During the Independence movement, many diverse and competing perspectives emerged to form the “idea of India”. The Congress emphasized liberal democracy and secular nationalism. The Left stressed the inclusiveness of secularism to advance the interest of the working class. Hindu nationalists championed brahmanical nationalism, represented by Hindutva ideologues, and members of the Hindu Mahasabha. Dalitbahujan thinkers, on the other hand, put forward principles that could help achieve an egalitarian society, including the betterment of socially oppressed groups and the most marginalized sections of society.

Given this backdrop and the imminence of the Lok Sabha elections, the Dalitbahujan alliance formed before Uttar Pradesh by-polls recently assumes significance. Dalitbahujan politics has the “political ingredients” to contain the might of “Hindutva juggernaut”, provided the Samajwadi Party (SP)-Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) alliance incorporates the values of secularism and idea of fraternal social justice. The March 2018 by-polls are a case in point, in which the SP-BSP alliance defeated the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party-Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (BJP-RSS) combine in Gorakhpur and Phulpur Lok Sabha constituencies. Given the present political situation nationwide, if the leadership of the BSP and SP takes seriously the radical legacy of Dalitbahujan thinkers such as Phule, Periyar and Ambedkar, it has the potential to challenge the BJP-RSS combine.

We know from experience that “Mandal Politics” is accompanied by “Mandir Politics” (Kamandal politics) in north India. Scholars have observed that whenever Bahujan assertions have taken place, Hinduvta politics has also risen to construct the so-called larger identity of “Hindu unity”. That is what happened at the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 by the RSS and the VHP (Vishwa Hindu Parishad).

Discourse on social justice

Political scientist Gopal Guru says there are two different traditions concerning social justice in the Indian context. First one is known as the orthodox tradition, which focuses more on governing and disciplining rather than enabling. Second one is the heterodox tradition, which tries to define social justice through radical interrogation of the caste system and existing social hierarchies (Gopal Guru, “Social Justice”, in Niraja Gopal Jayal and Pratab Bhanu Mehta ed, The Oxford Companion to Politics in India, New Delhi, OUP, 2013).

As an eminent social scientist Harish S. Wankhede rightly observes, post-Ambedkarite social and political movements have not achieved Ambedkar’s idea of social justice. Citing the case of Maharashtra and UP, Wankhede in his article, “The Social and the Political in Dalit Movement Today” (Economic & Political Weekly, 9-15 Feb 2008), points out that while in Maharashtra, Dalit masses after their conversion to Buddhism succeeded to some extent in creating a democratic, social and cultural space for themselves, they couldn’t lay their hands on political power. In Uttar Pradesh, Kanshi Ram and Mayawati’s Dalit politics propelled BSP to power four times, but was not able to strengthen the culture of Dalitbahujan consciousness among the marginalized groups. Wankhede writes that Ambedkar had proposed two dynamic strategies to meet these challenges: a religious-conversion movement to challenge the hegemony of the social elite by establishing secular fraternity and an alliance of Dalits with other marginalized sections. Wankhede adds that only a fraternal social system is conducive for bearing the fruits of social justice.

Similarly, critical theorist and feminist scholar Nancy Fraser has said that there is an urgent need to combine the both “politics of recognition” and “politics of redistribution” to achieve the broader agenda of social justice in the age of identity politics ( N. Fraser, “From Redistribution to Recognition: Dilemmas of Social Justice in the Post Socialist Age” in Cynthia Wilett, Theorizing Multiculturalism: A Guide to the Current Debate, Blackwell, UK, 1998).

In other words, the SP-BSP alliance must incorporate “fraternal social justice” in its scheme of things, including both the material as well as the symbolic, rather than only focusing on electoral tactics and social engineering to capture state power.

SP-BSP alliance and social justice

The emergence of Dalitbahujan political discourse has given rise to a new “political culture” in India. That is why social scientist and now full-time political activist Yogendra Yadav has seen the rise of “lower-caste” politics as the “second democratic upsurge” in north Indian politics. Noted French social scientist Christophe Jaffrelot has described the Bahujan assertions, mainly after the implementation of Mandal commission report in 1992, as a “silent revolution” in north India. Prof Rajni Kothari has argued that post-Mandal Dalitbahujan alliance has strengthened the processes of secularization in Indian politics. More importantly, the process of “politicization” of lower castes has widened the “culture of democracy” (Rajni Kothari, “Rise of the Dalits and the Renewed Debate on Caste”, Economic & Political Weekly, 25 June 1994).

Bahujan leader Kanshi Ram used to say that to replace Hindutva politics, it would be crucial to unite the Bahujan masses (SC, ST and OBC and minorities). He thus formed and established first the BAMCEF (The All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation in 1978), Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti (DS-4 in 1981) and finally Bahujan Samaj Party (1984) at the national level to bring about a “cultural revolution”. Like Ambedkar, Kanshi Ram also stressed that the sociopolitical conditions of Bahujan masses couldn’t be improved unless they as a “political community” captured State power.

But it is a sad commentary of our times that in the name of Mandal politics, a few castes have benefited much more than the other castes among the OBCs and the intra-group inequality has increased. As Jaffrelot says, when Lalu Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav became chief ministers of UP and Bihar, respectively, they used the issue of reservations as a political ploy to promote their own caste and family interests rather than democratizing the intra-caste social relations among the Bahujan masses. (Christophe Jaffrelot, India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India, Permanent Black, New Delhi, 2014).

Bahujan politics has failed to ensure that the beneficiaries of the Mandal commission reforms are representative of the various Bahujan communities. That is how communal and feudal forces pounced on the opportunity to politically exploit those castes and social groups that have not been benefited under SP and BSP rules. It has also become imperative for the SP-BSP combine to talk not only about “quota politics” but also fight crony capitalism and communalism to bring about “fraternal social justice”.

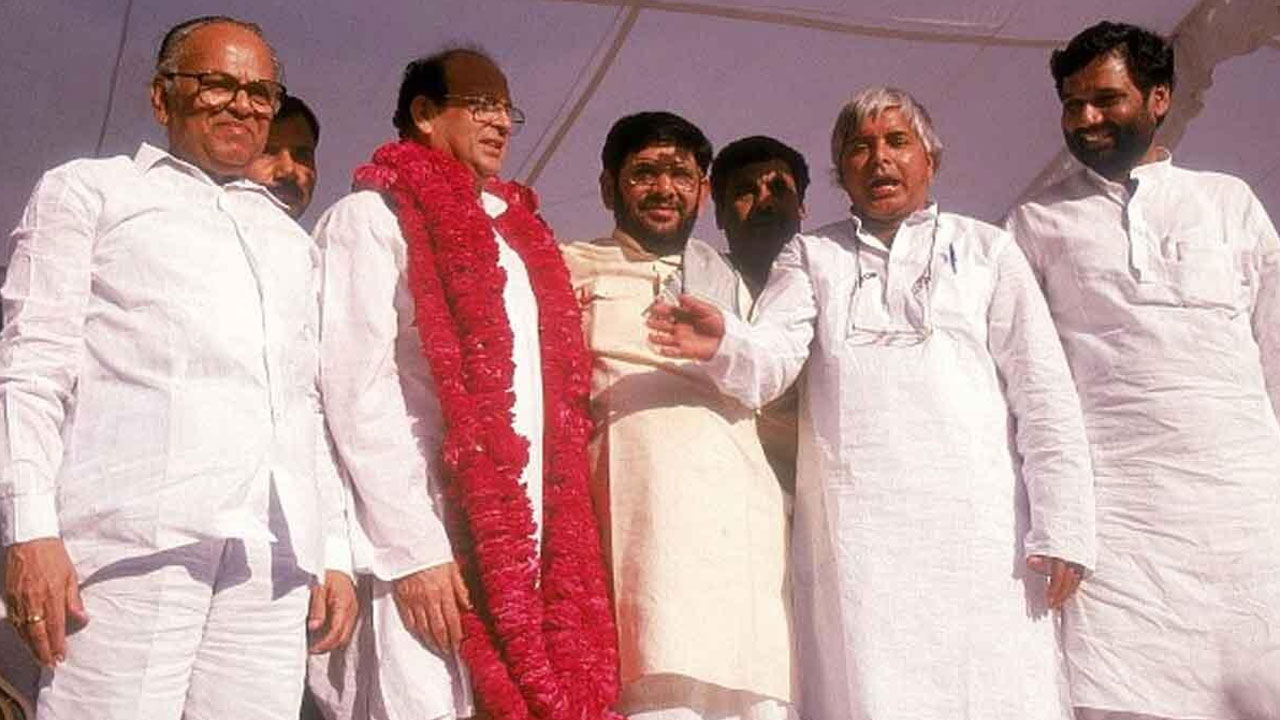

Around the time of Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, Bahujan leaders like Mulayam Singh Yadav and Kanshi Ram had successfully contained the Hindutva juggernaut by uniting Dalitbahujan masses behind popular political slogans like “Mile Mulayam Kanshi Ram, Hawa mein ud Gaye Jai Shree Ram” (Mulayam and Kanshi Ram have come together, blowing way the cries of ‘victory to Ram’) and winning elections. It is high time today’s Dalitbahujan drew a political lesson from that experiment.

The SP and the BSP have between them ruled UP for more than 20 years, yet caste and communal strife continues unabated. These parties, which claim to stand for social justice, have completely failed the victims of communal violence, for example, even those of the relatively recent Muzaffarnagar riots. The SP has compromised on secular politics and has not clearly stated its opposition to Hinduvta. The BSP even joined hands with the BJP to form a government in UP in 2002. Due to their ambiguous political stand with respect to the Hindutva forces in the past, both SP and BSP have utterly failed to unite the Bahujan masses at the grass roots. Taking its cue from the radical socio-cultural movements of Maharashtra, the SP-BSP alliance must also tirelessly work on the cultural front to counter the RSS-BJP programmes of sanskritization (having the so-called “lower castes” emulate and adopt the culture, rituals and lifestyles of the upper castes) based on its agenda of samajik samrasta (social harmony) and to try to bring about social and political unity among the Bahujans.

Hindutva politics on social justice

Jaffrelot points out that the RSS has always had an upper-caste character and that the Hindutva ideology relies on the “brahmanical view of society”. It publicly upholds the cause of the upper-caste. (C. Jafferlot, India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India, Permanent Black, New Delhi, 2014).

For instance, in 1990, when prime minister V.P. Singh announced the implementation of recommendations of the Mandal Commission, the RSS immediately opposed the move. Even the BJP’s manifesto for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections did not mention the word “reservation”. The manifesto emphasized samajik samrasata instead. On several occasions, the RSS and the BJP have openly said that the government should review its reservation policy. To put it simply, the BJP-RSS concept of social justice is not based on the principle of justice and equality. One could argue that the BJP-RSS’s concept of social justice is based on the “orthodox tradition” (represented by mostly the upper castes and brahmanical forces) rather than “heterodox tradition” as found in the writings of Phule, Ambedkar and Periyar. This is not suprising because most of the RSS officebearers are upper-caste males, particularly from Brahmin castes. Noted historian Ananya Vajpeyi writes, “Under a government of the Hindu Right, India is witnessing yet another phase of reaction and orthodoxy, a return to medieval brahmanical values that seek to monopolize rights for a select few and turn everyone else out of the body politic.” (‘The reactionary present’, The Hindu, 6 October 2015)

The past four years of the Modi government has seen many communal and caste incidents mainly perpetuated by the goons of the RSS and its affiliate, Bajrang Dal. Ghar wapsi (bringing back people of other faiths to Hinduism), violent opposition to “love jihad” (Muslim men marrying Hindu women), beef ban, violence against women, caste atrocities, attacks on minorities and vandalizing of statues of Bahujan icons continue unabated.

The 2017 annual report of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has data on the cases registered under the SC/ST (PoA) Act. In 2014 there were 40,401 of these cases; they had dropped marginally by 4.3 per cent to 38,670 in 2015, but had increased by 5.5 per cent to reach 40,801 in 2016. In 2016, Uttar Pradesh reported 4,816 cases of rape – among the highest in the country. In October 2017, during Muharram, communal clashes took place in Kanpur. On Ambedkar Jayanti in Saharanpur, in April 2017, BJP MP Raghav Lakhanpal took out a procession without police permission, and raised slogans like “UP mein rehna hoga, to Yogi-Yogi kehna hoga” (If you want to remain in UP, chant ‘Yogi-Yogi’) and “Jai Shri Ram”, passing through areas home to mostly Jatavs and Muslims. After this march, a major clash between Thakurs and Dalits broke out, leading to 60 Dalit houses being burnt down. Over the decade to 2016, the rate of crime against Dalits rose more than eight times (746 percent); there were 2.4 crimes per 1,00,000 Dalits in 2006; the figure rose to 20.3 in 2016 (Alison Saldanha & Chaitanya Mallapur, FirstPost, 5 April 2018).

The BJP governments at the Centre and in the states have clearly failed to achieve the Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s stated goal of “Sabka Sath Sabka Vikas” (Development for All). His government has not taken a firm political stand against the dilution of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989 despite a series of incidents – including Rohith Vemula’s suicide, the flogging of Dalits in Una, the Saharanpur violence and the arrest of Bhim Army leader Chandrashekhar, the violence in Bhima Koregaon in Maharshatra – necessitating such a stringent Act more than ever.

The road ahead

The BJP-RSS’s agenda of samajik samrasata and promises of development have proved hollow in the three years since May 2014, when they took over the reins of the govermment at the Centre. Like with the Dalit Panther movement of the 1970s, Ambedkarite politics today has moved beyond the realm of “identity politics” and incorporated the agenda of substantive issues like land rights, employment, education and health. At this juncture, it is crucial that the SP and the BSP seek Ambedkar’s insights and draw lessons from the last four years of Bahujan protests against Hindutva politics. Their alliance assumes significance especially at a time when national parties like the Congress and the Left are in decline and have failed to challenge the BJP electorally. Given its recent successes in the recent UP by-polls, and since winning UP elections holds the key to being a serious contender at the national stage, the alliance has political potential as long as it adheres to the broader agenda of social justice pursued by Dalitbahujan icons.

The politics of the alliance should go beyond identity-related issues and incorporate larger issues like land rights, education and health, women’s rights, labour and peasant rights, minority rights and privatization. Ambedkar’s philosophy of social justice had a broader and more radical vision, with both Brahmanism and capitalism in its crosshairs. Kanshi Ram had advocated land ownership for Dalits and the backward classes. To politicize the Bahujan masses, his BSP in the 1990s famously coined the slogan “Jo Zameen Sarkari Hai, Woh Zameen Hamari Hai” (Government-Owned Land is Ours).

Bahujan leaders have long believed that the principal contradiction in Indian politics is between Manuwad (Brahmanism) and Manavwad ( Humanism). Ambedkar’s idea of fraternal social justice can be achieved only through an alliance against the brahmanical social order. It is possible if SP, BSP and other like-minded forces rise above their narrow concerns.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen