The gigantic universe we are a part of is full of mysteries, consisting as it is of innumerable planets, satellites, stars, suns and moons. Earth is one of the planets. There are numerous continents and oceans on the Earth. One of the continents is Asia. This continent has many countries, one of which is India. And Jharkhand is one of the states in India. This state, starting from the time it was created, has been the battlefield of two warring social forces. None of the two is interested in the global power play and the loot of resources. They are unconcerned about a world inching towards another World War. They are least bothered that human rights are being trampled upon and that democracy is increasingly looking like a sham. They – these two groups – are solely focused on one and only one issue – whether Kudmis/Kurmis are Adivasis or not. To find the answer to this weighty question, they are delving into treatises on anthropology. The myriad theories explaining how man appeared on this Earth and what was the trajectory of his development are being dug out and studied diligently. Essentially, the question being probed is who is the original inhabitant of India in general, and of Jharkhand in particular.

The eyes of an eagle flying high in the sky could be transfixed on a small piece of meat lying on the ground. Similarly, this entire exercise, this lofty academic endeavour to search for one’s roots, and the existential questions being asked and answered is actuated by this sole purpose – to get a slice of the pie of the Adivasi reservation quota. The Kudmi community wants itself removed from the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category and added to the Scheduled Tribes (ST) category; they want themselves identified as a tribe, not as a caste. Of course, this is not being said in so many words. What is being said is that Kudmis are Adivasis and that like other Adivasis, they were a part of the Scheduled Tribes. However, during the British rule, they were stripped of their Adivasi status, even though, like the Adivasis they, too, are totemic, that is, they consider different living organisms like fish and tortoises as their ancestors – unlike the Hindus who believe that they were born of sages and saints.

Who and what can stop any particular community from calling itself Adivasi? We all know that anyone can convert to Christianity or Islam. But there is no process of one becoming a Hindu. One is a Hindu by birth. Period. Similarly, there doesn’t appear to be a process of converting to an Adivasi.

One can always adopt the way of life and the conduct of the Hindus to try and look like them. Many foreign tourists enjoy getting married with Hindu rites. Similarly, the Kudmis, who are not considered a member of the Austric group, have been living with Adivasis for centuries and that may have made them adopt the lifestyle and conduct of the Adivasis. That is probably why the two never clashed despite living in the proximity of each other for hundreds of years.

But what we know for certain is that during the Dhankatni movement of the 1970s, two social organizations merged with each other. One was the Adivasi Sudhar Samiti led by Shibu Soren and the other was the Shivaji Samaj, the leader of which was Binod Bihari Mahto, the tallest Kudmi leader to date. Until then, these two social forces, with many commonalities, were mobilized under two different banners. Both these bodies played a key role in the founding of Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM). Kudmis played no lesser role than the Adivasis in the battle against the oppressive moneylenders and for securing a separate state. Many Kudmi leaders, including Shaktinath Mahto and Nirmal Mahto, were martyred in this movement. Then, why did they turn against each other after the formation of the new state?

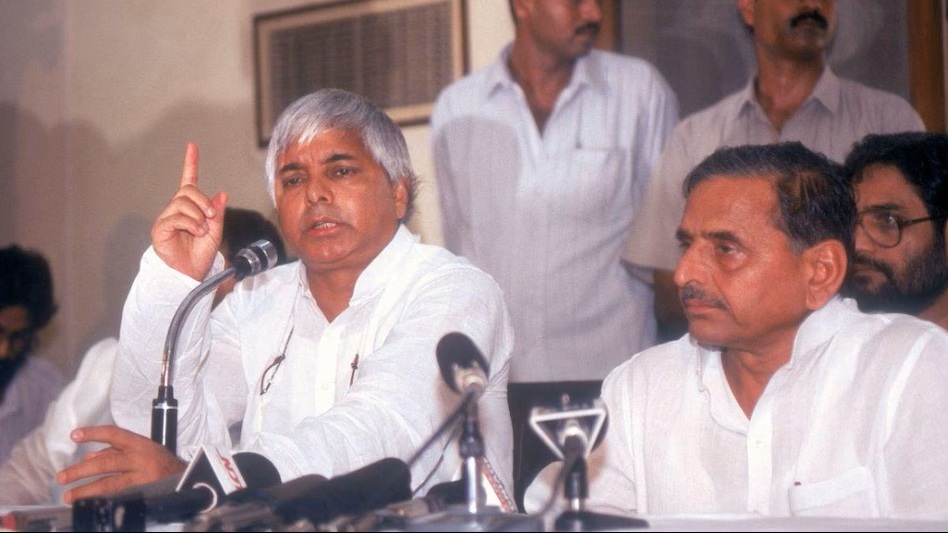

In fact, the tussle on the issue of reservations between the Adivasis and the Kudmis had begun before the new state was carved out from Bihar and it intensified once Jharkhand came into being. This rift was exploited by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) using its Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)-brand politics. Kudmi votes helped the BJP find a toehold in Jharkhand and it continued to wield power in the state till 2019. Though the JMM and others formed their governments for short intervals in between, almost all the chief ministers of the state from 2000 to 2019 came from the BJP.

Before going ahead, let us first try and unravel this knotty issue. Koeris, Kurmis and Jharkhand Kudmis all fall under the Backward Classes or OBC category. Many Jharkhand leaders like Reetlal Verma, Ram Tahal Choudhary and Akluram Mehta came from the Koeri community. In the united Bengal – comprising the present states of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha – the Kurmis were counted among the backward communities. But the Kurmis of Jharkhand, who have been living with the Adivasis for centuries, call themselves Kudmis. However, there was also a time when they had joined a campaign for consolidation of the Kurmi community. A couple of years before Independence, a campaign was launched under the banner of Kurmi Mahasabha to bring all Kurmis on one platform. Kurmis of Bihar, Bengal, Jharkhand and even Maharashtra (where they are called Kunbi) joined this campaign. The objective was to win Kshatriya status and join the club of the upper castes. They started wearing the janeu (sacred thread) and adopted Hindu rituals and customs. The Kurmis all over India are a part of the Hindu Varna system. The bitter truth is that at one time, the Kudmis tried hard to build an identity for themselves distinct from the Adivasis. Amid this, the British removed them from the list of STs – or whatever the category was called then.

Nationally, the reservation for SCs is 15 per cent, for STs is 7.5 per cent and for OBCs is 27 per cent. In united Bihar, the reservation quota for the Adivasis was low. But after Jharkhand came into being, 26 per cent reservation was allocated to the Adivasis and 14 per cent to the OBCs. Moreover, in Jharkhand, the Adivasis have been granted some additional rights under the provisions of the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution and through the PESA Act, which has yet to be implemented fully.

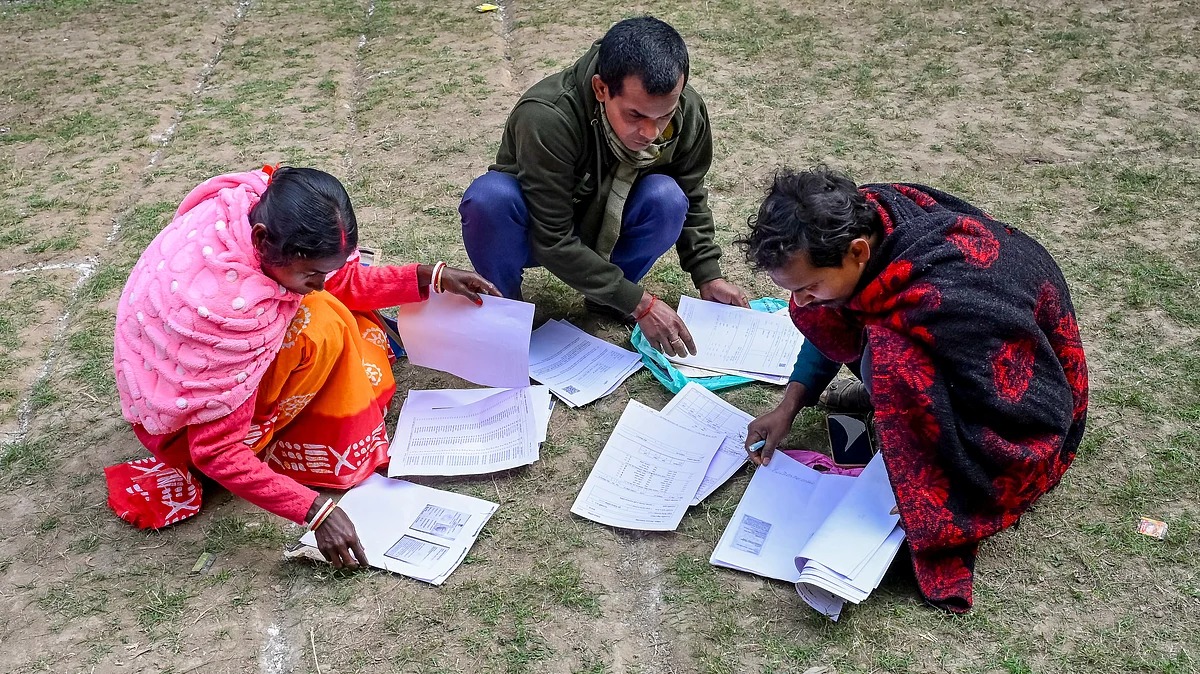

This preferential treatment for Adivasis has distressed the Kudmis. The Kudmis, too, are entitled to reservation but the OBC quota serves a disproportionately large number of potential beneficiaries from the various eligible castes. Just as one prefers to board a less crowded coach in a train, the Kudmis also want to hop on the ST quota, which draws a relatively small crowd. No wonder, it is being loudly proclaimed that the Kudmis of Jharkhand are Adivasis and should be added to the list of STs. They are holding demonstrations, staging sit-ins and have even launched “Rail Roko” (stop train) protests. Some social organizations of the Adivasis are trying to counter them. Recently, a mega demonstration was held in Ranchi. The section of the Adivasis who have benefited from the reservations are active in this counter movement.

The BJP has been caught in a bind. If the Kudmis are accepted as Adivasis, their land, too, will come under the Fifth Schedule. Kudmi votes are a decisive factor in only a few of the 14 Lok Sabha constituencies in Jharkhand. The BJP is unwilling to invite the wrath of the Adivasis from all over the country for the sake of these few seats. The number of seats reserved for the Adivasis in the Parliament as a whole is 47 and more than half of them were won by the BJP in the last polls.

An additional factor is that a movement demanding addition of the Kudmis to the ST list is also underway in neighbouring West Bengal. Kudmi organizations had approached the Calcutta High Court with this demand but it was turned down. In Maharashtra, the Marathas are agitating for OBC (Kunbi) status. Then there is the tension between the Kuki and the Maiteyi communities in Manipur. There, the Maiteyis, who are Hindu, want Adivasi status. The High Court ruled in favour of the demand of the Maiteyi but widespread violence followed in the state.

Be that as it may, currently, the coal belt of Jharkhand, that is, the Dhanbad and Chota Nagpur regions have emerged as the epicentre of the Kudmi movement. That is not without reason. It has a historical context. Acquisition of land in northern Chota Nagpur and the entire coal belt was a smooth affair. Most of the land acquired in Dhanbad, which is now the Bank Mod locality, belonged to the Kudmis. The Kudmis were proud of their status as farmers and were reluctant to work in the coal mines, especially since the wages were low. But after the nationalization of the coal-mining industry, the wages improved substantially. They then felt that they should work in the mines. But by then, outsiders had grabbed most of the jobs. This also happened vis-à-vis the Bokaro Steel project. They allowed the acquisition of their farmland in return for compensation but did not give up their homes and villages. The result was the emergence of two categories of displaced people. The first comprised those who lost both their homes and their farmland and the second, those who lost only their farmland. The displaced persons in the first category got jobs while those in the second category got only compensation. Most of the Kudmis belonged to the second category.

Today, the Kudmi youth don’t have jobs. Cultivable land has shrunk due to the acquisition of land for mining and other activities. That’s why the coal belt has become the epicentre of the Kudmi movement. Hemant Soren and the INDIA alliance, in their manifesto for the assembly polls, had promised changes in the OBC reservation quota. But that promise remains unfulfilled.

That is the reason the Kudmi community are demanding ST status, for increased access to reservation (as STs) would mean increased access to education and jobs. Now, even the Yadavs are arguing that as they graze their cattle in the forests, they are intimately connected with the forests and should be classified as STs. Many other communities also want Adivasi status. At the same time, the Adivasis feel that if the demands of other communities are accepted, they would lose their identity.

It was in this context that the late Dr Ramdayal Munda, a leading intellectual of Jharkhand, told me in an interview, “Yes, we accept that all are Adivasis. Only, we are a bit more Adivasi than the others.”

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in