There are a great many stories that have yet to be told about the Indian statesman and advocate for social justice, Bhimrao Ambedkar. For my part, I have chosen to focus much of my time over the past nine years to tell a story that I think needs to be told in greater detail – that of the relationship between Ambedkar and his American teacher, the pragmatist John Dewey. Most acknowledge the influence of Ambedkar’s education on his insightful, original, and powerful writings and speeches, but we know too little about what he heard or was excited by during the years at Columbia University in New York, or in London.

While writing my book on Ambedkar and Dewey, The Evolution of Pragmatism in India (HarperCollins India, 2023), I have come across tantalizing hints of an Ambedkar we may have overlooked, an Ambedkar that extends beyond what he wrote on the page – and beyond the uses we may make of him in our own writings. It is of Ambedkar the human, the person with a personality. Capturing this side of Ambedkar is extremely difficult, since so much of what remains in our image of the great thinker and statesman is based on the words he left on the page or the actions recounted in our biographies. These are invaluable, but they too rarely give us insight into the person and personality of this great figure.

Finding Ambedkar, finding a personality

As I read through Ambedkar’s now-decaying notes and books he left behind, I keep finding myself intrigued by the chance and challenge to get “inside” such a great thinker’s personality. Written works are meant for certain purposes, and specific audiences of hearers or readers. They are meant to do something in that situation. Thus, they tell us what an individual might be interested in. Do they tell us about that individual’s enduring and semi-consistent personality, if there is such a thing residing below our various actions and utterances? Perhaps. Or is it a mistake to think that our self and personality are set, and just simply there to be revealed in any or all stages of our life?

Our actions make our personality, but they also reveal it. This dialectic holds for Ambedkar’s own actions while he sat there reading books, either during his education in the West or in his lifelong reading in his own library. I’ve paid attention to every mark Ambedkar has made in all of his personal notes, books, and letters, as I believe these reveal something about the reader. Many might think that such ephemera don’t capture the real importance of his thought. But what might they show us? Could they reveal a side to him that we’ve overlooked?

The importance of John Dewey for Ambedkar’s personality

I am convinced that John Dewey mattered greatly for Ambedkar’s thought. Some scholars that I’ve conversed with wonder why I would spend so much time focusing on one teacher – Dewey – when Ambedkar had so many of them. Indeed, Ambedkar would list out many of these figures in the Columbia Alumni News in 1930: “The best friends I have had in my life were some of my classmates at Columbia and my great professors, John Dewey, James Shotwell, Edwin Seligman and James Harvey Robinson.” Notice, however, that Dewey is the first name that Ambedkar presents to the readers of this newsletter. This represents the position that I’ve come to in my book – that Dewey was one of the leading, if not the leading, intellectual lights from Ambedkar’s education.

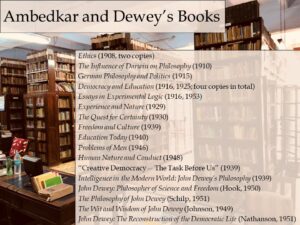

With Dewey, I see a level of engagement evident from Ambedkar that’s hard to replicate with any other figure. Judging from what remains of his library in various Indian archives, Ambedkar owned more books by or about Dewey than by any other contemporary author or teacher – including his advisor, E. R. A. Seligman, or intellectual foil, Karl Marx.1 Most of his Dewey books are heavily annotated, a feature that not all of his massive library shares. And in these books, one can get a better grasp on what he read, appropriated, or disagreed with after his time with Dewey at Columbia University concluded.

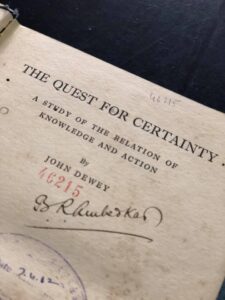

A large cache of these books are preserved at Siddharth College.2 Others have mined this collection to show his reading in areas of contemporary history and politics, but I have largely focused on the books on pragmatism. In one trip to peruse the dusty pages of these books made sacred by Ambedkar’s ownership, I noticed something I had earlier passed over. Ambedkar owned a book by John Dewey, The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy, that was published in 1910. The book was important for Dewey because it was where he worked out the importance Darwin’s theory of natural selection had for patterns of philosophy – approaches that sought out changelessness and certainty in a world that was contingent and changing in all of its aspects.

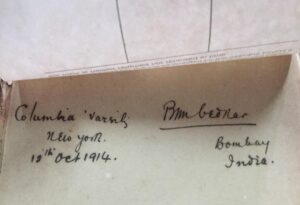

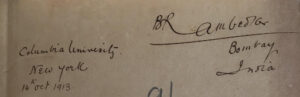

But this book held out another promise – it could show us more, if only a bit more, about the personality of its owner, Ambedkar. How did we know he owned this particular book? Hidden under a library information slip glued into the book was his signature and place of acquisition, a fairly common notation among his Columbia-era books and some of his books from London. We see written in his own pen notations of “Columbia / New York / 12th October 1914” and his signature – what appears to be “BAmbedkar / Bombay / India”.

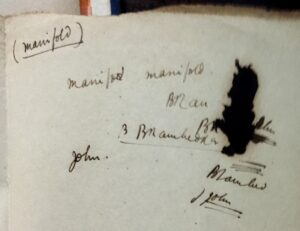

This book is interesting about what it tells us about Ambedkar beyond its many annotations and underlinings. Folded in the back of this text is a fragile piece of paper with a large ink blot and what appeared to be practice marks with one of his many beloved fountain pens.

For many trips to Siddharth College, I had largely ignored this sheet of paper. On this last trip, however, its possible messages and meanings began to speak to me more. While it cannot tell us about which argument in Dewey’s book – or Dewey’s whole body of work – Ambedkar loved or hated, it can tell us something about Dewey and, conversely, Ambedkar’s own personality. Looking at the scrap of paper, one immediately sees Ambedkar’s signature iterated partially or completely at least four times.

One also sees the word “manifold” penned out three times, most likely related to the appearance of this term of art from page 218 of Dewey’s book on Darwin. You can also see the word “John” penned out twice. Given these incomplete details, it’s no surprise that I, as well as others, would surely note with curiosity this sheet and then move on. It simply does not fit the assumed mould of what we’re looking for when we dig for scholarly evidence. We are so focused on what he argued, what he thought of the arguments of others, and his use in our own arguments about political theory or issues such as caste oppression that such incomplete scratches proffer no usefulness. They hold little meaning in the game of ascertaining and making arguments and claims about abstract matters.

But if one appreciates them for they may portend about Ambedkar the student, one’s mind may race. Here was Ambedkar the student, practising his penmanship on terms that Dewey used – manifold – that are rarely used outside of translations of Immanuel Kant’s mind-bending phrasings of how the human mind works. In other books, we see him practise an allied tactic of underlining complex or technical words and writing their meaning or synonyms in the margin. His approach to learning was engaged and active. He cared about what and who he was reading.

What of the signatures, though? One sees Ambedkar the student carefully attending to one of the most visible traces of his identity that survives his death – his unique and flowing signature. A signature is both unique as the person signing, an instance or symbol of their personality, and a mere incomplete representation of who they are. We are what we sign, but we are also so much more than those marks.

For anyone who spends their time perusing his letters and books, it’s obvious that Ambedkar’s signature was a work in progress. It changed over time, and like his cursive writing, grew more elaborate when he had the time and motivation to devote to it. His middle initial – “R” for “Ramji”, the forename of his father – does not seem present in the compressed signature at the front of the Dewey book on Darwin, acquired on 12 October 1914. The practice sheet shows him working diligently and repetitively on his personal signature, to the point where the “R” becomes distinct and present.3 One sees the difference that such efforts make when they see his handwritten annotations to Charles Horton Cooley’s 1912 book, Social Organization.

Cooley, an important theorist in the emerging field of sociology, was a student of Dewey’s while both resided at the University of Michigan in the 1890s. Cooley would get his doctorate there while Dewey was preparing to head to greener pastures at the University of Chicago. But Dewey’s idealist reading of ethics and psychology made its mark on Cooley, and then later, Ambedkar. Ambedkar purchased this book almost a year earlier than the Dewey book on Darwin, and his signature shows more space between the letters and a flowing grace that was absent from the 1914 signature.

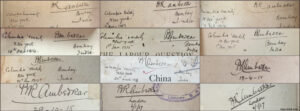

The evolution of a signature – and a personality

Ambedkar was so dedicated to his image that he practised his signature repeatedly; looking at the collage of all his early signatures from the time he arrived in New York to the end of his first trip to London, we find that he refined and stylized his signature. He cared about how he was seen through this mark, and perhaps more importantly, he cared about how this externalized representation of him, or his personality, appeared once he marked it on the page in front of him.

It also mattered that these signatures appeared on some of the most precious possessions for Ambedkar, no matter his age – his books. In his youth, his father Ramji pawned family valuables to allow for Ambedkar’s needed school books, and at the end of his life, Ambedkar died surrounded by thousands of books in Delhi – and was cremated a short distance from the tens of thousands of books entombed in his custom-built house, Rajgraha, in Bombay.

The books and their markings matter for what sense we make of Ambedkar. They show that he cared about how he was perceived by others, as well as how he thought he was presenting himself – self-respect was an integral part of his view of how one gains respect from others. Refining and revising his signature was an important part of his reconstruction of his identity through his Western education; he was becoming an individual with style, grace, and with a marked respect for knowledge. Indeed, it was his name that proudly marked so many of these books purchased early in his education at Columbia. Later on in life, he would continue to refine both his signature and his self image.

One also sees in these markings the mark of agency from Ambedkar the signer—it takes a certain belief in one’s own worth and value to mark a book as yours, potentially forever. Whereas any mark may convey ownership, the act of practising and refining one’s personalized signature indicates a care and efficacy in the signer. Ambedkar was partly his mark, his signature, and Ambedkar the agent would wilfully or effortfully make this mark – and perhaps his personality in a larger scope – even better through refinement, reconstruction, and cultivation.

The progress and care we see in the changing signature – and the practice and experiments that lay behind it—show us a driven personality, but one that is not without care and preparation. We also see something else that ought to strike one as curious on this practice sheet inserted into the Dewey book purchased in 1914. As we know from Ambedkar’s transcripts, the courses he took from Dewey were in the Fall 1914 semester (Philosophy 231: Psychological Ethics) and during the whole year of 1915-1916 (Philosophy 131-132: Moral and Political Philosophy). As we can see in the note paper presumably from October 1914, Ambedkar was apparently busy doodling John Dewey’s name alongside his perfunctory attempts to understand Dewey’s book (as evidenced by the “manifold” reference) – and next to his own efforts at refining his personalized signature.

What can we make of all of this? Ambedkar was not in the habit of writing the names of authors he read, either in the books he owned or in any notes that I’ve found. We can see something of the focus and intense admiration for Dewey by the fact that Ambedkar was repetitively writing his first name, most likely during the first few weeks of his initial face-to-face meeting with Dewey in a Columbia seminar room. This, to me, is important: Ambedkar undeniably purchased a book by the sage of American pragmatism while attending Dewey’s lectures, and most likely marked that scrap sheet while taking Dewey’s course. This means that something about that book and author affected him enough that he annotated it, as well as practised his penmanship with his name – and Dewey’s – while trying to digest Dewey’s novel approach to topics in ethics, politics, and truth. Dewey was on his mind, and his paper.

In a vivid, and aesthetically charged sense, the doodles and practice markings connected to this Dewey book purchased shortly after Ambedkar started his fall semester at Columbia in 1914 confirm the later reports that there was something about Dewey’s embodied personality that grabbed Ambedkar. As K.N. Kadam recounts, “Dr Ambedkar took down every word uttered by his great teacher [Dewey] in the course of his lectures; and it seems that Ambedkar used to tell his friends that, if unfortunately Dewey died all of a sudden, ‘I could reproduce every lecture verbatim.’”4 In 1952, Ambedkar traveled to New York to receive an honorary degree from Columbia. Before he could get there, John Dewey passed away. In a letter known by virtually all familiar with Ambedkar’s biography, he wrote to his wife, Savita, upon learning of Dewey’s death that “I was looking forward to meet[ing] Prof Dewey. But he died on the 2nd when our plane was in Rome. I am so sorry. I owe all my intellectual life to him. He was a wonderful man.”5

These laudatory words and claims are unique in Ambedkar’s writings and letters; nowhere else does he make such a claim about any other Western teacher from his past, whether it’s about the genesis of his “intellectual life” or whether it refers to his impersonation skills. Parts of Dewey seeped into Ambedkar’s psyche in a deep way, and the image of Dewey as embodied pragmatist thinker undeniably served as a sort of role model to imitate – and to transcend in certain respects – when Ambedkar pursued his unique course of self-creation and activism once back in India. What I have noticed – after years of visiting and perusing these same books – are some of the details that can add color and body to our ideas about Ambedkar the personality.

Signatures that matter

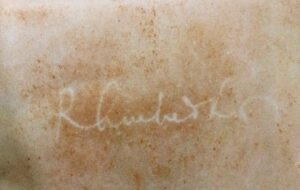

Beyond academic projects, Ambedkar’s image and signature matter for millions today in India. Witness the various honorific brandings of social media profile pictures with Ambedkar’s graceful signature from his later years.

Like his evolving and ever-changing signature, Ambedkar changed and evolved. But at the core of this human work-in-progress was someone who believed that he mattered. And this has helped his contemporary followers find ways to see that they matter.

Ambedkar, departing from a tradition that placed his value at less than zero, and that placed the source of this worth in debts incurred in previous births, believed that he mattered, and believed that thinking this way could make him matter—both in American classrooms like Dewey’s and back in India. Perhaps this seriousness with which he took his mission to struggle against caste injustice explains his usual serious or even dour expressions in most surviving photographs of him. Or perhaps his seriousness in so many photographs that still haunt our image of him was a surfacing of the serious commitment he had to a self – his self – that was subject to practiced and intentional reconstruction.

In these stray words and markings cursorily jammed in his 1914 purchase of Dewey’s Influence of Darwin on Philosophy, we see rare and easily overlooked hints that reveal more about Ambedkar’s personality than they seem to offer. They tell us there’s much to divine about Ambedkar’s intellectual relationship with Dewey, his pragmatist guru, as well as more to say about his belief that the individual matters and that his own powers of self-cultivation could see him through a lifetime filled with momentous accomplishments and crushing defeats. In finding his signature, Ambedkar found himself. Or better yet, in refining his signature, Ambedkar found a way to reconstruct himself.

References:

1 By my count, he owned over 20 books by or about Dewey that still survive in the remains of his personal library.

2 I must thank the librarians of Siddharth College, especially Shrikant Talvatkar and Chaitali Sonawane, who have given me their precious time and access to the Ambedkar collection at Siddharth College over many trips to Mumbai.

3 The presence or absence of Ambedkar’s middle name “Ramji” has also been the source of contest in modern times; see https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/lucknow/ramji-to-be-part-of-ambedkars-name/articleshow/63525310.cms

4 K.N. Kadam, The Meaning of the Ambedkarite Conversion to Buddhism and Other Essays (New Delhi: Popular Prakashan, 1997), 1.

5 Nanak Chand Rattu, Last Few Years of Dr Ambedkar (New Delhi: Amrit Publishing House, 1997), 35.