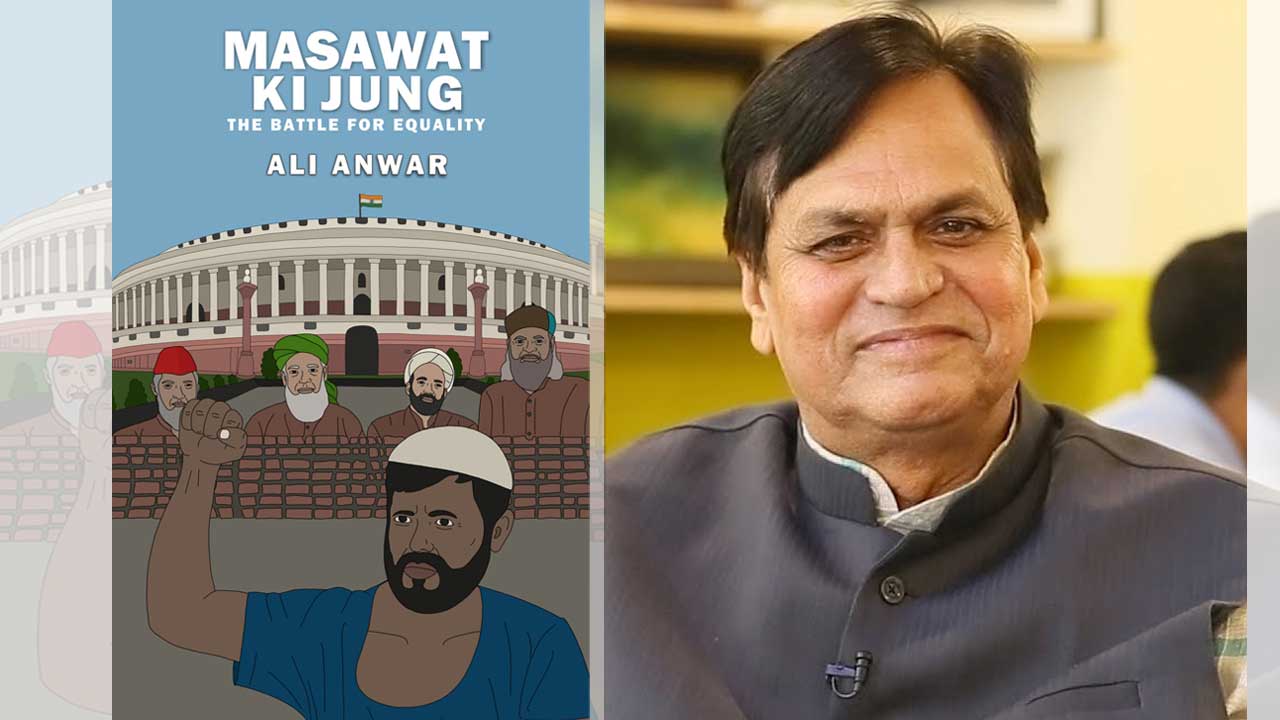

(The following is an excerpt from the book ‘Masawat ki Jung: The Battle for Equality’ authored by Ali Anwar and published by Forward Press.)

The East India Company first of all attacked the handicraft industry. The cloth manufactured here was exported to the rest of the world. The Company stopped this export and flooded the market with foreign cloth. Not only did they levy excessive tax on the export of Indian cloth and ruin the industry, they also tortured the weavers. They severed the thumbs of the artisans manufacturing the malmal of Dhaka, which was famous the world over. ‘East India Company ke forzondon ke nam’ is a famous nazam of Josh:

Loottay phirte the jab tum karwan dar karwan

Sar barhana[1] phir rahi thi daulate hindostan

Dastkaron ke angoothe kattey phirten the tum

Sard lashon se gadhon ko pattay phirte the tum

Sanate hindustan par maut thi chayi hui

Maut bhi kaisi tumhare haath ki layi hui

British historian and politician Thomas Babington Macaulay writes, “In spite of the Mussulman despot and of the Mahratta freebooter, Bengal was known through the East as the garden of Eden, as the rich kingdom. Its population multiplied exceedingly. Distant provinces were nourished from the overflowing of its granaries; and the noble ladies of London and Paris were clothed in the delicate produce of its looms.” [His essay ‘Lord Clive’ (1840)]

Among the Muslims, the weaver community had the largest population. This section had been facing humiliation in society for centuries. Then, the British came and drove this community to the brink of economic destruction as well. Political awareness was bound to come to this section. In the early 1910s, several forums began to be established. Since in those days Calcutta was the centre of all types of movements – educational, social and political – the foundation of the Momin movement was laid here. It is noteworthy that most of the leaders who laid the foundation for the movement here were from Bihar. Among them, Maulvi Ali Hussain aka Asim Bihari was at the forefront. The other people of Bihar who actively participated in this movement and led it were Maulana Qazi Abdul Jabbar of Sheikhpura (Munger), Abdul Hasan Sheikhpuri, Maulana Muhammad Yahiya Sasarami, Ali Ahmad Buland, Akbar Bhagalpuri, Abdul Hasan Bismil Aarvi, Hafiz Manzoor Hasan of Bettiah, Hafiz Shamsuddin Ahmad Shams of Maner, Haji Mohammad Farkhund Ali of Sasaram, Abdushams, Abdu Ghaffar and so on.

Asim Bihari, a resident of Khasganj mohalla in Bihar Sharif, soon became the leader and cornerstone of this movement. With his stormy travels and fiery speeches, he not only sent the message of the movement to Bengal and Bihar but also from Rangoon to Peshawar and from the hills of the Himalayas to Kanyakumari. Born in 1890 into a very poor family, Asim Bihari, after his primary education, went to Calcutta to earn a living at the age of 16. There, he joined the Usha Company. He started spending time on studies after work. This was the era of the Khilafat movement, in which Bihari became involved. After the arrest of the Ali brothers, he started organizing the meetings of their mother B. Amma. After participating in the movement, there was no way he could find a job. Therefore, he started making beedis in Calcutta. Here, he found a whole team of like-minded young men. Then he came in contact with leaders like Gandhiji, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar. These leaders were present at a function of the Jamiatul Momin held on 10 September 1921 at Tantibagh, Calcutta. Earlier, in the month of April, he had launched a newspaper from Tantibagh named Al-Momin. Asim Bihari had good command of Urdu, Arabic and Farsi, but he knew very little English.

Asim Bihari was very popular among the beedi workers and poor, backward sections of society. Several people knew him as Kamali Baba. He would use the common man’s language in his speeches, which was easy for the illiterate to understand. He always tried to include backward and Pasmanda Muslims apart from the ansari in the Momin Tehreek (Movement). Like a good organizer, he would remain behind the scenes and always encourage new people to rise in the organization. He regularly advocated that the Momin Conference should always maintain its independent existence and vision and should never become the B team of the Congress. He was of the view that personal honesty and a sacrificial spirit are essential qualities of a social and political worker.

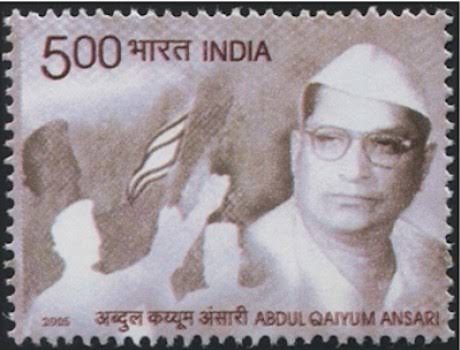

During 1946 Provincial Assembly elections, he had differences with Abdul Qayum Ansari and other momin leaders. He supported a few Muslim League candidates, but soon he realized his mistake. Hence, after organizing three-four meetings in support of the League candidates, he backed off. But only because of this one mistake, he was lost in the political darkness forever. In December 1953, he died in Atala, Allahabad, and was buried there. Abdul Qayum Ansari had immense respect for him and regarded him as an elder brother. Qayum Ansari belonged to a well-fed, happy, middle-class family, but Asim Bihari was born into a very poor family, and what Bihari did for the backward and dalit Muslim is unparalleled. Perhaps, because he didn’t know English and suffered from asthma, he trailed in the political race.

Until 1937, the Momin Conference was a social organization. The following year (1938), it began to take the shape of a political organization. Soon after the establishment of the Momin Conference, so-called upper-class Muslims vehemently opposed it. It is noteworthy that just when a new awareness was developing among Dalit Muslims, the Muslim League, under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, demanded a separate country for Muslims (Pakistan) to distract the attention of the Dalit Muslims from the real issue. The Nawabs, landlords, the wealthy and the ashraf supported this demand of the Muslim League. The backward and Dalit Muslims did not show any interest. But it hurts to think that our national leaders did not grasp the importance of a new force emerging among Muslims and instead accepted the demand for the division of the country under the pressure of Muslim League. In this context, the remark of Kingsley Davis is relevant – “The partition of the region into Pakistan and the Union of India was the admission of final defeat so far as the Muslim conquest of India is concerned.”[2]

Such was the foresightedness of Abdul Qayum Ansari that he could already sense the ill effects of India’s partition. Therefore, he stood firmly against the Muslim League. In 1946, the Momin Conference entered politics as a political party but it took steps to ensure there was no division of the nationalist vote. This was the reason it entered into an alliance with Indian National Congress and shared seats. After the election, when the state government was being formed in Bihar under the leadership of Shri Babu [Shri Krishna Singh], Congress leader Maulana Abul Kalam Azad agreed to give a seat in the Cabinet to Abdul Qayum Ansari on the condition that he first dissolve his Momin Conference and sign the membership oath form of the Congress. But Mr Ansari and other Momin leaders of that period refused. At last, Congress leaders had to relent, and Qayum Ansari was made Cabinet member while remaining in the Momin Conference. Another famous momin leader of Bihar was Ahad Mohammad Noor.

Qayum Ansari and Noor together had Shri Babu’s government establish 500 backward Muslim welfare schools and 1200 weaver cooperative societies. Even in colleges, provisions were made for free education of hundreds of momin students, and seats were reserved for them in medical colleges. Abdul Qayum Ansari could get so much done probably because from the early years of his political career he had stayed in touch with national leaders, particularly Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. He wrote regularly to Nehru and other leaders apprising them of the problems of momin community. In reply to his letter of 30 October 1937, Jawaharlal Nehru replied, “I entirely agree with you in your remark that certain upper-class groups among the Muslims have more or less dominated the Muslims in India, much to the disadvantage of others. This applies even more so to the Hindus, as you will know, where some Upper Caste groups have dominated vast numbers of other people. The problem is essentially similar in both cases.”[3]

Nehru adds in the same letter, “This domination has been cultural, educational etc but essentially it has been economic. A group which is economically in a bad condition, usually deteriorates culturally and educationally and is exploited by others.”

The Muslim League was not only canvassing to divide the country communally but was also demanding that Bihar be divided in the same manner. The leaders of Muslim League knew that Qayum Ansari clearly understood their tricks. Therefore, they targeted him and declared him an enemy of Muslims. K.K. Dutta writes, “A section of the Muslim League was demanding the division of Bihar. They suggested the need to carve out a Muslim region comprising Purnea, South Bhagalpur, South Munger and parts of Gaya – Jehanabad, Nawada sub-division and a part of the central sub-division. The Bihar Muslim League conference was held in May 1947 in Kishanganj. Raja Ghazanfar Ali presided over the conference. Apart from criticizing the Bihar government, a proposal to merge Purnea, North Bhagalpur, North Munger and Santhal Pargana with Bengal was accepted. Moreover, Jamiat-ul-Ulema, Ahrar Party and other Non-Muslim parties were declared the enemy of the Muslim community and they were issued a strong warning. People like Abdul Qayum Ansari, who had joined the Congress government in Bihar, were called enemies of Muslims, and Muslims were urged to beware of him.”[4]

If the provincial government formed in 1937 wished to do anything for the development of momins, the Muslim League opposed it. Dutta writes, “After the Muslim League conference in Sheikhpura [Munger] another conference was held on 23 April 1938 in Gaya. The Congress Cabinet came under scathing criticism. There was anger particularly against the literacy movement and Muslim contact campaign. The sanction of Rs 10,000 made for the development of the momin community was criticized saying that this was an attempt to create a rift in the Muslim community.”[5]

But there were two organizations in Bihar who had the courage to strongly oppose the Muslim League. These were Jamiat-e-Ulema and Momin Jamiat. On 25 June 1929, in Darbhanga, a demand was issued on behalf of the momin community that half of the reserved seats for the Muslims be given to the momin community. A rally was held in Bettiah in July 1938 by Jamiat-e-Ulema and the activities of the Muslim League were strongly criticized.

In Bihar, under the leadership of the Muslim League, the so-called upper-class hoisted the Pakistani flag but the momins opposed the act and hoisted the national flag. K.K. Dutta writes, “On 19 April 1940, Pakistan Day was celebrated in different places of Bihar. As part of these celebrations, the Lahore proposal for the partition of India was read and accepted. On the other hand, Ahrar Party and momins opposed it.”[6]

Following the partition and India becoming independent on 15 August 1947, the Momin Conference restricted its political activities and decided to remain a social organization. But unfortunately, this movement became weaker and weaker until it really became the B team of Congress. Moreover, some people with momin names became yes-men to Congress leaders and started exploiting the people of their own community as the ‘handloom mafia’. All the villages of weavers in the state turned into graveyards of handlooms. The artisans began migrating to other states in search of livelihood. Those hands, which used to weave fine cloth, are now pulling rickshaws in the cities. After Qayum Ansari, there was no one to raise the voice on behalf of this community. When we look back at this misery since Independence, Ranchi-based Dr Ahmad Sajjad’s comment feels appropriate: “The coffin of this soulless movement, having passed on from one shoulder to another, has now been buried in a few houses of Delhi and other cities. Every five years, at the time of the general elections, the leaders of momins become active and change the cloth on this coffin and offer flowers and incense sticks. Then a few fortunate among them are offered ministerial posts at the state or central level and chairmanship and membership of assembly councils.”[7]

[1] Meaning ‘uncovered head’.

[2] Kingsley Davis, ‘The Population of India and Pakistan’, Princeton University Press, 1951, p 191.

[3] See the complete letter written by Jawaharlal Nehru in English in the appendix [of the book].

[4] K.K. Dutta, ‘Bihar mein Swatantrata Andolan ka Itihas’ (History of Freedom Struggle in Bihar), Vol 3.

[5] Ibid, p 321.

[6] Ibid, p 325.

[7] Dr Ahmad Sajjad, ‘Tehreek All India Momin Conference Tarikh ke Aaine Mein’, Ranchi.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)