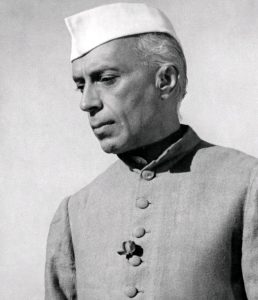

The first Lok Sabha was formed on 17 April 1952. With its first sitting held on 13 May the same year began the evolution of the language of parliamentary democracy in India. The opposition said that the Congress represented merely 45 (44.99) per cent voters. Jawaharlal Nehru hit back saying that the biggest opposition party (Socialist Party) represented only 10.5 per cent voters and the second biggest (Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party) only 5.8 per cent whereas the Congress represented at least thrice the number of voters of both the parties taken together. Thus, a new language of interaction between the ruling and the opposition parties came into being. But was this language authentic and honest? Did the ruling and the opposition contingents really represent as many voters as they claimed to?

Developing its own language is a sine qua non for the establishment and sustenance of any system. For instance, Brahamanism has its own language and has been dominating our society for thousands of years. We cannot go into its details here, but we can only develop the capacity to identify it. What is indisputable is that the language developed by a system is used both by its supporters as well as its opponents. The speciality of this language is that it suppresses dissent. The proponents and opponents of Brahmanism speak in the same language just as the opposition and the ruling groups do in a parliamentary democracy.

For instance, in the first general election, the Congress was not supported by 45 per cent of the voters; it was backed by only 23 per cent of the voters. In that election, of the 17,32,13,635 eligible voters only 8,86,12,171 exercised their franchise. Of those who cast their votes, 44.99 per cent backed the Congress. But they formed only 23 per cent of the total eligible voters.

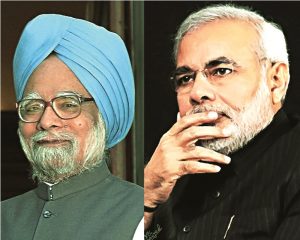

This language has remained unchanged since the first general election. The outcome of the election to the 16th Lok Sabha was presented as if Narendra Modi’s party enjoyed an overwhelming support of the people. The fact is that it got only 31 per cent of the votes and statistics are clear that among the parties that have formed governments on their own, the BJP’s vote percentage is the lowest. Until now, no party has formed a government at the Centre with only 31 per cent of the votes. But when one talks in the language of ‘winning a majority’, these critical facts are obfuscated.

The language of parliamentary democracy conceals many such vital facts. The government rules over all the citizens of the nation. It is claimed that it has been voted to power by a majority of the people but the reality is quite different. To begin with, only a part of the population makes up the voters. Until the minimum age for voting was brought down from 21 to 18, the percentage of voters in the population was even lower. Broadly, we can say that of every 100 Indians, 70 are voters. Of them, a maximum 60 per cent, ie 42, exercise their franchise. Till date, the highest percentage of votes received by the ruling party was in 1977 when the Janata Party received 52.74 per cent of the votes cast.

Against this backdrop, one can only imagine what getting 31 per cent of the votes cast means when juxtaposed against the total population of the country. While governments in parliamentary democracies draw their legitimacy from the support of the ‘majority’, the truth is that they are backed by a very small minority of the nation’s population. If economic inequities are increasing in society, shouldn’t the rule of minority governments share some of the blame? What is the reason that in a parliamentary democracy, no one discusses how the support of a minority of the population is projected and presented as winning a majority?

This is just an example. This basic character of the language of parliamentary democracy works at other levels as well. When Manmohan Singh was the prime minister, on many occasions he said that Naxalism/Maoism was the biggest threat facing the nation. He used to quote figures provided by the Union Home Ministry to substantiate his claim. He claimed that more than 75 per cent of the (then) 28 states in the country were in the grip of Naxalism; but the number of Naxal-affected districts was pegged at 118. This is only about 25 per cent of the districts in the country. Now, if the same figures are projected at the village level, we will discover that only 2 per cent of the 6 lakh-plus villages of the country are affected by Naxalism. Thus, you may say 75 per cent of the states, 25 per cent of districts or only 2 per cent of the villages are affected by Naxalism. And all your statements would be true and factually correct! It is clear that a change in language changes the entire perspective. If you calculate things in a different manner, you arrive at a different conclusion.

Although these two examples are not enough, they do underline the need to follow, understand and analyse the language of the present power structure based on the ground realities of a parliamentary democracy and socio-economic inequities. It is the media that helps establish the language of parliamentary democracy, Brahmanism or any other system based on inequalities. The media keeps on parroting this language day in, day out so that no new language can take its place. Those who live in this unequal society should learn to decipher this language, they should be able to see its duplicity. They will have to develop their own language. For instance, they should never forget that the party which rules from Delhi enjoys the backing of only a very small section of the populace. Those in power are unwilling to share it with anyone. If the political, social and cultural contradictions in our nation and society are growing, it is partly because we lack a majority government in the real sense of the term.

Published in the August 2014 issue of the Forward Press magazine

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literaturehttps://www.amazon.in/dp/B073JVMCTHThe Common Man Speaks Out

https://www.amazon.in/dp/B075R94LQJ

Mahishasur: A people’s hero

https://www.amazon.in/dp/B072JV4X77

Published in the August 2014 issue of the Forward Press magazine