Since Independence, India has been a democracy with the Constitutional mandate to build an inclusive-egalitarian society. But India also has a millennia-old culture of caste and its consequences. Evidence suggests that the most stubborn gene of India’s social DNA is the hierarchical ethos of caste and Brahmanism. It is in this sense that Ambedkar in a 1948 speech to the Constituent Assembly had described democracy in India as “only a top dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic”.

Caste is a system of graded inequality and graded exploitation (not just a system of inequality and exploitation). It embodies a built-in mechanism to push people towards a status-ridden, hierarchic downgrading and this process results in a systematic dehumanization of people at the lower rungs. Many castes among a single class (occupying a similar position within the division of labour) fragment and divide that class, making any unity impossible. With scriptural sanctions and social indoctrination, graded hierarchy guarantees the perpetuation of the hierarchical system and prevents the rise of united social discontent against the discrimination of caste and class. Thus, the most glaring contradiction of Dalitbahujans is the same thing that they share: caste-class discrimination is also the thing that divides them.

Crisis of Dalitbahujan leadership

A cursory glance is enough to see that gender and caste discrimination is rampant in the subjugated castes. Internalization of caste values and patriarchal norms is especially strong among the OBCs. A few powerful groups among them oppress the Dalits and behave no different than the upper castes. These communities and their traditional leaders also fail to engage with internal oppressive power relationships, especially in regard to women. The so-called leaders who cannot take the lead in addressing the fundamental aspects of social life are, in fact, a big part of the problem. The need for serious self-scrutiny and self-criticism among these communities cannot be overstressed. The suffering people will have to produce leaders with the ability and integrity to address the basic issues that keep them down. The new leaders should be thinking people who are intellectually equipped and cognitively prepared to assess the social problems in a way that promotes egalitarian change.

The notions of high and low and the need to fit into one’s assigned role in the graded hierarchy are strongly entrenched in the people’s psyche. Any change thus requires the everyday politics to evolve into a sustained struggle for cultural transformation. There is a crying need to engage with rampant contradictions among the subjugated castes, especially between Dalits and the OBCs.

A beginning can be made with recognizing the problems, and honest internal criticism and self-scrutiny. To begin with, those who believe in social justice have to recognize and get rid of their own casteist prejudices and mindsets. This will prepare the ground for reconciliation and unity, for a joint struggle. Thus, the OBCs should reach out to the Dalits and the more-exploited castes and communities. But the current OBC politicians, obsessed as they are with crude power politics, neither have an understanding of the complexity and contradictions of caste nor do they want to engage with oppressive power relationships whose worst victims are Dalits and women. Most OBC politicians are intellectually and morally challenged, and they don’t have the basic intellect and decency to reach out to the more oppressed communities.

On the whole, OBC politicians have shown little imaginative commitment to egalitarianism and democracy in the sense of making society just and sharing power with Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and other vulnerable communities. The Dalit and Adivasi politicians fare better but only marginally. The pitfalls of blind identity politics, competitive indulgence in corruption, and bitter fragmentations along caste and sub-caste lines among the Dalitbahujan parties are now out in the open. The SP and BSP’s bitter parting of ways, imprisonment of many top Dalit-OBC leaders for corruption, and the shameless silence, to give but one example, of the entire Dalitbahujan leadership over the acquittal of all the accused of the Laxmanpur-Bathe massacre make this abundantly clear.

The problem thus is much deeper than it appears. The caste elite accuses, not wrongly, the Dalit-OBC politicians of perpetuating caste-based politics. But this is only a half-truth, as the caste politics that the Dalit-OBC leaders indulge in is just a shield for their politics of amoral familism – treating the family as the only realm of trust and empowerment, and thus concentrating and centralizing all power in the family. Most OBC-Dalit leaders do not trust their own caste people, let alone the larger communities of OBCs or Dalits; they do not trust anyone beyond a tight family circle. Their personalized power politics, ideological bankruptcy and a complete lack of empathy for the suffering Dalitbahujans now stand thoroughly exposed. It is these people who have given national politics on a platter, in a manner of speaking, to the BJP and the Congress, which represent two sides of the brahmanical politics at the highest level. This is clear from the fact that most Dalit-OBC politicians are now with these two parties; the rest are leading their one-man-one-family parties. Nothing can be more damaging for the larger Dalitbahujan interest than their perfidious politics. These money-and power-hungry buffoons have reduced Dalitbahujan politics to a shameless family business.

The upshot of all this is that Dalitbahujans are still nowhere in the contest of ideas, policies and visions – the fundamentals on which democratic competition takes place. There is no cultural-political framework in sight within which Dalitbahujans can come together. The project of critiquing and dismantling Brahmanism and caste – started by Phule, Ambedkar and Periyar – has practically been given up for petty personal or sectional interests. There is no serious engagement with the new matrix and mechanism of dominance in the wake of massive material and technological changes brought in by modernization, urbanization and marketization. There is no attempt to create a new political vision that can challenge the seductive myths of meritocracy, equal opportunity and upward mobility.

The talk revolving around providing basic amenities like bijali-sadak-pani – hyped in the media as an antidote to the regressive caste politics – entirely ignores the issues of larger policy or perspective. Similarly, in this age of rampaging privatization, an obsession with some ragtag welfarism, narrow quotaism and cultural tokenism amount to nothing less than courting disaster. The fact is that such crumbs and tokenism help maintain the awfully unrepresentative character of the judiciary, the bureaucracy, the army, the media and the academia. They also help maintain an attitude of resignation to the ongoing privatization of natural resources and commercialization of education, which are reinforcing a new caste-class system whose worst victims are none other than the Dalitbahujans.

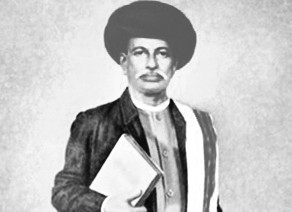

Imperative of a renewed Phule-Ambedkarite discourse

The problem is not just that the Dalitbahujans are far away from the Indian development story but also that they do not have an effective vision that can lead to a united action for desirable change. Of course, they have a longstanding aspiration for emancipation, and there have been ideas and movements in history from the days of the Buddha to our own to cast away the chains of subjugation (which have resulted in some social mobility and changes), but the subjugation – multiple and cumulative, hidden or reflected in contemporary surveys and statistics – remains. India is still one of the world’s most unequal societies, and the oppressed communities do not have a critical vision of emancipation. They do not have an ideology, a leadership and an organization, and thus they are unable to mount a movement for social change.

What are the fundamental factors that have kept the Dalitbahujans politically domesticated and intellectually paralyzed, not allowing an alternative vision (which can become the mainstream vision for India’s transformation) to emerge? The answer to this question will require us to interrogate the entire system. Above all, it will require us to grasp the multidimensional (secular as well as religious, and thus, all-pervasive) nature of the Indian status system anchored in the graded caste hierarchy and its nexus with other forms of inequalities such as class and patriarchy, which caused divisions within the oppressed castes and between these castes and other marginalized communities.

No one understood this more incisively than Phule and Ambedkar. Their insight into Indian reality was not based simply on written sources or epistemology, but also on practical reasons and lived experiences. Unlike the Western and Indian academics, they strove to understand the past through the present and vice versa. They critiqued the aggregate of religious constructs, the structure of hierarchy and political institutions that had been masterminded with the primary aim of keeping the masses ignorant, servile and disunited. In this process, they brought to light the brahmanical control and exercise of knowledge and the exclusion of lowered castes and women from the realm of education, all of which played a crucial role in moulding India in the caste culture and patriarchy. On the question of the nation, they hammered home the basic point that the nation is nothing if it is not the people. Unravelling the caste-class structure of society, they argued that a society divided by discrimination could not constitute a genuine nation. In the face of terrible odds, they fought against the forces that not only rationalized or masked the glaring inequalities of the past but actually sought to maintain them as the basis for their power in the present.

However, the cultural revolution that Phule and Ambedkar initiated, remained not only incomplete but was also ignored or distorted in the dominant discourse. Those who could have been India’s redeemers were mocked and marginalized as special-interest leaders of the “lower castes” and “untouchables”. In a famous essay, contemporary Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor has argued that “contemptible images” of a cultural community, consistently projected by a dominant group, can be legitimate ground for the politics of cultural assertion by the subordinate group. Refusal of equal recognition can inflict damage to those who are denied it; the projection of an inferior or damaging image on another can actually distort and oppress. What can be more dehumanizing and damaging than being labelled Shudra, untouchable and low-caste? The greatest of upper-caste Indian nationalists (such as Gandhi and Nehru, Tilak and Savarkar) refused even to recognize this, forcing the Dalitbahujan leaders to wage their autonomous struggles for freedom. In fact, the Phule-Ambedkar ideology had greater understanding of the social whole, as it represented the consciousness and aspirations of the oppressed majority, and was thus morally superior to that of Gandhi and Nehru, or Tilak and Savarkar.

At the core of the Phule-Ambedkar ideology was opposition to injustice in all its forms. Carrying forward this legacy means making India a social democracy. In today’s globalized India, two forces are fiercely competing for the heart and mind of India: liberal (capitalist) democracy and social democracy. This conflict is part of the larger global battle between the forces representing these forces. Liberal democracy, which is in the ascendancy today, is essentially a bourgeois-brahmanical democracy, revolving around self-regulated market and unrestricted rights to private property. Behind the façade of liberal democracy is the stubbornness of social conservatism. On the other hand, social democracy means not only civil and political rights but also some basic economic and social rights that cannot be ensured without prioritizing political responsibility over market forces. Committed to an exploitation-free society, social democracy implies popular participation on the basis of social inclusion, social security and an equal opportunity for everyone. In the Indian context, social democracy means a society free of the interconnected and multiple inequalities of caste, class and gender, which was the dream of Phule and Ambedkar.

If India is to transform from a caste society to a social democracy, there is a great need to resurrect the Phule-Ambedkar discourse. The biggest obstacles to this are the lack of critical mass education and the Dalitbahujans’ near-total absence from the process of production and dissemination of knowledge, notwithstanding the admirable work of some freedom-fighter intellectuals. Phule and Ambedkar had rightly traced the roots of cumulative elite dominance and cumulative mass demoralisation to the historical exclusion of the oppressed castes from the realm of education and its manifold consequences. The Dalitbahujans were not allowed to even imbibe the canonical, dominant knowledge, and their own organic knowledge evolved through experience went unrecognized and was even stigmatized, preventing the possibility of an alternate knowledge system emerging.

Without reference to history – the systemic cultural, intellectual and spiritual destruction of Dalitbahujans – one cannot find even poor answers to the complex problems that keep them fragmented and powerless. But the corruption, capitulation and ideological bankruptcy of the current Dalit-OBC leadership have also deepened the crisis. A cutting-edge understanding of the larger, dominant paradigm – the longstanding political and intellectual dominance of caste and its consequences – remains the challenge. And this must be complemented with the efforts to overcome the widespread internalization of casteist and patriarchal values. In the light of all this and the huge democratic deficit, despite all the changes taking place, the imperative of a renewed Phule-Ambedkarite discourse to democratize Indian society and emancipate the oppressed castes and communities cannot be overstressed. In that sense, the current crisis among the Dalitbahujans also presents an opportunity.

This article is extracted from the undelivered text of the Phule Memorial Oration, which was planned for 28 February 2014 at the Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, but had to be cancelled as the professor in charge of the event fell critically ill on the eve of the programme.

Published in the April 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine