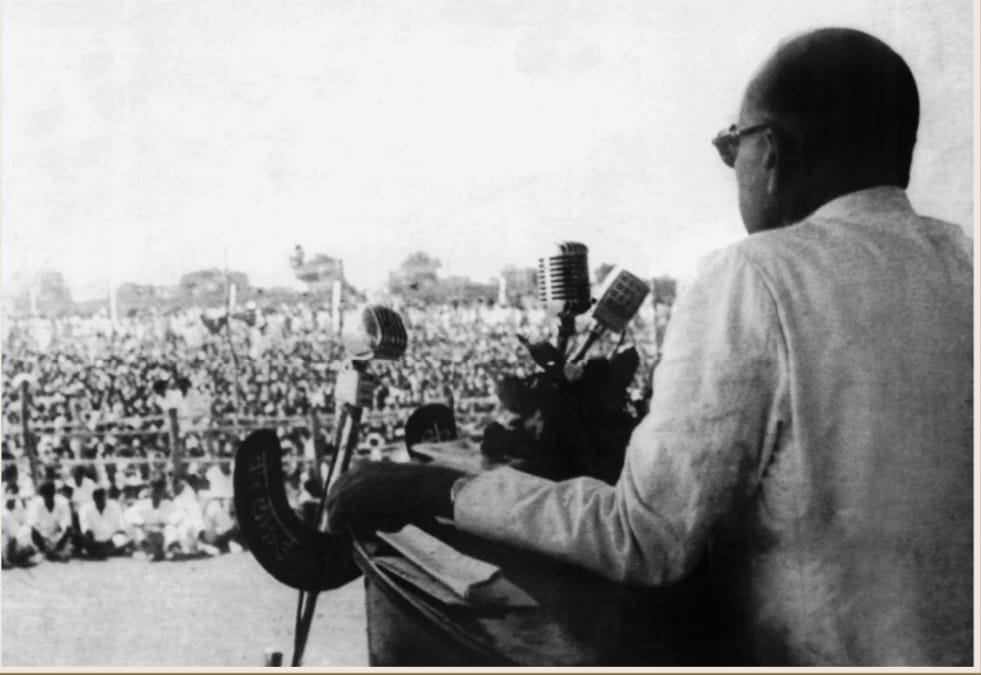

Dr B.R. Ambedkar passed away at 65 years of age on 6 December 1956. In his lifetime, he had interacted with a multitude of people from different walks of life. As an undisputed champion of the masses, we are very well aware of his untiring efforts to reach out to members of different communities across the subcontinent. That was one of the reasons for his enormous contributions for the emancipation of the suffering humanity.

In the capacity of a political leader, he had interacted with national and international leaders from all hues of the political spectrum, like King George V, Winston Churchill, Harold Laski, W.E.B. Du Bois, Éamon de Valera and Gandhi, not to speak of his meetings with religious leaders ranging from Swami Shraddhanand of Arya Samaj to the Pope of Rome (1930s) and so on. His meeting with the Pope was so iconic that Time magazine reported that Dr Ambedkar is “probably the only man alive who ever walked out in a huff from a private audience with the Pope of Rome” when the latter replied that “it may take three or four centuries to remedy these abuses” to which Untouchables were subjected[1].

While some of us might have heard about these interactions of Dr Ambedkar with political and religious leaders, few of us would know about Dr Ambedkar’s association with personalities belonging to domains other than politics and religion. In an earlier article[2], I covered the interactions that Babasaheb had with personalities belonging to the world of films, theatre, and music, and in this article, I shall aim to document his meetings and interactions with leading scientists of his time.

In my limited research, I found documented evidence of at least four leading Indian scientists who had interactions with Dr B.R. Ambedkar. They were Dr Meghnad Saha, Sir C.V. Raman, G.D. Naidu and Homi Bhabha. This article aims to cover these interactions in fair detail. Let us begin with Prof Saha:

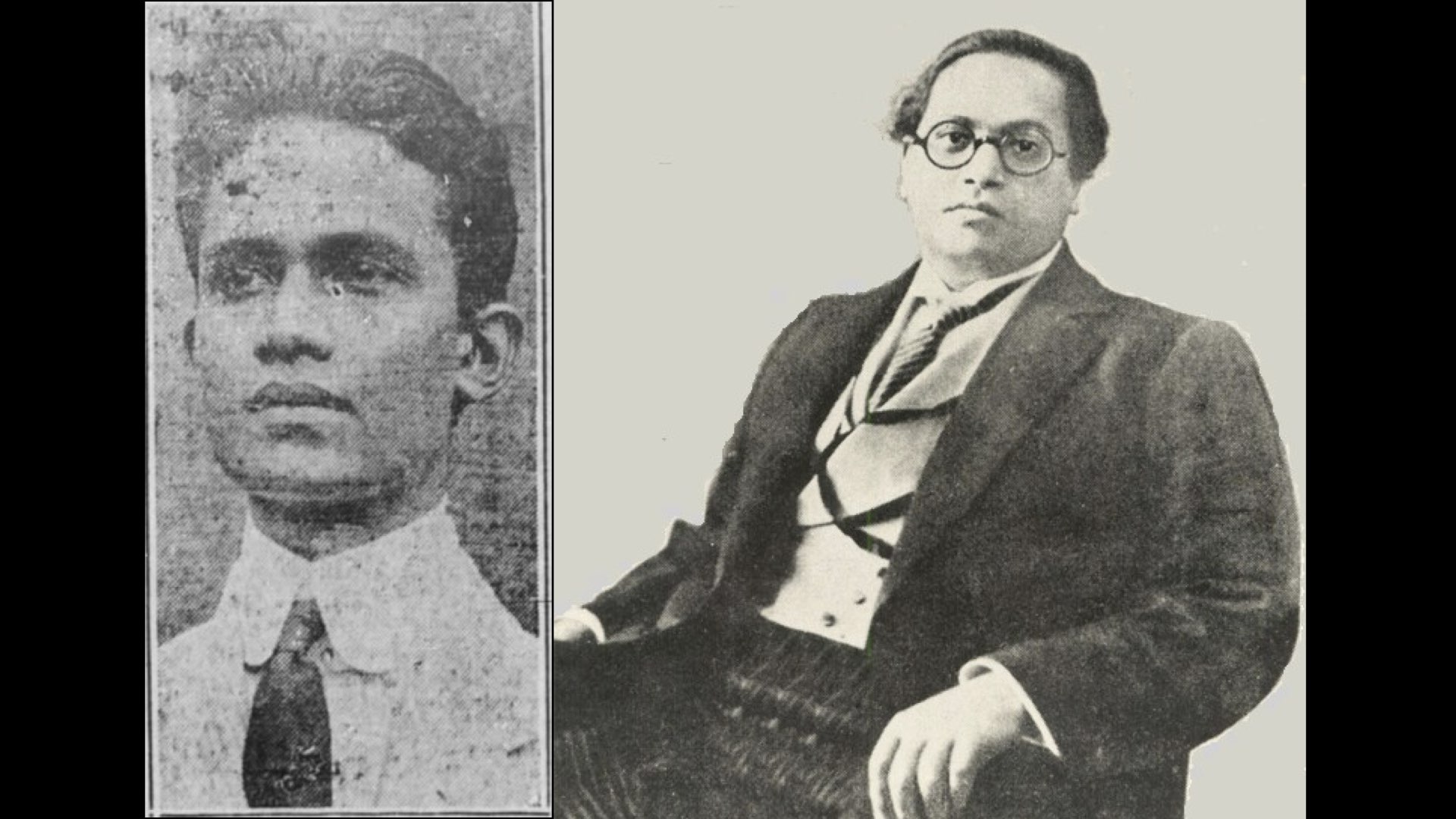

Dr Meghnad Saha and Dr Ambedkar

Legendary astrophysicist Dr Meghnad Saha was born on 6 October 1893, in a small village (Sheoratali) near Dacca (Dhaka today) into a lower-caste family[3] (some say he belonged to the formerly untouchable Namashudra community). Owing to poverty, he could not afford to go to a good school. But his sheer determination enabled him to receive many scholarships to pursue higher education. He went on to earn an MSc in Mixed Mathematics from Presidency College and a DSc from Calcutta University in 1919 for his thesis “On the Origin of Line in Stellar Spectra”.

Dr Saha is widely recognized for his pathbreaking ionization equation, which is used and will continue to be used in astrophysics for countless generations to come. Saha’s equation allowed astronomers to determine the chemical composition and temperature of stars by analyzing their spectra (light). Before this, stellar spectra were a mere mysterious pattern. Saha was only 27 when he propounded this equation!

Commenting on the legacy of Saha’s ionization equation, the great physicist Sir Arthur Eddington wrote, “Prof. Saha’s Theory of Thermal Ionization is one of the twelve fundamental landmarks in astrophysics since the discovery of the first variable star (Mira Ceti) by Fabricius in 1596.”[4] It is interesting to note that Prof Saha was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing this equation (in fact, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize seven times in his lifetime).

To name a few more contributions of Prof Saha, he is also known for establishing India’s first cyclotron (a type of particle accelerator that uses a combination of electric and magnetic fields to boost charged particles to high energies along a spiral path) that fostered experimental nuclear physics; for reforming the calendar system in India by proposing that “The Saka era should be used in the unified national calendar” (Sakas were patrons of Buddhism); and for establishing many institutions like Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Institute of Nuclear Physics in Calcutta in 1949 (later renamed the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics (SINP) which became a cradle for nuclear and particle physics research in India).

One of the first documented interactions between Dr Meghnad Saha and Dr Ambedkar took place in 1943-44 when Babasaheb was the Labour Minister in the Viceroy’s Executive Council [1942-1945]. As noted by S.B. Karmohapatro, Prof Saha met Dr Ambedkar on multiple occasions during this period to discuss the idea of a Damodar River Valley Project[5].

In order to truly appreciate the significance of this meeting, we need to set it against the backdrop of floods in the region of Bengal. From 1871, Bengal had witnessed many major and minor floods, of which the floods that occurred in 1871, 1922 and 1943 were particularly devastating. Dr Saha, who had been a witness to the catastrophic impact of floods from his childhood, has always desired to regulate the flow of mighty rivers. His views on this issue have been summed up by Pramod V. Naik:

The flatness of the country and comparative shortness of the rivers was such that normal floods had to be discharged by a large number of channels or branches. It resulted in delta-building activities on a large scale causing widespread topographical changes, within comparatively short intervals of time, creating serious problems in agriculture, sanitation and distribution in population. That could be easily seen from the position of the present and the distant past.

… Before 1787, the river system of Bengal was such that floodwater was equally distributed over the whole province, and the problems of malaria and erosion were not on a large scale.

… Saha suggested that both temporary and permanent remedies lay in restoring the river system, as much as possible to the state which it had before 1787. For that, engineering operations needed were almost on an unparalleled scale.[6]

In 1943, Bengal saw a disastrous flood that cut Calcutta off from the rest of the country for three months. This was also the period of World War II, when the eastern region of India was threatened by the Japanese army. It is in this crucial context that Dr Saha stepped in to throw light on the problem of flood. He wrote a series of articles in magazines to explain the gravity of the situation. Responding to the call of Prof Saha, the Bengal government appointed a Damodar Flood Enquiry Committee. The Maharaja of Burdwan was chairman, and Prof Saha was one of the members of this committee along with N.K. Bose.

Prof Saha suggested that the Damodar river system could be deployed for a multipurpose scheme to not only regulate the flow of the river but also to extract electricity and so on. But, unfortunately, the uncertainties of war halted the entire process. It is at this crucial juncture that Dr Saha met Babasaheb Ambedkar to suggest solutions to resolve the imminent crisis. Dr Ambedkar responded positively to the suggestions made by Dr Saha and initiated the grand plan of reconstruction in no time.

Writing in the journal Science and Culture, Dr Saha appreciated the efforts and initiatives of Labour Ministry in this regard and remarked: “The Labour Department of the Government of India is to be congratulated in undertaking seriously such a project, which is the first of its kind in India.”[7]

As a Labour Minister in Viceroy’s Executive Council, Dr Ambedkar made pioneering and path breaking contributions in diverse departments – Irrigation, Waterways and Drainage Inland Water Transport, Electric Power, River Valley Authorities, Multi-Purpose and Regional Development of River Valley Basins, Technical Expert Bodies and so on. He also drafted the crucial National Level Reconstruction Plan, Post War Economic Plan, and so on to provide a solid framework for the large-scale industrialization in India.[8]

Speaking about the river valley projects initiated under the leadership of Dr Ambedkar, a report prepared by Central Water Commission of Government of India notes:

The river valley projects which were under the active consideration of the Labour Department during 1944-46 were the Damodar River Valley projects, the Sone River Valley projects, the projects on Orissa rivers, including the Mahanadi, and the Kosi [in Bihar] and others on rivers Chambal and rivers of the Deccan. These projects were conceived essentially for multipurpose development with flood control, irrigation, navigation, domestic water supply, hydro power and other purposes. The Labour Department was also required to assist the States in their small storage or retardation dams in the States of Baroda, Jaipur, Kathiawar, Cutch, Nawanagar, Bundi, Aundh, and Morvi for conservation and control of flood water.

… Ambedkar was instrumental in ushering in the coordinated development of the Damodar basin by the Central Government. As a member in the pre-independence Cabinet he pursued vigorously the development proposal for Damodar Valley. He directed that its development should be on the lines of Tennessee Valley Authority and supervised a great deal of the preliminary work. With this kind of ground work, the Damodar Valley scheme became the first river valley development scheme in postindependence India, with the Damodar Valley Corporation getting established by the act of Parliament.[9]

It will be impossible to even summarize all of Dr Ambedkar’s contributions as Labour Minister [1942-45] in this article because they are so numerous. Therefore, I had confined myself only to his initiative of river valley projects, and his association with Dr Saha.

In designing policies on water, river valley projects, and so on [just like for other departments], Dr Ambedkar did an intense study of the whole discipline and numerous past legislations to provide fresh and illuminating insights. In this process, he differed with the preeminent engineer Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya on some crucial questions. Dr Ambedkar gave this scintillating exposition that remains valid even today:

Given the resources, why has Orissa continued to be so poor, so backward and so wretched a province? The only answer I can give is that Orissa has not found the best method of utilising her water wealth. Much effort has undoubtedly been spent in inquiring into the question of floods.

… From that year [1928] down to 1945, there have been a series of committees appointed to tackle this problem. “The Orissa Flood Enquiry Committee of 1928 was presided over by the well-known Chief Engineer of Bengal, Mr Adams Williams. In 1937, the enquiry was entrusted in the able hands of Sri M. Visvesvarayya, who submitted two reports – one in 1937 and another in 1939 …

… With all respect to the members of these committees, I am sorry to say they did not bring the right approach to bear on the problem. They were influenced by the idea that water in excessive quantity was an evil, that when water comes in excessive quantity, what needs to be done is to let it run into the sea in an orderly flow. Both these views are now regarded as grave misconceptions, as positively dangerous from the point of view of the good of the people.

It is wrong to think water in excessive quantity is an evil. Water can never be so excessive as to be an evil. Man suffers more from lack of water than from excess of it. The trouble is that nature is not only niggardly in the amount of water it gives, it is also erratic in its distribution – alternating between drought and storm. But this cannot alter the fact that water is wealth. Water being the wealth of the people and its distribution being uncertain, the correct approach is not to complain against nature but to conserve water.[10]

As Law Minister (1947-1951) and the chief architect of India’s Constitution, Dr Ambedkar made many significant changes to the Government of India Act 1935 with respect to the Union’s role in regulating rivers and river projects. As noted by the Central Water Commission,

When the draft Constitution was submitted on February 21, 1948 it was obvious that it had benefitted from the influence of Ambedkar, who was Chairman of its Drafting Committee, especially as regards independent India’s water policy. The draft Constitution included articles 239-242 corresponding closely to Sections 130-134 of the Government of India Act, 1935, as adapted in 1947. These articles used the earlier phrase ‘water from any natural source of supply’. List 1 of the Seventh Schedule (viz. Union List) to the draft Constitution, however, made a major departure from the 1935 Act and placed the development of ‘inter-State waterways’ under the Union List, the relevant item being: ‘74. The development of inter-State waterways for purposes of flood control, irrigation, navigation and hydro-electric power’.

… On September 9, 1949, Ambedkar moved another amendment to insert draft article 242 A as follows, in place of draft articles 239-242: Adjudication of disputes relating to waters of inter-State rivers or river valleys and 242 A (1) Parliament may by law provide for the adjudication of any dispute or complaint with respect to the use, distribution or control of the water of, or in any inter-State river or river valley …’

… This draft article came to be adopted as Article 262. In accordance with this provision, Parliament enacted the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956 and the River Boards Act, 1956. The former provides, in the words of its preamble, ‘for the adjudication of disputes relating to the waters of inter-State rivers and river valleys’. The River Boards Act, in turn, provides ‘for the establishment of River Boards for the regulation and development of inter-State rivers and river valleys,’ in terms of Entry 56.[11]

Shocking as it is, far from acknowledging these gigantic contributions of Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the then Congress government made many deliberate attempts, right from the beginning, to erase Babasaheb from the pages of this glorious history.

In this context, it was Dr Meghnad Saha who, speaking in the Lok Sabha, proudly reminded the political leaders and the thinking public of the time about the pre-eminent role of his dear friend Dr Ambedkar in the various river valley projects and other development projects for the progress of our nation.

Attacking the Congress government in the Lok Sabha over their insatiable enthusiasm to take credit for projects in which they had zero role, Prof Saha said:

May I say, as one who had been connected with the Government of India in the pre-Independence days as a member in several committees, that this Government do not deserve any credit for any of the constructive works that had been started. As regards the Sindri Fertiliser Factory, I might claim that I was responsible for bringing that point of view before the country in 1943… There was a great famine in Bengal then, and I sponsored an article in the ‘Science and Culture’ about it, and I was told that I would be put in jail. 1 had said, why this dearth of food, it is because we have no fertilisers in this country and Lord Linlithgow, the Viceroy, was against the use of artificial fertilisers.

… This article came before the Viceroy’s cabinet, and Sir Ramaswamy Mudaliar took it up, and appointed a committee consisting of Sir James Pitkeathly and two Indians. They made all the plans, but when the plans were ready, these came before the Congress Government. But there was an apprehension that the whole plan was going to be wrecked, because a very great Congressman said, ‘we have got plenty of cow-dung in this country, and therefore, no artificial fertilisers are necessary’.

… Anyhow, the cow-dung theory did not find favour because the late lamented Dr Shyama Prasad Mookerjee was there. He said, the plan is there, some work has been done on it, I must see that it is worked up to a finish. That is the whole story of the Sindri Fertiliser Plant, for which the present Congress Government is taking credit …

The same thing holds good about the Damodar Valley Project, about the Bhakra Nangal Project and other projects for which the Congress Government are taking all the credit. The credit for all these river valley projects – if it is to be given to anybody – should be given to Dr Ambedkar.

An Honourable Member: Or to the Britishers.

Shri Meghnad Saha: He [Dr Ambedkar] was a member of the Viceroy’s Council. He saw the whole thing through and laid the foundation for it. All that this Government have done is to mismanage the affairs.

Shri Algu Rai Shastri: Was he then in Government or not?

Shri Meghnad Saha: Yes, at that time.

Shri Shankar Shantaram More: Not of yours.

Shri Meghnad Saha: He [Dr Ambedkar] was the Minister of Fuel and Power in the Viceroy’s Cabinet … I wish to explode the myth that the Congress has been responsible for anything constructive which has been done in this country, except to waste money on community projects and on many other themes. If you have to industrialise this country, you must give your brain a racking, which you have not done so far.

On another occasion in Lok Sabha, Prof Saha reiterated:

In place of the 2500 crores of rupees set apart by the Bombay Planners for industrialisation, we have provided a meagre sum of Rs 306 crores. This sum includes the sum which will be spent on industries proper and also half of power and irrigation. Of these 94 crores are to be obtained from the public sector. Therefore, we find that industrialisation has been completely ignored. Of course, the government have … the Sindri Fertiliser Factory which is not due to this Government but due to the initiative of Ramaswamy Mudaliar.

…We also have the River Valley Projects in our hands, the multi-purpose projects – which have, as I have a mind to say, led to multipurpose corruption [due to the Congress government]. This [River Valley Projects] is also due to the initiative of my friend Dr Ambedkar.[12]

Like Dr Ambedkar, Prof Saha too could not escape the wrath of casteism in his life. For instance, when he was staying in Calcutta University’s Eden Hostel, the so-called upper caste students refused to have dinner with him! As noted by Pramod Naik, “Some of his childhood memories were unpleasant. At a function of Saraswati puja, one priest rudely asked him to get down from the dais, because he was not from the upper caste (as per the foolish notions of Indian caste system) … One can imagine the impact of this incident on a little proud boy! From that day onwards, Meghnad stopped taking part in rituals of worship.”[13]

Prof Anirban Pathak remarked, “Saha himself was a victim of the Indian caste system, and he was naturally against it. He could never accept it and asked fundamental questions, like: ‘Why will the social respect of an uneducated priest who recites chants in Sanskrit without knowing their meaning be more than that of a cobbler or a weaver?’”[14]

Dr Saha’s attacks on the caste system can be found in a Bengali magazine called Bharatbarsha. For example, Dr Saha asserted that one of the disastrous effects of the evil caste system is the complete disconnect between the brain and the hand, and that its consequences have proved to be detrimental for the progress of our nation. The following is the translation of Saha’s words by Prof. Anirban Pathak:

I have looked into the issue from a different perspective. In my opinion, the caste system has completely destroyed the link between our brain and hand, and that’s what put us much behind Europe and USA in the development of the materialistic modern civilization. From the middle-age, Indian intellectuals were busy in discussing their bookish knowledge and surprising others by the depth of their abstract knowledge. They were hardly connected to real life. They never thought of doing something for the development of industry and business. Probably, doing so would have had them thrown them out of their community (caste)

… Similarly, the warriors were busy in showcasing their power using the available weapons; they never tried to learn or adopt new technologies and techniques evolved in other countries. India has not invented any useful technique or procedure for a long time as, here, only the works done with the brain have been given a high position compared to the works done with hands. That’s what has cut the connection between the brain and hand.

… Today, an American student or a professor is not reluctant to do the work of a carpenter or another technician, but an Indian student is. Unless our intellectuals themselves work with the machines, and technicians come in close contact with intellectuals, new machines and technologies will not be developed, as happened in Europe and America.[15]

It is very interesting to note that there are many striking parallels in the thinking process of Dr Ambedkar and Prof Saha ranging from their critiques of theology and superstitions to their emphasis on the potential of science and technology in tackling poverty and hunger, the nationalization of insurance, the revival of the salt tax, and, most importantly, their incisive attack on Gandhi, his mad love for villages and the iniquitous varna-caste system. There is so much to write on it, and I shall deal with these parallels in detail in my upcoming article on Dr Saha and Dr Ambedkar.

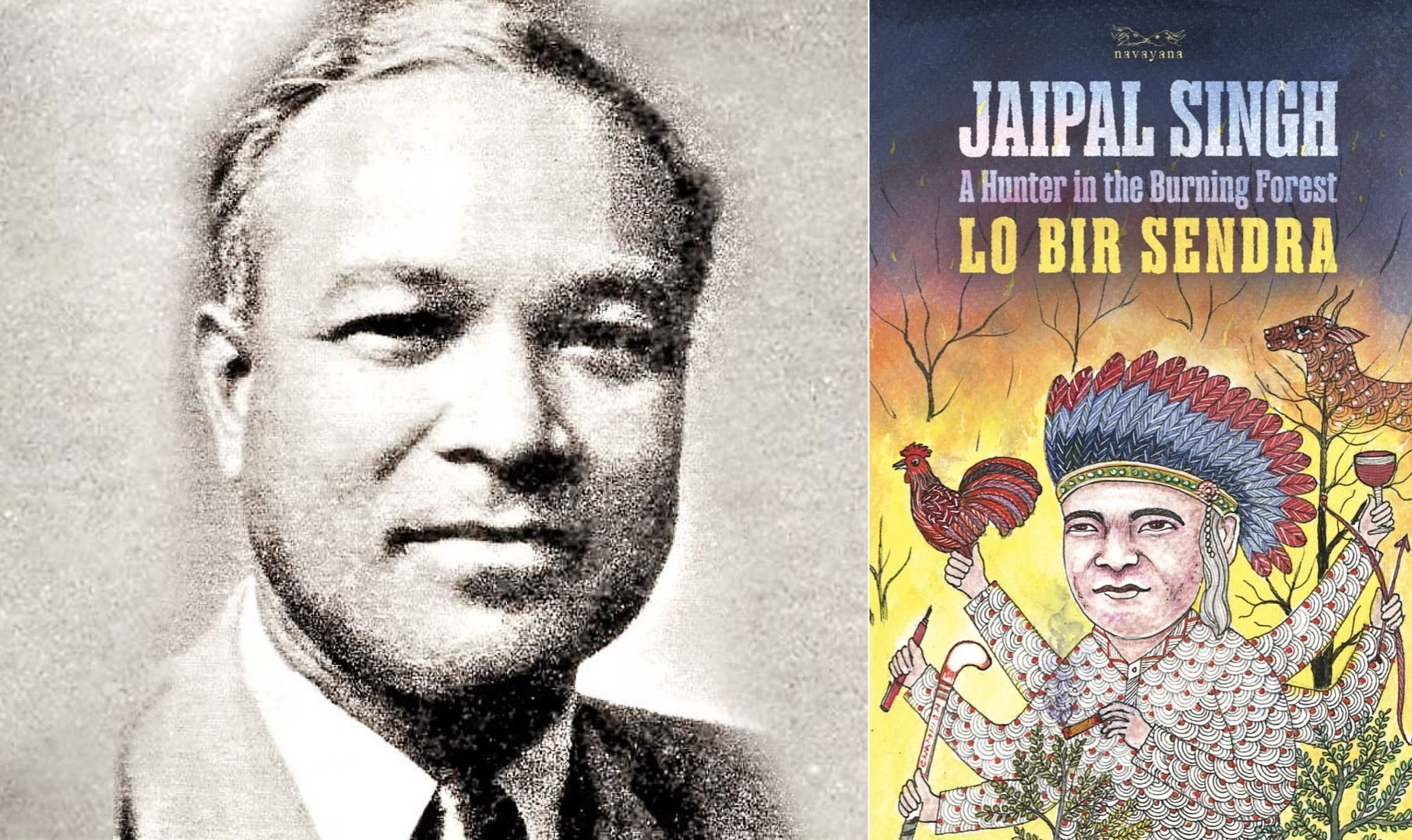

G.D. Naidu and Dr Ambedkar

Gopalswamy Doraiswamy Naidu was born on 23 March 1893 in a village called Kalangal, which is around 26 km from Coimbatore (then Madras Province and today Tamil Nadu). G.D. Naidu’s story is as interesting as remarkable because he made terrific contributions in science and technology although he did not have any formal training or education in science.

Speaking about the contributions of G.D. Naidu, R. Akileish writes:

He [G.D. Naidu] worked in the agricultural fields in the mornings and read Tamil books in the evenings to become a self-taught man. At the age of 20, he saw a motorbike in his village for the first time driven by a British official and was fascinated by “how it could move without any external power such as horses or bullocks”… Thereafter, Naidu did odd jobs in Coimbatore, including that of a waiter at a restaurant and saved about Rs 400 in three years to purchase a two-wheeler, which he dismantled and reassembled by himself to understand its mechanism.

While visiting Belgium, he experimented with fixing a motor from a toy car to a shaving razor, which led to the birth of ‘Rasant’ electric razor. Having patented it in Europe, he manufactured the razors on a larger scale by importing motors from Germany, casings from Switzerland and steel from Sweden. ‘Rasant’ razors sold around 7,500 pieces in the first month of its introduction in London and American magazines even carried advertisements for Naidu’s device in the 1940s.

Other devices which were a product of his innovations were vote recording machines, orange juice extractors, coin-operated phonographs, electronic calculators, lathes with German collaboration and 16-mm projectors. Naidu also experimented with constructing low-cost houses for the urban poor that could be built in a day.[16]

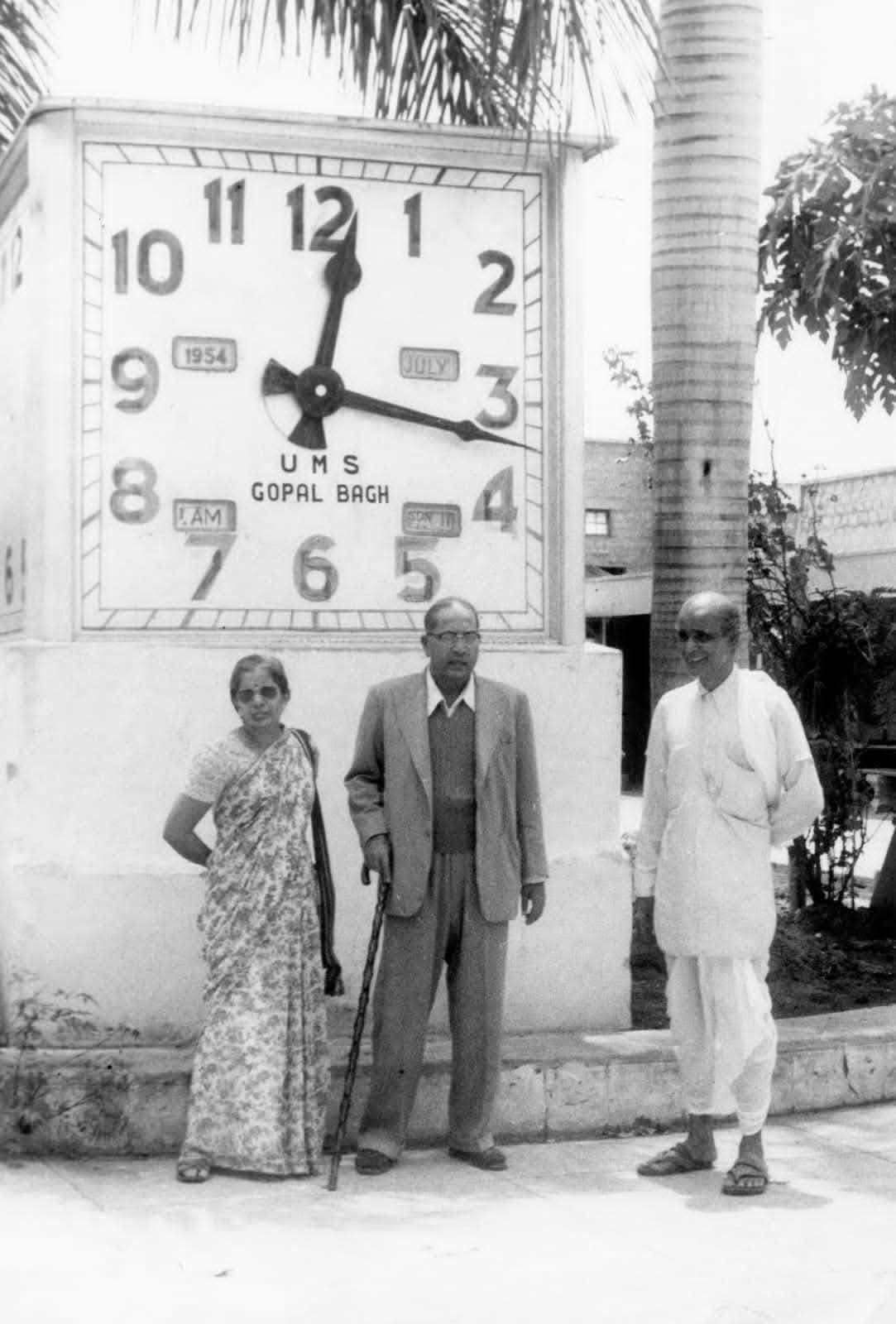

We don’t know when G. D. Naidu met Babasaheb for the first time, but based on the images that are available in social media, one can safely guess that they had been great friends since the 1930s. It is highly probable that their involvement in the Non-Brahmin or Dravidian movement is what drew them together. Speaking about the impact of the Non-Brahmin movement on G.D. Naidu, Professor G.M. Natarajan says: “The first simple marriage of the city [Coimbatore] was that of L.G. Balakrishnan (G.D. Naidu’s first son-in-law) in 1944. It was attended by leaders like Periyar and only tea was served. G.D. Naidu himself had a Dravidian wedding without any priests.”[17]

Sir C.V. Raman, Homi Bhabha and Dr Ambedkar

Dr Ambedkar founded Siddharth College in Bombay in 1946 to provide higher education to the marginalized sections. His focus was science and technology. The following words of Babasaheb explain his inclination:

Education in Arts and Law cannot be of much value to the Scheduled Castes either to the graduates themselves or to the people. It has not been of very high value even to Hindus. What will help the Scheduled Castes is education of an advanced type in Science and Technology.

… But it is obvious that education in Science and Technology is beyond the means of the Scheduled Castes and this is why so many of them send their children to take up courses in Arts and Law. Without Government assistance, the field of Advanced Education in Science and Technology will never become open to the Scheduled Castes, and it is only just and proper that the Central Government should come forward to aid them in this connection.[18]

Dr Ambedkar introduced science and technology courses in his college and invited many leading thinkers of his era to share their wisdom with students and inspire them to pursue academic research in Science and Technology. Among the invitees were Sir C.V. Raman and Homi Bhabha.[19]

Homi Bhabha visited Siddharth College in 1946 and gave lectures to students on the significance of science in the modern world. It has been reported that Dr Ambedkar called Homi Bhabha the new hero of India.

Nobel Laureate Sir C.V. Raman visited Siddharth College on 3 February 1949. Speaking about his experience at Siddharth College, Raman noted: “It gave me much satisfaction to have been in a position to visit the Siddharth College and go round the class rooms and the laboratories. It is evidently a most flourishing institution and one can hope that in the years to come, it will attain a position such as its founders evidently had in mind, when they prompted it. I earnestly hope that in the national desire to enlarge the field of educational effort, the urge towards reaching the highest standards and especially the development of research activities will not be lost sight of. It pleased me to see that the desire of the teachers to take part in the scientific research has already found expression in at least one department.”[20]

It would not be out of place here to state that Dr Ambedkar had intended to start a Buddhist seminary (an institution to train students as Buddhist bhikkus and scholars) in Bangalore, near the Raman Institute founded by C.V. Raman. For this purpose, he met Maharaja Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar (the king of Mysore) in 1954 as a part of his South India Tour. Excited by the proposal of Dr Ambedkar, Maharaja Jayachamarajendra granted him a 5-acre plot – situated between the Raman Institute and the Indian Institute of Science.[21]

It is remarkable to note that Maharaja Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar’s uncle was none other than Maharaja Krishna Raja Wadiyar IV, who introduced reservations in government jobs for Backward Classes, Women, and Untouchables way back in 1919 as per the recommendations of civil servant Sir Leslie Creery Miller (Shahu Maharaj introduced reservations for marginalized sections in Kolhapur in 1902). In this process, Maharaja Wadiyar faced severe opposition against reservations for marginalized sections from no less a person than Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya [the then Dewan of Mysore], who ultimately resigned from his post in 1918 after a series of tussles with the Maharaja.[22]

To conclude, from the above discussion, it is clear that Dr Ambedkar interacted with at least four leading scientists of his era. The number could be higher, and an in-depth research of Babasaheb’s Marathi writings and speeches and his unpublished works in English would throw light on many more such amazing interactions.

References

[1] ‘Religion: Untouchable Lincoln’, Time magazine https://time.com/archive/6755156/religion-untouchable-lincoln/

[2] Sairam, S.P.V.A (2025). ‘An Unexplored Side of Dr Ambedkar: His Quiet Relationship with Cinema, Theatre, and Music’. The Culture Cafe https://www.theculturecafe.in/p/an-unexplored-side-of-dr-ambedkar

[3] Ramesh, Sandhya (2023). “Meghnad Saha—polymath, politician, pioneer scientist who is called ‘Darwin of astronomy’”. The Print https://theprint.in/theprint-profile/meghnad-saha-polymath-politician-pioneer-scientist-who-is-called-darwin-of-astronomy/1792478/;

Swaminathan, Padmini (2011). “Are ‘scientific’ institutions gender-prejudiced?”. The Hindu https://www.thehindu.com/books/are-scientific-institutions-genderprejudiced/article2548119.ece; ‘Science to history: the Raman Effect’. Nature https://www.nature.com/articles/nindia.2012.151

[4] Naik, Pramod V. (2017). ‘Meghnad Saha: His Life in Science and Politics’. Springer

[5] Karmohapatro, S.B. (1997). ‘Meghnad Saha’, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. Accessed here: https://archive.org/details/meghnadsaha00sbka

[6] Naik, Pramod V. (2017). ‘Meghnad Saha: His Life in Science and Politics’, Springer

[7] Sen, S.N. (1954). ‘Professor Meghnad Saha: His life, Work and Philosophy’. Meghnad Saha 60th Birthday Committee, Calcutta

[8] Thorat, Sukhadeo (2006). ‘Ambedkar’s Role in Economic Planning, Water and Power Policy’. Shipra Publications

[9] ‘Ambedkar’s Contribution to Water Resources Development: A Research Project by Central Water Commission’. It can be accessed here: https://cwc.gov.in/sites/default/files/ambedkars-book_1.pdf

[10] Ambedkar, B.R. ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches’, Volume 10 https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_10/pdf/321

[11] https://cwc.gov.in/sites/default/files/ambedkars-book_1.pdf

[12] Chatterjee, Santimay and Gupta, Jyotirmoy (Eds) (1993). ‘Meghnad Saha in Parliament’. The Asiatic Society, Calcutta. Accessed here (pages 74 and 119): https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.181906/page/n141/mode/2up?q=ambedkar

[13] Naik, Pramod V. (2017), ‘Meghnad Saha: His Life in Science and Politics’, Springer

[14] Ghatak, Ajoy and Pathak, Anirban (Eds) (2019). ‘Meghnad Saha: A Great Scientist and Visionary (Lectures delivered at the 125th Birth Anniversary Celebration of Professor Meghnad Saha)’. A Publication of The National Academy of Sciences India (NASI). Viva Books, Delhi

[15] Ibid

[16] Akileish, R. (2022). ‘G.D. Naidu: An innovator for all seasons’. The Hindu

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/gd-naidu-an-innovator-for-all-seasons/article65186422.ece

[17] Jeshi, K. (2013). ‘The fact finder’. The Hindu https://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/history-and-culture/the-fact-finder/article4534039.ece

[18] Ambedkar, B.R. ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches’. Vol 10 https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_10/pdf/448

[19] Facebook page of Siddharth College of Arts, Science and Commerce Alumni Association, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/17YaoUhtwW/

[20] Ibid

[21] Ambedkar, B.R. ‘Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches’. Vol 10 https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_17_01/pdf/453

[22] Ramnath, Aparajith (2024). ‘Engineering a Nation: The Life and Career of M. Visvesvaraya’. Penguin Viking. Chapter 13, ‘A Dewan at Work’

Updated on 20 December 2025, 12.54 pm.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in