Bhagat Singh, all of 23, and his associates Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged by the British colonists on 23 March 1931. Three years before his hanging, in June 1928, Bhagat Singh’s article appeared in a newspaper called Kirti under the penname “Vidrohi”. That article, subsequently, was republished under the title “Achhoot Samasya”. The contents of the piece indicate that ideologically, Dr Ambedkar and Bhagat Singh had meeting points.

However, let us begin with the canards being spread by extremist elements in social media. Though such canards rarely pass the test of truth and fact-checking they can and do create a smokescreen, howsoever fleeting it may be.

It is often asked if Dr Ambedkar was such a great lawyer, why did he do nothing to save Bhagat Singh from the gallows? Why he did not defend Bhagat Singh in the courts? Faced with such questions, the common man is bound to agree: why Ambedkar did not use his legal acumen to save the life of Bhagat Singh. Could Ambedkar have fought the case of Bhagat Singh and his associates? Could he have saved the revolutionaries from the gallows?

At the time, Ambedkar’s activities were mainly confined to Maharashtra. His legal profession was not his primary concern. His objective was to secure human rights to the Untouchables. He had already led the Mahad Satyagraha and the movement for entry into the Kalaram Temple. He was fervently raising the demand for a separate electorate for the Untouchables. Given the circumstances, he was not the usual lawyer. He was a sociopolitical activist. Ambedkar was in Mumbai when Bhagat Singh was being tried in Lahore and was represented by eminent lawyer Asaf Ali.

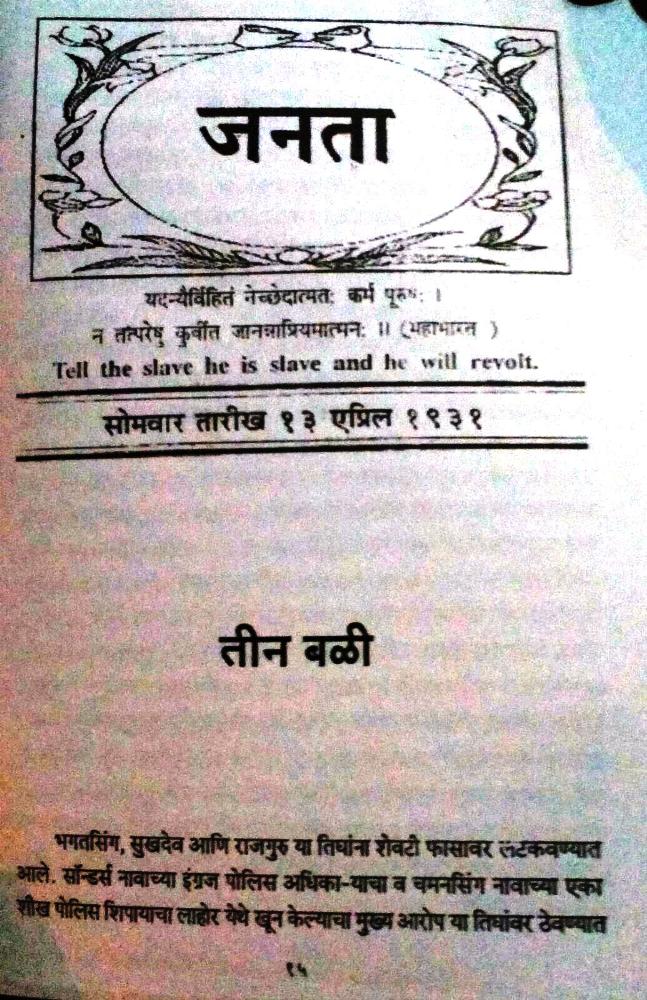

It is also claimed that Ambedkar did not pay tribute to Bhagat Singh on the latter’s martyrdom – which is not true. The editorial titled “Three Victims” in the 13 April 1931 issue of his newspaper Janata is proof.

Some Ambedkarites are also adept in spreading rumours. It is suggested that Bhagat Singh wrote in his seminal article ‘Why I am an Atheist’, that if he was not hanged, he would devote his remaining life to promoting Ambedkar’s mission. Bhagat Singh didn’t write any such thing.

However, let us steer clear of unsubstantiated claims and baseless allegations and turn to the commonalities between the thinking of Bhagat Singh and Ambedkar and how both dreamt of an egalitarian India.

We all know that Ambedkar bared the real face of the varna-caste system of Hinduism and its hypocrisy and said the Hindu scriptures should be dynamited. Bhagat Singh also did not hold back when it came to admonishing the Hindus for their unscientific beliefs.

Also read: ‘Three Victims’ – Ambedkar’s editorial on Bhagat Singh’s martyrdom

Bhagat Singh had written his article “Why I am an atheist” at the Lahore Central Jail in 1930. It was published first by The Peoples newspaper on 25 September 1931, leading to the government banning the newspaper. In this article, Bhagat Singh addresses the Hindus directly. He writes, “You, the Hindus, would say: Whosoever undergoes sufferings in this life, must have been a sinner in his previous birth. It is tantamount to saying that those who are oppressors now were Godly people then, in their previous births. For this reason alone they hold power in their hands. Let me say it plainly that your ancestors were shrewd people. They were always in search of petty hoaxes to play upon people and snatch from them the power of Reason.”

He also launched a frontal attack on the concepts of soul and the Almighty, Heaven and Hell, rituals, religious superstitions, narrow-mindedness and obscurantism. Like Ambedkar, he too mercilessly exposed the hypocrisy intrinsic to Hinduism and called for its complete elimination. In his article, “Achhooton Samasya” he asks, “We Indians boast of our spiritualism, but then, we avoid accepting every human being as a fellow being like ourselves …We are seriously debating whether to permit the Untouchables to wear the janeu or to read Vedas/Shastras. We often complain about our maltreatment in other countries. The British rulers don’t consider us equals to the British subjects, but do we have a right to complain?”

He does not stop here. He quotes from a 1926 speech by Noor Mohammed, a member of the Bombay Legislative Council, and expresses his complete agreement. “If Hindu society refuses to allow other human beings, fellow creatures at that, to attend public schools … what right have they to ask for more rights from the bureaucracy? … how can we ask for greater political rights when we ourselves deny elementary rights of human beings?

When, in the thick of the Freedom Struggle, the issues of Dalits started being raised, the leaders of the movement tried to brush them aside saying that this was an internal matter of the Indians which they would resolve after Independence. However, Ambedkar insisted that his men were slaves of the slaves of the British and that the issue of their emancipation should be resolved alongside the issue of freedom from British rule. Ambedkar was fighting for the emancipation of the community who were the doubly-enslaved. Bhagat Singh also unequivocally supported them. Both Ambedkar and Bhagat Singh wanted political freedom to be accompanied by social transformation. They held similar views.

Bhagat Singh flays the savarna Hindus in no uncertain terms. He writes, “Even a dog can sit on our lap, it can also move freely in the kitchen but if a fellow human being touches you, your dharma is endangered.” Similarly, Dr Ambedkar says in Annihilation of Caste that for the Hindus, purity and pollution are only about kitchens and marital relations. He also castigates the Hindus for treating Untouchables as worse than animals and exposes the hypocrisy behind the scriptural sanction to the concepts of soul and god and heaven and hell.

Bhagat Singh and Ambedkar never met but they thought along the same lines. On 25 December 1927, Ambedkar burnt the Manusmriti and sought special privileges for the Untouchables, which later took the concrete form of a separate electorate. In June 1928, supporting the demand for more rights and a separate electorate for the Untouchables, Bhagat Singh wrote, “We regard their [Untouchables’] recent uniting to form their distinct identity, and also demanding representation equal to Muslims in legislatures, being equal to them in number, is a move in the right direction.” He adds, “Either reject communal representation altogether, else give these people too their due share! Let them have their own public representatives who would demand more rights for them.”

It is clear that had Bhagat Singh been alive at the time of the signing of the Poona Pact, he would have supported Ambedkar. In any case, Bhagat Singh had thoroughly exposed Madan Mohan Malaviya, the Hindu leader who had signed the Poona Pact on behalf of Gandhi, in his “Achhoot Samasya”. He wrote, “We have great leaders like Madan Mohan Malaviya who claim to be great upholders of equality; they go to meetings, embrace Untouchables in public, go home and have a bath with their clothes on. If this sentiment continues, we can’t fight untouchability.”

Flaying the two-facedness of Hinduism, he writes, “Instead of being grateful to them for the services they provide, we mistreat those whom we called Untouchables. We insult those who do the work which is considered menial and lowly to facilitate us. We can worship animals but cannot seat a human being by our side.”

That is what Dr Ambedkar also said in his writings and speeches. Dr Ambedkar contends that the Untouchables are valiant communities and so does Bhagat Singh. He writes, “Know your history. None but you were the muscle of the army of Guru Gobind Singh. It was on your strength that Shivaji could do what he did and for which he is still alive in history. Your sacrifices have been inscribed in golden letters.”

Like Ambedkar, Bhagat Singh dreams of an egalitarian society. He rejects the antiquated customs and superstitions of Hinduism and insists that it is education that can lead to the emancipation of the Untouchables. He talks about their political rights and calls upon them to organize. Dr Ambedkar brings the “Riddles of Hinduism” to light and urges the Untouchables to educate, organize and struggle. Thus, both the great men envisaged an India based on reason and science.

Alas, Bhagat Singh didn’t live long. Otherwise, he would have joined hands with Dr Ambedkar to build an India that would definitely have been better than the India of today.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History