M.N. Srinivas, one of India’s pioneering sociologists, has described how village settlements reflect the hierarchical order of castes, with upper castes occupying the central locations near temples, wells, main roads and schools and fertile fields while Dalit hamlets stand at the periphery, physically and symbolically separated.

M.N. Srinivas’s classic studies of villages remind us that caste in India was never just an abstract hierarchy, but was directly connected to land ownership and settlement patterns. This spatial arrangement was not accidental. It was how ritual ideas of purity and pollution were implemented and perpetuated. This arrangement did not just passively mirror caste, it actively enforced it.

What M.N. Srinivas observed in the villages, Gautam Bhan unpacks for the city. Bhan shows in his book “In the Public’s Interest”, that Delhi’s “slum” bastis and jhuggi-jhopri colonies are not accidental or chaotic encroachments. They are a planned feature of the urban landscape. Cities like Delhi keep on reproducing these “informal” settlements, pushing working-class migrants, most of them Dalit, OBC and Adivasi, to the city’s edges, where they build fragile homes on urban wasteland. Ironically, these settlements sustain the city’s wealth and keep the city alive. It is the residents of these settlements who build roads and flyovers, offices, commercial spaces, schools and colleges. They sweep the streets and enter sewers to unclog them. They ensure a comfortable life for all but themselves, as their own tin-sheet shacks are “illegal” and can be removed by the government anytime.

Urban legal vandalism: When bulldozing becomes policy

On 11 June 2025, nearly 300 jhuggis were torn down in Govindpuri’s Bhoomiheen Camp (Camp for the Landless), rendering hundreds of families homeless overnight. The party in power today, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), appears to have thrown its predecessor Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) much-touted promise of “Jaha Jhuggi, Waha Makaan”, (an assurance that slum dwellers would get housing where they already live), in the dustbin. People lost not just their tin-roofed homes but their local schools, their jobs, and the fragile networks that helped them navigate the harsh Delhi life.

This is not an isolated incident. Bastis are understood to house as many as 2 to 4 million people, or 15 to 30 percent of the total population of Delhi, but they only occupy 0.5 per cent of the land. Since the 1990s, there have been almost 300 forced evictions in Delhi, usually tied to events like the Commonwealth Games 2010, or “beautification” projects. With the BJP assuming power in Delhi in 2025, demolitions have intensified.

The courts aren’t helping the slum dwellers. In 2020, the Supreme Court ordered the evictions of 48,000 households living on railway lands, revealing in stark terms how disposable the urban poor are. This contradicts Delhi’s rehabilitation policy of 2015, and the verdict in the Sudama Singh case (2010), in which the Delhi High Court ruled that the State must facilitate meaningful resettlement, prior to any eviction.

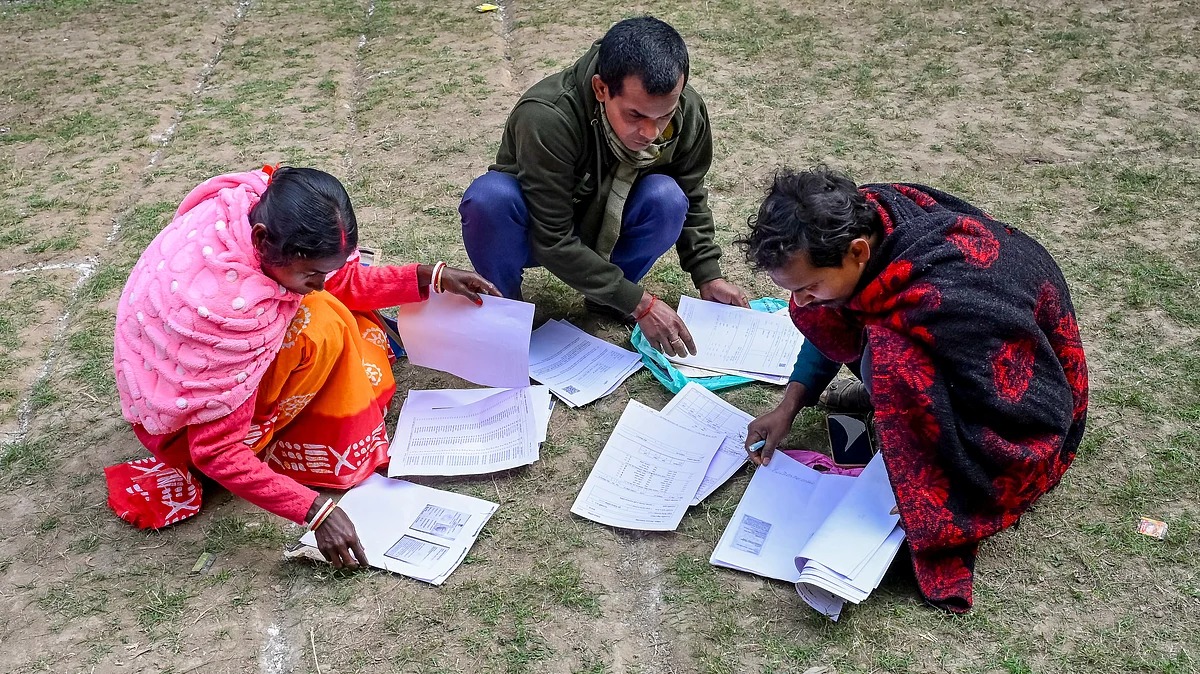

Yet in practice, meaningful resettlement often means a distant promise. Demolitions happen with little or no notice and without comprehensive surveys by agencies like Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB). That means people have to struggle to prove their eligibility for resettlement, despite the humanitarian obligation to protect their basic rights. Instead of planned rehabilitation, families are pushed further to the margins, far from schools, hospitals, or urban job markets. For those who need them the most, the 45,857 unoccupied DDA apartments listed in 2020 might as well not exist. Court judgments state that slum dwellers have a right to housing, along with access to healthcare, education, basic services, and a means of subsistence. But bulldozers often erase that promise in a single afternoon. This is more than a policy failure; it is what some scholars now call urban vandalism – a deliberate destruction of communities in the name of development.

Gautam Bhan: Evictions as urban hegemony

In his book, Gautam Bhan shows how the comforting phrase “public interest” becomes a powerful tool to strip poor settlements of their legitimacy. Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), urban planners and courts disguise their prejudice in the language of “encroachment” and “environmental hazard”, to erase all bastis, as if the people living there are a stain on the city’s pride.

Gautam Bhan explains, case after case, how planners and judges side with the dreams of the neat, gated middle-class colonies, of living in a “world-class” city while riding roughshod over the basic right to shelter of those who build and maintain that same city. Landmark evictions like those in Yamuna Pushta or along the railway lines prove how easily the courts can throw the poor out of their homes even in the middle of a pandemic.

Gautam Bhan shows that the state does not rely on force alone, but operates through a dialectical method of consent and coercion. It produces consent for dispossession through the moral language of “public interest”. Civil society, RWAs, media, government and courts, all manufacture a common consensus that the “world-class city” needs “slum-free” places, metro corridors and smart city zones.

The middle-class sees this as “good governance,” when it actually scatters workers, destroys their collective bargaining power and keeps wages low. The same RWAs that demand evictions depend on these very bastis for supplying them with maids, guards and delivery boys.

“In the Public’s Interest” shifts the focus from what slums are to how cities decide who deserves to stay and who must go. Bhan’s central idea is that “public interest” is not a neutral legal concept but a political strategy that crushes the urban poor through two means.

First, the government and the corporates stamp these settlements as “encroachments”, “illegal”, and “unauthorized”, even though people here often hold ration cards, voter IDs and electricity bills. The same State recognizes them when it wants their votes, but later denies them the right to live there.

Second, their removal is painted as an act done for the greater good. When the State uses the language of environment, development, or public safety to package the evictions, the demolition just doesn’t become necessary, it turns into a moral duty, a lawful step, even a sign of progress. Bhan shows how RWAs, planners and judges together produce this moral vocabulary, acting under the invisible pressure of corporate interests and urban capitalism.

One of Bhan’s sharpest arguments is that evictions are not failures of planning but a method of governance. Evictions are not accidents or mistakes in city planning but a direct reflection of the material reality of urban capitalism and are done to clear valuable land for malls, gated colonies, highways and profitable world-class infrastructure.

This is a method of governing cities by securing capital and real-estate profit. Delhi does not simply fail to provide shelter to its working class, but it governs them through a constant cycle of eviction and resettlement, ensuring cheap labour while freeing prime land for private wealth. The city stays clean for investment, the poor stay expendable and invisible. Bhan’s fieldwork in Delhi shows in painful detail how families living in a settlement for decades can be thrown out overnight with a single court order.

These settlements survive only as long as the land they sit on is worthless to someone richer. The moment a “higher-value” project appears, or a court orders a “clean-up”, entire neighbourhoods vanish. This idea echoes what urban scholar Ananya Roy calls “unmapping”, or the selective erasure of certain people’s right to be mapped as legitimate residents and to make them invisible in legal documents, so that they can be displaced or treated as “illegal” according to the whims of government institutions, which is part of neoliberal urbanism.

The judicial machine

The depth with which Bhan examines the function of the courts is one of the unique features of his work. He follows historic cases, such as the demolitions of the Yamuna Pushta, in which the Delhi High Court ruled that thousands of shanties were unlawful and ordered their removal to protect the river. However, he notes that an upscale residential project, a thermal power plant, and a metro depot on the same riverbank remained untouched. Why? Because the term ‘encroachment’ is used selectively – some encroachments are in the “public interest”, while others are “illegal”. Through middle-class housing associations’ PILs to “protect the environment” which actually end up erasing the urban poor’s histories of labour and survival, Bhan shows how the judiciary is not impartial and actively pushes the idea of a “clean city”.

An important contradiction Bhan highlights is that the city needs the people it displaces. They are forced to live in tin-roofed bastis and makeshift settlements because the city never bothered to plan affordable housing for them. Bhan’s analysis concurs with Ambedkar’s observation that economic oppression and social exclusion are mutually reinforcing. While the city requires flexible, low-waged labour, it never wants that labour to live next to it.

Dr Ambedkar: Untouchability as spatial order

Dr Ambedkar, writing on untouchability, showed that it is not just ritual exclusion but a form of social slavery tied to space. Dalit settlements were historically pushed to the edges of villages, cut off from water sources, temples and communal spaces. The logic was clear – separation, which sustains caste hierarchy through the idea of pollution. Dr Ambedkar observed that Dalit workers in colonial India were treated as cheap, flexible labourers and kept in impoverished, neglected areas of industrial cities. This is the case even today when governments drive bastis to the outskirts of cities while continuing to exploit the labour of their residents. Dr Ambedkar also expressed concern that if the State defends dominant interests, it may end up being the biggest violator of human rights. He argued that without safeguards, the State becomes an agent of the upper classes, bulldozing settlements under the pretext of “beautification” or “public interest”.

When the State demolishes bastis along riverbanks, flyovers, or on so-called “prime land” for “public projects”, it repeats the same grammar: removal, distancing and invisibilization. While observing these problems our privilege makes us caste-blind. But the “encroacher” label becomes the new untouchable status, justified through urban planning discourse rather than religious purity.

These facts prove that caste does not just mark “pollution”, it is also a determiner of the terms of labour.

If we read Bhan carefully alongside Ambedkar, we see how caste and class exploitation are inseparable. Ambedkar warned that mere industrialization would not erase caste. Instead, caste would become capitalism’s local manager for cheap labour.

Bhan shows that Dalit and OBC migrants do not escape caste when they move to cities – they are recorded as “encroachers”, “unauthorized”, “illegal occupants”, which are the new words for untouchability in the urban context.

The present: A city that continues to define boundaries

The year 2024-25 saw more demolition notices from the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) and the railways than ever before. Because courts continue to prioritize the “public interest” of the upper classes over the interests of those living in these settlements, legal services frequently fall short of protecting the poor. In Gramscian terms, the state’s assertion that it is acting in the “public interest” functions as hegemonic common sense, first normalizing the eviction of working-class communities and then obscuring the identity and interests of the urban elite. For instance, families of Delhi’s traditional puppeteers and performers used to reside in the Kathputli Colony, which was demolished. Many of the lower-caste artisan communities were dispossessed for a redevelopment project described in the notice as urban beautification.

Continuities: Rural logic in urban form

What connects Srinivas, Ambedkar and Bhan is this insight: caste does not vanish with migration or urbanization. The same factors that drive Dalit hamlets to the outskirts of villages also drive bastis to the outskirts of cities, where they must remain invisible while providing services to those who are visible.

This continuity reminds us that “urban” problems are no different from “rural” ones but extensions of them.

Conclusion: Reimagining the city

Dr Ambedkar warned us that so long as caste endures, so will untouchability even if it changes form. Bhan’s work shows us how planning, laws and courts produce new versions of that untouchability under the cover of “public good”. Srinivas reminds us how staunchly these boundaries are adhered to in everyday life.

To protect Delhi’s working poor from fresh waves of demolition, we must ask, whose public interest does the city serve? Why are the right to housing, dignity, and neighborhood memory not seen as public interest? Why do we plan cities that hide the working poor rather than cities that accept and honour their centrality?

Bhan’s argument is that eviction is not a “planning error”. It is a consequence of the political economy and material reality. Fighting eviction means fighting a political and economic structure that uses caste to scatter the urban poor, keeps them insecure and disposable, as global capital goes around seeking land.

The only solution is what Dr Ambedkar demanded for the village: land, secure tenure, and collective rights. In the city, this means legal housing rights for working-class settlements, decommodification of land and extensive public housing in the city proper.

References

- Gautam Bhan, In the Public’s Interest: Evictions, Citizenship and Inequality in Contemporary Delhi, University of Georgia Press, 2016.

- M.N Srinivas, Religion and Society among the Coorgs of South India. Oxford University Press, 1952.

- B.R. Ambedkar, Annihilation of Caste, 1936.

- B.R. Ambedkar, The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables, 1948.

- B.R. Ambedkar, What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables,1945.

- B.R. Ambedkar, States and Minorities, 1947.

- Ananya Roy, Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning, 2005

(Editing: Anil/Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)