“Jane wale lautkar nahin aate, jane walon ki yaad aati hai” (Those who have gone never return, only their memories keep coming back to us) – these popular lines of Diwakar Rahi, a “Shayar” from my own city, are playing in my mind as I try to come to terms with the passing away of Mudrarakshas. He will never come back but we will always remember him. Whenever I happen to visit Lucknow, his memories will come rushing back and I will acutely miss him.

Whenever I read Mudrarakshas, a powerful urge to meet him gripped me. But I didn’t know where he lived. At the time, I was not acquainted with any writer in Lucknow, except Darapuri, whom I used to meet occasionally at his Indira Bhawan office. As far as I remember, I was posted at Sultanpur then and kept visiting the Lucknow headquarters of my department on personal and official errands. The office was located at Kalyan Bhawan on Pragnarayan Marg. While travelling to Kalyan Bhawan from Charbagh, I would look out for a man with a French beard as I passed through GPO, Narhi, Sikandar Bagh and Gokhale Marg. That’s how I imagined him – a man with a French beard – from his photographs published in newspapers alongside his articles. Once a man sporting a French beard boarded a Vikram three-wheeler from Gokhale Marg and I intently peered at him, hoping that he would turn out to be Mudrarakshas. But that bulky man was not him. On another occasion, I looked for him frantically in the Ameenabad area. But lady luck never smiled on me and years later, when I visited his residence I discovered that he lived very close to Ameenabad. But that was not my first meeting with him. That was though the first time I visited his place.

I don’t remember the exact year of my first meeting with Mudrarakshas. It was probably 2000 or earlier. I saw and heard him for the first time at a Kathakram function. His lecture covered the Varna system, Vedas, Upanishads, Kautsa, Manu and Premchand, and was thought-provoking. I found that he was the only non-Dalit speaker who took Dalit discourse to a higher plane. At the dinner that followed the function, beer and whiskey were served. Barring a few, including Adam Gondwi and a couple of ladies, all were drinking. To tell you the truth, this was my first experience of such a gathering. Due to my inborn inferiority complex, I was feeling quite uneasy and out of place. I did not even know drinking etiquettes. A couple of times a year, I used to gulp a glass of country liquor in the company of drinkers. But here, there was a full-fledged bar. As I picked up a glass of whiskey and began adding beer (instead of water) to it, Shailendra immediately tapped me on my shoulder. “No, No! You don’t add beer to whiskey.” I was already feeling uncomfortable and this comment made me feel very awkward. After they had downed two-three pegs, Kashinath Singh, Rajendra Yadav and Shrilal Shukla began exchanging “non-veg dialogues”. I also saw Kashinath Singh drumming the bald head of Mudrarakshas, Shrilal Shukla making abortive attempts to embrace (the then) promising and now a well-established woman story-writer and Shashibhushan Dwivedi falling over a glamorous young woman author. All this was a new experience for me but Mudrarakshas was enduring these crudities smilingly. He kept on smiling even when his bald head was tapped. He had a weakness for liquor but he was not given to losing his head after he had a couple of drinks under his belt.

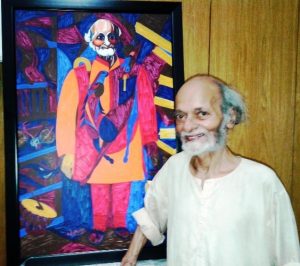

I could not have much of a conversation with him in that first meeting. But yes, I obtained his telephone number and address. I kept conversing with him over phone. I was a frequent visitor to Lucknow and whenever I had time, I visited the Rajendra Nagar-residence of Rajvaidya Mataparasad Sagar. He was one of the people who provided sanctuary to me in Lucknow when I fell on bad times. One day, I asked Vaidya the way to Durvijaganj, where Mudrarakshas lived. He said, “Turn left from Raniganj Square and head straight. You will reach his house.” I did reach Mudrarakshas’s home that day. In those days, mobiles were non-existent and there was no landline phone at Vaidya’s place; so I could not inform him in advance or take an appointment. I rang the bell. A young face peeped from a window and sought my introduction. I obliged and was ushered in. I was asked to wait in a small, sparsely furnished room. A picture hung on the wall of two children (a girl and a boy) kissing each other. There was a painting or two, some chairs and a table. And that was all. It was not a study in any sense as there were no books around. As I was surveying the surroundings, Mudrarakshas entered. “How are you Kanwal?” He asked.

“I am fine,” I replied.

“You are my favourite among Dalit writers.”

“That is your greatness.”

“I am told your name had been proposed for vice-chairmanship of Hindi Sansthan.”

He replied with distaste. “If I have to go, I will go to the Natak Akademi. Why I will go to that wretched place.”

Then we talked about Dalit politics. Beginning with the Poona Pact and Bhagat Singh, we reached the topic of today’s Communists. He accepted that Kanshi Ram was a Bahujan hero but bitterly criticized Mayawati. He was also extremely critical of Indian historians, especially Communist historians, for ignoring the freedom movement launched by Ambedkar and Phule for the emancipation of Bahujans. He said that this could mean only one thing – that all Communist writers had a brahmanical mindset. As I heard his thoughts with increasing fascination, I did not even notice that an hour had elapsed. My watch reminded me that it was time to push off and I sought his leave.

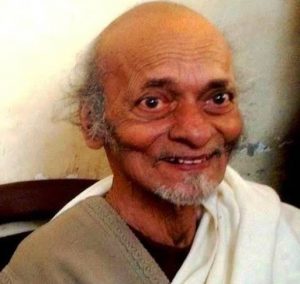

From then on, I met him on innumerable occasions, including in Kathakram functions. During the 2014 Kathakram function, he was ailing. He could not walk, even stand up, without help. But he still came to the function. What he said at the beginning of his speech was very touching. “As I was preparing to come here, my granddaughter told me, “You just dictate to me what you want to say. I will get it sent to the function venue. Someone will read it out.” But I said, ‘No, I am not going there only to deliver a speech. I also want to hear others and meet them’.” The hall broke into a loud applause. And why not? In very simple words, he had enunciated the importance and meaningfulness of literary functions.

I have a picture of that occasion in my mobile in which he is seated by my side in the front row. A writer friend of mine had taken the photo on his mobile and mailed to me. I can’t remember his name now. When Mudrarakshas was sitting here, he felt the urge to use the toilet. He asked me, “Where is that person who came with me? I said, “I don’t know, but just tell me what you want.” “I want to go to the toilet”, he said. I helped him get up and took him to the toilet holding his hands. How helpless can one be with old age and illness!

I have a picture of that occasion in my mobile in which he is seated by my side in the front row. A writer friend of mine had taken the photo on his mobile and mailed to me. I can’t remember his name now. When Mudrarakshas was sitting here, he felt the urge to use the toilet. He asked me, “Where is that person who came with me? I said, “I don’t know, but just tell me what you want.” “I want to go to the toilet”, he said. I helped him get up and took him to the toilet holding his hands. How helpless can one be with old age and illness!

My last meeting with him was at Rai Auditorium, Lucknow, on 23 August 2015. He was there as the keynote speaker for the release of Ramswaroop Verma Samagra edited by Bhagwanswaroop Katiyar. By coincidence, I had the good fortune of sitting beside him at the function. I found that his health had deteriorated even further. He could not even speak properly. But he made it a point to attend the function as a mark of respect for Ramswaroop Verma. For people like me, who like to take rest even when slightly indisposed, he was an inspiration. He made some candid comments about Ramswaroop Verma, which warranted further discussion. But that did not happen. He said, “Verma was a key figure of his time who not only participated in politics but also made Dalit and backward classes aware of the evils of Brahmanism. But the movement he built to establish Arjak ideology lost steam soon. He was the forerunner of an ideology which was acutely needed today, but it is dead now. Why it did not last? Was Verma ji also responsible for it?” He did not elaborate further – maybe because of ill health, maybe because he did not want to antagonize the devotees of Verma, whose conduct was diametrically opposite to their leader’s ideology. When I broached the topic with him after the function, he could not hide his pain. He was very distressed that the Dalit and OBC castes had become the upholders of Brahmanism – which Verma opposed tooth and nail all his life.

Once I ran into Mudrarakshas at the Allahabad residence of Lalbahadur Verma. I do not remember the year but it was probably at the start of the new millennium. This meeting was important in two ways. One, because there I met Subhash Gatade, Vikas Rai and Ravindra Kalia for the first time and two, because I was witness to the conversation between Kaila and Mudrarakshas in which they shared their intimate memories. The conversation was interesting and was punctuated with long guffaws. We all shared the same ideology but Mudrarakshas was different from us in one major way. He was bitterly critical of the contemporary Left, which was not ready to battle caste consciousness. As always, he put forth his arguments forcefully and Vikas Rai supplemented it with an example.

That was the time when Mudrarakshas’ regular column in Rashtriya Sahara had made him a hero of the Dalit-OBCs. He was giving a sharp edge to the ideology of Ambedkar and Phule through his writings. He had taken the place of Chandrikaprasad Jigyasu, Lalaisingh Yadav and Ramswaroop Verma. He had become an ideal of the Dalit communities and had come to acquire a position no Dalit writer ever could. It was he who told the Hindi world that Rabindranath Tagore was born into a Chandal family but when he was given the opportunity, he became a world-renowned poet and Bismillah Khan, a Hela (Bhangi) by caste, became an internationally renowned Shehnai maestro. Vishwa Shudra Sabha, a Lucknow-based organization, conferred the title of “Shudracharya” on Mudrarakshas. No other writer ever got this honour. It is another matter that the Hindi literary world reacted very bitterly to this development and overnight branded him a casteist. But the ignoramuses did not know that this “casteism” was awakening the Dalit communities.

He was one of the few Hindi critics who had demolished the citadels of criticism and had done a re-evaluation of literature. This re-evaluation led him to declare Premchand anti-Dalit. He even said that had Premchand been there today, Dalits would have burnt him alive. He had to face opprobrium for this statement. Virendra Yadav had written a longish piece in Tadbhav chastising him. Probably around that time Sohanpal Sumakashar, president of Dalit Sahitya Akademi, Delhi had launched a campaign of burning Premchand’s novel Rangbhoomi. I was not in agreement with Mudrarakshas on this issue and of course, burning Premchand’s literature was stupidity of the first order.

Whatever might have been the original name of Mudrarakshas, whatever might have been his caste or Varna, the Bahujan society had accepted him as its ideal. That was why P.D. Tandon, head of Mau’s Chamar Samaj Parishad, had invited him as chief guest in the parishad’s national convention. The event was held on 9 April 2006 at Dadhi Chakki, Ambedkar Park, in Mau. Coincidentally, I was present as a special guest. This was one of my most memorable meetings with him. We were to travel on the same train on 8 April from Lucknow to Maunathbhanjan. This journey introduced me to his simplicity and I was able to see how he chose to remain an ordinary person – so much so that I felt very small before him. It was a summer evening and I was waiting for him on the platform. He was nowhere to be seen. The train arrived and I boarded the AC-II coach in which I had reservation. I rang him up (by then, he had started keeping a mobile) and asked where he was. “I am on the train”, he replied. “But you are not in the coach”, I said. I expected him to travel in the AC coach and the train had only one AC coach. He said, “I am in the sleeper coach.” I was taken aback. I asked him his coach number and went to meet him. There was this great writer, bathed in sweat, sitting on his berth by the window. The coach was dark and hot. I requested him to join me in the AC coach. “You just come along. I will arrange everything,” I said. But he was not ready. “I am fine here,” he said. When asked why, pointing at a person sitting opposite to him, he said, “He has been entrusted with the responsibility of escorting me. He has tickets of this class. So, I have to go with him and come back with him.”

The train was at Mau at the crack of dawn the next day. The programme was in the evening. Thousands had gathered to hear Mudrarakshas. That day happened to be the birthday of Mahapandit Rahul Sankrityayan. While speaking about Rahul Sankrityayan, he exposed the brahmanical character of Indian social system, quoting from the Vedas, the Smritis, the Puranas and other scriptures. The audience was mesmerized. Hearing him speak so fluently and so eloquently was a novel experience for me.

The same night, we had to catch a train back to Lucknow. We reached the station after having our dinner. The train was supposed to arrive at around 9 pm but it was running late by more than four hours. It arrived after 2 am. Due to power outage, the fans on the platform were not working. The heat and the mosquitoes would not let us sleep and we killed time strolling on the platform. We talked of politics and of literature and we also talked about our personal lives and our families. By that time, I had read his book Dharmashastron Ka Punarpath. I asked him, “Your theory about the Aryans is different from all others. You have written that only Brahmins had come to India from outside and that they had no intention of mingling with the original inhabitants. That was why they created a divisive social order and zealously protected their separate identity. But Dr Ambedkar’s theory is different. He considers Aryans as indigenous inhabitants of India. Had Ambedkar erred in understanding history?” Without batting an eyelid, he said, “Yes. Ambedkar had erred”.

In April 2011, I had sent a copy of my book Swami Achootanandji “Harihar” Aur Hindi Navjagran to him. He referred to it in his column in the Rashtriya Sahara of 3 July 2011. Dharamveer was livid after reading the review and wrote a long letter to Mudrarakshas. I am quoting from Mudrarakshas’s column, “A book titled Swami Achootanandji ‘Harihar’ Aur Hindi Navjagran by noted Dalit thinker Kanwal Bharti has come out recently. While writers like Bhartendu are being worshipped as the harbingers of enlightenment in Hindi, Kanwal has written a comprehensive and informative book on the life, works and thoughts of Achootanand that does a comparative study of him and other Hindi writers and thinkers. That part of the book is astonishingly balanced and thoughtful. It does not use abusive language like Dharamveer. Kanwal knows very well that criticism is effective only when it refrains from abuse.”

There is one more memorable event. It was the year 2005. Dalit Shodh Sansthan had organized a seminar in Rampur. Mata Prasad had consented to attend but the Sansthan’s president Dhiraj Sheel was unable to get in touch with Mudrarakshas. I phoned him and requested him to attend the meet. He was ailing. He told me, “Kanwal, I am not well but I will come to your city.” As soon as he consented, I got AC-II return tickets sent to him. On the appointed date, Mata Prasad and he reached Rampur. But a rainstorm ruined the function. People did not turn up and the event had to be cancelled. Mudrarakshas’s lunch was arranged at Dheeraj Sheel’s residence. The weather was so bad that it was not possible to take him anywhere in the city. Their train departed in the evening. We saw off both the personalities with a heavy heart. I could only thank him for accepting my invitation despite his poor health. Such was Mudra ji.