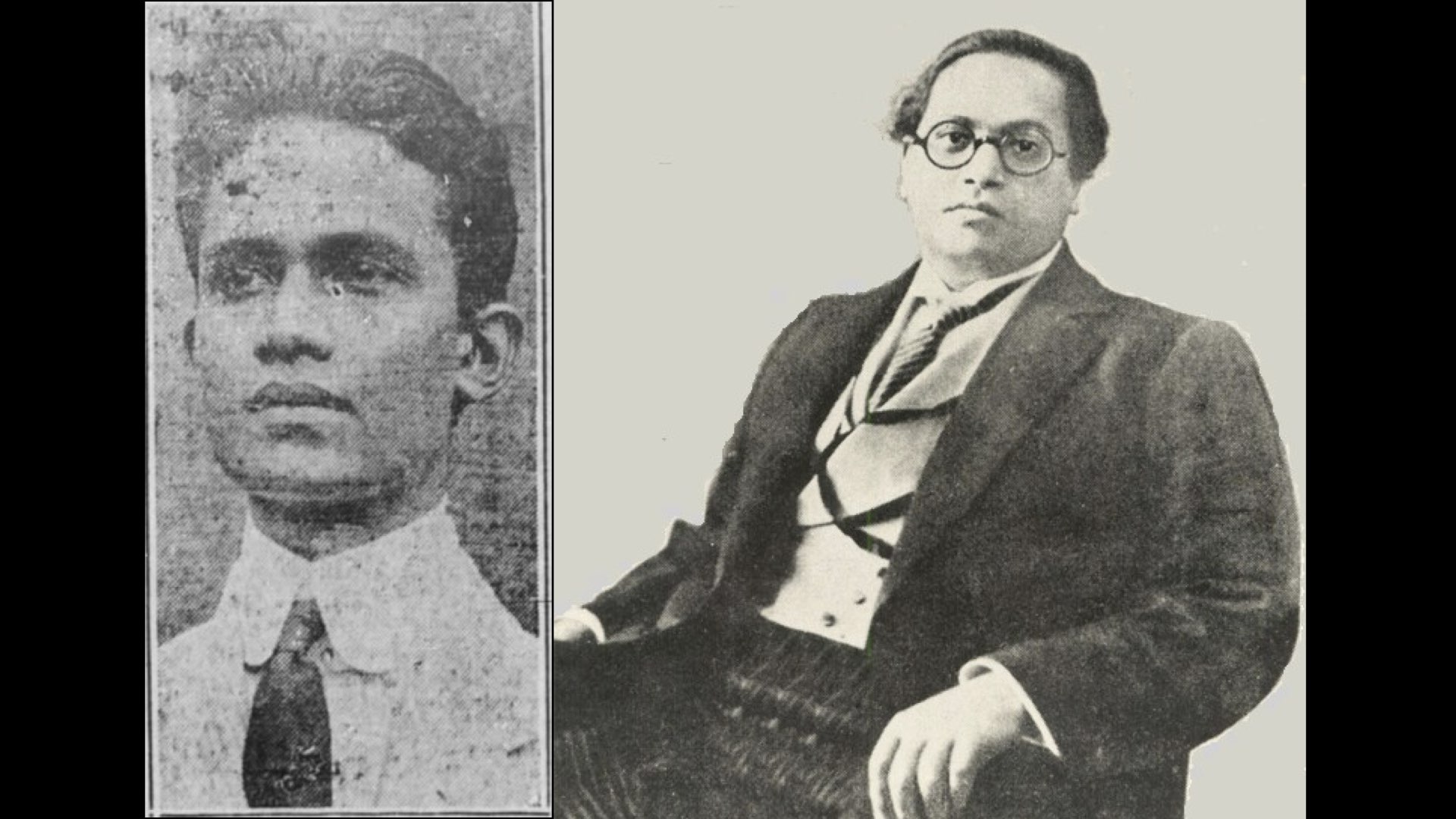

[This is my fourth article in a series I intend to write on the many events of Dr Ambedkar’s life that had been forgotten, erased, neglected, and perhaps even thought to be lost if not unknown. The only way to salvage any information, however small, about them was to go back and dig into the archives, conduct fresh investigation and find better primary sources that are dispassionate, and ironically sometimes quite unrelated to him, where he left his mark. I strongly believe that there is still a great deal to be found out and written about Dr Ambedkar. This short article is of one such event that made the news back when he had just earned Master’s degree (majoring in Economics) at Columbia University on 2 June 1915[1] at the young age of 24.]

Dr Ambedkar’s views on Indian trade and commerce, both domestic and international, which as an economist he had developed by reflecting on his training at Columbia, and the principles he espoused through his many writings and authorship of the Constitution of India are quite well known[2]. It acquires a whole Part (XIII) in the Indian Constitution running from Article 301 to 307. His vision was to stabilize economies through currency, labour rights, central banking concepts, industrialization, to name a few. It was a subject that was very dear to him. He had approached Baroda’s Sayajirao Gaekwad Maharaj about studying it and gone on to write several books on it (and forewords/prefaces to books written on the topic by others). He kept revising those texts amid his extremely busy schedule and commitments. Many of his public lectures that he gave on the topic in Bombay soon after his return to India are now probably lost[3]. In fact, his thesis for his Master’s degree was on commerce in ancient India. Dr Ambedkar studied economics and such subjects, not merely for fanciful lectures that he could deliver, but for being able to frame meaningful and beneficial actions through it. He was no believer in mere words. His objective was always principled and thoughtful action. With that in mind, it would be quite helpful to know what could have been one of his very first efforts, soon after he earned his first degree abroad, and before even resolving to venture into writing his second thesis for M.A., “National Dividend of India: A Historic and Analytical Study” which was lost unfortunately. This new archival material dates to a period of his life abroad that we know little about, so its importance cannot be understated.

The economy of America in the early 1900s was fairly strong, yet unstable at times. Huge corporations such as U.S. Steel, Anaconda Copper and by then defunct Standard Oil had already revolutionized the economy. Its economy witnessed a brief, but serious, panic in 1907 due to a collapse of trust companies leading to mass withdrawals of funds. The famous banker, J. P. Morgan, then aged 70, saved the day by bringing together all the bankers to his library and having them sign agreements and pool funds, arranging emergency loans, personally overlooking such institutions that he believed were worth saving, while dissolving the others, instilling a sense of confidence in the markets. In some ways this led to the formation of the Federal Reserve itself, while the economy came out stronger – for most people anyway. Come 1914, the Great War (First World War) eclipsed another financial collapse because of which the latter is rarely spoken about. By mid-1915, the Federal Reserve was only learning to walk as it was barely 2 years old, so the banking system was weakly regulated.

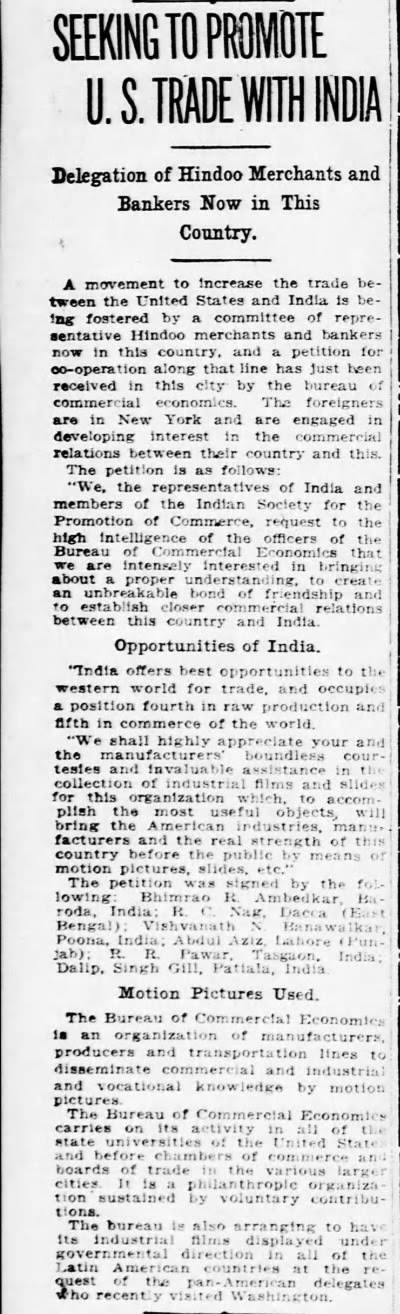

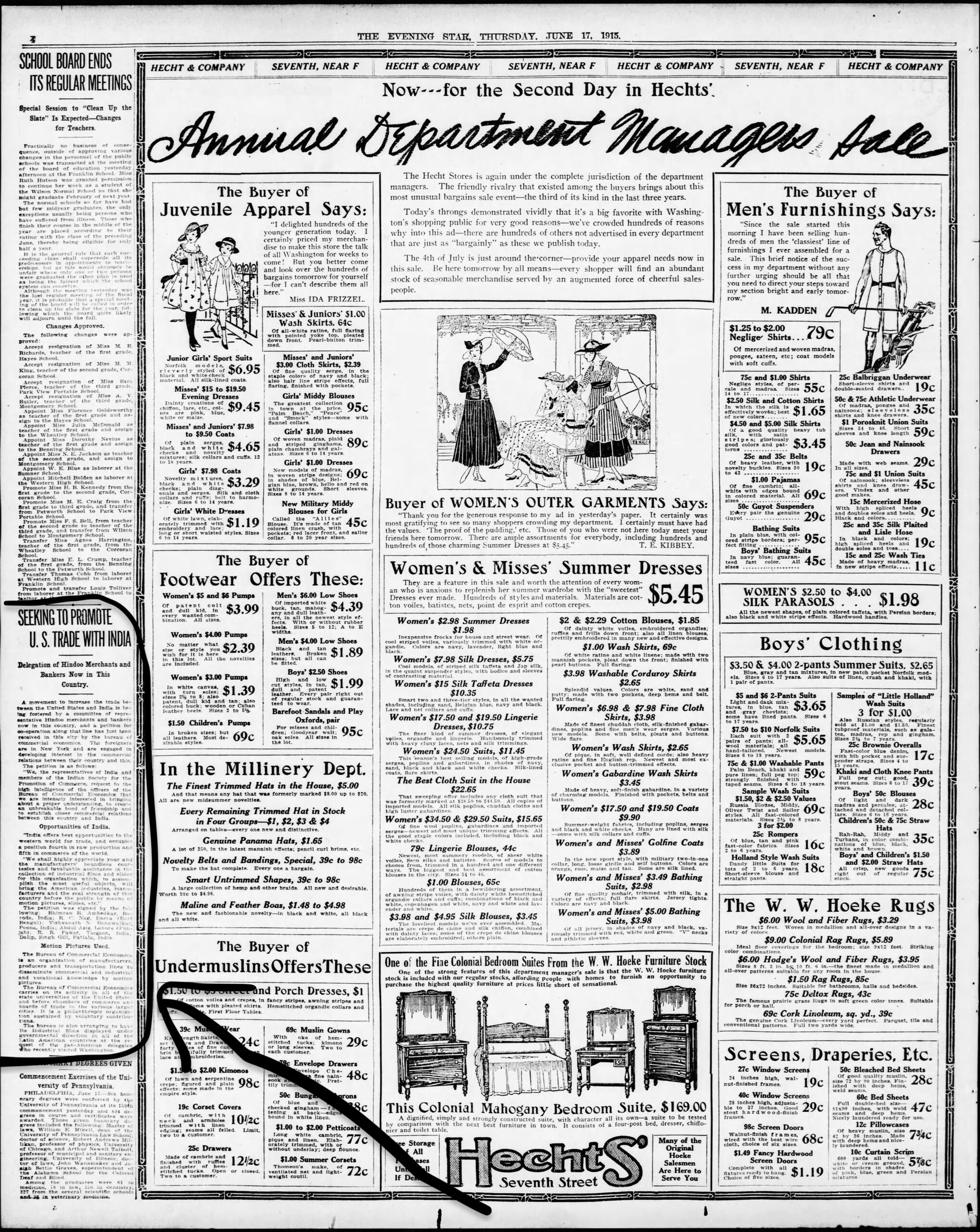

So, it happened that in June 1915, “a delegation of Hindoo merchants and bankers” found themselves in New York in order to improve trade relations with the US. As part of that effort, they signed a petition addressed to the Bureau of Commercial Economics that was “an association of the leading institutions, manufacturers, producers and transportation lines in this country [United States of America] and abroad to engage in disseminating industrial and vocational information by the graphic method of motion pictures upon the recommendation of the leading educators of the country.”[4]

This philanthropic, non-governmental, non-profit, that was only founded in 1913 by a nearly blind engineer supported by an economist, didn’t charge a cent for its work (being its only pre-condition), sustaining itself on voluntary contributions, through various “endowment funds and annuities”, and was initially headquartered in Philadelphia in the state of Pennsylvania (later moved to Washington). The organization had the cooperation of several Universities from the east coast to the west coast and several companies, such as John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil (now Exxonmobil), DuPont, Eastman Kodak, Hudson Motors (later Chrysler), Lipton and Ford Motor, contributing to the education drive through “motographs or slides”[5].

This group of the so-called “Hindoo merchants and bankers,” that included Dr Ambedkar, among other signatories, had signed the following petition, apparently reproduced verbatim in ‘The Evening Star’, urging to establish commercial relations between the countries:

“We, the representatives of India and members of the Indian Society for the Promotion of Commerce, request to the high-intelligence of the officers of the Bureau of Commercial Economics that we are intensely interested in bringing about a proper understanding, to create an unbreakable bond of friendship and to establish closer commercial relations between this country and India.”

The petition continued by pitching India as being a centre for trade opportunities, leading in raw production and commerce, and requesting industrial films for educating the public back home about the American industries’ strength.

“India offers best opportunities to the western world for trade, and occupies a position fourth in raw production and fifth in commerce of the world.

“We shall highly appreciate your and the manufacturer’s boundless courtesies and invaluable assistance in the collection of industrial films and slides for this organization which, to accomplish the most useful objects, will bring the American industries manufacturers and the real strength of this country before the public by means of motion pictures, slides, etc.”

“The petition was signed by the following: Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, Baroda, India; R. C. Nag, Dacca (East Bengal); Vishvanath N. Banawalkar, Poona, India; Abdul Aziz, Lahore (Punjab); R. R. Pawar, Tasgaon, India; Dalip Singh Gill, Patiala, India.”

Even though there is little information in this extremely important article, there are a few things to unpack here. Apart from Dr Ambedkar, who were the other people? They are not straightforwardly identifiable. What were these organizations? What happened to this petition? I hope to answer some of these questions in the rest of the article, before venturing to talk a little bit about the Bevin Scheme of the UK.

Let us deal with the people first and in the same order that the article lists them. Our first subject would be R. C. Nag, hailing from Dacca (present-day Dhaka) in East Bengal. He could be identified as Robindra Chandra Nag, apparently a friend of then recent winner of Nobel Prize (1913), Rabindranath Tagore, as per the papers from those times. He was a Columbia graduate of 1918[6] and a student at the University of Minnesota (Social Sciences and Politics) by 1920 when he reminisced about his youth in Calcutta (he served in the Calcutta Volunteer Rifles and, after graduating from the University of Calcutta, travelled with his aunt Mrs S. Banerjee, a high-caste-Hindu-turned-Christian preacher, to the US) and Texas[7]. His father “had the triple distinction of being Prince, Prime Minister and judge in India” serving in the British Government for 38 years; he was a judge in Bengal and Maharajah of Udaipur. A brother of Robindra’s was a Chief Justice and Maharaja of Jhind. Another brother was a senior medical student at University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Suffice to say, he came from a well-established family.

The second person on the list was Vishvanath N. Banawalkar from Poona (present-day Pune), where the initial stood for ‘Narayan’. He was a graduate from Columbia, too. It is possible that later in September 1918 he was even drafted for military service during The Great War from the town of Cambridge in New York under Major General Enoch Crowder.

The third person was Abdul Aziz from Lahore (Punjab), and although there is no reference to him that can be found in the papers or the Alumni Register, there is only one piece of coincidental, and rather circumstantial, information: He was Dr Ambedkar’s housemate who had appeared in the New York 1915 Census just about two weeks before this event. More information about this individual may be found in a previous article of mine[8]. To put it briefly, he was a 26-year old non-working person (but not a student) who had been in the US for four years by then.

The fourth person was R. R. Pawar from Tasgaon (now in Sangli district, Maharashtra). His full name might be Ramchandra Raoji Pawar. He was interestingly listed in the Columbia Alumni Register to have been from Baroda instead. Perhaps, that explains why more details about this individual could also be found in the Baroda State’s archived files at the Pune’s Gokhale Institute[9] that describes him as having been funded by the State to complete the degrees of BA, LLB, and a course of Economics and Commerce in New York. Later, he obtained the degree of MAAM. He had returned to India in August 1917, the same year mentioned in the Columbia Register. He was also reported to be working for the Revenue Department of Baroda and as a “personal emissary of the Gaekwar of Baroda”. In June 1914, he had arrived in New York, and visited Dayton (Ohio) as he was “making a study of municipal government in the United States” to help the Maharaja “to reorganize the government of cities in the state of Baroda”[10]. The seeds sown by Sayajirao Gaekwad (Gaekwar) Maharaj went deep and wide and India is yet to realize it, let alone acknowledge it.

The fifth and the last person listed in the article was Dalip Singh Gill, hailing from Patiala (Punjab) and son of a Sikh chieftain, often addressed with the title Sardar, which he had dropped for “democratic reasons”, when he came to the US. According to the Columbia Alumni Registry, he was a 1914 graduate from Columbia and was awarded a degree in Civil Engineering from its School of Engineering in the year 1916[11]. Perhaps, his background in engineering qualified him to sign this petition that dealt with education on industries. Around that time, aside from the fact that he signed this petition, he delivered a popular speech on “The Position of Women in India” for the General Federation magazine, admitting the lack of education among most Indian women. He cited poverty as the major cause and drew a comparison between Northern and Southern India. He noted that children in Southern India were actually married off early and forced to bear the burdens of motherhood at a tender age while in Northern India children were engaged early but the actual wedding and consummation didn’t happen until much later. During the First World War, he was “an observer in Germany and Russia and became intimately acquainted with General Ludendorf … since the close of the war … touring Europe and America for the government of Afghanistan”. As part of the tour, in 1925, he delivered a now-famous lecture called “Freedom for India” in which he also called for support for China’s freedom struggle.

Thus, the members of the group, including Dr Ambedkar, were young, outspoken and highly educated, their common aim being raising India’s position as America’s trading partner. Since we have already dealt with the Bureau of Commercial Economics in the beginning of the article, we can now talk a little bit about the “Indian Society for the Promotion of Commerce.” Unfortunately, I have not found any information about this organization so far. But what is clear is that it was some kind of an interest group of Dr Ambedkar[12] and other graduates from Columbia, with two members primarily being funded by Sayajirao Maharaj of Baroda. The only well-established commercial organizations in those times, based on my investigation, were the Indian Merchants’ Chamber (established 1907) of Purushottam Thakurdas and the Bengal Chamber of Commerce & Industry (established 1853). But they would have preferred to publicize their own name had Ambedkar’s group represented them. So, we can rule them out. This petition was by all accounts an independent venture.

Perhaps, more investigation needs to be carried out in other archives, especially that of the bureau itself, which have been quite difficult to locate despite it having played such a silent yet revolutionary role in mass education. Following a digital trail can only take one so far. Since I couldn’t trace the later history and ceasing of the operations of the Bureau of Commercial Economics, it was difficult to say as to what happened to it or this petition. There are brief mentions of the organization in the papers until the late 1940s and even 1950s. But what is indisputable is that by 1923 itself, within eight years of this petition, the Bureau of Commercial Economics had distributed film reels in India, too[13]. Later, the Bureau of Commercial Economics was to hold the largest film collection in the world, managing to screen films about human nature, human societies, natural wonders to people living on rivers, in icy Siberian regions and such remotest of the places of the planet that had never even seen a photograph.

Bevin Scheme

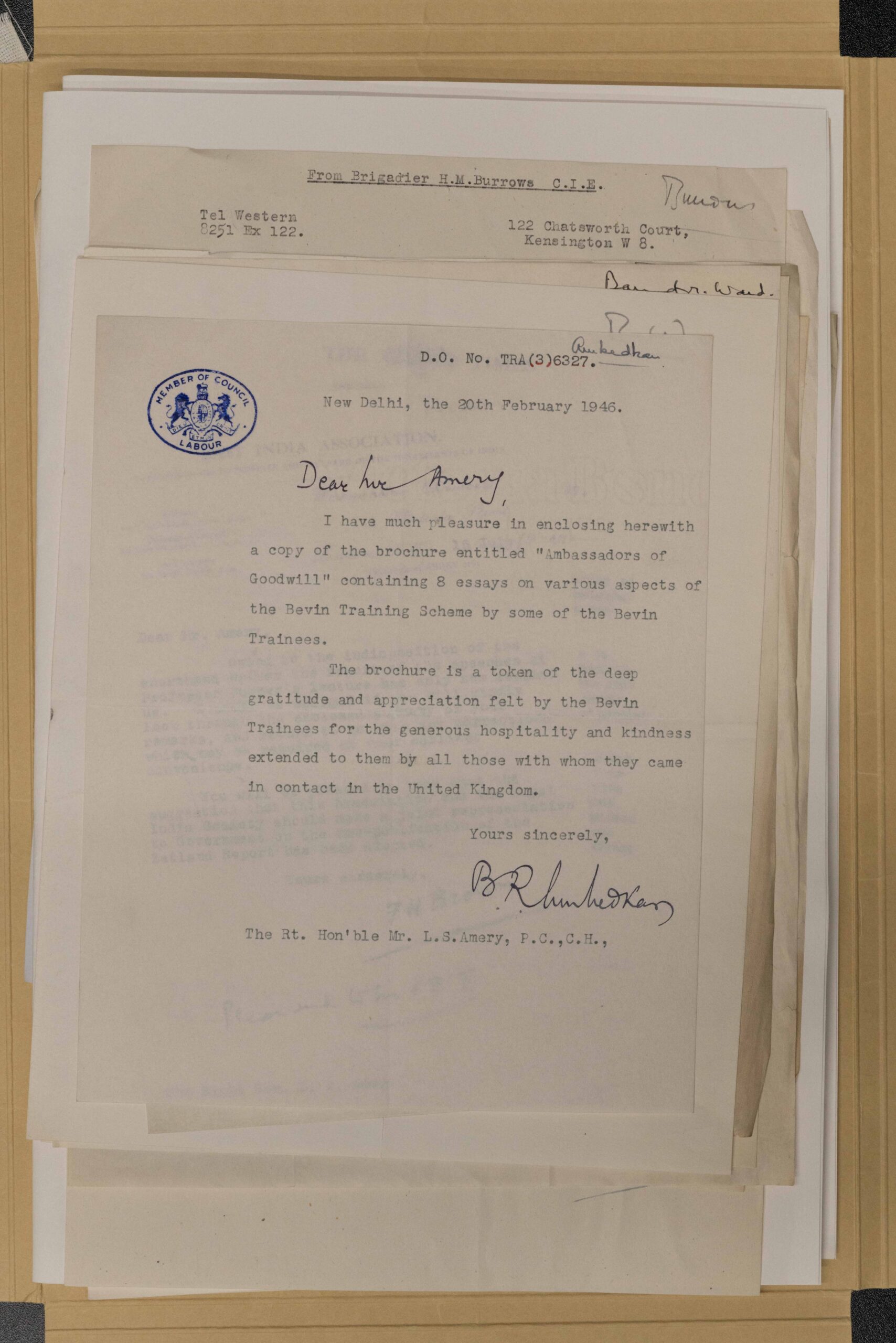

Dr Ambedkar, as an economist, studying under some of the best economists ever, realized the importance industrialization, trade and commerce held for any country, and especially a country like India. He also understood the importance of films in mass education and in this case, technical training. In the later part of his life, when the opportunity arose, Dr Ambedkar, as Labour Minister, ensured the participation of members of the backward classes and scheduled castes to get training in Britain. Ernest Bevin was the Labour Minister in the British Government and in late November 1940, devised a plan with the then Secretary of State for India (Mr Amery) for “bring[ing] several hundred Indians from workshops in their country to this country [UK] to be trained to live in the homes of our people. After this they will be sent back again with the knowledge of trade unionism and other organisations in this country … This is a great precedent for the Indian races and does for the first time extend real equality. The men will be paid the same pay as our own trainees from the Ministry of Labour, and their wives in India will be paid allowances by the Ministry, according to the arrangement we are making. This is forging a new industrial link between the East and the West.”[14]

The first batch of 50, chosen from over 200 applicants, so-called Bevin Boys sailed from Bombay in February 1941. They were chosen carefully from each province that was allocated a certain quota. The scheme was to keep them in training for about six months, while living with the local working-class families. Dr Ambedkar’s associate P. S. Bakhale, from Bombay Textile Labour Union, was the head of the Tribunal overseeing the sending of the Bevin Boys[15]. Starting in 1942, Dr Ambedkar, as Labour Minister, answered several Parliamentary queries regarding the status of employment of the Bevin Boys[16]. In April 1945, in an address to the chairman of the Tribunal at Shimla, Dr Ambedkar appreciated the help that Bevin Scheme would provide for the future of India, but urged them that “if the country’s industrial expansion is to assume proportions which are being generally visualised there is need not only for the skilled workers but for qualified higher grade technicians and for men capable of undertaking the direction and management of industry.”[17] In total about 900 or so young Indian men received training in the UK under the scheme. In my search through the archives, to piece this information together, I also came across a letter of appreciation written by Dr Ambedkar in February 1946 to the then Secretary of State for India Mr Amery (see below).

I sincerely hope such petitions and letters would be included in the future volumes of BAWS. In the end, all that can be said is that Dr Ambedkar’s tireless efforts and principled actions, such as this one hitherto unknown, should not be forgotten. The future biographies, if they are to break new ground, must include this chapter in his life, however little information we may have of it today.

Endnotes:

[1] The event that forms the subject of this article dates in the same eventful month that Dr Ambedkar was listed in the 1915’s NY State Census (1 June 1915) and also earned his Master’s the next day (reported in New York Times, 3 June 1915).

[2] The interesting Constituent Assembly debate regarding Trade and Commerce may be read on the Indian Kanoon here.

[3] Various articles from Times of India (“Cottage Industries & Cooperation,” 14 January 1924 with Social Services league at DT Hall, Bombay; “The Present Problem of Indian Currency,” 28 February 1925 with Servants of India Society Hall, Girgaum, Bombay; “Public Meeting on Economic Matters: Report of the Royal Commission on Indian Currency and Finance,” at the Indian Institute of the Political and Social Science, Girgaum, Bombay 19 August 1926, to name a few).

[4] Bureau of Commercial Economics: Industrial Information By Means Of The Cinematograph, 1914 accessible here on Archive.org

[5] Dr Ambedkar owned a few typewriters – some of which are now preserved in Shantivan Chicholi in Nagpur – that were manufactured by Remington Typewriters, which is featured on this list as being a contributor.

[6] Columbia University Alumni Register, 1754-1931, Compiled by The Committee on General Catalogue accessible here on HathiTrust, and relied on for piecing this article together.

[7] Various newspapers from those times, too long a list to cite, but some can be seen on Google News Archive or on Library of Congress too.

[8] “Ambedkar’s hitherto unseen intercontinental-travel and census records, some of which expose baseless claims”, Forward Press

[9] Report on Public Instruction in the Baroda State For the Year, 1916-1917 (1919), GIPE (PDF version), Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics’s DSPACE accessible here.

[10] This only came to fruition, as per the papers, because of a contractor from Cincinnati by the name of J. M. Gist who met Sayajirao Maharaja of Baroda in a “conference” to arrange this comparative study, during his travel to India.

[11] Earlier only known as School of Mines of Columbia College, but then split into various schools, such as Engineering, Chemical, etc. He probably had a degree from NYU, too.

[12] I, for one, would not miss the importance of the order of signatories listed, to suggest that Dr Ambedkar, despite not being the seniormost among the other signatories, was closely associated with the petition, perhaps even spearheading it himself.

[13] “Pictures Without Money and Without Price”, The Sutton Register (Sutton, Nebraska), 31 May 1923, p 3

[14] Times of India, dated 25 November 1940

[15] “...Thirdly, the Union acknowledges with gratitude the valuable legal advice given to it on several legal points that arose out of the complaints received by the Union, by Dr B. R. Ambedkar, Messrs. S. C. Joshi, P. S. Bakhale and H. A. Talcherkar,” Historical Origin of the Salt Tax, (PDF version accessible here), Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics’s DSPACE.

[16] BAWS Vol 10, summarily listed here

[17] Times of India, 21 April 1945

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in