Alarmed by the growing Hindu extremism and communalism, and the open attack on Constitutional rights of religious minorities, Indian secularists and liberals are invoking Gandhi, Nehru, Ambedkar and – in the more leftist circles – Bhagat Singh. These figures from modern Indian history are being put forward as symbols of religious tolerance, non-violence, Dalit empowerment and even socialist revolution.

Few, however, have remembered E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker, better known as “Periyar”, the founder of the Dravidian movement in southern India. As I will argue, without understanding Periyar’s philosophy, actions and methods of mobilization, it is not possible to challenge the idea of Hindutva, and the forces of obscurantism, communalism and upper-caste hegemony it represents.

Undoubtedly Periyar’s greatest contribution was that of thoroughly exposing varnashram dharma, the Hindu caste system, which confers superior or inferior status to people by birth and not by individual merit. Though he was certainly not the first to point this out, Periyar was the most forceful critic of Hinduism’s arbitrary division of society into the “high” and the “low”.

Undoubtedly Periyar’s greatest contribution was that of thoroughly exposing varnashram dharma, the Hindu caste system, which confers superior or inferior status to people by birth and not by individual merit. Though he was certainly not the first to point this out, Periyar was the most forceful critic of Hinduism’s arbitrary division of society into the “high” and the “low”.

“One should respect others in a way in which one expects to be respected by others. This is a revolutionary principle for the Hindus. It can materialize not by reform but by revolution only. There are certain things that cannot be mended, but only ended. Brahmanic Hinduism is one such thing,” Periyar said.

The politics, administration and education system of Tamil Nadu at the beginning of the 20th century, like many other parts of India, was overwhelmingly dominated by Brahmins. For instance, although the Brahmins were only 3.2 per cent of the population, 70 per cent of the university graduates between 1870 and 1900 were Brahmins. In 1912, Brahmins formed 55 per cent of the deputy collectors, 82.3 percent of sub-judges and 72.6 percent of munsifs. In contrast, the respective shares of non-Brahmins, despite their much larger numbers, were 2.5, 16.7 and 19.5 per cent only. Such domination was possible because, apart from their traditional social advantages in the pre-British period, Brahmins in Tamil Nadu took to English education in larger numbers and with greater ease and motivation than other castes. Periyar joined hands with other political groups challenging Brahmin hegemony to demand proportional reservation for non-Brahmins in all government jobs and educational institutions. Despite strong opposition from the Brahmin lobby, Madras state, the precursor to Tamil Nadu, was the first state to implement such reservations in 1928.

Later on, in 1950, when the Supreme Court held that such reservations were unconstitutional, the resulting agitation in Tamil Nadu forced Jawaharlal Nehru’s government at the Centre to bring in the first constitutional amendment to uphold the right of the government to enact laws that provide for “special consideration” for weaker sections of society, such as the reservation policy.

Along with levelling the playing field for non-Brahmins in employment and education, Periyar sought to deconstruct the theoretical basis of the caste system, which claimed legitimacy from the Vedas and Hindu scriptures like the Puranas or epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharata. Periyar and other scholars of the Dravidian Kazhagam (DK), which he founded, laid bare the contradictions, biases and immorality of these religious texts in great detail and showed how they provided religious sanction to the caste system.

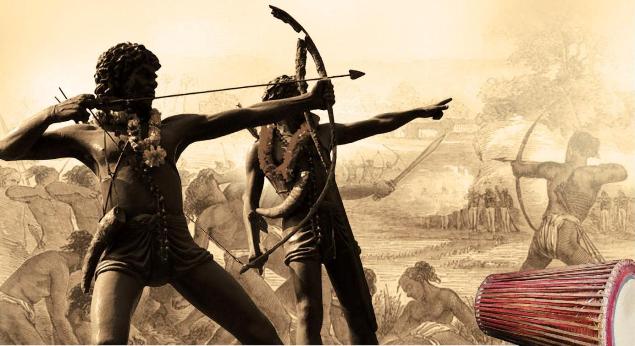

For example, the Dravidian movement offered a detailed critique of the Ramayana, which, according to Periyar, was essentially a tale of conquest of the indigenous people of India – broadly categorized as Dravidians – by migrant Aryans, coming from central Asia. The Brahmins of Tamil Nadu had used Max Muller’s concept of the culturally “superior Aryan” to legitimize their authority and the Dravidian movement opposed this concept as the point of departure in its politics.

Ravana as the hero

In their reading of the Ramayana, the hero of the epic Rama is actually the invading villain and Ravana, the so-called “demon king”, is the victim of Rama’s aggression. The book Ravana Kavyam, a Tamil epic written in the early period of the Dravidian movement, extols the virtues of Ravana, while DK activist and film personality M. R. Radha’s theatrically provocative parody on the Ramayana depicts Ravana as a great hero. In numerous public meetings, Dravidian activists burnt copies of the Ramayana for its portrayal of Dravidians as “rakshasas” or, at best, as monkeys and bears who were allied to Rama.

“Invocation of Ravana functioned as an antidote, restoring the pride of the Tamils in the non-sanskritic regional culture and unleashing a critique of Brahmanism. If Indian nationalism uncritically prided itself as Aryan, Ravana was the response from the alienated south”, wrote M.S.S. Pandian, the late scholar of the Dravidian movement.

Periyar opposed blind faith in religion and superstitious practices by promoting rationalist thinking based on the study and understanding of modern science. In particular, he attacked the phenomenal waste of hard-earned money and resources of ordinary people on meaningless rituals and donations to temples that ended up enriching only the Hindu upper caste.

Despite his opposition to religion in general, Periyar asserted the right of non-Brahmins to enter the sanctum sanctorum of Hindu temples, arguing that stopping them from doing so was to deny them status of human beings. In 1970, Tamil Nadu again became the first state in India to have a legislation brought in – by the newly elected Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government of C.N. Annadurai – to ensure that people from all castes could become temple priests.

One of the key reasons for the success of the Dravidian movement was its brilliant, legendary use of language and culture to awaken people, with many of its leaders being not just skilled orators but also good poets, musicians, actors and writers. Opposing the imposition of Hindi on southern states by the Indian government was a natural corollary to the Dravidian movement’s arousal of pride in the Tamil language and culture, with Periyar even threatening to fight for a separate “Dravidanadu” in response.

It was the mobilization of support around this issue that propelled the DMK, a breakaway group from Periyar’s own Dravida Kazhagam (DK), to power in Tamil Nadu in the 1967 elections. The spectre of separatism, along with the fierce anti-Hindi agitation, compelled the Indian government to take the demands of the Dravidian movement seriously enough to offer many concessions to the state on the economic and political fronts.

On the social front, to reduce the role of Brahmins in the daily life of ordinary people, Periyar promoted what he called “self-respect marriages”, which enabled couples from any religion to get married in a secular manner through just a simple exchange of garlands and without the services of any priest. These marriages were legalized through a special act brought in by the DMK government in 1967.

Periyar’s feminism

Periyar’s most revolutionary insights were perhaps in his espousal of radical feminism, which he theorized well before the term itself was invented anywhere in the world. Periyar, for example, attacked the oppressive notion of female “chastity” thus: “To insist that chastity is only for women and should not be insisted upon for men, is a philosophy based on individual ownership; the view that women are the property of the male determines the current status of a wife.”

Periyar’s championing of the right of women to get educated, work and live and love as they please was too bold for many of his own ardent followers in the DK movement, which has failed to elaborate or even uphold his thoughts on this issue.  As the feminist and Periyar scholar V. Geetha pointed out in a recent talk in memory of the 19th-century social reformer Savitribai Phule, “Periyar has been de-radicalized and made an exponent of the reservation policy, crude atheism and a strident anti-Brahmin rhetoric, and so his views on caste, hierarchy, the gender and sexuality question have all been relegated to a forgotten archive.”

As the feminist and Periyar scholar V. Geetha pointed out in a recent talk in memory of the 19th-century social reformer Savitribai Phule, “Periyar has been de-radicalized and made an exponent of the reservation policy, crude atheism and a strident anti-Brahmin rhetoric, and so his views on caste, hierarchy, the gender and sexuality question have all been relegated to a forgotten archive.”

Indeed, much water has flowed in the Kaveri since the heyday of Periyar, and the political parties born of the Dravidian movement have decayed to a point where they have compromised on many of other issues too. Today, Tamil Nadu’s ruling politicians have become notorious for rampant corruption, casteism, patriarchal attitudes and, in more recent times, even forming alliances with the BJP, once the hated promoter of “Aryan supremacy” and Hindi chauvinism.

The state has also courted infamy in recent years for attacks on Dalits by the middle castes who, while benefiting from the anti-Brahmin movement, do not want those below them to assert their own rights. This was something Periyar had warned about when he said that as long as there was a hierarchy of castes in Hindu society there could always be conflict between those on different rungs of the ladder.

Despite the subsequent distortion of Periyar’s legacy in all these different ways, it can be said that the Dravidian movement effected the most successful social transformation in modern Indian history on the issues of caste, education, assertion of language and gender rights. Tamil Nadu, thanks to Periyar, is one state where the Brahmins no longer dominate politics and society or set the standard for cultural “superiority” in any way.

The assertion of pride in the Tamil language has resulted in widespread literacy in the mother tongue while the socialist leanings of the Dravidian movement have helped the state develop the best primary healthcare infrastructure in the country today. Tamil Nadu also has the lowest occurrence of communal disturbances, with the Hindutva forces finding it extremely hard to grow here, despite many desperate attempts to do so.

All these achievements were made through a largely non-violent movement drawing strength from well-researched arguments, creative communication techniques and popular mobilization. The Dravidian movement offers an excellent model to the rest of India to combat the barbarism of the caste system and establish a society where reason and democracy prevail over the dictatorial urges of a tiny minority of upper-caste Hindus.

One area, though, where the Dravidian movement’s legacy needs to be complemented is class issues. While Periyar became a great fan of the Soviet Union after a visit there in the 1930s and was a proponent of socialist principles he did focus a bit too much on caste at the expense of differences in wealth and income in society.

At this juncture, when an unholy alliance of global and domestic capitalists and traditional religious elites is leading the country towards majoritarian fascism, it is only the united front of caste and class assertion that can offer a fitting response.

‘Socrates of South Asia’

Born in 1879 into a rich family of traders in Tamil Nadu’s Erode district, Periyar was a pious young man, greatly influenced by his father’s inclination towards Vaishnavism. However, during a trip to Varanasi in 1904, the crude discrimination against non-Brahmins he experienced personally turned him into an atheist and a fierce critic of the Hindu caste system and what he called the subjugation of the so-called shudras by the Brahmins.

Despite this, his growing popularity as a social reformer in Erode led the Congress stalwart C. Rajagopalachari, a Brahmin, to befriend him and invite him to join the Congress in 1919. Periyar joined the party and became an ardent Gandhian, making numerous personal sacrifices during the non-cooperation, anti-liquor and swadeshi movements. He went on to become the president of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee but failed to get his own party’s support on issues such as the right of non-Brahmins to enter temples or for the creation of trusts to manage religious institutions. In 1925, he finally quit the party in disgust after failing repeatedly to get its support for a policy of reservation for non-Brahmins in government jobs and educational institutions.

Periyar then joined the Justice Party, a political formation that was championing the cause of the backward castes, and challenged the overwhelming Brahmin domination of everything from politics and administration to education and culture in Tamil Nadu. In 1944, the Justice Party was renamed the Dravida Kazhagam (DK).

Periyar breathed his last on 24 December 1973 at the ripe old age of 94. A few years earlier, in 1970, he was honoured by UNESCO with an award, the citation of which said: “Periyar, the Prophet of a New Age, Socrates of South Asia, Father of the Social Reform Movement, Arch Enemy of ignorance, superstitions, meaningless customs and base manners.”

Published in the June 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine