“You lost your prestige and that of our family when this low-born boy scored more marks than you.” The low-born boy in question is my father. My father was telling me about an incident from his school days. That is how his friend’s father had scolded his friend. My father had stood there trembling in fear. When he should have been exulting in the news of topping the entire region, my father was numb with fear. His crime was that he was born an Adivasi and yet had excelled in academics!

I was born into an Adivasi family in a village where upper castes were dominant. My father, a topper in his school, was always asked to sit apart from the non-Adivasi, upper-caste boys. The teachers, however, were impressed by him. They guided him and supported him. He also cultivated good life-long friendships with Brahmin students.

He walked every day to his college 18 kilometres away so that he didn’t have to rent nearby accomodation. Then, no one was willing to rent out a room to a skinny, dark-skinned Adivasi boy. He got a job as a “general candidate” and was posted far away from his home district. All his working life, he assumed the identity of a Rajput so that he could rent a house to stay in. He never opted for the Constitutional provision of reservations to avoid the label and the caste-based discrimination associated with it. He was well respected by colleagues and superiors for being a hardworking, honest and caring man.

Every morning, my mother never failed to hammer into my head that “I am a Rajput and should say so whenever someone asked about my caste”. One day, someone spilled the beans and everyone in my father’s office took turns to verbally abuse him, using the filthiest of expletives. Suddenly, there was no respect or the adoration.

The colony boys stopped playing with us. I knew something had gone wrong. I asked my father, “What is Jati [caste]”? He sighed, “Jati wahi he jo kabhi nahi jati [Jati is something which never goes away]”.

In college, I got a new identity, “Siddu” – a nickname originating from the word “Scheduled” used for students belonging to the reserved category. Students and teachers alike – those who prided themselves for not belonging to the reserved category, of course – used the nickname casually. Our resistance to this daily discrimination and exposure to knowledge turned us into the ‘Dalit’, the comradeship of the downtrodden.

How can the word “Dalit” ever be illegal or amoral? Well, I guess that depends on what one takes the word to mean. A word is the smallest unit of meaning in speech or writing, but its weight and significance is disproportionately massive. Words not only hold the past but also the future in them, the memories of the past and aspirations for the future. “Dalit” is certainly not just one another word.

Kancha Ilaiah, the scholar who belongs to the Other Backward Classes (OBC), explains the evolution of the word Dalit. The word Dalit comes from the Pali word “dal” (दल). As in “kamal-dal” (lotus pod), “dal” means a “group of closely knit things”. Going by Pali grammar, the word “Dalit” comes from Dal + It (दल + इत्). If we look at some homophonic words, for example, “damit” (दमित), “shoshit” (शोषित), “shobhit” (शोभित), “rakshit” (रक्षित) and “patit” (पतित), and deconstruct them, we will see that the “it” (इत) here means “to have or to be part of”. Thus Dalit connotes “being part of a dal” (being a member of a group or a tribe).

“History repeats itself first as tragedy, second as farce,” said the Marx. Like all the names given to the fallen people, the Aryans probably gave the name “Dalit” to people beyond the pale of caste and to the non-Aryan tribes. Dr B.R. Ambedkar said the Depressed Classes were made up of the broken, defeated tribes. Even today the word “Dalam” denotes a group of wandering tribal people. In ancient times, who were these wandering people? Who defeated them? Who broke them? Were the legendary “Anarya” dispossessed, defeated, despised and denigrated by the marauding, invading Aryans? With the aid of new technology, the truth is slowly but surely being revealed, provided we are willing to open our eyes and ears to it. Dalits are narrating their long forgotten stories, scattered across the ages.

“History is a nightmare, from which I am trying to awake” said James Joyce. Today, there is a perceptible awakening among the “Depressed Classes”, which has found expression in all spheres of life. There is this urge to reclaim the lost prestige and identity. An assertive section of Depressed Classes has identified themselves as “Dalits”. The word “Dalit” has never before been opposed by these communities, as it connotes a sense of self-empowerment, self-respect, solidarity and pride. This word which came into existence with its negative usage has evolved into a symbol of hope.

The recent government advisory outlawing the word “Dalit” is ill-advised, ill-conceived and mala fide in nature. Why frame a law which you cannot execute? The government has no business taking a call on what we call ourselves. The bureaucratic parlance is up to the government but it absolutely mustn’t be thrust on us.

There is every reason to believe that this advisory also has a contemporary sinister political subtext. The Hindutva project does not believe in a just and equitable society: Scheduled castes and tribes, women, poor peasants and minorities can exist but as second-class citizens.

Copy-editing: Anil

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

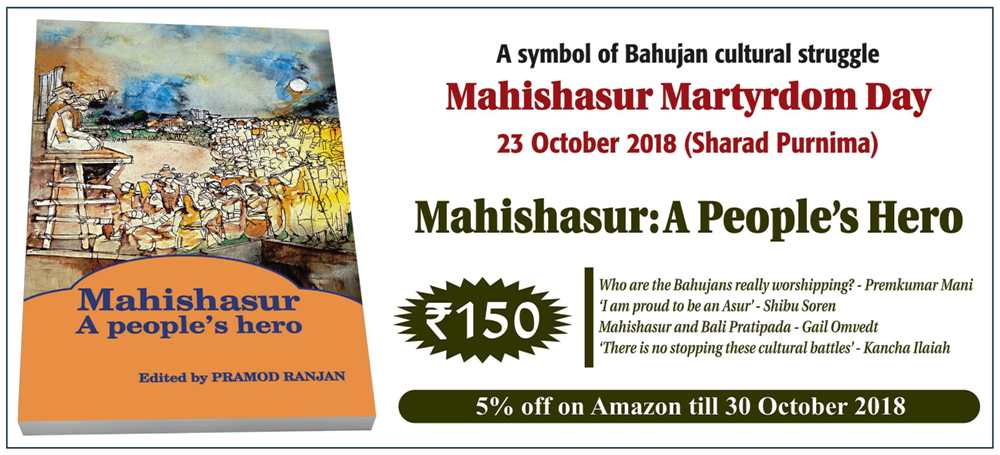

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen