Manoranjan Byapari came into the limelight after the publication of his autobiography, Chandal Jebon, in 2012. On 14 September, 2020 he was appointed chairperson of the Bangla Dalit Sahitya Academy by the Mamata Banerjee-led Government of West Bengal. Byapari had come to India as a refugee from East Pakistan just before the 1971 Indo-Pak war. In 1975, when he was just 20, he was arrested for participation in a political event. He learnt how to read and write during his stay in the jail. After his release, he started driving a rickshaw. His meeting with Mahashweta Devi, a literary giant of Bengal, was the turning point in his life. From a rickshaw driver he became a litterateur. He worked as a cook in a government school to make ends meet. But that did not come in the way of his work as an author. Chandal Jebon was followed by a novel, Batashe Baruder Gandho (Smell of gunpowder in the air), which was well received. Last year, the English translation of this novel was selected for the DSC South Asian Literature Award. Edited excerpts of his conversation with Kartik Choudhary:

How do you define Dalit Literature?

Those who were oppressed by the Indian Varna system are called Dalits. Dalit is a broad term. People are trampled upon for no fault of theirs – just because they were born into a low caste. They have to suffer all kinds of privations. Their only crime is that they belong to a caste which has been categorized as “low” by the Varna system. Hence, whatever has been written about the upliftment of the exploited majority is Dalit Literature. I believe that the literature that talks of an egalitarian society is Dalit Literature.

What is the basis of writing Dalit Literature?

The main basis of the subject matter in Dalit Literature is (the lack of) food, clothes, education, housing, healthcare and respect. Whatever is written around this would qualify as Dalit Literature.

Consciousness is the core of Dalit Literature. How would you define it?

Consciousness is the focal point of Dalit Literature. It helps to identify the mindset of the writer. Many from our community have become well-known writers. But they are writing about flowers, waterfalls and romance. This is due to the lack of consciousness. It was because of the growth of Dalit consciousness that we are able to pinpoint the lacunae in the works of Savarna writers based on the life of the Dalits. Take Premchand’s Kafan or Manik Bandhopadhyaya’s Padma Nadeer Majhi. Until we didn’t have Dalit consciousness, we admired these works to no end. When we developed Dalit consciousness, we were able to identify the omissions and the commissions and even the vices in them. We believe that if someone has Dalit consciousness, he can save himself from these pitfalls. That is why before talking about Dalit Literature, we need to talk about Dalit consciousness.

Do you agree with the contention that Dalit Literature is about the hidden meanings, the implications of words?

Dalit consciousness will make us alive to these issues and we will be able to understand the concepts behind words. Just look at the idiom “chori-chamari”. The correct word is “chori-chakari” but “chamari” is associated with a caste. It is the Varma system which has led to such distortions. And we all use such words. But why? There is a word “khisti-khamari” in Bangla. It is a term of abuse. “Khisti” is fine but the word “khamari” is associated with “chasi” (farmer). The seeds of wheat, paddy, etc, that the farmers store is called “khamar”. Now, farmers are those who live by the sweat of their brow, those who toil, those who do back-breaking labour. We will have to analyze in depth the hidden meanings, the implications of the words. Who added what to an idiom, to a word, to a saying – we will have to find out and also the motive behind it. We will have to steer clear of such words. And we will have to cull these words from literature.

You mentioned Premchand. Which of his stories you don’t agree with?

Kafan is a story which is much talked about. It is said to be a story on and about Dalits. But what I object to is Ghisu and Madhav being introduced as Chamars and drunkards. Now, drunkards have no caste. They can come from any caste. Of course, this doesn’t mean that Premchand was not sensitive to the plights of the Dalits. But he chose a Dalit because he wasn’t one himself. If we rewrite this story, we won’t use the words that Premchand has used. And even if we portray them as drunkards they definitely won’t sell the kafan (shroud) to buy liquor. In our version of the story, on seeing food being cooked in a hotel, Ghisu and Madhav (father-son duo) will say that the one who has died is gone. “Let us eat so that we can survive for one more day.” They will sell the shroud and buy food. They won’t drink liquor.

What will be new in Bangla Dalit Literature?

Bangla Dalit Literature will be a literature of humanity. No writer will be a god and none will be demeaned. They will be presented just as they are. Ours will be a new literature. We will not necessarily write what the upper-caste authors are writing – we won’t copy their style. We will start a new stream.

Tell us about the origins of Bangla Dalit Literature.

The beginnings of modern Bangla Dalit Literature can be traced to the Jagran magazine, which came out in 1911. You can also go back a little further and say that it began with Charyapad.

It is often said that anger is missing from Bangla Dalit Literature. The Bangla Dalit writers do not put anyone in the dock. Your take?

That is not true. Anger and rage are bound to be there. Who will be angry? Obviously, the one who is deprived, the one who is facing privations. Right from Rabindra [Nath Tagore] to the present day, the writers have been a happy and contented people. Why would they seethe with anger? The Dalit litterateurs and others who wrote Dalit literature – both were a contented and happy people. The words they chose to express themselves reflected their state of mind. But Dalits have become conscious. Now, anger is bound to seep into their literary writings. Just see any of my works. It is suffused with anger.

Who or what is responsible for this seething rage?

Capitalism, patriarchy, Brahmanism, casteism, communalism. Dalit literature is committed to uprooting each one of them. Till they disappear, rage will continue to be a part of Dalit Literature.

In an interview with FORWARD Press, you had said that in Bengal, Dalits won’t allow anyone to throttle them. Will this happen in literature alone or also assume the form of a movement?

Literature and movement are complementary to each other. If there is a movement, it will echo in literature. And literature lends strength to movements. Dalit Literature will play a key role in the Dalit movement.

Do you think Dalit Literature has got adequate recognition in Bengal?

There is a debate under way in Bengal now, the issue being whether my works should be given any importance. Some say what I have written is literature. Others say it is not. I have written 22 books so far. When I was asked about it, I said that I have been writing for 40 years now. What I wrote was liked by the readers. Whether my writings are literature or not is of no consequence for me. What matters to me is that there is truth in them. No unrealistic story can stand up to truth. This is the reason I have been able to build my identity. Every effort was made to smother me. And that continued till recently. Now, I have been appointed chairman of the Dalit Literature Academy. I have been given this important position. But we had to fight for it. It was not that it was offered to me on a platter. They had to give it because we did not tire even after struggling for 40 years.

How do you view the concept of Bhadralok?

This is an old concept in Bengal. Society was divided into Bhadralok and Chotalok. The Bhadralok no longer wear the janeyu (sacred thread) but their mindset remains unchanged. They still consider themselves superior. Chotalok, of course, come from the lower tiers of society. They may include some upper castes but very few. This concept exists in literature, even in Dalit literature. That is why the established Dalit magazines of Bengal did not give me place. Bhadralok includes doctors, professors, engineers and the like. But not people like me. They would fall from their high pedestal if they published the writings of illiterate rickshaw drivers like me. This is also a part of the concept of Bhadralok.

Who are your favourite authors?

There are four. The first is Mahashweta Devi. I love her anger. She does not put up at all with atrocities against the farmers, the labourers and the Adivasis. Second, Shamresh Basu, who crafts every character in his works very lovingly. Third, Vinay Mukhopadhyaya who uses the pen name Yayavar. His novel Dristhipaat impressed me a lot. For him, words are like gems, to be threaded to form a beautiful necklace. Fourth, acclaimed Hindi writer Shrilal Shukla. I have read his Raagdarbari more than six times. I feel like reading it again and again. I like his style immensely.

What is on your agenda as the chairperson of the Dalit Sahitya Academy?

First, there will be a library of Dalit Literature. Bangla Dalit Literature will be translated into other languages and the Dalit Literature of other languages will be rendered into Bangla. Young Dalit writers will be given due importance. Dalit Sahitya Academy will have its own magazine. There will be distribution centres for our books. Meetings of the distributors will be held from time to time.

When you were appointed chief of the Academy, Hindi critic Chauthiram Yadav had described you as a “Working Dalit writer”. Your comment?

This title suits me. I am indebted to Chauthiram ji for showing me such regard.

Your message for young Dalit writers?

My message to them that they shouldn’t write “happy literature”. Understand society and courageously bring the truth before the people. Read Babasaheb Ambedkar, read Jogendranath Mandal. There are others to write on flowers, leaves and love.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

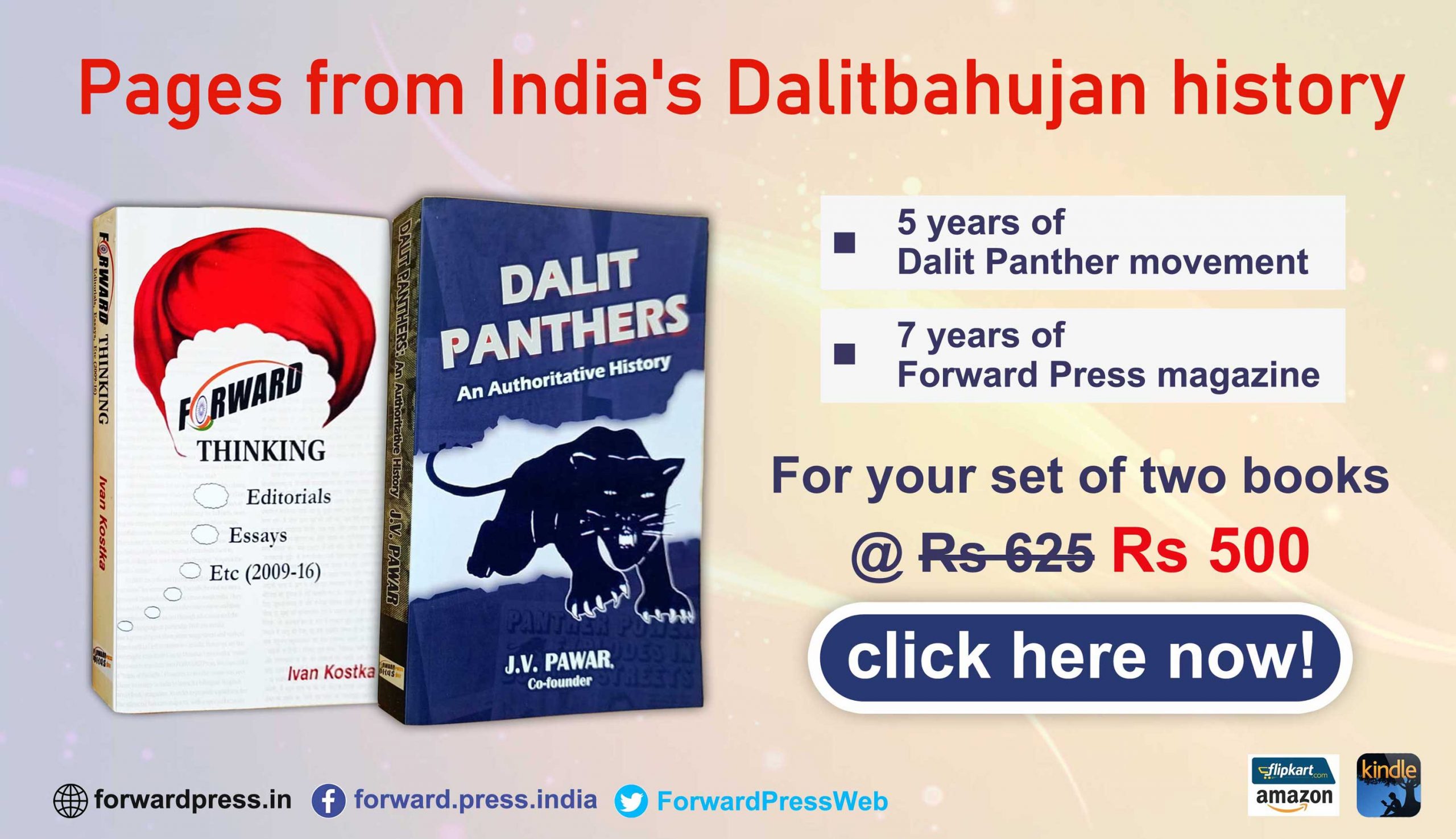

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History