I don’t claim to know much about Ambedkar, apart from a few of his essays I have read and audio clips I have heard. But I know Ambedkarism. I have seen Ambedkarism in practice much more than I have in theory. Hence, I will be talking here about the “context” of Ambedkarism rather than the “text”.

My engagement with Ambedkarism dates back to my time in the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, where I was studying for the Master of Arts in Social Work (MSW). It was sometime in early 2011 that some of my peers asked me to join them in “Ambedkarite” programmes like film screenings, lectures, discussions, reading sessions, etc. In the classroom, we were taught that the important features of a social worker is carefully observing, sincerely listening and effectively communicating. I listened to stories of caste-related discrimination and violence both during classroom lectures and elsewhere.

Ambedkarism stands out

What made Ambedkarism special to me? After all, we were introduced to many thinkers and many -isms like Marxism, feminism, and post-structuralism. Ambedkarism’s real passion for social change and development appealed to me. Dalits, as they used to identify themselves, had a lot of enthusiasm to improve the world they were part of. I was never made to feel that I was an outsider by those students. Identities which are extremely close to us, are mostly hidden in the public space. Mostly Brahmins and other savarnas use their identities in public with confidence. People not that privileged avoid talking about it as it brings them more harm than good. As a Muslim, I felt it a bit when house owners told me openly that they do not rent houses to Muslims in Mumbai and Kolkata. Even in “progressive” circles people take advantage of their social capital though in theory they advocate justice. Slowly with time, everything started becoming clear to me. I felt that anti-Muslim sentiment is a norm after a bad experience in Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta (CSSSC). Ambedkarism never tolerates identities, like our (savarna) liberals, but cherishes it. All cultural differences are cherished. During my interactions, even if there was a critique, I could easily sense that it was healthy. It was not to belittle the other, like Muslims.

Ambedkarism on campus

I felt that most Ambedkarite teachers believed that knowledge dissemination must take into account the ideal of equality. In an elite institution like TISS, many students struggle to cope with the English language, new environment and financial constraints. These teachers were sincere in trying to remove these impediments in learning so that education did not become elitist. Ambedkarism desires equality with respect to the production of knowledge. That people from all walks of life can produce knowledge is an important feature of this ideology, which makes it distinct from both Marxism and liberalism. It was from these Ambedkarite teachers that I saw the importance of understanding how a system excludes someone. Dalits’ critique of caste system, Muslims’ critique of Hindutva and women’s critique of patriarchy shows us we must lend a ear to the voices that are stifled. I have noticed how students who would never say a word in the class, started to speak out. Today, some of them are working for and writing about the inclusive idea of India, as envisaged by its founding fathers – Gandhi, Nehru and Ambedkar. It is here that I felt that knowledge production must involve as diverse a population as possible. I learnt that it is more important to listen to what a person is saying than to how he is saying it. One can have bad grammar but good arguments. Most elite education gives preference to form over substance, not so Ambedkarite education. Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of education came alive then, even though I had yet to hear his name then.

Ambedkarism in research: Lessons from UP

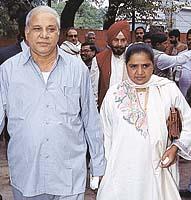

My fieldwork in Uttar Pradesh for MSW and MPhil led me to understand Dalit politics in Uttar Pradesh. I could see that Kanshi Ram is most the important figure here, and that he was a pragmatist while implementing Ambedkar’s ideas. Dominance of savarnas, mainly Thakurs and Brahmins, in almost all the spheres of public life became conspicuous to me. It was just as Kanshi Ram had said – that the top 15 per cent of the population had 85 per cent of the resources. Marx asked the working class of the world to be united; Kanshi Ram asked all the have-nots of Uttar Pradesh to come under the umbrella of Bahujan. Both his Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Samajwadi Party (SP) use this formula today. Social scientists keenly watch UP, where both SCs and OBCs have been successful in running their own political parties. “Ambedkarism” came alive to me through my fieldwork in UP, not through books and its apologists. Jai Bhim!

Copy-editing: Anil

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen