Dalit Studies has carved out a decisive place in South Asian social sciences, both inheriting and breaking away from the Subaltern Studies project. Subaltern Studies, launched in the 1980s under Ranajit Guha, sought to rewrite Indian history from below, foregrounding peasants, Adivasis and labourers against the grain of elite narratives. But while it challenged class and colonial hierarchies, it often left caste on the margins. Dalit Studies marks a critical departure. By placing caste, dignity, and untouchability at the centre, it shifts the axis of inquiry from a broad subalternity to Dalit subjectivity itself, making the struggle for recognition and equality the very core of India’s democratic imagination.

Between 1982 and 2005, the twelve volumes of Subaltern Studies reshaped South Asian historiography, recasting marginalized groups as agents of resistance rather than mere subjects of elite politics. The early volumes, inspired by Gramsci, centred on peasant insurgency, while later ones drifted toward cultural and postcolonial theory. By the 1990s, however, the limits of the project were clear – a narrow preoccupation with agrarian revolts, a neglect of caste and gender, and an increasing textualism that dulled its radical edge. Marxists faulted it for romanticizing insurgency, while feminist and Dalit scholars exposed its silences on patriarchy, untouchability and caste oppression – validating Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s provocation about whether the subaltern could truly speak.

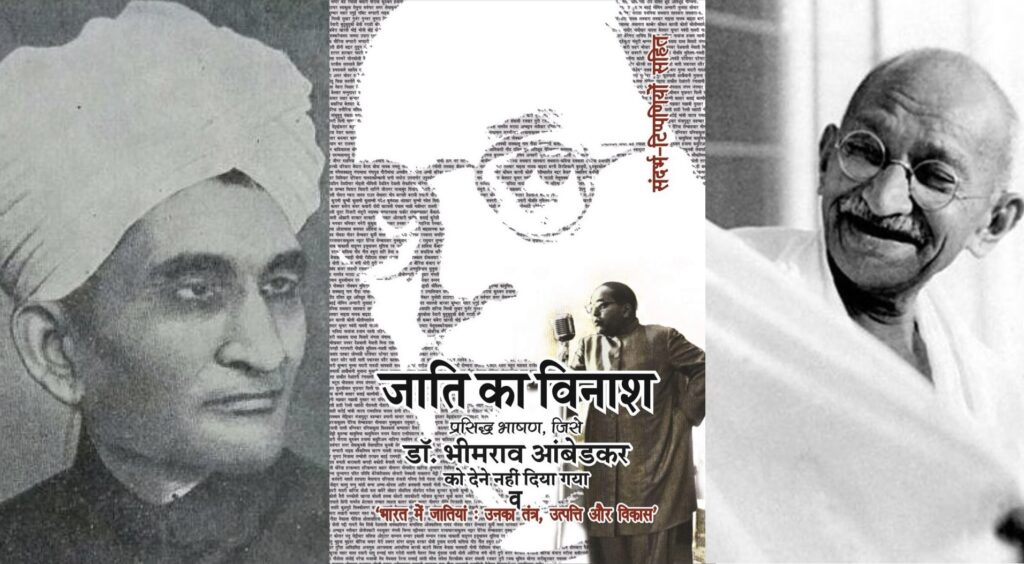

The 1990s, marked by the Mandal debates, anti-reservation agitations, Dalit literature and feminist assertion, also witnessed the rise of Dalit Studies. If Subaltern Studies centred class and peasant insurgency, Dalit Studies placed caste at the core. Drawing on Ambedkar rather than Gramsci, it privileged autobiographies, oral histories and life narratives over colonial archives. Its focus was not descriptive but normative and activist, dedicated to dismantling caste oppression and affirming dignity. More than a thematic shift, it was a methodological milestone – a democratization of knowledge where Dalit voices, long spoken for, now spoke for themselves.

With Dalit Studies, the authority of elite academics gave way to Dalit intellectuals, writers and activists shaping the field. It can be seen as both a continuation and a radical transformation of the subaltern project. Placed within a new historicist frame, Dalit Studies also collapses the line between text and context, treating autobiographies, poems, oral testimonies and everyday practices as historical documents. Like New Historicism, it turns to unconventional archives and explores the interplay of power and resistance. However, it moves beyond description. Anchored in Ambedkar, Phule, the Dalit Panthers, and Black radical thought, Dalit Studies is explicitly activist, centred on dignity, equality, and emancipation. It combines method with political purpose, making self-representation its core.

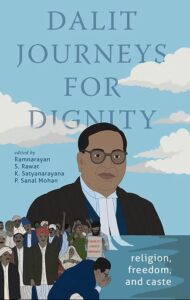

It is against this backdrop that the two volumes of Dalit Studies must be read. The first volume (2016) established the field, historicizing Dalit politics and thought while probing questions of representation and reservations, feminism, and identity. But it is the second volume, Dalit Journeys for Dignity: Religion, Freedom, and Caste (2025), that crystallizes the intellectual direction of the project. Edited by Ramnarayan S. Rawat, K. Satyanarayana and P. Sanal Mohan, it grew out of the International Dalit Studies Conference on “Human Dignity, Equality and Democracy” held in 2018. Its central theme is dignity, which the editors trace through Ambedkar’s concepts of the “social” and “moral stamina”.

In their introductory essay, Rawat and Satyanarayana set the conceptual foundation for the volume, stressing that the Dalit struggle was never about survival or material improvement alone. It has always been an exhortation for self-respect and a demand for recognition as human beings, and above all, for dignity. By framing Dalit history in this way, they shift the debate from poverty and redistribution to the terrain of ethical and social existence. Central here is Ambedkar’s distinction between the “social” and the “political”. Colonial and nationalist politics, Ambedkar argued, centred on constitution, elections and self-rule, but ignored the everyday realities of caste humiliation. As Ambedkar argued, political democracy is unsustainable without a foundation of social democracy – a society based on equality, fraternity and justice. This insight becomes the intellectual framework of the entire volume. Each essay builds on it in different ways, showing that struggles over religion, property, sexuality or dress are fundamentally struggles over the social, and that democracy without dignity is merely an empty slogan.

Equally important is Ambedkar’s idea of fraternity and its direct link to dignity. His insistence on the phrase “fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual” in the Constitution’s Preamble was no ornament. For him, liberty and equality were incomplete without a community of mutual recognition. The editors also highlight Ambedkar’s concept of moral stamina – the inner strength to endure humiliation and sustain long struggles against entrenched hierarchies. For Dalits, facing repression, betrayal and caste hostility, this stamina was crucial. Dignity here is not borrowed from Western human rights but rooted in Dalit histories of pain, resistance and refusal.

The essays that follow bring this understanding to life in diverse ways. Chakali Chandra Sekhar narrates the story of Nanchari, a Dalit from Andhra Pradesh in the 1830s, who defied temple entry bans, endured beatings, refused caste labour, and embraced Christianity as resistance. His conversion was not escape but defiance, a weapon against caste. His example sparked mass conversions and collective assertion. Sekhar reads his life as embodying Ambedkar’s themes: dignity as refusal, conversion as emancipation, and social stamina as survival.

Ramnarayan Rawat links Ambedkar’s vision of fraternity with Kabir and Ravidas. He shows how Dalit politics was never only about redistribution but about transforming the very fabric of community into one bound by equality and recognition. Everyday practices – literary circles, cultural gatherings, unions – became sites where dignity was lived, not just demanded. Lucinda Ramberg tries to see how caste and sexuality are inseparable. Caste reproduces itself through endogamy, by policing women’s bodies and regulating intimacy. For Ambedkar, annihilation of caste meant annihilation of enforced endogamy. For Ramberg, Dalit futures cannot be imagined without dismantling this sexual order. Inter-caste marriages, struggles against moral policing, and the assertion of Dalit women’s sexual agency become central to the politics of dignity. Here we see how Dalit Studies forces social sciences to engage with the intimate, with the everyday as the site of structural reproduction.

Koonal Duggal traces the emergence of Ravidassia religion in Punjab. After the 2009 assassination of Sant Ramanand, Dalit assertion was criminalized as blasphemy, but the community reframed it as martyrdom, laying the foundation of a new religious identity. The creation of the Amritbani and the declaration of Ravidassia religion indicated how dignity and religion intertwine. Martyrdom becomes a political grammar through which violence is converted into authority. Jestin T. Varghese examines Dalit Christianity in Kerala. Missions opened schools and promoted literacy, but also reproduced segregation. Dalits were baptised yet denied burial rights, leadership, or equality in church life. Out of these contradictions emerged a distinct Dalit Christian faith community, reinterpreting Christianity through their own experience. This was not a gift of missionaries but a result of Dalit refusal to accept humiliation, forging an autonomous ethical community.

Anupama’s analysis on sartorial dignity reminds us that even clothes are political. Ambedkar urged Dalit women to invest in good clothes for self-respect. Dalit communities contested the visual regime of caste by adopting Western dress, silver ornaments, or clean uniforms, signalling dignity and mobility. Sartorial choices became practical ethics, reworking the visual codes of caste. Sharika Thiranagama turns to Kerala to examine how inheritance and kinship reproduce caste hierarchies. Despite land reforms and literacy, Dalits remain excluded from property transmission. Inheritance, she argues, is a hidden but powerful mechanism of caste continuity. By highlighting these structures, she critiques Kerala’s self-image as a progressive state and insists that dignity requires dismantling inherited inequalities.

Sumeet Mhaskar explores caste in modern industry. Factories may appear caste-neutral, but recruitment and workplace networks reproduce hierarchies. Dalits are overrepresented in hazardous, insecure jobs and excluded from supervisory roles. Modern industry, he argues, offers “immobility within mobility” – better wages perhaps, but without real dignity or equality. Finally, Dickens Leonard reconstructs Tamil intellectual Iyothee Thass’s “anti-caste hermeneutic”. Thass reinterpreted Tamil history to assert that Dalits were historically linked to early Buddhism, reclaiming a spiritual lineage that predated and resisted Brahminical orthodoxy. By reclaiming Buddhism, he offered Dalits not just a new faith but a genealogy of dignity. His work prefigured Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism and illustrates how reinterpreting history becomes a weapon of emancipation.

Taken together, these essays do not merely provide case studies. They create a conceptual map of dignity as the thread running through religion, occupation, sexuality, kinship, industry and culture. They show how Ambedkar’s concepts of the “social” and “moral stamina” are lived in practice. They push the social sciences to confront caste not as a residue of tradition but as a structuring principle of modernity.

These studies mark a turn in the social sciences and they democratize knowledge by spotlighting Dalit voices. They expand the archive by drawing on oral histories, autobiographies, sartorial practices and religious innovations. They force interdisciplinarity, bringing history, sociology, anthropology, political science and literary studies into dialogue. And they insist that scholarship is not neutral but part of the struggle for dignity. Dalit Journeys for Dignity stands as confirmation of that insistence, reminding us that the struggle for dignity is not over, but remains central to Indian democracy.