“You turned away your face, became a stone, took much much more, gave much much less/ the country died, you remained! You turned out your loving father, you shooed away your compassionate mother, you kept terrier dogs of self-interest, you gave up the duties enjoined upon you by emotions, you smothered the intentions of your heart, you broke the forehead of mind/ you tore apart the limbs of arguments, you got stuck, you got jammed, you got caught, you got sunk in your own slush! You sautéed reason in the oil of selfishness, you gobbled up ideals, what did you do up to now, what kind of life did you live/ took much much more, gave much-much less/ the country died/ you remained …”

This is a rough translation of the lines from Muktibodh’s classic Andhere Mein. Dinesh Murar, who adapted the poem into a film, is no more. The untimely demise of this alert sentinel of society and Dalit research scholar has benumbed his friends and colleagues. He was admitted to the Sevagram Hospital in Wardha on the evening of 17 July, following blood pressure-related problems. Unexpectedly, he succumbed to a brain haemorrhage. He was one of those persons who always had their finger on the pulse of society, waging personal struggles and the struggles of the Dalit-OBCs simultaneously. Murar’s friends tried to convince him that despite all internal contradictions, all the darkness around, we have to learn and, survive in this society. He had imbibed the lesson partly but he passed away when he was needed the most.

Murar, who had been awarded his PhD by the Department of Mass Communication at the Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Viswavidyalaya, was enrolled in a post-doctoral research project. He is said to have struggled without a fellowship for a while but eventually he was granted one. The poem ‘Andhre Mein’, which Dinesh Murar filmed, depicts the social condition of the Indian middle class. The middle-class guilty conscience finds expression in the lines “Zindagi nishkriya ban gayee talghar” (life has become inactive, consigned to the basement). It is a poem about the desire of doing something and the agony of being unable to do it. An umbilical cord connects the middle class to the ruling class and the former is perennially involved in hatching conspiracies on the latter’s behalf. The middle-class intellectuals are also part of this conspiracy and their ghost procession passing through the night can be seen in the poem. The power structure will not spare the middle class. The power structure will kill its beliefs by entangling it in a trap. The poem has the imagery of the killing of an artist and a thought. This is the background of the poem in which the people and the people’s poet play their respective roles.

Dinesh Murar’s colleagues took the body of their beloved friend to a village near Hinganghat, about 40 kilometres from Wardha, where his last rites were performed. That evening, his close friends, scholars from both the Department of Mass Communication and rest of the University organized a condolence meeting. “We have lost a good human being and a talented scholar. Murar was pursuing post-doctoral course with an ICSSR fellowship,” said the university in a condolence message. “The university sends its deep condolences to the grieving family.” The pain of Murar’s demise was felt outside the university too, especially in Vidarbha’s academic circles. At the condolence meeting, research scholars from the Department of Mass Communication said that Murar was a symbol of committed and objective journalism and his death was a big loss for the department. The department and university wished the Murar’s near and dear ones all the strength to bear the pain of his loss. Several teachers and peers paid tribute to Murar.

Sanjeev Chandan, who knew Murar closely and was a fellow ideologue, said, “Does someone depart like this? A phone call from Dheeraj Kamble, giving the news of your demise, woke me up today morning. You are still at the Sevagram Hospital. The doctors are trying to find out the reason for your death. But my brother, you have gone beyond all this. You are very well aware about the difficulties that shatter the dreams of poor parents, when their brilliant son, the son doing post-doctoral research, passes away. I remember the great bond between us. I can remember the time when we literally ended up on the street, having taken on the university administration. You were not active in the agitations but were with us.”

Murar was among the founding members of the Ambedkar Students’ Federation. “We are deeply pained,” said the federation. “A brilliant and hard-working student is not among us. He wrote consistently on contemporary issues. He actively participated in the activities of the organizations. This is a big loss for his family, for us and for society. We are with his family at this time of grief.” Murar was very popular in the university campus. “The passing of Dr Dinesh Murar, our senior and a scholar committed to the research and study of journalism in Vidarbha and Maharashtra, is like the disappearance of a golden future,” said Sandeep Verma. “His efforts to bare the social concerns (of lack of them) of journalism and his pragmatic approach were the hallmarks of his excellent work.”

Life and research

Dinesh Kushabrao Murar was 37 years old. He was born on 22 July 1981 into a poor Dalit family of Kachan village in the Hinganghat tehsil. His pursuit of higher studies in journalism had brought him to Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya, where he was awarded his MA in 2009, MPhil in 2009 and PhD in 2014.

His PhD thesis was titled “A study of the social background of journalists”. This was new terrain for the media, especially in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. His research raised some serious questions. He categorized journalism in Vidarbha on the basis of the social background of the journalists and their writings. He showed how a particular line of thought dominated journalism and how the background of a journalist influenced his writings. Murar discovered that not only in Vidarbha but in the entire country, established newspapers and magazines were dominated by journalists who had a specific social and religious background. His research also confirmed a skewed gender ratio in the newsroom. Professor Kripashankar Chaube, Murar’s research guide, says he was a diligent researcher and his post-doctoral research, which was meant to be a “Sociological study of caste-centric Marathi films”, would have brought many new facts to light.

Murar leaves behind his parents, a brother and a sister.

Translated by Amrish Herdenia

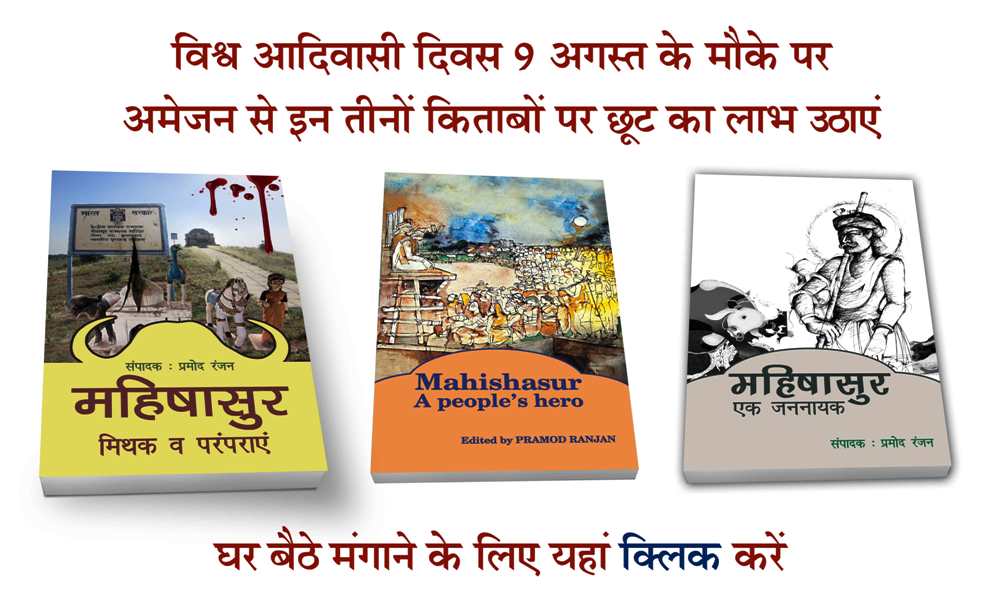

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History