There is more than a poignant irony in the Prime Minister’s call for a “Congress-free India.” This call to rid India of the party that supposedly liberated us from British colonialism is being issued close to the 125th anniversary of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

The call for a Congress-free India is a call for one-party rule, which in practice means, one-man rule. PM Modi seems to consider multi-party democracy to be an aspect of Nehru’s failed legacy. He seems to think that India has to imitate China’s “successful” political model of one-party rule.

Nehru’s failed legacy

This past Diwali. The RSS Chief was rightly indignant that the market was flooded with Hindu gods and goddesses, “Made in China.” Chinese firecrackers were one-third the price compared to Indian patakhas.

Earlier, in August, I was told that the best and the cheapest rakhis came from China. Chinese do not celebrate Rakshabandhan; they make rakhis exclusively for Indians. It was this shameful reality that gave a sharp edge to Prime Minister Modi’s Independence Day slogan “Make in India.”

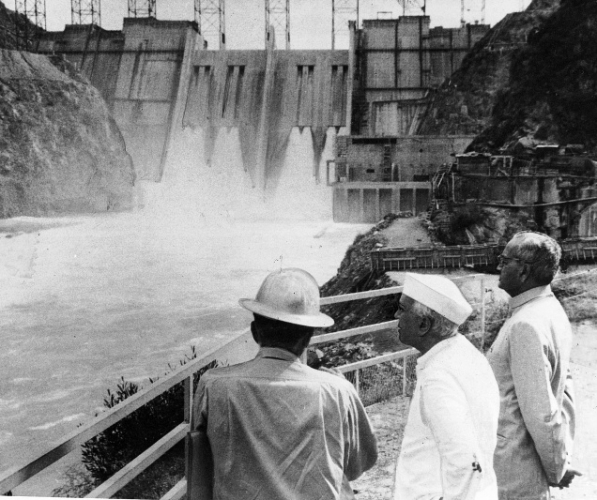

The irony is that originally, “Make in India” was Nehru’s call. He issued it eight decades prior to Modi. And Nehru was dead serious. By 1938 he had succeeded in coaxing a reluctant Congress to create the National Planning Committee. They punished Nehru with its Chairmanship.

Nehru had not actually to head something as time-consuming as a committee. Yet, the challenge to transform India into a productive nation grew upon him. It sucked-in his whole being. Nehru became the architect of the vision to make India an industrial nation.

During its 1939 session in Karachi, the Congress debated and adopted Nehru’s vision. It went on to commission Nehru’s Planning Committee to develop the details of the plan’s broad outlines. Nehru made that task one of his top priorities.

But the Second World War broke out. In October 1940, Nehru was arrested before he could receive and incorporate the reports of all the sub-committees into a national plan. He urged the sub-committees to function without him. But the entire political community was in disarray. Undaunted, Nehru tried to turn his cell in Naini Central Jail into the de facto headquarters of the National Planning Committee. The jail authorities ruled that out.

Post 1947, as the Prime Minister, Nehru didn’t forget Naini. He turned the Planning Committee into the national Planning Commission and took a keen interest in transforming Naini into an industrial centre on the outskirts of his home-town, Allahabad, and parliamentary constituency, Phulpur.

Over the last six decades, serious attempts were made to start at least two dozen major and umpteen small scale industries in the Naini – Allahabad area. Sixty percent of the major industries and ninety percent of the small scale industries have already failed, while others are struggling.

Free India’s industrial failure in Nehru’s hometown is sobering. Naini is across the confluence of Yamuna and Ganga. The two perennial rivers connect us with the most populous parts of India. We have a railway junction that connects us to the whole country. We have some of the oldest educational institutions in the country – including plenty of institutions offering technical education. Allahabad has one of the most vibrant political communities. It has given five of the first seven Prime Ministers to the nation. It is the home to UP’s High Court, military cantonment, and an outstanding Air Force base. Needless to say, Prayag (Allahabad-Naini) is also one of the premier religious centres of Hindu India. So, why did Nehru’s efforts fail to make his home town one of North India’s industrial hubs?

Since the failure of Nehru’s legacy is clear, the nation did not protest Modi’s decision to dismantle a symbol of Nehru’s legacy – the Planning Commission.

Can Modi learn from Nehru’s failures

Contrary to Mahatma Gandhi’s idealized village India, Nehru and Modi are both correct that India needs to become an industrially productive nation. Nehru laid the foundations upon which we have to build. The problem is that as yet there is no indication that Narendra Modi even understands why Nehru’s attempt failed so miserably that we have to import idols of Hindu gods and goddesses from atheistic China.

Though Nehru was a great man, he failed in his grand vision for an industrialised India because he failed to understand and address three issues: caste, culture, and character.

Marx’s intellectual impact made it impossible for Nehru to even study the caste problem. He naïvely assumed that his socialism would soon make caste irrelevant. In his Presidential Address to the Indian National Congress session in Lucknow, Nehru said on 12 April 1929, “Under socialism there can be no … differentiation or victimization. Economically speaking, the Harijans have constituted the landless proletariat, and an economic solution removes the social barriers that custom and tradition have raised . . .”

Marx’s assumption that economics determines everything made Nehru so blind that he, could not see that one or two upper castes had captured the Congress. For other reasons, neither could Indira, nor Rajiv and they all certainly chose not to do anything about it.. Such caste-corruption was what drove other castes out of the Congress to create alternative platforms for themselves.

Against the resulting fragmentation, Modi is trying to promote the very culture that Nehru rightly considered the cause of India’s backwardness. While he was in jail in August 1934, Nehru wrote this in an article: “. . . what are we? A passive, inactive, and indolent race forgetful of the idea of freedom or honour. Our guiding principles in life are a number of restrictions. Thou shalt not eat or drink with another, thou shalt not touch such and such, thou shalt not cross the seas and so on and so forth. The one great restriction of old we have forgotten: ‘Thou shalt not be subjected to slavery’. … The world has marched on and left us far behind immersed in our superstitions and observances which we do not even understand. Like our old architecture, our faith has lost its ancient purity and simplicity and has been covered up with a mass of abuses and crude symbols and orientations. Today the keepers of our consciences are men, narrow and bigoted and with no knowledge of anything except empty forms and ceremonials . . . There is no room for bigots in the modern world. We must cultivate the spirit of enquiry and welcome all knowledge whether the source of it is the East or the West.”

Why Modi’s “Make in India” campaign will fail

Modi’s assumption is naïve that iron-fisted “good governance” will ensure that we and the world will “Make in India.” Governance is a practical problem but the deeper issues are cultural. Modi’s well-meaning scheme will fail if he ignores things like culture, caste and character. A practical issue is that while one man’s iron rule can bring bureaucratic babus to their desks on time, it will necessarily slow down real decision-making and governance. Another is obvious: dismantling the Planning Commission does not equal creating a better alternative. Be that as it may, Nehru’s legacy failed because although he wanted Indians to make things; he did not know how to make the right kinds of Indians.

Nehru inherited one of the world’s cleanest bureaucracies and an idealistic political party. Yet, he did not know what had created that “steel frame” of good governance. In contrast, Modi has inherited a corrupted structure of governance. Therefore, before he can govern he has to fight against his own governing machinery. Modi thinks that his iron fist can clean his machine’s rust and crookedness. But he already knows that in order to govern well, he has to be ruthless against his own team. The likelihood is that this in-house fight will leave a lot of wounded egos and little time and energy to govern. The fight could force him to destroy Nehru’s greatest legacy – political freedom. And the BJP is likely to become the Badshah’s first victim.

Modi, like Nehru, wants to “Make in India.” Yet, just like Nehru, Modi has no clue on how to make Indians with character: How to make them productive, without depriving them of democratic freedom.

Nehru was a great man. He earned the right to become free India’s first prime minister, because, in order to create a British-free India, Nehru went to jail 10 times for a total of nine-and-a-half years. Whoever would aspire to build on Nehru’s legacy must successfully address and overcome the three “made in India” problems that Nehru downplayed and Modi cannot solve: caste, culture, and character.

Published in the November 2014 issue of the Forward Press magazine

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)