Since the last Lok Sabha elections, the BJP has consistently done well in almost all the state elections. Statistics show that the party is getting the support of a substantial number of Dalitbahujan voters, who, until recently, had maintained a safe distance from the party. It would be an exaggeration to attribute this trend only to the Modi magic or wave. It is more a function of the BJP’s well-crafted strategy, reflected in the alliances the party has forged with Dalit-OBC leaders.

Is this alliance only aimed at winning elections or is there is a long-term agenda to it? Why, one may ask, do the Dalit leaders not seem to be anywhere near their declared objective, the logic, of their association with the BJP – ie, coming to power. Kanshiram’s “Power is the ‘gurkilli’ [master key]” is a popular maxim of Dalit politics. Why do the sociologists seem to be in a hurry to announce the return of the “age of chamchas [flatterers]’’? Is the politics of Dalit leaders destined to play second fiddle to the dominant castes for ever? Is this the lull before the storm, even as the BJP’s too-clever-by-half strategists employ and re-employ the formula invented by them?

Before dwelling on these questions, let us quickly survey some incidents from the past and the present to make sense of what is happening, and analyze the situation.

Politics of images

- In Jabbar Patel’s film Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, there is a scene where the Hindu Mahasabha leader Dr Moonje comes to Ambedkar and tries to convince him that even if he wants to switch religions, he should choose a religion of Indian temperament and background, such as, according to him, Sikhism. Moonje promises Ambedkar that, as a quid pro quo, the Hindu Mahasabha will support his demand for reservations for Dalits. In response, laughing derisively, Ambedkar says, “You old wily Brahmin, you intruder!” (Note: This is a dramatization of a true incident.)

- At the Round Table Conference, Mahatma Gandhi, describing himself and the Congress as the greatest well-wisher and leader of the Dalits, says that he does not support Ambedkar’s demand for a separate electorate.

- In Bihar, during the run-up to the 2014 Lok Sabha polls, the BJP was celebrating the birth anniversaries of Dalit icons that Dwijs disdain, such as Baba Chuhadmal, whom the people of the Dusadh caste (Ramvilas Paswan’s vote bank) idolize and the Bhumihar-Dwijs (BJP’s caste base) hate.

- Immediately after Mayawati described the BJP government as casteist, the BJP announced that it would celebrate the birth anniversary of Savitribai Phule and it kept its promise. This was the first time that the BJP celebrated the birth anniversary of Savitribai. Mayawati’s “casteist” remark was for the government conferring the Bharat Ratna on Atal Behari Vajpayee and Madan Mohan Malaviya while ignoring Kanshiram and Mahatma Jotiba Phule.

- Eyeing Bihar Chief Minister Jeetan Ram Manjhi’s vote bank (Mushar and Bhuiyan castes), the BJP is making an all-out effort to draw Manjhi into its camp.

- The BJP has taken the initiative to purchase the house in London where Dr Ambedkar stayed while studying at the London School of Economics. Though the efforts in this direction had begun under the UPA government, the BJP government is giving them concrete shape.

When Dalit leaders changed their loyalties

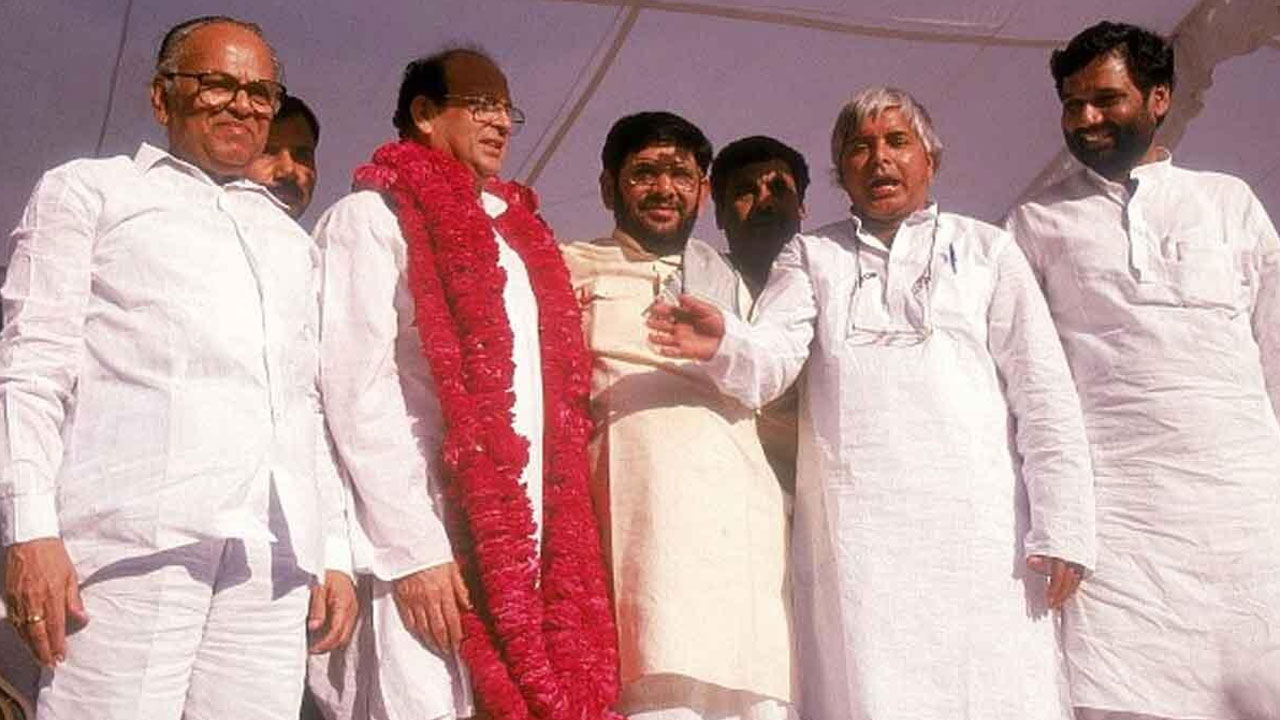

Against this backdrop, the images of Dalit leaders – Ramvilas Paswan, Udit Raj and Ramdas Athavale – sharing the stage with the then BJP prime ministerial candidate and now the prime minister, Narendra Modi, are still fresh in public memory. These leaders were known for their declared/implied secular image and for their contrarian views vis-à-vis Hinduism.

Udit Raj was quite vocal in opposing aggressive Hindutva and had declared from time to time that he intended to get a large number of Dalits converted to Buddhism.

When the Vajpayee was prime minister, Ramvilas Paswan had disassociated himself from the NDA-I citing administrative failure of the then Modi state government during the riots in Gujarat and, in the process, had emerged as a champion of secularism. His politics has been centred on balancing Dalit-Muslim-Dwij equations. Paswan broke off from the NDA when, under the leadership of Laloo and Nitish Kumar, OBCs had risen to power in Bihar and had begun dominating state politics. Paswan’s detractors point out that he took this decision when the Vajpayee government had only one and a half years of its term left.

Ramdas Athavale is counted among the secular Dalit (Buddhist) leaders. He has been raising his voice against communalism of all hues. He effectively played the role of a politician who protected the Muslims and the immigrants of Mumbai whenever Hindutvavadis or regional chauvinists tried to torment them. It was widely believed that Athavale’s politics was a big roadblock for the communalists.

The association of these Dalit leaders, as well OBC leaders such as Upendra Kushwaha and Anupriya Patel – known for their vocal advocacy of social justice – with the NDA or directly with the BJP, led to the party’s smashing electoral victory last May. Besides the votes they brought, the BJP also gained psychologically with these leaders joining its ranks. But this factor was lost sight of in the din of the Modi wave.

Though Upendra Kushwaha has been made a minister of state in an important ministry – Human Resources Development – he has little to do. Recently, Smriti Irani, who is the Cabinet minister for HRD, issued a circular with the directive that the answers to the questions asked in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha pertaining to her ministry would not be sent with the signatures of ministers of state. A competent leader like Kushwaha has no option but to work under and be at the mercy of someone who was in the news for her disputed degrees. Regardless, he will have to repay this “debt” by ensuring that his supporters back the BJP in the Bihar Assembly polls this year.

Anupriya Patel’s case is a bit different. The BJP may argue that she lacks experience and so cannot aspire for a ministerial berth. But then, an equally inexperienced Irani has been given an important assignment. There is no doubt about Anupriya’s leadership qualities. She has proved them time and again.

In the last Lok Sabha polls, Laloo Yadav’s confidante Ramkripal Yadav rode the Modi chariot. That not only fetched him headlines in the newspapers but gave immense psychological benefit to the BJP too. Ramkripal Yadav is a veteran politician and has been a member of both the Rajya Sabha and the Lok Sabha for many years. However, in the Modi government he has had to be satisfied with being the lowly minister of state for drinking water and sanitation – that too belatedly. It was part of a well-planned strategy of the BJP to have these leaders compromise on their declared objectives and bring them on board. But these leaders have no place in the long-term politics of the party. Ultimately, the BJP’s aim is to win over Dalibahujan voters directly, without the mediation of these Dalitbahujan leaders.

Pushed to the margins in nine months

The BJP government could not keep these Dalit leaders in its womb even for nine months. They have been left to their fate, their anxiety is palpable and clashes appear imminent. On 8 December, a public meeting was organized by the BJP’s Dalit face Udit Raj at Delhi’s Ramlila Maidan under the aegis of All India Confederation of SC/ST Organizations. Among BJP’s top leaders, Nitin Gadkari was present at the event, but despite the official announcement that he had agreed to attend, the party chief Amit Shah did not turn up. And it was his absence that was more talked about than Gadkari’s presence. Earlier, on 3 December, at a rally organized under the banner of Akhil Bharatiya Dalit Mahasabha, Amit Shah and Delhi BJP leader Satish Upadhyay were present but Udit Raj was conspicuous by his absence. It is said that Udit Raj had not been invited to the rally. Though Udit Raj has given various explanations for these absences, they are indicative of the brewing tension, especially against the backdrop of his demand for a ministerial berth.

Meanwhile, to keep the myth of Modi magic alive, the BJP has brought Kiran Bedi into its fold. The idea is to share the spoils of the Anna agitation with AAP. It has also managed to draw Congress’ influential Dalit leader Krishna Tirath into its camp. Apparently, it is not ready to take any risk vis-à-vis Dalit votes. Krishna Tirath’s entry may sound warning bells for Udit Raj, for the BJP now has two pawns on the political chessboard of Delhi to woo Dalit voters.

RPI’s leader Ramdas Athavale is still worse off. The political circles were agog with rumours of his induction into the council of ministers twice but they remained what they were: rumours. Athavale had justified his support to the BJP with the argument that it would help achieve the goal of getting 15 per cent share in power. But neither was he made a minister at the Centre nor did his party get a share in power in the new BJP-led state government. He has not expressed his dismay and anger openly but he does not fail to tell anybody who cares to listen that during the Maharashtra Assembly elections, he was promised in writing that he would be made a Cabinet minister at the Centre.

The political pundits say that the fall in the RPI’s vote share from 0.8 per cent in 2009 to 0.2 per cent in 2014 was due to the fact that while the RPI ensured that its supporters voted for the BJP candidates, the BJP could not persuade its voters to back RPI candidates. RPI leader Sidhnath Dhende says that in the Pimpri reserved constituency, the party’s candidate got just 3,000 votes less than the victorious Shiv Sena candidate. The NCP candidate was the runner-up, having lost by around 2,000 votes. It is clear from this outcome that the RPI did not get the BJP votes. In Vidarbha, despite its influence, Ramdas Athavale’s party was not allowed to contest a single seat, but it helped the BJP score a scintillating victory.

What happened with Sanjay Paswan, the national chief of BJP SC/ST Morcha, was no less appalling. He is being cold-shouldered by the leadership of the party. His fault: He did not want to contest from a constituency reserved for the SCs. Dismissing the talk of his disillusionment with the BJP leadership, Sanjay Paswan, who was minister of state for Human Resources Development in the Vajpayee government, says, “I will definitely contest whenever the party finds a general constituency suitable for me.”

Although Paswan has not been very vocal in expressing his disenchantment with the BJP, he has sent a clear message to them by organizing a function for the release of a book Bahujan Rajneeti kee nayee ummed: Jeetan Ram Manjhi (The new hope of Bahujan politics: Jeetan Ram Manjhi). The book sings paeans to JDU leader and Bihar Chief Minister Manjhi. He says: “I am very much in the NDA and I am doing whatever I can to protect the interests of the Dalits. My demand is that my government should strengthen MGNREGA and promulgate a law to stop the misuse of the funds meant for the welfare of the SCs/STs. Bringing out a book on Manjhi does not at all indicate that I am preparing to desert the party. Why don’t you take this is as an attempt to bring Manjhi ji, who is being neglected by the leaders of his party, into the BJP?”

Even veteran and influential Dalit leader Ramvilas Paswan is finding that his political clout is waning. He has been made in charge of a comparatively unimportant ministry and despite his best efforts, he has failed to secure even a junior cabinet berth for his son Chirag Paswan.

Round two of BJP strategy

The Dalit leaders have been caught between the devil and the deep sea. They can neither quit the BJP/NDA nor try new political experiments, at least for the time being, even as the BJP works very hard to gain a foothold among their traditional supporters. The associate organizations of the RSS are pitting the Dalit castes against the minorities to lend stability to the Modi government, which, according to them, is the first Hindu government of the country after hundreds of years. At the same time, the party is trying to form emotional ties with the Dalits by showing reverence for Dalitbahujan symbols and icons. But this does not mean that the party has abandoned its efforts to bring Dalit leaders into its camp. It is constantly sending feelers to Manjhi.

As some incidents quoted at the beginning of this article show, the BJP, like the Congress of Gandhi, is trying to establish itself as the real representative of the Dalits and the Backwards. Like Gandhi, Modi has already declared himself the leader of the Dalit-Backward communities by flaunting his backward and chaiwallah credentials. On the other hand, the Dalit leaders lack the courage and wisdom of an Ambedkar, who, while accepting the challenge of Gandhi’s mass following and Moonje’s deceit, continued to unite the Dalits. He gave them the guarantee of a secure future and built their leadership. These leaders do not even have the courage to express their concern over the growing communal violence in which Dalits are being used as fodder.

They are not to blame

Social and political thinker Premkumar Mani, who was a JDU member of the Bihar Legislative Council, says that while it is true that the mass entry of the Dalit leaders into the BJP was unexpected, it is also true that they hardly had any other option. The Congress was taking them for granted and the Backward leadership of the Socialist parties was kicking them around like football while the leftist leadership and the intellectual class lived in ivory towers and suffered from casteist prejudices. Mani recalls that when the Vajpayee government fell, the communist intellectuals of Patna remarked that with religious fascism having met its end, it was time to take on casteist fascism. They forgot that the forces they referred to as casteist fascists were, in fact, those which had fought for social justice and challenged the communal forces. He says, ‘‘Dalit leaders had no options left. But I am not interested in whether they are getting any ministry or not. I am interested in whether they are making any united and meaningful effort to advance the interests of the Dalitbahujans.”

The road ahead

The BJP’s strategy is clear. It wants to appropriate the Dalitbahujan vote bank. And it appears to be giving preference to Dalit leaders – to some extent, even at the cost of its Dwij workers. It seems this strategy is going to be used in the 2017 Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections. But the party’s top Dwij leadership is confident that all this will not translate into any decline in its importance or influence in the party. It finds reassuring the dominance of the Dwijs in the Council of Ministers and in the Central Secretariat. By snubbing independent and Ambedkarite Dalit leaders from time to time, the party is making it apparent that it has co-opted the policies of both Moonje and Gandhi. This is the Sangh-BJP model of Dalit politics. One has to see if and when the simmering anger among the Dalit leaders over their being sidelined bursts into the open and what shape it takes. While it would be premature to assume that the era of flattery is back, it will not be easy for the Dalitbahujan leadership to prove these analyses or speculations incorrect. They will have to change the ABCs of their politics. The BJP had adopted their politics of cultural identity. The Dalitbahujan leaders will have to come up with concrete economic and social issues.

Published in the February 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine