Management theorist Peter Drucker rightly said, “Only what gets measured gets managed.” After the approval of the Union Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) to include caste enumeration in the forthcoming census, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) notified on 4 June 2025 that it would carry out the long-awaited decadal census in two phases, using 0000 hours on 1 October 2026 as the reference (point at which the population is frozen for purposes of the census) for Ladakh and snowbound areas of Jammu & Kashmir, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and 0000 hours on 1 March 2027 as the reference for the rest of India. Although the notification did not mention caste census, the practice discontinued since 1931 will likely be brought back in response to the long-standing demand for empirical data to help shape more scientific and evidence-based affirmative action. The impending (caste) census has reignited the discussion around the sub-classification of the Other Backward Classes (OBC) reservation quota. Expansion and sub-classification of the OBC quota on the basis of the data from the caste census can transform the social justice processes providing representation and empower the most backward castes among the backward classes.

Sub-classification: A debate

The debate over sub-classification of the reservation quota for OBCs has been going on for decades, driven by the fact that OBC as a category is not homogenous and there is a need to distinguish between the castes within the category whose social and economic conditions are markedly different. The intent to subcategorize the OBCs as Backward Classes and Extremely Backward Classes was expressed in the recommendations made by the Appointments Department of the Bihar government in 1951, which drew up lists of castes under both categories. This was acknowledged and the lists were reproduced by the Mungeri Lal Commission in its report, submitted in 1976, with some changes. Acting on the commission’s observations, the then Bihar chief minister Karpoori Thakur provided 20 per cent reservation for the Other Backward Classes, subcategorized into Annexure I (Extremely Backward Classes) and Annexure II (Backward Classes), allocating 12 per cent and 8 per cent reservation respectively for them in government jobs. Karpoori Thakur then added 3 per cent reservation for women and another 3 per cent for the Economically Backward Classes.

The First Backward Classes Commission set up by the Union Government, that is, the Kaka Kalelkar Commission (1955), also identified the most backward communities among the OBCs.

On 31 July 1962, the State of Mysore (now Karnataka) issued a notification under Article 15 (4) of the Constitution for reservation of seats in engineering and medical colleges. The backward classes were divided into two categories, backward classes (28 per cent) and more backward classes (22 per cent). The same year, in the matter of M.R. Balaji v State of Mysore, the Supreme Court held that under Article 15(4), the sub-classification of the backward classes’ reservation was unconstitutional. In the matter of K.C. Vasanth Kumar v State of Karnataka (1985), the Supreme Court disagreed with its own earlier judgment in M.R. Balaji v State of Mysore, observing that under Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution, sub-classification is permissible only if some classes lag far behind others. The court reasoned that if only the more backward classes have access to reservation, the backward classes won’t be able to compete with the advanced classes in the general category.

In 1964, the Deshmukh Committee report recommended the following subcategories under Backward Classes in Maharashtra: 1) New converts to Buddhism; 2) Denotified, Semi-Nomadic and Nomadic Tribes and 3) Other Backward Communities. This subcategorization continues to date, although not precisely as the committee recommended.

In Andhra Pradesh, based on the Anantharaman Commission’s report (1970), the Backward Classes were divided into four subcategories: Group A consisted of aboriginal tribes, denotified tribes, nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes, etc; Group B comprised professional groups like toddy tappers, weavers, carpenters, ironsmiths, goldsmiths, etc; Group C had Scheduled Castes converts to Christianity and their progeny; and Group D was assigned for all other communities within the backward classes.

In Tamil Nadu, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government appointed A.N Sattanatham Commission in 1969, which observed:

“Nearly 70 percent of the population of the cultivating castes, i.e., Padayachi, Kallar and Maravar and a large percentage of the Valiyans, Ambalakarans and Boyas; more than half of the Kaikola populations; and the numerous smaller castes, including barbers and washermen, are living in condition of abject squalor and under conditions hardly distinguishable from those prevailing amongst the Scheduled Castes before independence.” (Government of Tamil Nadu 1971: 50-51)

Even after the submission of the A.N. Sattanathan commission’s report, its observation did not effect a policy change with regard to reservation for the backward classes. The DMK, on returning to power in 1989 after a long period of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) rule, sub-classified the reserved seats into backward and most backward classes. This was the result of protests by the Vanniyar caste demanding a bigger share in the reservation quota in education and jobs. Relying on the studies carried out by the Second Backward Classes Commission (December 1982 – February 1985) headed by J.A. Ambasankar, the government carved out 20 per cent of the state’s 50 per cent OBC reservations for 39 communities listed as MBCs.

Surprisingly, the Second Backward Classes Commission report (1980) submitted to the Union government, did not recommend the sub-classification of the OBC category. The Janata Alliance government led by prime minister Morarji Desai set up a commission, commonly known as the Mandal Commission, under the chairmanship of Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal. In his note of dissent, one of the members of the five-member commission, L.R. Naik, disagreed with the idea that castes listed as OBCs are homogenous and recommended sub-classification of the OBC quota. The question that needs to be asked is: After debate and discussion on sub-classification for four decades, why did the Mandal Commission not recommend a sub-quota within the OBC quota? Why wasn’t the sub-classification done when the reservations, as recommended by the commission, were implemented in the early 1990s? Psephologist and activist Yogendra Yadav has written that “the dominant land-owning communities, the driving force behind the pro-Mandal movement, did not allow any sub-quota because it would have hurt them”. Ruling in Indra Sawhney & Ors. v Union of India & Ors. (1992), a nine-judge Supreme Court bench admitted that some castes in the OBCs category are more or less backward than the others. The court allowed the states to sub-classify the OBCs to address such differences. In 2014, soon after the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) came to power, the Union Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment asked the National Commission of Backward Classes (NCBC) to study the possibility of sub-classification of OBCs within the central list. On 2 March 2015, the NCBC, under the chairmanship of Justice (retd) V. Eswaraiah, recommended that OBCs be sub-classified into Extremely Backward Classes, More Backward Classes and Backward Classes. But the recommendation was not accepted.

Under Article 340 of the Constitution, the union government, on 2 October 2017, set up the Commission to Examine Sub-categorisation of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) headed by Justice (retd.) G. Rohini. This four-member commission received thirteen extensions and submitted its report in July 2023, which is yet to be made public. According to an Indian Express article, the Rohini Commission has found that an abysmal percentage of OBC castes have cornered the maximum portion of the reservation quota. The commission finds:

“97% of all jobs and educational seats went to just 25% of all sub-castes classified as OBCs; 24.95% of these jobs and seats went to just 10 OBC communities; 983 OBC communities – or 37% of the total – had zero representation in jobs and educational institutions; and that 994 OBC sub-castes found a total representation of only 2.68% in recruitment and admissions”.

Why caste column in census?

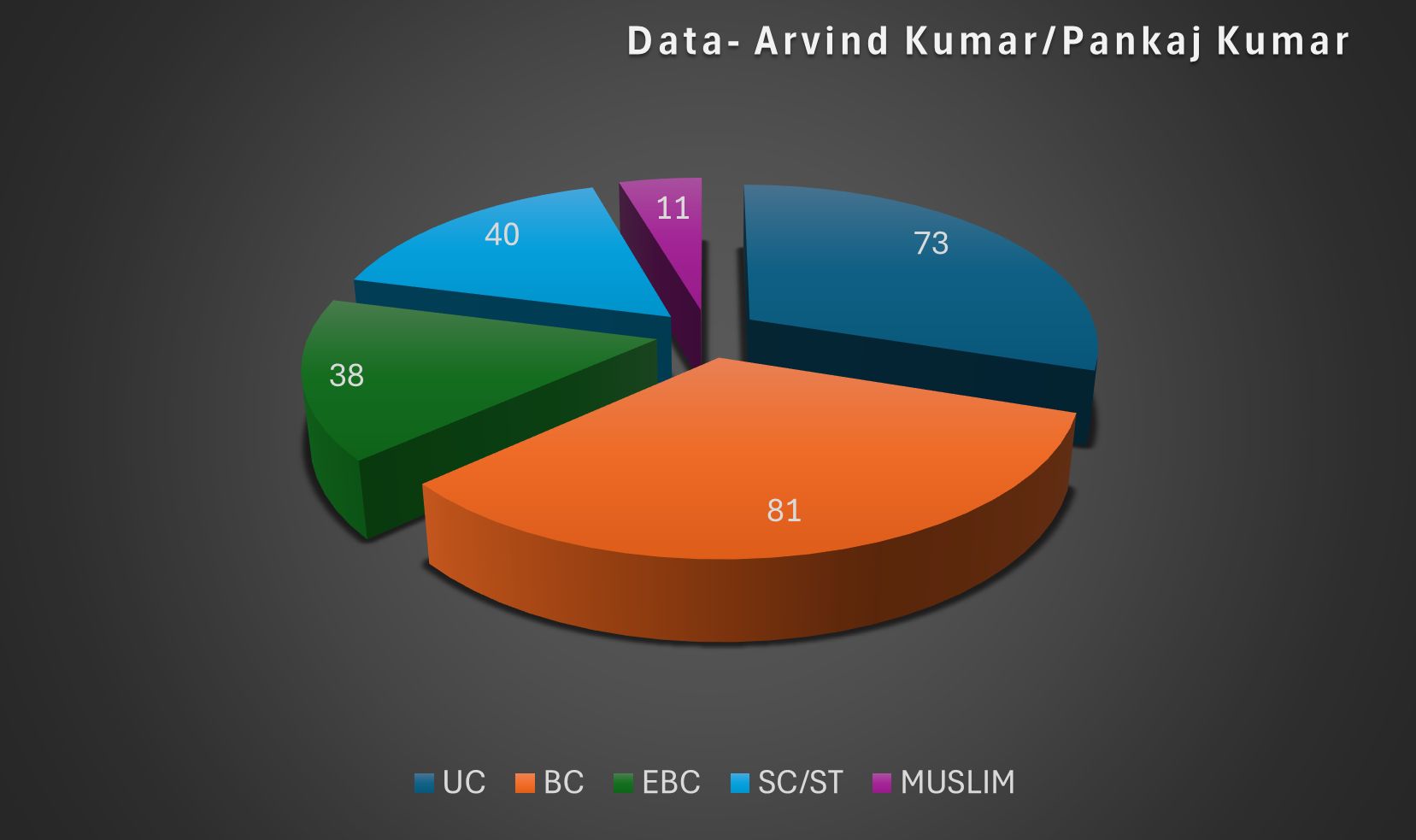

Since the first decennial census of 1871, the British colonial government included caste as a category in the enumeration. Professor (retd.) Anand Teltumbde, in a recent article in Frontline magazine, argued that the colonial government strategically used the census as a potent tool to divide and rule in the aftermath of the revolt of 1857. He wrote that to better know, control and govern India effectively, the British government classified the masses into manageable categories such as caste, religion, tribes and language. The caste enumeration conducted in British India may have contributed to rigidifying caste as an institution in postcolonial India. Then, shall we exclude the caste column from the forthcoming census? Not at all. Our concern should be how the government uses the caste data from the upcoming census. Would the caste data be used to pit castes and communities among the backward classes against each other? Or would it be used to better appreciate historical injustices suffered by sections of society as a result of the caste system, expand the reservation quota for the backward classes and make sure that the most backward castes in the category get proportionate share in higher education and jobs? The Bihar Caste-Based Survey 2022-2023 found that 36 per cent of the population belonged to the Extremely Backward Classes, who have been given merely 12 per cent reservation. The more representative the State is and the more closely it reflects our society, the stronger our democracy will be.

It won’t be enough to divide the 3,700 OBC castes into two categories. Instead, they should be divided into at least four categories. The influential agricultural land-owning castes like Kurmis, Yadavs and Jats in the Hindi belt, the Kunbis in Maharashtra and the Vokkaligas in Karnataka must be placed in one group. The second group should include peasants and allied communities, fish workers and herders with minimal or no land. The third group should comprise artisanal and service communities such as blacksmiths, weavers, carpenters, barbers, washermen, etc. The fourth and last category should include denotified, semi-nomadic and nomadic tribes.

Way forward

It is truly disheartening to see that even after 77 years of independence, we depend on colonial census data to determine representation. If the government genuinely aims at equity, it will not use the planned caste-based census to pit castes against each other for electoral gains but use it for social and structural transformation. A caste-based census, followed by expansion and scientific sub-classification of OBC reservation, can lead to a socio-economic transformation as envisioned by the Constitution.

(Edited by Amrish Herdenia/Anil)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in