Bilara, 13 January: Generally, we travel to discover new places and meet new people. However, our travels end up being less about people, more about places. In fact, we travel to get away from people, surrounded as we are by a lot of them in our urban contexts. But when Pramod Ranjan came up with the idea of traversing the country to touch and feel the Bahujan traditions of the country, the rest of us at FORWARD Press sensed immediately what a meaningful pursuit that would be. And we agreed instantly. This trip would be more about people – the invisible people that make up the core of this nation – less about the enchanting landscapes that appear on tourism advertisements.

Since our colleagues at FORWARD Press, Sanjeev Chandan and Rajan Kumar, and Vishesh Rai, a JNU PhD scholar saw us off at India Gate, New Delhi, on a cold 5 January morning, we – Pramod Ranjan, Anil Kumar and Anil Varghese – have been on the road for 10 days and the trip has pretty much lived up to our expectations. We’ve finished Haryana and are almost at the end of our wanderings in Rajasthan. We’ve run into people who’ve been fighting the tide and those who have been thrown to the side by the tide.

What do you do when you lose your only son, when – and most probably because – you been standing up for the weak in society and providing for them? Crushed by grief, you wonder what you’ve done to deserve it. Then, hundreds of families from the bottom rung of society flee a village not very far from where you live after the dominant community burnt down their houses. They have sought refuge in your street. They come to your house for alms. Your wife, still mourning the loss of your son, musters up the courage to provide for them. The homeless women bless her and tell her she will soon give birth to another son. Shortly afterwards, she conceives and gives birth to a son. Overwhelmed by this unexpected provision, you welcome all those homeless families into your property. That’s where they have been staying since. They have been staying there for as long as your son has been alive.

We met such a man at the end of the very first day of our journey.

The families in question are Dalit victims of the infamous 2010 arson attack in Mirchpur and the man is Vedpal Singh Tanwar. A wall separates the area where the families live and Tanwar’s farmhouse. Disheveled children walk in and out of the swanky farmhouse like they belong there. It has a swimming pool too but it lies unused. Tanwar had already spent lakhs on the water purification system but couldn’t live with the idea of cooling himself off at the pool while his guests across the wall sweated it out in the sweltering heat of Haryana summers. Even then, the regular water supply is not nearly enough. He has to buy water – which is delivered in tankers. He runs up a monthly electricity bill of more than a lakh. This has been the story every month through the last seven years.

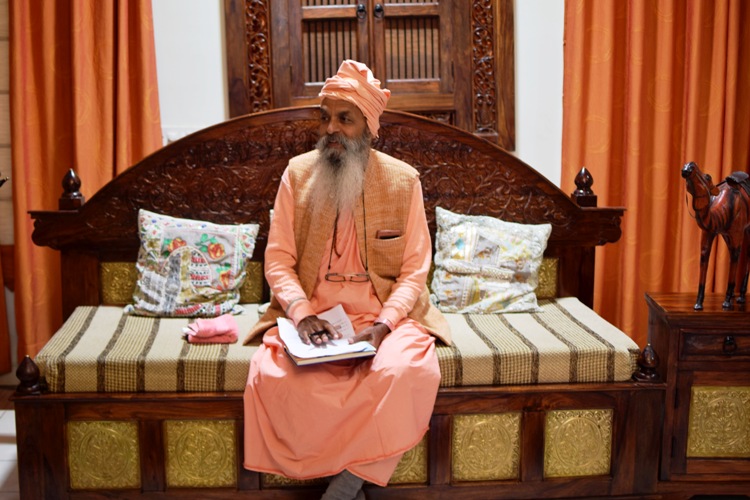

A refuge (ashram) from casteism?

There are some things that money can’t buy. Tanwar couldn’t bring back his only son with all the wealth at his disposal. Instead, he got another son at a time when he least expected it.

At Gogaji Medhi, on 7 January, we saw women falling flat on the ground and dragging themselves back up at regular intervals on their way to the temple. They too desired something that was beyond them. Others had apparently done the same and got what they wanted – usually an offspring, maybe a son, or relief from an illness or a snakebite. We also saw men performing the ritual as their near and dear ones walked beside them. Unlike most other traditional places of worship in the country, this Medhi (more like an ashram than a temple) has throughout its history welcomed people of all castes and even Muslims. That’s what drew a former medical doctor to the temple. Despite being a rationalist, who in private dismisses all the supposed supernatural powers at work in this temple in Rajasthan, he has accepted a responsible position on the temple trust. His mission is to gradually rid society of casteism and all superstitions – including those that make people throng Gogaji Medhi.

We stayed overnight at the temple ashram, where a hospitable young man from Madhubani, Bihar, attended to us. He had come to the temple in Rajasthan in the late Nineties – “Hum toh bas mazdoor kar rahe he” [This is just our livelihood], he said. All the 10 people employed in the temple kitchen are from his village.

Living amidst our Harappan heritage

We met another young man from Bihar employed by a wealthy Sikh man in Kalibanga, the place where remains of the Indus Civilization were excavated almost half a century ago. The Sikh man, who was a young father, landlord and businessman, graciously hosted us at his house. His minimalist yet plush house stood on a patch that was like an island in the middle of vast swathes of green wheat fields. He drove us to the Kalibanga excavation site. We saw the work of the hands of people who had lived more than five millennia ago: broken pottery, bangles strewn over mounds of earth and parts of brick walls tucked away underneath. Among the things excavated were their own script and a cultivated field. We discussed with our host the sheer ingenuity of our ancestors. Even the tenants farming his fields have dug up ancient pottery, so have a lot of the other local farmers. His own house might be sitting atop a part of Harappa.

Our host had everything going for him, lacked nothing materially, yet there was sadness in his life he couldn’t hold back from us. He had seen had his mentally unstable father shoot his wife and daughter (our host’s mother and sister) before tragically meeting his own end. Religion offered him some solace. His conversations with us usually revolved around either Guru Nanak and the Gurugranth Sahib or disillusionment with the government. That his village is named after his great grandfather or that the area in Hanumangarh district where he lives is a Sikh stronghold were mere digressions.

We went to bed that night mulling over his predicament. Early next morning, we bid goodbye hoping that our visit had eased his pain a bit.

Caste continues in Ramdevra, Jaisalmer

Our next stop, on January 8, was Ramdevra, a village that is home to a temple that is now a curious mix of Rajputana and Sufi (Islamic) traditions. There were tombs of the Mahants, each with the engraving of a warrior on a horse. There was plenty of the Sufi green all around, on the walls and the silk used as a covering for the drums. The priests were Brahmins and the trustees were Rajputs. Ramdev, now Rajasthan’s most popular deity, and his followers settled Ramdevra. He founded the Kamadiya cult that was free of all sorts of discrimination and picked and trained members of the lower castes as his disciples.

We met one of the trustees of the temple, Veerpal Singh, who claimed his lineage to Ramdev. He appeared to be in his thirties or early forties. He said the temple was open to people of all castes and faiths. However, his stand on casteism was unsettling to say the least. He said he couldn’t possibly impose casteism on people in cities but caste rules were still followed in his village home. Ramdev’s blood might run in his veins, but his values clearly don’t.

The next day, while visiting the Jaisalmer fort, we tried imagining a city that didn’t exist outside the walls of the magnificent sandstone structure until the early Eighties. The architecture of the fort, built in the 1100s, remains impressive. While the structure has been preserved, so has the caste composition of the fort population. Even today, the official residents are mainly Rajputs and Brahmins.

Incredible India?

From the fort, we followed the tourist trail to a village called Sam, about 40 kilometres away. It has become popular for its patches of sand dunes. Tourists take camel rides on the sand dunes and spend the night in tents. While the locals rent out their camels for the camel rides and open little tea shacks, their lives have yet to reflect this newfound source of income. We cooked our own dinner next to one of those shacks. A boy in his early teens, possibly the shack owner’s son, didn’t know the name of his country’s prime minister. Clearly, the ubiquitous Narendra Modi hasn’t been seen around here.

We had turned into tourists for a day, taking in the sights and posing for photos. We had become gullible too, believing the tourist guides when they told us that Sam offered a glimpse of the desert Rajasthan is known for. The next day, though, we would travel to Tanot, on India’s border with Pakistan, and be in for a surprise. There, we would get a chance to dig deeper into the struggles of those who plough on in the sands and, for a night, even experience it first-hand. More on that in the next post.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)