Anger and rebellion against the establishment had been simmering in the hearts of the Dalits and Tribals of Nepal for the last many centuries. Whenever it broke out into the open, the Hindu imperialists managed to douse it. They did everything possible to stop them from dreaming. But in spite of their efforts, the dreams were being passed on from one generation to the next. Whether it be in Nepal or India, Dalits and Tribals have been deprived of their forests, land and water. The Savarnas mortgaged their lives and extracted from them whatever work they wanted. They played with the honour of the women of these communities. The outcome of the struggle waged by the politically conscious members of the Dalit, Tribal and Backward classes, braving innumerable odds is before us. The centuries-old Hindu Rashtra of Nepal has been razed to the ground and a Constitution based on equality, liberty and brotherhood has come into force. The historic achievement comes after a seven-year-long political struggle and tug of war. The new Constitution came into force in the second fortnight of September, amid violent opposition by the Manuvadis. Nepal has now been freed from the Hindu yoke and has become a secular, democratic republic.

President Rambaran Yadav told the Constituent Assembly, “I announce the presented Constitution of Nepal, passed by the Constituent Assembly and authenticated by the chairman of the Constituent Assembly, effective from today, 20 September 2015”. The Constitution provides for reservations to empower Dalit, backward and regional communities, and women.

President Rambaran Yadav told the Constituent Assembly, “I announce the presented Constitution of Nepal, passed by the Constituent Assembly and authenticated by the chairman of the Constituent Assembly, effective from today, 20 September 2015”. The Constitution provides for reservations to empower Dalit, backward and regional communities, and women.

Nepal’s evolution as a Hindu Rashtra has a long history. In 1768, when the king of Gorkha unified Nepal, he designated only Nepali as the national language of the country, ignoring languages of all other nationalities. It became its official language, too. The only other language that got official recognition was Sanskrit. This was never accepted by the other nationalities. But despite this, Nepali continued to enjoy pre-eminence in the country, with Sanskrit and English supplementing it. Nepali was the language of the Gorkha kingdom. That is why, the “Nepalis” are also known as “Gorkhalis”. One of the Maoist guerrilla fighters said, “Economic hardship was not the only reason why I joined the people’s war. It was also because I come from an indigenous ethnic group. Here, we could neither study in our mother tongue nor converse in it. We were forced to endure the oppressive Hindu government of the Centre. We wanted to change all this through a revolution. How much we have succeeded in our endeavour is for others to judge. But the objective of our struggle was to bring about social change.”

There are around 25 oppressed tribes in Nepal. The main ones among them are Magar, Newar, Bhotia, Tamang, Limbu, Rai, Sherpa, Gurung, Sunuwar, Kirat and Lepcha. They all have their own languages. Newari, the language of the Newar tribe, even has its own grammar and written literature. Its dictionary is also available. But due to political reasons, this language was ignored. The Newaris have their own organization called Newar Khala. Its president, Dileep Maharjan, says, “Aryan and Hindu religions were considered superior and the government patronized them. The Nepalese language rules in offices, schools and other places. Newaris were forced to study Nepali. They were not allowed to learn their own language. Most of the Newaris are Buddhists. But Nepal was a Hindu Rashtra. Here Hindu religion, Nepalese language and Aryan culture were accorded the highest status. Newaris are the indigenous people of the [Kathmandu] valley. They neither got jobs nor were they recruited in army and police. They also could not enter politics.”

Western Nepal is dominated by the Magar tribe. This community has been demanding that their children be taught in their own languages – Kham, Magar and Kaykek. But the government did not allow it. Most of the Magars speak both Nepali and their own language. The government teaches Sanskrit in schools. Demonstrations were staged against Sanskrit and Sanskrit books were burnt. But the government was unmoved.

A Hindu Rashtra was considered the ideal by the elite of Nepal as well as the Hinduvadi political parties of India. Any talk of its imminent fall made them lose their night’s sleep. However, they should have remembered that the monarchy of Nepal was never pro-people.

Members of four major political parties – Nepali Congress, CPN-UML, UCPN (Maoist) and Madhesi Jana-Adhikar Forum (Democratic) – together constituted 90 per cent of the 601-member Constituent Assembly. A majority of the members of the assembly were protagonists of the Hindu Rashtra. The Dalits and the minorities were given only token representation.

Vishwendra Paswan, a fighter for Dalit rights, was included in both the Constituent Assemblies. He started his movement in Nepal in 1972-73. He founded the Bahujan Shakti Party. He led several demonstrations on Dalits issues, including reservations for them in educational institutions and in government jobs. But most of the members of the assembly disagreed with him.

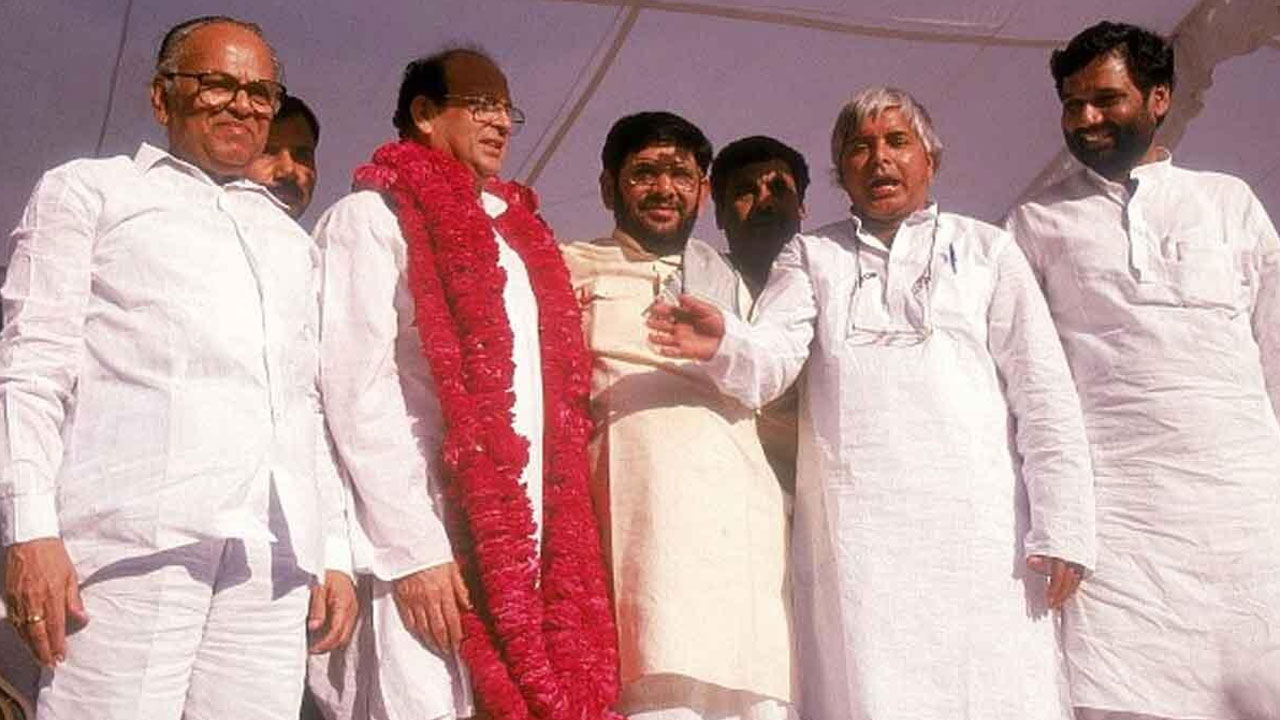

Paswan was in Delhi recently. As their first international initiative, Indian Dalit writers and social activists launched a movement against plans to keep Nepal’s Hindu Rashtra tag intact. And their efforts bore fruit. It was due to Paswan’s strenuous efforts that the movement was launched. Over the last two years, he visited Patna, Lucknow, Haryana and Delhi on numerous occasions. He built contacts with the Bahujans of India. Many Dalit activists individually and on behalf of their organizations submitted memoranda to the Embassy of Nepal in India. The saga of Paswan’s struggle in Nepal has become part of history. It is time to raise a new slogan: Bahujans of the world, unite.