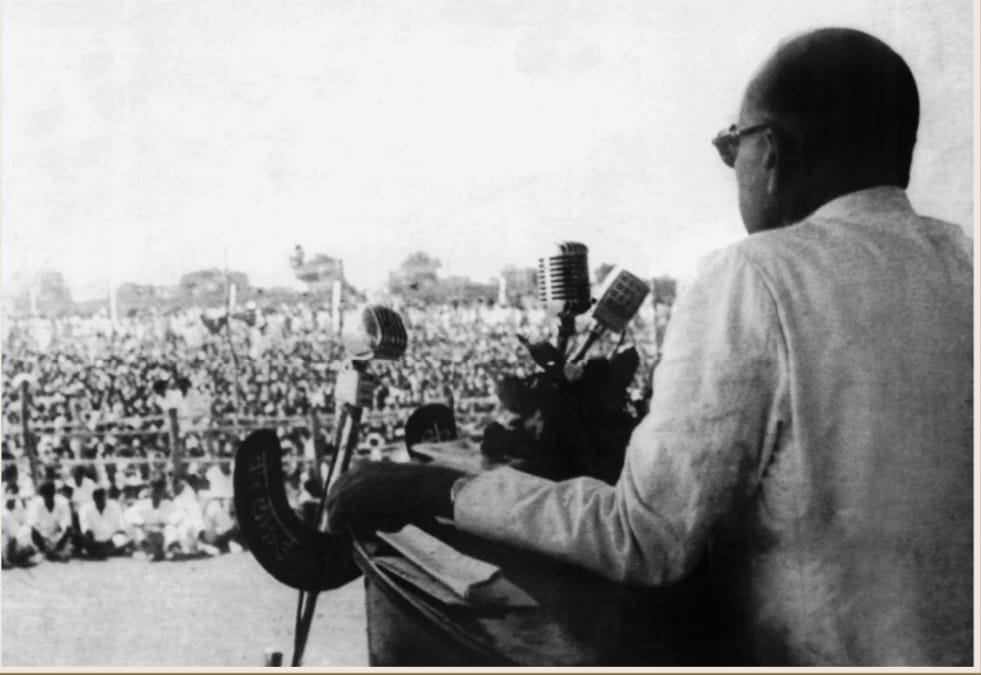

Dr Ambedkar had immense faith in the emancipatory role of women’s leadership of movements. and it is not a surprise that he walked the talk by inspiring and educating women belonging to marginalized castes to participate in socio-economic and political movements. A few years after Ramai’s passing, in 1942, he addressed more than 25,000 women at the All-India Depressed Classes Women’s Conference held in Nagpur in 1942:

“I am very happy to have this occasion of addressing you. There cannot be an occasion of greater happiness to anyone interested in the advancement of the Depressed Classes than to witness this gathering of women. That you would assemble in such vast number – almost 20,000 to 25,000 strong – would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. I am a great believer in Women’s organization. I know what they can do to improve the condition of society if they are convinced. In the eradication of social evils, they have rendered great services. I will testify to that from my own experience. Ever since I began to work among the Depressed Classes, I made it a point to carry women along with men. That is why you will see that our Conferences are always mixed Conferences. I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved, and when I see this assembly, I feel both convinced and happy that we have progressed.”[6]

The conference passed resolutions unanimously to demand abolition of polygamy, legal sanction to divorce, improvement of the economic conditions of women (with special focus on working class women, appointment of lady supervisors in mills), and representation of the women from Depressed Classes in provincial (state) and central legislatures. This is proof of the visionary, transformative and progressive politics of Dr Ambedkar at the time.

Ramai’s association with Dharwad

The Dharwad region became part of the Bombay Presidency in the early 1800s after the Anglo-Maratha wars, and in 1956, it became part of the then Mysore state (which, after 1973, came to be known as the state of Karnataka).

Dr Ambedkar seems to have visited Dharwad in the 1920s to get details about an Untouchable person who championed the cause of education for all classes in the 1850s. As has been succinctly recorded by N. Dinesh Nayak:

Dr Ambedkar’s tryst with Dharwad began in the 1920s when he discovered that it was an “untouchable” from the region, who was instrumental in securing admission for Dalit children in schools way back in 1856. When a school in Dharwad denied admission to the son of this person (referred to simply as “the Mahar from Dharwad” in Bombay government records) because of his caste, he approached the Bombay Native Education Society head, Edward Elphinston, who in turn forwarded his plea to East India Company. The British government subsequently issued orders allowing admission in its schools to all. … A curious Dr Ambedkar later came to Dharwad searching for that person’s family in 1927. Though he could not trace them, it cemented his connection with the city. The person Dr Ambedkar looked for remains unknown to this day.”

Later, Dr Ambedkar visited Dharwad along with Ramai to provide her a refreshing environment to convalesce. Within a short period of their arrival, Dr Ambedkar and Ramai established student hostels and co-operative and credit societies for the Untouchables. It is possible that these initiatives were their tribute to that unknown Untouchable who initiated the fight for human rights in Dharwad. As N. Dinesh Nayak noted:

In 1929, Dr Ambedkar and his wife not only lived here for a few months, but also made Dharwad the launching pad to expand his activities of Dalit amelioration in the south … One of the ventures started by Dr Ambedkar during his stay in Dharwad was the setting up of a cooperative society of Dalits. … Activist Lakshman Bakkai said the Machigar Cooperative Credit Society was set up by two of his followers — Parashuram N. Pawar and Yallappa Hongal — cobblers by profession. They are believed to have taken part in the historic Mahad Satyagraha, headed by Dr Ambedkar. Interestingly, the first members were all illiterate cobblers. But Dr Ambedkar infused in them courage and guided them. It was a big success and when the society moved to its own building, Dr Ambedkar came down to Dharwad to inaugurate it. … During his stay in the region, Dr Ambedkar encouraged Dalit youth in Dharwad and surrounding areas to pursue education. To help such students, he built the Depressed Classes Student’s Hostel at Koppadakeri here in 1929. Dr Ambedkar approached the district collector and obtained two acres of land for the purpose.”[7]

As Dr Ambedkar had become preoccupied with the work of the Round Table Conferences, he requested Ramai to return to Dharwad to improve her health and to manage the hostel at Dharwad. But, when Ramai visited Dharwad, she was deeply shocked to see the sorry state of the hostel that she had started along with Babasaheb. Deeply moved by the conditions of the students, she sold her gold ornaments and used the money to purchase all the essential items. She herself cooked food for the students. Ramai monitored all the activities of the hostel till her death in 1935. During her stay at Dharwad, despite her ill health, she participated in inter-caste dinners and other programmes that aimed to bring about unity among various castes of the Untouchable community.[8] That was the level of dedication, love and commitment that she had for the people from marginalized sections!

In this context, it is unforgivable that feminists and academic scholars have remained totally indifferent to these contributions made by Ramai. Far from acknowledging and cherishing her legacy and extraordinary agency, they have reinforced the dangerous narrative that she has always been a dutiful housewife and nothing more. They seem to be relying on the lies of Khairmode – who has written many volumes of disinformation on Dr Ambedkar – to bolster their malicious propaganda. Research scholars like Dr Bhagawan Dhande have exposed the lies peddled by Khairmode in their books like Babasahebaanchya Badnaamicha Mahaprakalp (‘The Mega Project to Defame Babasaheb’), yet the number of people citing Khairmode in their academic books is on the rise!

Death of children

As we saw in the beginning, Dr Ambedkar and Ramai had five children, of which only Yashwant Bhimrao Ambedkar (1912-1977) survived. The unfortunate deaths of their four children in quick succession scarred the couple deeply. In a letter written to Dattoba Pawar after the death of his last son, Babasaheb wrote: “There is no use pretending that I and my wife have recovered from the shock of my son’s death and I do not think that we ever shall. We have in all buried four precious children, 3 sons and a daughter, all sprightly, auspicious and handsome children. The thought of this is sufficiently crushing, let alone the future which would have been theirs if they had lived, we are living no doubt in the sense that days are passing over us as does the cloud.”

Quoting the profound words of Jesus Christ (from Matthew 5:13 in the Bible), Babasaheb continued: “With the loss of our kids the salt of our life is gone and as the Bible says, “Ye are the salt of the earth, if it leaveth the earth wherewith shall it be salted?” … I feel the truth of this every moment in my almost vacant and empty life. My last boy was a wonderful boy the like of whom I had seldom seen. With his passing away life to me is a garden full of weeds. But enough of this. I am too overcome to write anymore.”[9]

In this situation of unbearable grief, it was Ramai who consoled Babasaheb. In the words of J.S. Vinay, which could be the words of his grandparents:

“When Babasaheb’s son Rajratna passed away, he was in deep grief. He was very close to him. Ramai gave him confidence. She told him ‘Those who continue grieving cannot accomplish anything in life. It is better for the society you move out of this grief. … Ramai saw the death of 4 of her children. But she didn’t keep on grieving for them for a long time. She believed that her sorrow is lesser than that of the Untouchables and other women. She always stood with Babasaheb like a rock, like a partner… So Ramai is NOT just sacrifice. She is strength, she is partnership, she is a comrade, she is a social reformer!”

Violin, sweet paan and moments of joy

Vanaspati Durgat’s family originally belonged to modern-day Haryana. Owing to extreme poverty, they moved to Bombay in search of work. They worked in the homes of a few English people before becoming construction labourers. In the late 1920s, they were involved in building Dr Ambedkar’s home, which would be named Rajgruha, in Bombay. Vanaspati Durgat was only 12 years old at the time. As Ramai loved children, she bestowed Vanaspati with abundant love, and naturally the young girl became close to her. Vanaspati recalled her memories of Ramai:

“I stayed with Ramabai most of the time. She had a habit of chewing paan and kept a silver case. Seeing her chew, I asked her for paan but she refused, saying, ‘Pori tu lahan aahe aajun. Sagde data kidhul jaat’ [You are too young. All your teeth will fall out].”[10]

As she hung around at Rajgruha with Ramai, Vanaspati would run into Babasaheb too: “He [Babasaheb] barely spoke to me. But he always asked me, ‘How are you?’ He patted me on my cheek and head before leaving home … In those days he was learning the violin in his gallery. I really liked the music so one day I started dancing to the tune. Ramabai found it amusing and ever since then it became a habit.”

Amidst their hectic schedule, Dr Ambedkar and Ramai would take out time to relax. In 1927, the couple watched Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a movie on slavery in the United States.[11]

What would Babasaheb and Ramai have discussed after watching the movie? Given the fact that Dr Ambedkar saw this movie in 1927, nearly a decade after his stay in New York, would he have described to her the struggles of African Americans as he witnessed them in New York in particular and America in general? Did they draw any parallels between the conditions of the Black Americans and that of the Untouchables? Unfortunately, there is no record of any discussions that may have ensued.

To the uninitiated, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is a popular novel written by White American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. There is no dearth of people who would place this text on a pedestal for inspiring Americans to fight against slavery. It has been said that when Abraham Lincoln gave an audience to Harriet Beecher Stowe, he is reported to have greeted her by saying, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war” [that is, Civil War (1861-1865)].

On the other hand, thinkers and writers of the Black community have criticized the text. Nobel laureate Toni Morrison has said that the text romanticizes slavery and presents it in an agreeable form to the white audience. She writes, “Harriet Beecher Stowe did not write Uncle Tom’s Cabin for Tom, Aunt Chloe, or any black people to read. Her contemporary readership was white people, those who needed, wanted, or could relish the romance.”[12]

Abraham Lincoln, too, has a fair share of critics. As an intellectual who has thoroughly studied the whole question of Black emancipation, Dr Ambedkar has a powerful take on the “real motives” of President Lincoln on ending slavery. Babasaheb begins by quoting the following reply given by Lincoln to Horace Greele in 1862:

“My paramount object is to save the Union, and not either to save or to destroy slavery … If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it. If I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it – and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

Having quoted the reply of Lincoln, Babasaheb makes this observation:

“These were the views of President Lincoln about Negro slavery and its relation to the question of Union. They certainly throw a very different light on one who is reputed to be the liberator of the Negroes. As a matter of fact, he did not believe in the emancipation of the Negroes as a categorical imperative. Obviously, the author of the famous Gettysburg oration about Government of the people, by the people and for the people would not have minded if his statement had taken the shape of government of the black people by the white people and for the white people provided there was union.”[13]

Cool fortitude

Dr Ambedkar once noted that he was the “most hated man in India” and that casteists consider him as “a snake in their garden”. As Babasaheb dared to challenge and attack the very foundations of the caste system and the religious sanction attached to it, he attracted an unmitigated degree of wrath from the caste society. A litany of letters were written to threaten from time to time. When Ramai was alive, the intensity of these threats and imprecations increased at the height of Poona Pact discussions. Perhaps, Ambedkar was recalling the “cool fortitude” – or profound emotional intelligence – she displayed in those circumstances.

Ramai’s death

On 19 April 1935, Dr Ambedkar was appointed principal of the Government Law College, Bombay. This was a remarkable achievement for a barrister who faced innumerable challenges in his law practice owing to caste discrimination. This appointment was also undoubtedly a powerful testament to the tremendous intellect and growing force of Dr Ambedkar as an authority of Law and Constitution.

But, within a month of his appointment, Babasaheb faced a terrible blow as Ramai passed away after a prolonged illness on 27 May 1935. Countless people from marginalized sections and friends of Dr Ambedkar from social movements and the Bar reached the residence of Dr Ambedkar to pay the final tributes to Ramai.

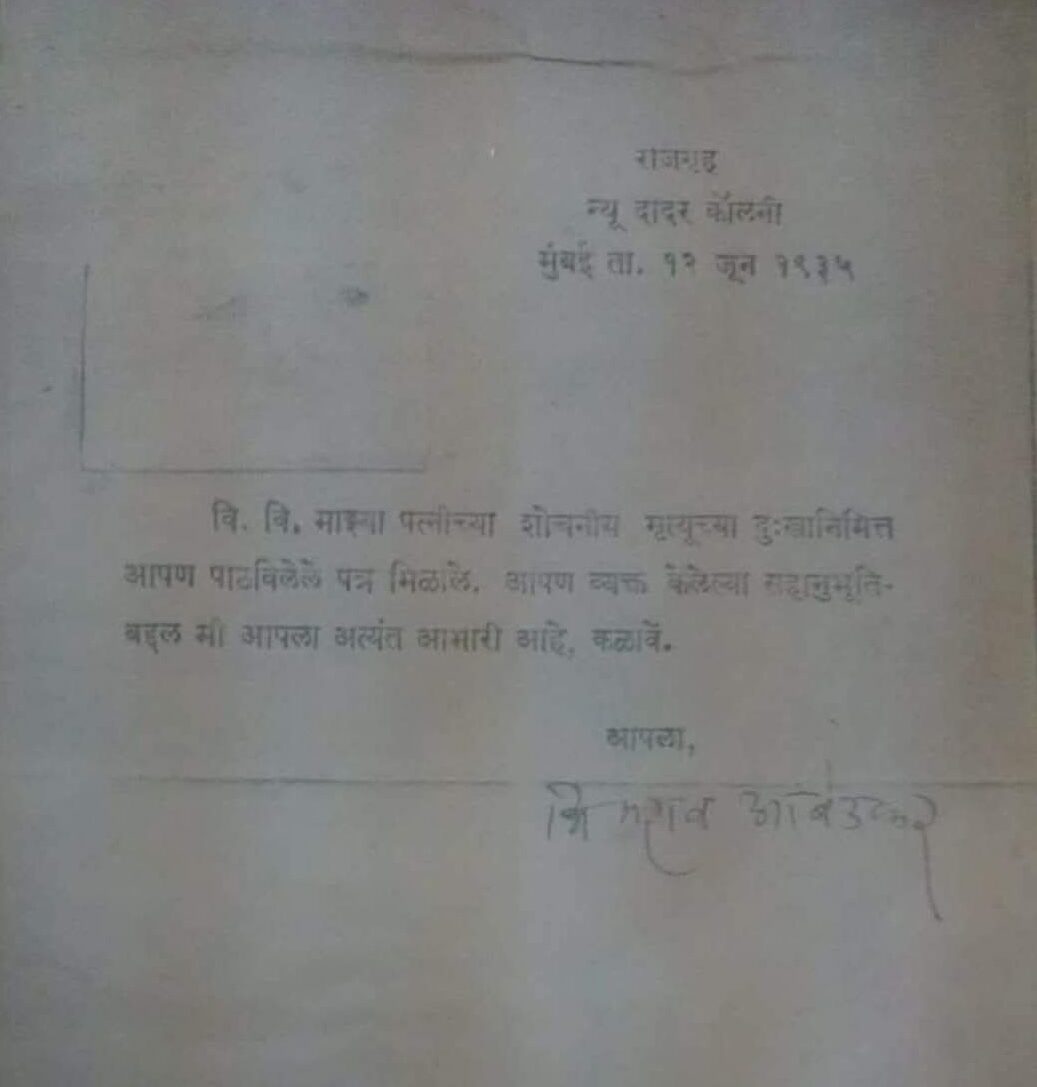

Quoting from a letter of Babasaheb that he possesses (see below), my friend J.S. Vinay observes:

“He [Dr Ambedkar] was very considerate to thank everyone personally who sent condolence messages to him on her death. In one of the letters, Babasaheb wrote: ‘I received your condolence letter on the lamentable death of my wife. I wish to let you know that I am extremely indebted for the sympathy you showed on me’.”[14]

Writing about the Ramabai’s passing, Dr Savita Ambedkar noted:

“Dr Ambedkar was struck by another calamity in the year 1935: on 27 May, his wife Ramabai passed away after a prolonged illness … Ramabai had been bedridden for many months with tuberculosis. Dr Ambedkar got several expert doctors to treat her, but she never recovered. This tragic incident left a deep impact on Dr Ambedkar. He started living a solitary life. Even before Ramabai died, he had lost four children – three boys and a girl. With his wife too dying in 1935, Dr Ambedkar never enjoyed domestic well-being and happiness. From 1935 onwards, he lived a solitary life. Till the time I entered his life, he did not have a single person with whom he enjoyed any degree of intimacy. In Delhi too he was a loner.”[15]

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Dr Ambedkar could never recover from the loss of Ramai. There were many instances where he would sob remembering her. In this connection, the reminiscences of Dr Namdeo Nimgade about Dr Ambedkar are worth quoting. Given the fact that the information also deals with the topic of marriage, children, and the responsibilities of the community, I take the liberty to share the quote to its fullest extent. Dr Nimgade recalls:

“The introduction of my son to Babasaheb was not as idyllic. Hira and I brought our son to Babasaheb’s house where we laid him at the great man’s feet. Babasaheb stared at the baby and then said: ‘You just got married and now you bear your child like a trophy that you have won. Now what will happen to your future education? You have fallen into the same trap as everyone else from our community. You study just a little, get a small job, and then settle down. Don’t you know how long it takes to rear a child? You have to spend all day with the baby, you have to play with the baby in the morning, then rush to work, then rush back and again attend to the baby. How will our community ever … At this moment I earnestly promised Babasaheb, ‘I will always try to obtain further education. It is my highest aim in life now. I named my son Bhimrao so that until my death I will always have your name on my tongue’.”

Quoting the reply of Babasaheb, Dr Nimgade writes:

“Overseas, people will be ready for their children with clothes and sweaters even before birth. Here, because of poverty, we cannot take care of our children even after birth. Let me share my own experience. I have myself suffered many years in poverty. Even after returning from overseas with a legal degree, I had difficulty practicing law because of caste discrimination. Because of my financial struggles I used to eat just broken rice and grew weak. One of my own children died of illness. I was too weak to even bury him. All that I had to wear were my suits brought from overseas, and those were woollen (and too hot for India). My legal practice slowly improved but then fate struck another blow: my wife Rama became grievously ill. The doctor warned that if she had another child she would surely die. To keep her alive, then, we maintained celibacy.”

Babasaheb became lost in his reminiscences. “‘She was so frail. I did everything in my power to save her; we used all sorts of pills and injections. I spared no efforts. Yet she slipped away from this earth. She left me.’ His voice caught, and then a tear fell from his eye. He cried almost like a child. At this sight, everyone in the room started crying. I had never seen even a tear from him before …

“The man who fought like a lion with political opponents to protect his oppressed people was now silently human … helpless as he remembered his late wife … I was astounded now in our private setting as I looked upon Babasaheb and realized the deep love he must have had for her. With heavy hearts we returned home.”[16]

That was Dr Ambedkar’s unfathomable love for Ramai! She didn’t live long enough to see the epic transformation of Dr Ambedkar from a humble boy residing in a chawl of Bombay city to the chief architect of the Constitution of India, who has single-handedly converted more than 10,00,000 people [ten lakhs!] to Buddhism in a span of two days – a remarkable feat that no religious founder or prophet in the entire history could ever achieve.

I remember, there were few instances where even Dr Ambedkar – the greatest champion of women in India – was not spared by the so-called feminists on social media, who have accused him wrongly of keeping his wife deliberately uneducated and confining her to their home. This propaganda can now be confined to the dustbin.

To conclude, let us stop confining the legacy of Ramai only to the realm of sacrifice and acknowledge and be inspired by her noble traits and remarkable contributions to the social movement.

References

[1] https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_08/pdf/22

[2] K.N. Kadam, ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and the Significance of his Movement: A Chronology’, Sangam Books, 1991

[3] Rosalind O’Hanlon, ‘Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India’, Cambridge University Press, 1985

[4] K.N. Kadam, ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and the Significance of his Movement: A Chronology’, Sangam Books, 1991; Also see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cRzcvCxt3o where I dealt with the connection between Jotiba Phule and Dr Ambedkar [along with Maharaja Sayajirao Gaikwad] in detail.

[5] ‘The Times of India’, October 26, 1931 (I thank my friend Nikhil Bagade for sharing this valuable information)

[6] https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_17_03/pdf/306

[7] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/following-babasahebs-footprints-in-dharwad/article7101462.ece#google_vignette

[8] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/dharwad-to-celebrate-its-connection-with-ambedkar-on-his-birthday-in-april/article69140254.ece

[9] See Prof Sunita Sawarkar’s article “Streeyanche Preranastaan: Ramai” in Sakal, 26 January 2014 (I thank my friend Milind Patil for the translation)

[10] https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/babasaheb-played-the-violin-i-danced-childhood-memories-at-86/

[11] See my article for the list of all the movies watched by Babasaheb Ambedkar, and the film, theatre and music personalities who interacted with him https://www.theculturecafe.in/p/an-unexplored-side-of-dr-ambedkar

[12] Toni Morrison. ‘The Origin of Others’, The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2016

[13] https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_09/pdf/300 – this link also contains the comparison that Dr Ambedkar made between President Lincoln and Gandhi as to how the former fared better than the latter.

[14] Letter written to V.V. (June, 1935)

[15] Savita Ambedkar, Babasaheb: My Life with Dr Ambedkar, Penguin, 2024

[16] Namdeo Nimgade, ‘In the Tiger’s Shadow: The Autobiography of an Ambedkarite’, Navayana, 2011

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in