Surendranath Banerjea is one of the former presidents of the Indian National Congress and is remembered today as a prominent figure in the Indian independence movement. He was also among the second batch of Indians in the Indian Civil Service (ICS). It consisted of three Bengalis – Behari Lal Gupta and Romesh Chandra Dutt, apart from Banerjea himself. They qualified in 1871. The first Indian in “the heaven-born service” was Satyendranath Tagore, the elder brother of Rabindranath Tagore, who qualified in 1863. Banerjea, though, was the first to be dismissed from the Indian Civil Service, known as the steel-frame of the British administration and the predecessor of today’s Indian Administrative Service (IAS). The incident which triggered his dismissal and determined the course that his life would take, strangely, has rarely engaged public discourses.

Landing the dream job

The ICS deeply appealed to Dr Durgacharan Banerjea and his son Surendranath – the guaranteed immense prestige, power, and security of service with promotions. So much so, that under a “nefarious plot”, to quote Banerjea himself, his imminent journey to England for ICS examinations, was “carefully concealed from my mother, and when at last on the eve of my departure the news had to be broken to her, she fainted away under the shock of what to her was terrible news”. He sailed out of the country to chase his dream. Incidentally, the news of his father’s death on 28 February 1870 was withheld from the son, lest the news of the bereavement affected his preparations for the ICS examinations and frustrated the cherished ambition.

The initial cordiality between Sutherland and Banerjea soon evaporated, turned sour and was replaced by hostility. Sutherland, an Anglo-Indian, was “not very popular” which Banerjea writes, “I soon discovered.”

There was a third ICS officer, Posford, who was also an assistant magistrate in Sylhet but two years senior to Banerjea. Both the assistant magistrates took Departmental Examinations, which Banerjea passed but Posford failed. Following his success, the government vested the Bengali probationer with first-class magisterial power along with the usual pay increment. “My success was the cause of my official ruin,” Banerjea recalls. The district magistrate did not like that “I should have passed and that Posford should have failed.” Sutherland found it to be “derogatory to the prestige of the ruling race”. His relation with his junior deteriorated and the differences became irreconcilable.

On the face of it, this story sounds plausible. But even Bipin Chandra Pal, towering leader and a native of Sylhet district, described Banerjea unflatteringly – “the foolish and rather easy-going, young Bengali civilian whose unique position as a saheb had somewhat turned his head.” One of the politically astute triumvirate Lal Bal Pal (Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal), Pal was a teenager in 1871. In 1874, when Banerjea was ultimately dismissed from ICS, Pal matriculated from Sylhet Zila School. In other words, the sordid episode played out right before the eyes of this impressionable teenager.

The dismissal

Jaykrishna Kaibartta had filed a complaint against a fellow boatman/fisherman, Judisthir Kaibartta, accusing him of stealing a boat. The case was originally assigned to Posford but transferred to Banerjea for trial. “Owing to my heavy work,” claimed Surendranath, the hearing had to be postponed from time to time. On 31 December 1872, he passed an order, declaring the accused as “absconding”. Later, Banerjea explained that the accused Judisthir had not absconded and that it was merely an “artifice” to justify the long pendency of the case. “Artifice” is not something to be boasted of in judicial records. The artifice went against a poor boatman who expected justice from the court.

The Commission of Inquiry charged Banerjea with “dishonestly” entering “Judisthir’s name in the Ferari [absconders’] list, knowing that he was not an absconding prisoner …” He did not try the case. “I signed the order along with a heap of other papers,” Banerjea recalled. He was dismissed with a compassionate allowance of Rs 50.

An authority on public administration, Philip Mason, writes, “In the course of his first year, Banerjea sent in a false return. On one list he gave a full explanation for delays in dealing with the case – but the same case was included in another list of cases in which no action had been taken because the accused could not be arrested.” The Bengal Government held an inquiry by three senior officers, who found that “Banerjea had deliberately intended to deceive the Collector. The sentence was dismissal. Banerjea become a dismissed Government servant, branded for life.” A compassionate allowance of Rs 50 was sanctioned for him.

The colonial government had inflicted, bemoaned historian R.C. Majumdar, a major punishment on Surendranath for “a minor offence of a technical character”. Others claimed he was a victim of “racial discrimination”, implying that a white man would have escaped such major punishment and woeful consequence.

Let me cite two examples from colonial records to show that this couldn’t have the case.

Katwaroo murder

One Katwaroo, an “untouchable” Dusadh, from Bihar’s Saran district was in the employ of a highly successful barrister, Fuller, in Agra as a syce. One Sunday, he was not in attendance by his carriage while Fuller was to leave for Church for prayers. Enraged, Fuller screamed for his syce, who soon arrived before the master. The angry barrister assaulted the poor man, who fell to the ground because of the impact. Later, when he got up and went to his quarters, he was dead in a few minutes!

Barrister Fuller was charged under section 323 IPC for voluntarily causing hurt to the syce. His trial was assigned to Joint Magistrate Leeds, an ICS officer. Leeds examined witnesses, including the medical officer, who had performed the postmortem examination. He deposed that Katwaroo had died of rupture of the swollen spleen that could have resulted either from a blow or a fall. So, the accused was sentenced to pay a fine of Rs 30 or on default undergo 15 days of simple imprisonment. The fine was to be paid to Katwaroo’s widow. This was the infamous “Fuller case”.

Six months after this trial for the murder of Katwaroo, Lord Lytton arrived in India as the Viceroy (12 April 1876 – 8 June 1880). The tragic case of Katwaroo soon came to the notice of the Viceroy courtesy of a vernacular newspaper in Calcutta. An anguished Lytton took official note of the syce’s death. In his view, “the circumstances of a case” was “so injurious to the honour of British rule, and so damaging to the reputation of the British justice in this country” that he told the High Court to regard the death of Katwaroo as a consequence of violence of barrister Fuller. He wanted Joint Magistrate Leeds to be “severely reprimanded for his great want of judgement and judicial capacity.” He further enjoined that “Leeds should not be entrusted, even temporarily, with the independent charge of a District until he has given proof of better judgement and a more correct appreciation of the duties and responsibilities of magisterial officers for at least one year.” This indictment virtually sealed Leeds career.

The Viceroy also “severely censored the High Court and the Lieutenant Governor of North-Western Provinces because they did not think it their duty to take any notice of the Magistrate’s conduct”. This intervention by the supreme British authority provoked recriminatory responses, rarely witnessed or known in Indian history. The entire Anglo-India press came down “heavily on the Viceroy and abused him in no measured terms.” The judges of the Allahabad High Court “remonstrated with Lord Lytton and strongly recommended reconsideration of the case of the Joint Magistrate Leeds who tried Fuller.” The Viceroy “declined to remit the punishment which he had inflicted on Leeds and forwarded the remonstrances of the High Court to the Secretary of the State for disposal.”

Now Lytton turned his blazing fury at the Europeans living in India. He expressed his utter abhorrence at them for treating their Indian servants in a way they “would not treat men of their own race”. He called the treatment of Katwaroo as “more cowardly” because they were “least able to retaliate injury or insult.” So, the Viceroy warned them that “their habit of resorting to blows on every trifling provocation would be visited by adequate legal penalties, and those who indulge it should reflect that they may be put in jeopardy for a serious crime.”

The campaign to free Nabinchandra Banerjee

In 1873, the news of Madhavchandra Giri, the mahant of prosperous Tarakeswar Shiva temple being in an adulterous relation with Elokeshi, teenage wife of one Nabinchandra Banerjee, became a sensation without parallel in Bengal. When Nabin, an employee of Government Military Press, Calcutta learnt of the illicit relation, he, in a fit of rage, slashed a fish-cutter at his repentant wife’s neck, killing her instantly. The murderer surrendered to the local police and confessed the crime. In trial before British Judge Field, at the Hooghly District and Sessions Court, in Serampore, the Indian jury acquitted Nabin, accepting his plea of temporary insanity, but the British judge Field overruled the jury’s decision and forwarded the matter to the Calcutta High Court. Judge Field, however, accepted that there was an adulterous relationship between Elokeshi and the mahant, with whom she was seen “joking and flirting”. Justice Markby of Calcutta High Court also accepted the evidence proving adultery. The High Court convicted both Nabin and the mahant. Nabin was sentenced to life imprisonment while the mahant got three years’ rigorous imprisonment and was fined Rs 2000.

The verdict against Nabin caused an uproar in certain sections of Bengali society. The “members of the Calcutta elite and district town notables, local royals” and “acknowledged leaders of native society”, including the “lower middle class”, who numbered 10,000, launched a campaign for mercy for Nabin. The most outstanding Bengali patron of education, public charity and benevolence, Maharani Swarnamoyee Devi of Kashimbazar, was also involved in this campaign. After two years in jail, the convict was released.

Historian Tanika Sarkar boldly underlines the reason of the public activism favouring the convict. “Nobin was the poor and helpless Brahman. He was incidentally a purer Kulin Brahman more exalted in caste terms than the mahant whose precise caste status in his pre-ascetic life was in some doubt. Some thought that the unquestioned public sympathy for Nobin derived from this.”

Nabin murdered his wife in 1873; Surendranath Banerjea was dismissed from ICS in 1874; intervention of the Viceroy favouring Katwaroo took place in 1876.

Injustice anywhere, said Martin Luther King, Jr, is a threat to justice everywhere. The acknowledged leaders of native society, the Calcutta elite, though, were nonchalant about Jaykrishna Kaibartta being denied justice. The same people were vocal against the dismissal of Surendranath Banerjea from ICS. History has been distorted to cover up dismissed Banerjea’s gross incompetence and failure in dispensing justice. His error was not minor. In a caste-ridden society, injustice to the low-caste folk was almost routine. Leeds’ sentence was inadequate but S.N. Banerjea denied justice to Jaykrishna Kaibartta. Banerjea was so incompetent that he did not understand the significance of his own order declaring Judisthir Kaibartta an absconder. So, then, are the British to blame for his dismissal? Or is his own skewed sense of justice?

References

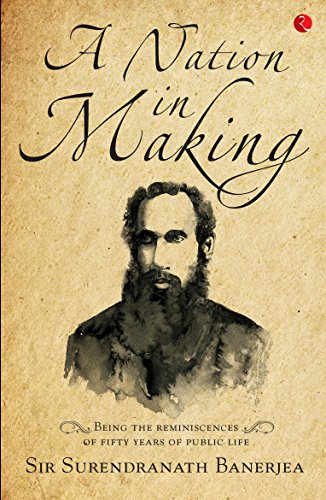

Surendra Nath Banerjea, A Nation in Making, OUP, 1925.

Bipin Chandra Pal, Memoirs of my Life and Times, 2nd revised edition, Calcutta, 1973, p 122; quoted by A.K. Biswas in Social and Cultural Vision of India, Pragati Publications, Delhi, 1996, p 182.

Philip Mason, The Men who Ruled India, Rupa & Co, Calcutta, 1992, p 252.

An Advanced History of India, R.C. Majumdar, H.C. Raychauduri and Kalikinkar Datta, Macmillan, 1990, p 848.

A.K. Biswas, ‘Common Man and Justice in British India’, Mainstream Annual, New Delhi, 1994

Tanika Sarkar, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, and Cultural Nationalism, Indiana University Press, 2002. Her comments are based on Bengalee (English), 22 July 1873, and Bangalbidyaprakashika (Bengali), 5 December 1873, quoted by A.K., Biswas, ‘Imaging the Hindu Rashtra’, in Mainstream, VOL LIII No 1, 27 December 2014 (Annual Number).

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History

Mahishasur: Mithak wa Paramparayen

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History