Santram B.A. (14 February 1887-5 June 1988) was one of those great personalities who devoted their entire lives to the cause of building a casteless and classless society. He came from the Kumhar caste and was one of the most talked-about writers of his time. His articles, published in magazines like Chaand, Sudha and Saraswati, sparked big debates. He launched a magazine titled Kranti in Urdu. He was also the editor of Bharatiya, the magazine of the Jalandhar College for Women and Vishwa Jyoti, published by Vishveshvaranand Vedic Sansthan, Lahore.

He was popular among his peers. His lifelong friendship with Rahul Sankrityayan speaks of his affability. It was probably in the first decade of the last century that Rahul met Santram in Lahore for the first time. Rahul’s first travelogue was published in Bharatiya, which Santram edited. Rahul was an Arya Samaji saint when he met Santram. He had not attained fame yet as a writer. Later, when he became Rahul Sankrityayan from Ramodar, he wrote a very touching reminiscence of Santram, which formed part of his book, Jinka Main Kritagya. He wrote, “His home was at Purani Bassi village near Hoshairpur, where he lived along with his wife in a house surrounded by a garden. He was blessed with a daughter at the time when I was living there. I was astonished by the stamina of his Punjabi wife. In the morning, she had completed all the household chores and milked the buffalo. In the afternoon, we came to know that she gave birth to a baby girl. I became the purohit of the newborn’s ‘jat-karma sanskar’ and gave the little one her name – Gargi.” Rahul’s reminiscences tell us that Santram’s only son died young. Later, he had his own house built at Krishnanagar, in Lahore, and married a Maharashtrian woman after the death of his first wife. After the Partition, Santram lost his house in Lahore, though his ancestral village Purani Bassi remained a part of India.

It was at Purani Bassi that he was born on 14 February 1887. Santram became an Arya Samaji at a young age. However, the organization that brought him fame as an Arya Samaji was the Jaatpaat Todak Mandal, which he had founded in 1922. The same mandal had invited Dr Ambedkar to deliver the presidential address at its annual convention at Lahore in 1936. The speech that Ambekar had prepared for the convention was very critical of the Vedas and the scriptures, and many members of the Mandal did not agree with it. Ambedkar refused to edit the speech and ultimately, the mandal postponed its convention. Later, Ambedkar published the speech as a book, and thus came into being one of his most famous books, Annihilation of Caste.

Santram and his Jaatpaat Todak Mandal had drawn the attention of the entire nation. It received overwhelming support but the conservatives opposed it with equal vehemence. Among the opponents was top scholar Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’. Writing on “Varnashram Dharma Ki Vartman Isthiti” in Matwala (1924), he said, “Just as mere expression of sympathy for the Shudras can’t be the be-all and end-all of the duty of the Brahmins, world’s greatest scholar and extraordinarily brilliant Shankar does not become the enemy of the Shudras just because Jaatpaat Todak Mandal’s Santram says so. His rules of discipline for the Shudras might have been very strict, but they were in keeping with his times. I don’t see the utility of the evidence like ‘Jayate Varna Sankar’, which has been quoted to defend the Varna system, and I don’t see any need for the Jaatpaat Todak Mandal. Why did Santram and others establish the Mandal when Brahmo Samaj was already there? Why did they not establish a branch of Brahmo Samaj instead?” He even wrote that the Brahmins had framed tough rules for the Shudras because, “Their polluted spores would have made the blissful body of contemporary society ill. The members of the Mandal would have understood how Shudras would have harmed pure society, marching on the path to emancipation after freeing itself from all evils, had they been sacrificing or spiritual instead of divisive, authoritarian and arrogant, as they are. If, while putting up with so many sufferings, the dwij community, to save itself, imposed somewhat harsh discipline on the Shudras, it was nothing before the atrocities committed on the dwijs by the Shudras.”

This “revolutionary article” of Nirala is included in his compilation of essays Chabuk. It is indicative of the deep hostility of the Hindu community towards the Jaatpaat Todak Mandal. Many Arya Samajis also did not want Santram to run the mandal. Most of them, including progressive intellectuals like Gokul Chandra Narang, Bhai Parmanand and Mahatma Hansraj, due to their pro-Hindu beliefs, quit the Mandal to protest the decision to invite Ambedkar to chair its convention. Many among them, including Bhai Parmanand, later joined the Hindu Mahasabha. It was not without reason that contemporary Hindus were in favour of the Brahmo Samaj, which believed in caste, but were against Jaatpaat Todak (caste destroyer) Mandal. But despite the non-cooperation from the Arya Samajis, Santram did not disband the mandal. Instead, he conducted its activities on his own.

Santram wrote more than 100 small booklets advocating Hindu-Muslim unity and an end to caste discrimination. These booklets stirred up the Hindu community. He distributed these booklets for free. When he went for a walk in the morning and the evening, he kept some copies of the booklets in his pockets to give to those he met on the way. Hamara Samaj, a book of his that was published in 1948, is an eye-opener for Hindus even today. I read the book for the first time in 1975 and since then, I have kept it safely like a sacred scripture. I consider it a scientific Veda. If the Hindus were to hear its formulations, all the cobwebs in their minds would disappear. I would like to share some excerpts from the book:

“During the reign of Shershah Suri, a bania called Hemchandra (Hemu Bakkal), who named himself Vikramaditya, tried to establish a Hindu empire. He defeated Mughal armies at many places including Delhi but the Rajputs refused to join his army, saying that as Kshatriyas, they could not fight under a person of the lower Vaishya varna. The result was that Hemchandra was defeated by Bairam Khan. But the same Rajputs did not find it humiliating to be the Muslims’ slaves.” (p 226)

“Till a Dhed (an untouchable) of Gujarat remained in the Hindu fold, the protectors of the Varna system did not allow him to rise. But as soon as he became a Muslim and changed his name to Nasiruddin Khusro, he became the ruler of the land of the Khilji clan. As a Hindu, he could not have even touched, let alone looked at a Kshatriya woman; but after becoming a Muslim, he married Dewal Devi, the wife of Raja Karnarao.” (p 227)

“After the death of the mother of Maulana Mohammed Ali and Maulana Shaukat Ali, Bhai Parmananda went to their home to express his condolences. In the course of the conversation, the Maulana told Bhaiji, ‘Why do you people want to block the onward march of Islam by placing the roadblocks of Shuddhi and emancipation of the Untouchables in its path? You will never succeed in this.’ Bhaiji asked the Maulana why he was saying so. The Maulana replied, ‘Just look the Bhangan passing by. I can convert her to Islam and make her my Begum today. Do you or Malaviyaji have that courage? I can marry off my daughter to any Hindu after converting him to Islam. Can any Hindu leader do this? Can a Hindu leader of my status marry his daughter to my son? If not, then why are you blocking the progress of Islam in the name of shuddhi and emancipation of the Untouchables?’ (p 178-179)

“You may ask, when different Hindu castes can live together even while believing in the caste system, why the Muslims can’t live with the Hindus. The answer is that all kinds of lepers can live together – some may have lesions on their nose, others on their feet, still others on their fingers. They can live together. But a healthy person cannot live among them. Similarly, all the Hindu castes, which are suffering from the leprosy called the caste system, can live together but the Muslims, who are free from this disease, cannot agree to live with them. The dwijs have crushed the self-esteem of the Shudras. The Shudras do not even feel the humiliation they suffer at the hands of the dwijs. But the Muslims resent it.”(p 237).

Santram’s book is full of such instances.

On 16 January, 1996, I referred to the contribution of Santram in the paper I read at the national convention of Jan Sanskriti Manch in Allahabad. Sudhir Vidhyarthi liked it and told Santram’s daughter Gargi Chaddha, who lived in Delhi, about it. She wrote an inland letter to me on 20 March 1997 from her home at 51, Navjivan Vihar, New Delhi. In the letter, she gave a touching description of her mental state. “Bhaiyya, truly speaking, I felt great inner happiness to know that at least there is someone who remembers my father’s sacrifice and his selfless social service. I am his only living child but he never differentiated between me and others who loved him. Whosoever believed in his Jaatpaat Todak thoughts was his darling. You must be aware that this selfless man spent his entire life in struggles and revolts and faced deprivations – all to free this country from the very dangerous ailment of caste discrimination. Uprooting this system was the only objective of my life, he used to say. He got little in life except the title of a rebel. He used to say, “Chala Jaooanga chhodkar jab is ashiyane ko, wafayein tab yaad aayegeen meri is zamane ko.” (After I have left my this abode for good, the world will remember my dedication.)

At the end she wrote, “I wanted that before my eyes, his articles, which are as useful today as they must have been then, should be published in the form of a book. I tried but did not succeed. You are a good writer. You may succeed.”

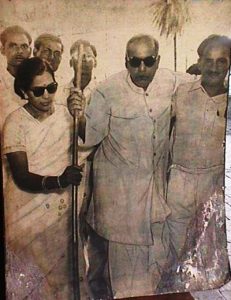

I received the second letter from her on 17 April 1997. She gave me two new pieces of information, which deserve mention. She wrote, “Till 1991, my husband Bhimsen Chaddha (who is not with me and has gone to be with my father), worked hard to further my father’s mission. The way he served my father for five years was matchless. Venerable Vishnu Prabhakar ji used to say that by the way Panditji was served, even gods would have felt jealous.” She also wrote that he was honoured by the Sahitya Academy at a function at Ravindra Bhavan when he turned 100 in 1987. A year later, on 5 June 1988, he breathed his last at his daughter’s home.

Gargi ji had contacted many big publishers for publication of the innumerable articles of Santram, but none evinced any interest. She must have been very hopeful that I would be able to get it done. I did try but due to her failing health, she could not make the material available to me. Later, I lost touch with her. She was so ill. I don’t think she would be alive now.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, literature, culture and politics. Next on the publication schedule is a book on Dr Ambedkar’s multifaceted personality. To book a copy in advance, contact The Marginalised Prakashan, IGNOU Road, Delhi. Mobile: +919968527911.

For more information on Forward Press Books, write to us: info@forwardmagazine.in