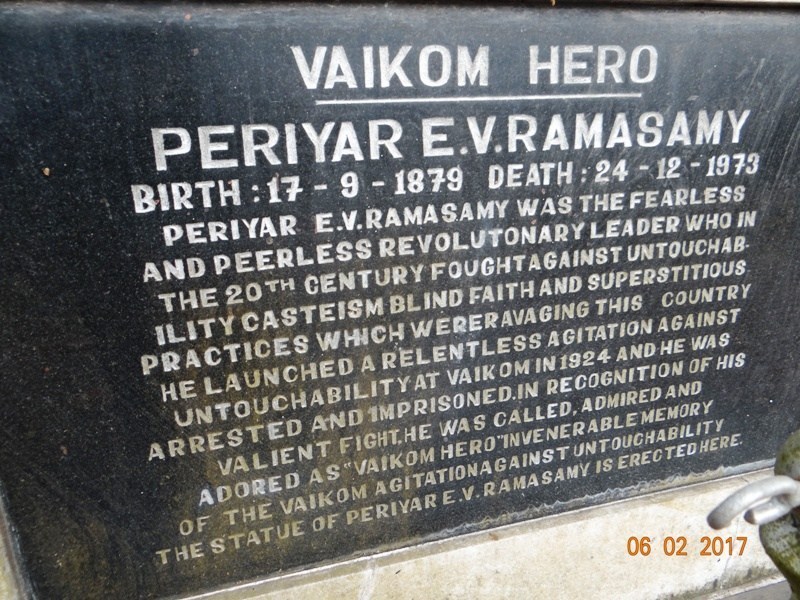

Periyar lived a long and productive life, active, literally, until the moment of his death, protesting the injustice that is caste and the Hindu religion, which, he believed, justified and sanctioned an unequal social order. This is how he explained his position, two years before he passed on:

“Though I have endeavoured all along to abolish caste, as far as this country is concerned, this had meant I carry out propaganda for the abolition of God, Religion, Shastras and Brahmins. For caste will disappear only when these four disappear. Even if one of these was to remain, caste will not be abolished in its entirety … because caste has been constructed out of these four … only after man had been made a slave and a fool would caste have thus been imposed on society. One cannot abolish caste without instilling a taste for freedom and knowledge [in the people]. God, religion, the Shastras and Brahmins make for the growth and spread of slavery and folly and strengthen the existence of caste” (Periyar: Ninety-third Birthday Souvenir, 17.9.71; Anaimuthu, 1974: 1974).

There were other versions of this argument. In the 1930s and 1940s, Periyar pointed to the three types of prejudices that one had to oppose, to build an equal, self-respecting and just society: of caste, religion and the nation. In some instances, Periyar added a fourth and fifth prejudice: to do with language; and with the set of ideas which justified the subordination of women, for instance, the doctrine of compulsory chastity, which kept women bound to unhappy marriages, and prevented them from exercising their emotional and sexual rights.

In essence, Periyar valued and upheld the rational and critical exercise of one’s mind, faculties and choice with respect to all aspects of life, from the personal to the political, and the social to the religious. He believed that all human beings were capable of such reflection. For him, “a taste for freedom and knowledge” defined one’s humanity and if one was not aware of this, then such awareness had to be instilled in all people. This was to be done through principled acts of criticism, of all that impeded one’s realization of one’s humanity, and by advancing a radical vision of social justice and equality. Often, this meant interrogating the claims of religion, and the arguments of those who liberally drew from religion to justify their social and cultural privileges and power. A critique of religion, for Periyar, was thus inexorably a critique of the social and cultural order which was sustained by religion.

***

Periyar’s critique of religion, particularly the Hindu religion, is often reduced to his atheism. But it had many aspects to it. Firstly, he held that it justified birth-based social divisions, and legitimized the caste order. All shastras, itihasas and puranas were clear with respect to this injunction – and Periyar argued that they were put in place to not only control and regulate the lives of “Shudras” and “Panchamas”, but to persuade them to “accept” their inferiority (Kudi Arasu [KA] 30.3.1926). Secondly, he noted that the Hindu religion refused learning to all but Brahmins. Others might learn a craft, or be proficient in their trade but they were not to be “educated” – that is, they were not permitted to ask questions to do with God or religious practices, indeed, refused the right to think and to develop critical concepts to appraise their world (ibid: 92). Thirdly, the Hindu faith valorized the role of the Brahmin, not only in his capacity as priest, but also in whatever secular role he sought for himself – for instance, it upheld the claims of Brahmins when they proclaimed themselves the “natural” intellectual leaders of society (KA 14.4.29; Anaimuthu: 255). It underwrote Brahmin support for nationalism, and the prerogative that the Brahmin bureaucrat or educationist sought for himself or herself (KA 19.5.29; Anaimuthu: 371-72).

Periyar’s critique of religions was of course not restricted to Hinduism. While he was drawn to the Islamic ideal of universal brotherhood and often suggested that religion as an option to those who wished to convert out of Hinduism, he was critical of how women within the faith were treated, and lively debates on gender and Islam were published regularly in Self-respect magazines (KA 14.10.1928; 25.11.1928) He was critical of Christianity as well, since it had accommodated caste-based divisions within its organizational structure, and invested the priest and church with overriding authority, to do with all aspects of a Christian’s life (KA 15.3.1936).

Periyar favoured Buddhism, and upheld its revolutionary role in history, but was not sure what it meant for one to convert to that faith. Thus, he wondered if it was wise for someone like himself to convert – since he would then be considered an “outsider” to Hinduism, and his critique of the latter would thus lose its charge (V. M. Subagunarajan, 2018: 360).

Periyar made it clear that he was not against systems of thought and practice which provided ethical directions to humankind, and this was also why he felt Hinduism did not serve its adherents well. For, it was not committed to universal ethics, or samadharma, a term that connoted equality and justice held in common, but instead favoured manudharma or birth-based privileges and penalties. In an address delivered in 1945 to a convention of the All India Backward Class Hindus, organized in Kanpur, he called upon all Hindus present to take note of the limitations and essential injustice of their faith and urged them to abandon it. He noted that one need not embrace a religious identity, simply because one was born into it. One could examine the claims of various philosophies and faiths and then make a choice – and in the process, one was likely to concede that reason, indeed, is the mother of all faiths! On the other hand, if one desired a broader identity, in place of what had been defined as “Hindu”, one could call oneself a “Dravidian”, since Non-brahmin Shudras were not considered “Aryans”. Or one could follow a “humanist” path, and consider oneself committed to “jeevakarunya”, that is, compassion towards all living beings. The important thing was to recognize that one cannot hope to reform Hinduism. Those who attempted to do so might earn a measure of credibility and respect for their views, but the structures of faith often remained untransformed. As he warned, even the Buddha had been coopted and displaced as is evident from the ways in which his ideas were accommodated into various puranas, itihasas and social customs; and reformers such as Ramanuja were made to do service to a vastly strengthened Hindu faith (V.M Subagunarajan: 257-263).

***

For Periyar, the problem was not only that Hinduism comprised a plethora of obscurantist beliefs and practices, or that it was irrational. It had actively re-invented itself in the modern period, as nationalism. Periyar argued that the rhetoric of nationalism had recourse to the language of faith, and this was quite dangerous. For the nation was invested with a mystical aura and nationalism discussed in such solemn and lofty ways and neither could be easily criticized. Brahmin nationalists had played an important role in thus defining nationalism – as something beyond interrogation and a self-evidently good and worthwhile ideal. On the other hand, they were unwilling to interrogate the social worlds that constituted the putative Indian nation: while they defined Swaraj as freedom from exploitative foreign rule, they did not speak up for Swaraj in social matters, or argue for freedom from old oppressive social customs, to do with caste, untouchability, gender and class (Revolt, 27.03. 1927; V. Geetha & S.V. Rajadurai, 2008: 34).

In his lifelong struggle against a compromised nationalism, Periyar followed two lines of critique: one, against the limited agenda of nationalism, and two, against the Hindu religion. The first line of critique culminated in the demand for a sovereign “Dravidian” nation – and all Non-brahmins and Dalits were invited to be part of it. While Periyar sometimes juxtaposed his demand for a Dravidian nation to the Indian nation, which he felt was the preserve of intruding “Aryans”, he did not really press this point except to call attention to the authority wielded by what he considered the “Brahmin-bania” combine. For him, the term “Dravidian” was, as he often noted, a valuable linguistic sign, an ideal term that defined the contours of a utopia, free of the bind of religion and caste. He did not deploy it in a racial or ethnic sense (KA, 25.6.1944).

Also read: Women called him Periyar or ‘the Great One’

The second line of critique was integrated with the first – Dravidian activists had to necessarily oppose the Hindu faith, which compromised their humanity and legitimized the power and authority of a birth-based minority. This minority, comprising “Aryan” Brahmins was viewed as alien, but, again, not in an ethnic or racial sense merely. Brahmins constituted a powerful social group, determined to uphold and sustain their social and cultural hegemony, in the teeth of all challenges to the latter. They were not inclined to therefore submit to a common or universal good. This was what rendered them “outsiders”. Their religion, too, was an imposition, since it served their interests, and affirmed their superiority over all others (KA 26.8.28; Anaimuthu: 249).

For Periyar, the struggle against Hinduism was an inexorable aspect of, and in fact, an essential aspect of the struggle for a Dravidian nation. Dravidian activists were expected to argue in favour of rational critique of existing social realities and this meant that they interrogate the Hindu faith. Critique as a form of struggle might not appear “political” enough and Periyar was aware of this. He argued that for the purpose his Dravidar Kazhagam had set itself, the creation of a caste-free society, the political sphere was both constrained and limited. For one, politics for him had to do with the here and now, with changing political conjunctures and circumstances. For another, political changes, including in forms of political rule, did not always transform social conditions, and in fact, most political formations tended to accommodate existing social conditions, rather than challenge them. And if they did seek to do the latter, they did so, within limits. It was therefore important to not think only in terms of political change or with accessing political power, rather one had to persuade and cajole society into thinking differently.

The imperative to social action did not mean Periyar was indifferent to the political entirely. He was keenly aware of what State power could achieve, and therefore remained a lifelong supporter of governments that endorsed social justice. Nor was he averse to persuade them to adopt policies that pertained to the latter. This was why he supported the Congress government of K. Kamaraj because he felt that Kamaraj had delivered on this count – accelerated modern economic and educational development and upheld reservation, even as he fought entrenched caste interests. He also saw possibilities in Nehruvian socialism that could benefit Non-brahmins and Dalits. This, in spite of his lifelong opposition to the national Congress, and its politics (V. M. Subagunarajan: 345-350).

Periyar was also not blind to how State power, if not constantly persuaded to the path of social justice, routinely took the part of the dominant castes. The Dravidar Kazhagam was particularly sensitive to how local government, particularly the executive could actually work in concert with dominant caste and class interests. Thus, through the 1960s, the Kazhagam under Periyar’s leadership demanded that Dalits be compulsorily awarded posts in local administration, particularly in police thanas and the revenue department, since these spaces were central to the play of local caste and political power. It also argued for Dalits to be awarded house sites in the heart of the village, in those very agraharams, or Brahmin neighbourhoods they were kept out of (V. M. Subagunarajan: 361-362).

Yet, for Periyar, the political remained only a side story. The main story had to do with religion and caste, and both had to be relentlessly and permanently criticized.

***

The relationship between Hindu religion and caste was self-evident to Periyar, as indeed it has been to generations of anti-caste activists. Hindu religion was nothing but an expression of the unequal caste order – its informing principle, its very life, in fact. Its texts defined and justified social difference and hierarchy, its practices sanctioned inhuman and barbarous customs which reiterated social lowness and highness; and its priests sought for themselves the sole right to interpret scripture and custom and thereby possessed the sole authority to manage spiritual matters in caste society, often to their advantage.

For Periyar, the religion-caste linkage existed at many levels: in the realm of knowledge and learning; in the arena of labour and occupations; and in the play of social as well as intimate relationships.

As far as knowledge and learning were concerned, historically, they were the prerogative of the Brahmin class, which guarded jealously its right to read and interpret the shastras, puranas, and the law books and refused to concede this right to others. Periyar argued that those whose lives were governed by Brahminical rules to do with good and bad were invested neither with the capacity nor the authority to challenge these rules or those who made them (KA 15.8.26; Anaimuthu: 11).

In the modern era, things had changed, and education was available to all, yet very few dared interrogate religion or religious custom. And, as before, the Hindu faith continued to determine what a person ate, how he dressed, his behaviour in public places, his social relationships – in short, it regulated all aspects of a person’s existence, from the sacred to the profane, the contingent to the transcendent. (KA, 9-11-46; Anaimuthu: 1197-98). Such regulations, Periyar noted, kept alive caste differences, rendered inequality palatable and ensured that those who rebelled against caste rules and religious strictures were punished. They also upheld untouchability, and justified its existence (ibid).

The failure as well as reluctance to question faith, Periyar argued, was because Brahmin authority in spiritual matters was seldom challenged. In order to take forward such a challenge, two things had to be done: understand that Brahmin authority with respect to religious or indeed all knowledge was arbitrary and asserted largely by themselves; and realize that the exercise of reason would dislodge the truth claims of Brahmins, with respect to spiritual and ritual matters. In an essay on the sacred thread, Periyar mocked at Brahminical pretensions to knowledge. He pointed out how the thread conferred normative worth and power on the Brahmin child, irrespective of its actual and material character. That is, even if a Brahmin child were to be born into poverty and destitution, it did not lose access to the thread, or the exalted status the wearing of the thread signifies. Whereas a child from another community, even if “clean” and “pure”, and well looked after, is denied access to the thread, and by that token, an exalted status. Further, whether a Brahmin wore the thread or not, or performed or failed to perform the rituals associated with it, he revelled in the exclusive status it granted him; on the other hand, even if a Non-brahmin were to seek the thread through acts of piety and learning, he would not be allowed to gain possession of it (KA, 27.12.25). The point was that Brahmin claims to knowledge and intelligence were based neither on their so-called merit, nor their aptitude – rather these claims flowed from the accident of birth, and the privileges that came with it.

In the face of Brahminical claims to knowledge and merit Periyar upheld the claims of reason. All human beings, he argued, were capable of rational thought, and possessed the discretion to weigh evidence, arguments and come to their own decisions and understanding of all matters, whether social or spiritual or political. Even as he propounded radical and critical views on politics and religion, caste and gender, Periyar entreated his followers to not accept his point of view, without rigorously examining his arguments. He often pointed to how in subsequent decades, his ideas might appear quaint and considered even worthless. For that was the way of knowledge, shaped by reason: open-ended, and critical. And Non-brahmins and Dalits must embrace such knowledge and use it to build a good and just society.

The Brahmin class’ appropriation of learning in the past, Periyar explained, had to do with the caste- based division of labour. This worked in two ways. Caste status determined wealth status: the rich and the privileged comprised “purohits, officials, lawyers, merchants, capitalists, zamindars and mirasidars”, all of whom were destined by virtue of their “high” birth to cultivate wealth and prosperity; whereas others, by the same token, were cursed to labour (KA 6.9.31; Anaimuthu: 1640). This exclusive class felt justified in its prosperity and exaction because the sacred books that it upheld ordained “a Shudra has no right to possess property” and “if a Shudra has property the Brahmins have every right to take it away from him by force”. Periyar pointed out that such conventional ideas had acquired worth and weight in these modern times because of Gandhi’s adroit re-definition of varnadharma ideas. Gandhi had enjoined that the village poor should not “seek to hoard wealth like the Bombay bania” but should instead “continue to labour honourably – grazing cows, making footwear” (KA 13.9.31; Anaimuthu: 1640-43).

Secondly, the religion of the Hindus had assigned particular forms of labour to particular groups such that they may perform these and none other. This system had been put in place through law, custom, and the coercive power of kings, who, throughout history, exercised their authority in these matters at the behest of the Brahmins (KA 14-4-29; Anaimuthu 255). Labourers thus worked at tasks they might or might not take to, and this meant that they did not view their work as either worthy or creative. Their sense of progress or growth, even in the modern age, was thus not determined by their economic condition, or their understanding of exploitation, rather it was shaped by their desire to socially upgrade themselves, by declaring that they belonged to this or that varna. Thus, “if a blacksmith or weaver attempted to Brahminize himself, an artisan would attempt to outdo him and covet the status of a ‘rishi’”. In other words, the pull of varnadharma was such that labourers remained “caste workers” rather than “wage workers”. Proletarian consciousness may thus not be built in the caste context, unless one challenged the caste system and the religious ardour that sustained it (Viduthalai [Vi] 16-2-40; Anaimuthu: 1748-50).

Further, Periyar noted, in a society organized around varnadharma, labour possessed no inherent worth or dignity. Even if necessary for survival, it was perceived as demeaning, and to make matters worse, the privileged refused to work and insisted on living on the fruits of another’s labour. This latter class of people also disdained manual labour and among them, the Brahmins were given to flaunting the claims of mental labour, of thought and learning, irrespective of the social relevance of such learning (KA 14-6-31; Anaimuthu: 1658-60).

Unless the religious sanctions that justified caste-based labour divisions were challenged, inequality and discrimination would remain, argued Periyar, and for the parties of labour this ought to be an important consideration. It would not do, Periyar noted, to merely repeat the observations of Marx, Engels and Lenin, as if these were instances of “revealed” truth. Socialists ought to understand their particular social totality for there were specificities to this society that neither Marx nor Lenin could be expected to know of in all its detail.

“… would Marx have known of the dominance exerted by the Brahmins of this country, of how they conspire to keep their authority intact? Would he have known that the native inhabitants of this land are considered Shudras – sons of slaves – by birth? That there exist here religious and shastraic lore to validate all this? Marx spoke of capitalism and its dominance, of how religion justifies capitalist exploitation in a particular context and really, it is neither fair nor just to expect him to have known of our situation” (Vi 20.9.52; Anaimuthu: 1746).

Not unlike Marx, Periyar reasoned that the end of caste-based labour practices required that we re-imagine labouring lives:

“Even if caste divisions emerged out of occupational divisions, why must such divisions exist at all? I want to know why a man cannot be a carpenter in the morning, a trader in the afternoon and teacher at night, and besides why he can’t be a person who can support another at the time the latter is being oppressed” (KA, 11.1.31).

Apart from shaping economic realities, pointed out Periyar, caste and religion influenced social relationships as well, and in profound ways. For one, the absence of self-respect made for unequal and disrespectful social relationships, including between Shudras and Dalits. Importantly, he urged those affected adversely by the caste order to also look to how they treated women – whose subordination, his movement argued, was necessary if the caste system was to sustain itself. Idealizing chastity, wifehood and motherhood, caste society had rendered women merely reproductive beings, and thereby secured its own existence (KA, 8.2.1931).

Periyar was aware that the caste system did not make for fraternity; that, in fact, it produced mutual suspicion and hatred; and that the Hindu faith and the hegemony exercised by Brahmins affected Shudras and Dalits in different ways. Untouchability was a distinctive condition, and had to be addressed in itself, even as it was to be understood in its relationship to the overall logic of caste. That is, it was not enough to abolish untouchability, the whole system of varnadharma had to go. Shudrahood was different, to be sure, in that Shudras were still “touchable” within limits – though, in the eyes of Brahmins they too were considered low and unworthy. But, as Periyar pointed out, Shudras did not appear to realize the precariousness of their situation, and, on the one hand, sought to, imitate Brahmins, and on the other hand, to set themselves apart from Dalits. Addressing Shudra antipathy to Dalits, Periyar noted:

“Among the non-Brahmins there are many who observe caste differences. But if you wish the upper castes to consider you their equals then you must grant that the caste below you is equal to yourselves. Sometimes it seems to me that the caste oppression we perpetrate is greater than that practised by Brahmins.” For, “the Nattukottai Chettis who have amassed such immense wealth choose to spend it on the study of Vedas, a vocation that prepares one for lifelong beggary! They thus not only feed Brahmins but encourage them to study. If they were to use this money to educate a few Adi-dravida children the latter would not be forced to undertake a coolie’s job at such a tender age” (KA 9.12.28; Anaimuthu: 332).

On another occasion, Periyar wrote in exasperation:

“When we speak of Adi-dravidas, it is understandable that Brahmins get annoyed. But it is incomprehensible to me that non-Brahmins too should be dismayed. This is but foolish and dishonourable. If you feel really humiliated by the fact you are considered ‘Shudras’ would you even for a moment feel uneasy when we claim that pariah-hood should be abolished?” (KA 11.10.31; Anaimuthu: 60)

Periyar also pointed to the futility of Shudras seeking to “upgrade” themselves, within the existing social order. For:

“Each caste group may discover and produce proofs of its own superiority but yet such proofs will only serve to illustrate the fact that all castes are inferior to those who call themselves Brahmins” (KA 30.11.30; Anaimuthu: 1599).

To counter this process of social imitation, Periyar counselled that Shudra castes modernize themselves, through education, the boycott of Brahminical rituals and Brahmin priests, and through endorsing their women’s rights to equality and learning. They were also exhorted to embrace technological progress, given that they were skilled artisans and stood to gain by advances in science (V. M. Subagunarajan: 119-121). Through the 1940s, he entreated them to abandon Hinduism – given that India would soon be free, and be ruled by Brahmins and Banias, by walking out of Hinduism and embracing a secular “Dravidian” identity, they could yet save their self-respect and realize freedom and equality.

Periyar’s addresses to Dalits were different: he called upon them to assert themselves, be defiant of local-caste power and authority, and abjure Gandhian institutions. He also enjoined them to exit Hinduism and embrace, if necessary, another faith that was likely to accord them justice and consider them equals. At the same time, he assured them that Shudras might consider themselves better off, but actually they were not, since caste society considered them “dishonourable”. That is Brahminical scripture and law defined the Shudras as born to “a slave, prostitute, a concubine, a born slave, one who has been raised as a slave” (KA 16.6.29; Anaimuthu: 57).

A good example of how adroitly Periyar and his movement handled Shudra-Dalit interactions may be cited here: this had to do with the infamous Devakottai injunctions, imposed by the Kallar community (today designated a backward caste) on Dalits, in the wake of their assertion. Periyar brought up this issue at the first Self-respect conference convened in the region, and presided over by elders from the well-endowed mercantile Chettiar community. A resolution was passed that condemned the violence and people from Shudra communities responsible for it and also asked for a committee to be set up to inquire into the troubles. Importantly, the same resolution also recorded its appreciation of those among the Shudra castes who had refused to impose social sanctions against Dalits. Speeches at the conference also endorsed Dalit rights to equality (V. M. Subagunarajan: 193).

While clear that the annihilation of caste demanded different things from Shudras and Dalits, Periyar yet sought to build a community of self-respect, and later a Dravidian fraternity which would bring them together into a new culture of comradeship – to be achieved through conscious renunciation of Hindu beliefs, practices and the equally conscious embracing of a new way of life, central to which was the practice of intercaste marriages, the acceptance of women as comrades, and sustained support for women seeking to make their own life choices, whether in the realm of work, family or in intimate relationships.

The fraternity of Shudras and Dalits was neither easy to build nor sustain, since it was often undercut by material relationships, of power, property and labour. Further Shudra communities that heeded his call to modernize themselves did not always take seriously his call to fraternity. Individuals, sometimes large numbers of them, from various Shudra castes were in the forefront of struggles against untouchability and supported intercaste marriages, especially between Shudras and Dalits, yet there was a substantial section of the Shudra population that took his critique of Brahmin power to heart, but not his call to them to accord absolute equality to Dalits.

Periyar’s insistence on women being coeval and equal to men was not always heeded – and this has been the hardest ideal to sustain though, here, again, there were masses of men and women who attempted to practise a different sort of intimate and familial life – based on mutual respect, equality and shared political beliefs.

***

Periyar’s critique of Hinduism was seldom negative. He simultaneously advanced and propagated his and his fellow workers’ vision of the good and just society. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, when he was still active in the Indian National Congress, Periyar understood the good society as one that could be built on the basis of constructive action. He was drawn to Gandhi’s three-point programme – the abolition of untouchability, temperance and the cause of khadi. But he was disillusioned when Gandhi endorsed the decision of a section of the Congress – the so-called Swarajists – to abandon Non-cooperation and enter legislature. He felt the three causes that he considered important, being consequential to the lives of Non-brahmins and Dalits had been compromised. His disillusionment with Gandhi grew, when the latter proclaimed with equal ardour, his commitment to ending untouchability and to the upkeep of varnadharma. Periyar wrote: “If the body of varnashrama dharma did not exist, untouchability which constitutes the very life of this body would not be alive today”. And therefore, “ … if we are to follow the Mahatma’s untouchability creed, we will slip into the very abyss of that Untouchability we are attempting to abolish” (KA 7.8.27; Anaimuthu: 76-77).

This disenchantment with Gandhi led Periyar to outline his own principles on caste, untouchability and the good society. Even when in Congress he had made it clear that the demand for Swaraj had to be balanced with the rights of those who were denied their rightful place in education and government, and with the needs of the so-called Untouchables: “We refuse to grant [to the Untouchables] even those rights we readily grant to dogs and pigs. In our context is Swaraj a necessity? The public must ask itself what is important – Swaraj or the progress of and the attainment of self-respect by the Untouchables?” (KA 31.1.26; Anaimuthu: 450). Subsequently, he wondered what could be the meaning of Swaraj in a society that was lacking in self-respect:

“Tilak claimed that Swaraj was his birthright, but since he was a varnashrama Brahmin, and since such men hold that others are inferior to Brahmins, this sentiment, in itself, becomes their birthright. It is, on this account, that Tilak was forced to use a term `Swaraj’ – useless for this purpose and dubious in its implications for practice – drawn from the field of politics to refer to his birthright. But we are not constrained to survive by deceiving others. Instead, we are intent on discovering humanity in its truest sense. Therefore we maintain `self-respect is a man’s birthright’. We must realize that Swaraj is possible only where there is already a measure of self-respect and is otherwise not a discernible entity in itself” (KA 9.1.27; Anaimuthu: 3-4).

The creed of self-respect was proclaimed loudly in the decades that followed and it was soon evident that it was opposed to both the politics of Swaraj, as well as the religious rhetoric and ideals that sustained this politics. On the one hand, Hindu religious beliefs and customs were not only criticized but alternative ways of being and living outlined. As the Self-respect movement gained ground under Periyar’s leadership, its members, both men and women, spoke of the need for new human ideals, transformed human relationships and called for a radical rethinking of intimate and domestic relations.

On the other hand, nationalism and nationalists were not spared either: Nationalism (as noted above) was criticized for being a veritable new religion, presided over by a novel political dictator, Mahatma Gandhi, whose persuasive talk had lent this religion a certain mystical aura.

“His religious guise, god-related talk, his constant references to Truth, Non-Violence, Satyagraha, cleansing of the heart, the power of the spirit, sacrifice and penance on the one hand and the propaganda his disciples and others – nationalists and journalists –who in the name of politics and the nation consider him a rishi, a sage, Christ, the Prophet, a Mahatma and a veritable avatar of Vishnu on the other, along with the opportune use of Gandhi’s name by the rich and the educated … have together made Gandhi a political dictator” (KA 23.7.33; Anaimuthu: 389-90).

Periyar was critical of the quintessential Gandhian form of protest, the satyagraha. He argued that it served to bully people into accepting a certain understanding of truth, and was, therefore, morally ambiguous. Further satyagraha might not work in all those instances where justice stood to be established: it would not help Dalits acquire land or a share of the wealth that was held by religious institutions and temples. Neither would satyagraha prove successful against zamindars and merchants and kings who were determined to keep their working population captive to their interest and who gave them enough only so that they may live to labour (KA 6.9.31).

In contrast to Gandhian piety, particularly his practice of satyagraha, and nationalist politics, in general was the Self-respecter’s creed, founded on dialogue, persuasion and argument. Periyar noted that as opposed to claiming to speak and act in the name of an ineffable truth, Self-respecters sought to persuade rather than force a change of opinion. They had travelled from town to town, from village to village, holding meetings, prevailing upon the public to listen and if convinced, heed their words. But they had not sought to explain and interpret their ideas to suit the occasion or the context. This mode of public debate, implied Periyar, was in stark contrast to the habitual Congress mode of conducting its public and political campaigns. Congress was interested in displays of power and sentiment, it was given to shows of defiance against India’s imperial rulers and was clearly interested in rousing rather than educating people’s sentiments and feelings on matters of import to them (ibid).

In the 1930s, Periyar and the Self-respecters, outlined their philosophy in even greater detail, aligning themselves with socialist ideals, and also expounded a powerful and critical atheism. Their implacable opposition to Congress nationalism remained in place and acquired an even more critical edge, in the wake of Gandhi’s epic fast and the subsequent signing of the Poona pact. This was also when they examined in detail the limits of the communist movement in India, especially the latter’s reluctance to consider the annihilation of caste as a central and necessary aspect of their politics (KA 25.3.44; Anaimuthu: 1711-13).

Meanwhile, their critique of Hinduism continued, and acquired a sharp focus in the 1940s, as the British prepared to transfer power to Indian hands. The attempt by the Congress government of C. Rajagopalachari to impose the study of the Hindi language, during his term as Prime Minister of Madras Province (following the elections of 1937 elections, he was elected Prime Minister), became an enabling context for Periyar and his comrades to mount a wholesale attack on what eventually came to be termed “Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan’, or the idea of India, which accepted the leadership of Brahmins and banias, and which sought to impose a single language and culture on a diverse population. Hindi was objected to because it was linked to Sanskrit, and therefore viewed as a carrier of puranic values (KA 22.8.37). However, as we have noted above, Periyar was not given to racial or ethnic reasoning, though he did resort to it, at times, and for him the question of Hindi was problematic, largely because he understood the imposition of Hindi to be a Hindu nationalist measure.

The demand for a Dravidian nation emerged in this context, but as noted above, it was less an ethnic or racial ideal, and more a utopian one – the new society, as Periyar made clear in several speeches during the 1940s, would be essentially a caste-free one, and one where Hindu ideals would not command life or consciousness. Further, such a society would be run on cooperative and socialist principles.

The demand for Dravidian nationhood and Periyar’s call to Non-brahmins and Dalits to exit Hinduism persisted even after India became independent of British rule. Periyar read the Indian legal and constitutional systems to be flawed because they had not explicitly pronounced against caste – even as the Constitution declared untouchability to be abolished – and he held that the Constitution actually protected existing caste arrangements. A Madras High Court judgment which struck down an existing government order to do with reservation – and which was upheld by the Supreme Court – provided an occasion for him to demand that the government endorse affirmative action. Widespread protests through 1950 finally resulted in the first amendment to the Constitution (Ananimuthu, 2009: cxlviii-cxlix).

Periyar remained watchful of the manner in which the government of India transacted the Constitution, and especially of the functioning of the largely Brahmin bureaucracy. Following a series of protests against the latter’s alleged nepotism, the Dravidar Kazhagam undertook a campaign in 1957 to burn those articles of the Constitution, which, they held, protected the existence of caste and rendered the Brahmin bureaucrat insuperable (ibid, clvi-clvii).

Through the 1960s, the Kazhagam kept up its critique of caste, Hinduism and the nation – this, when, as mentioned earlier, he was supportive of Congress rule in Tamil Nadu!

Fittingly enough Periyar’s last battle had to do with securing for Non-brahmins and Dalits the right to become temple priests in agamic temples, traditionally presided over by a Brahmin priesthood. In 1970, the Government of Tamil Nadu, then under the rule of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) with M. Karunanidhi as Chief Minister, introduced amendments to the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act – Tamil Nadu Act 2 of 1971 – in the Legislative Assembly to do away with the practice of appointing archakas (temple priests) on a hereditary basis in over 10,000 temples, permitting persons from all castes to be eligible for the posts of priests. For Periyar, this seemed a matter of urgent import, for he had all his life held that it was the Brahmin’s time-honoured relationship to sacrality that granted him his exclusive identity and prowess. The Tamil Nadu Legislature passed the amendments, which were then challenged in the Supreme Court.

The five-judge bench of the Supreme Court accepted that the matter of appointing priests had evolved out of secular imperatives and there was nothing sacred about this practice. But the Bench refused to accept the consequent argument that priests could henceforth be appointed from all castes. It was argued that such a practice, if instituted, would be a clear violation of agamic injunctions which were very severe with respect to the conduct demanded of a prospective priest. Further, if such injunctions were to be wilfully ignored, this would mean a direct interference with the Hindu worshipper’s practice of his faith. The Bench observed that for the Hindu, the idol was a sacred object of immense significance. The devout Hindu would not countenance anyone but a traditional priest to touch the idol, for his faith was clear on this matter. Further, “any State action which permits the defilement or pollution of the image by the touch of an Archaka not authorised by Agamas would violently interfere with the religious faith and practices of the Hindu worshipper in a vital respect and would therefore be prima facie invalid under Act 25(1) of the Constitution” (AIR 1972: 1592-93).

Needless to say, such sentiments angered Periyar and confirmed him in his opinion that the Indian nation was not interested in all those who were condemned by the Hindu religion to be less than human simply because they were not Brahmins. The circularity of this kind of reasoning proved particularly bothersome to Periyar, who sensed there was really no way out of it. The learned judges of the Supreme Court had, after all, quoted without demur P. V. Kane’s reference to Brahma Purana: “when an image . . . is touched by beasts like donkeys . . . or is rendered impure by the touch of outcastes and the like . . . God ceases to dwell therein.” Further, the Bench had unequivocally stated they were duty-bound to protect the freedoms guaranteed under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution:

“The protection of these articles is not limited to matters of doctrine or belief, they extend also to acts done in pursuance of religion and therefore contained a guarantee of rituals and observances, ceremonies and modes of worship which are integral parts of religion … what constitutes an essential part of a religion or religious practices has to be decided by the Court with reference to the doctrines of a particular religion and include practices which are regarded by the community as part of its religion” (AIR 1972: 1593).

Under these circumstances, Periyar raised the slogan of a separate Tamil Nadu, which as before, was to be less an ethnic and political domain, and more a place, where varnadharma could be abolished and equality and social justice established.

This was in 1972, a year before he passed on. He was past 90 years, and yet ready to fight – as he remarked, the fight against caste was neither easy nor was it going to end very soon. He was modest about what had been achieved, and conscious of what stood to be done: after all, to annihilate caste was a task that demanded superhuman effort. As he remarked many a time during the last decade of his life, it was akin to overturning a mountain, he noted, with a lock of hair! Yet, Periyar was neither cynical nor in despair. He saw himself in his later years as a tree that had shed all its leaves – he had nothing to lose, and meanwhile, there was everything to gain by speaking out against caste and for self-respect and samadharma.

REFERENCES

Books

Anaimuthu, V., ed, Periyar E. Ve. Ra. Sithanaikal (Thoughts of Periyar), 3 vols Sinthanaiyalar Pathippagam, Trichinopoly, 1974. (Reissued in multiple volumes as part of a limited edition, 2009).

Geetha and S.V. Rajadurai, ed Revolt: A Radical Weekly from Colonial Madras, Periyar Dravidar Kazhagam Publications, Chennai, 2008 (Periyar Dravidar Kazhagam has since been renamed Dravidar Viduthalai Kazhagam)

M. Subagunarajan, ed Namakku En Indha Izhi Nilai? Jati Maanadugallillum Jati Ozhippu Maanadugallillum Periyar (Why are we in this Degraded position? Periyar’s speeches at Caste and Caste Abolition Conferences), Kayal Kavin, Chennai, 2018

Other Sources

Kudi Arasu (KA); Viduthalai (Vi); Revolt: Publications of the Self-respect movement and the Dravidar Kazhagam.

AIR – All India Reporter (Database of Judgments).

Note

- a) All translations from Periyar’s writings are by V. Geetha and S. V. Rajadurai.

- b) For a comprehensive history of the Non-brahmin and Self-respect movements, 1926-1938, see V. Geetha and S. V. Rajadurai: Towards a Non-brahmin Millennium: from Iyothee Thass to Periyar, Samya, [1998], 2008.