Phanishwar Nath Renu (4 March 1921 – 11 April 1977)

To establish oneself as an exemplar among one’s contemporaries in any creative field is a rare achievement. Epoch-making Hindi author Phanishwarnath Renu was one who achieved this feat with considerable ease.

Renu was born on 4 March 1921 at Orahi Hingna village of Araria (then Purnea) district of Bihar. Underlining that the literary prowess of Renu was beyond compare, Nirmal Verma wrote:

“Renu was the most important among those whom I kept in mind while writing … Some people are like a censor to us – no, not the censor of the powers that be, which invokes fear but a censor which acts on our soul, on our conscience and which links up with the morality of our creative expressions. That Renu was there – the mere fact of his presence – was both a boon and a restraint.”

What lends an even greater significance to this quotation is that Nirmal Verma is a leading writer of contemporary Hindi fiction and an avid scholar of world literature. Such a person remembering Renu – the flag-bearer of indigenous identity – as a “saint-writer” is enough to underscore the fact that Renu was a litterateur of and for all times. Besides Nirmal Verma, Raghuvir Sahay and Agyeya also accepted that Renu’s creative commitment, and his pro-people orientation were like a beacon for them.

Which elements in Renu’s writings made him so famous and respected, not only among his contemporaries, but also among the common readers? Renu believed in walking the talk. He wrote about how the “sons of the soil” lived, about the paradoxes, the struggles, the joys and the sorrows that informed their life. He was probably the first Hindi author to so vividly depict the likes and dislikes, the love, the pain and the pathos of the common man in his writings. He bared their souls.

Renu began his literary journey in 1944, when he was barely 23. His first short story “Batbaba” was published in the magazine Vishwamitra, published from Calcutta that year. The debut work of most litterateurs largely remains unrecognized, and so it was with Renu. But against the backdrop of the environmental challenges facing the world today, amid the talk of eco-literature and the intense discourse on preservation of the environment, “Batbaba” eminently merits a re-rendition. The story is centred on an ageing banyan tree, which the villagers address respectfully as “Batbaba”. The banyan tree is in attendance in all their festivals and celebrations, it is there in their sorrows and their joys, in their wishes and their aspirations and in their mutual interactions – such is the abiding affection they have for it. The tree comes to symbolize the cultural identity of the village and its denizens. Then, one day, the tree dries up and the landlord decides to hack it down to make up for the shortage of fuel wood. As the news spreads, a pall of gloom descends on the village.

The words Renu uses to describe the grief that engulfs the villagers exemplifies a high degree of sensitivity towards environmental protection. Renu brings alive even the pain and the distress of the dogs, cows, bullocks, horses, goats and birds which found sanctuary in the tree. Depicting the pain of the villagers, he writes, “Some men were crying bitterly as if the axe was hacking their hearts into pieces.”

The collective agony of the villagers on the felling of Batbaba symbolizes the high value Indian society attaches to trees. When this short story was written, global warming and climate change were unheard of; but the way the writer has underlined what the loss of a tree entails for humans and what its cultural and social fallout are, finds a resonance in the modern concern for the environment. An elderly character mirrors the modern man, condemned to dwell in concrete jungles – “Has the BatBaba dried up? … This is the end of the world.” The story, with its deep and abiding implications, connects superbly with the scientific predictions about what life without trees would translate into. It would not be an exaggeration to say that “Batbaba” sowed the seeds of the historic “Chipko Movement” launched in independent India to save trees by hugging them.

In this context, Renu’s classic novel Parti Premkatha also deserves a mention. This novel is about the emergence of a new world from barrenness. The protagonist, Jittan, decides to grow trees on his vast swathe of barren land. He uses his limited knowledge of ecology to identify the trees which can be grown on barren land and decides to give it a green cover. Jittan symbolizes the significance of communal efforts and sustainable lifestyle for preserving the environment – something that we desperately need today.

In today’s consumerist world, achieving professional targets by hook or by crook defines success. And that has rendered values like sensitivity, compassion, sacrifice, love and community feeling meaningless. In these gloomy times, short stories like “Samvadia”, “Thes”, “Rasool Mistri”, “Maare Gaye Gulfam”, “Raspriya”, “Jalwa” and “Jadau Mukhda” can light up the path of the new generation, steeped in corporate culture. These stories forcefully convey that preserving humanity and social concerns is more important than achieving professional success. Hargovin is a samvadia – who works as a messenger for a living, but is unable to convey the message he has brought for the parents of Badki Bahuria (elder daughter-in-law), though this is his profession. He says, “Forgive me, Badki Bahuria. I could not convey your message. You shouldn’t leave the village. I won’t allow you to suffer. I am your son. Badi Bahuria, you are my mother. You are the mother of the entire village. I will no longer sit idle. I will do all your work.”

Hargovin fails to discharge his professional duty but he manages to save the ties of love and affection that connect humans from coming apart. That is more important than achieving the biggest of “targets”. The same is true of other characters like Rasool Mian, Heeraman, Panchkaudi, Mirdangia, Fatimadi and Dr Umesh.

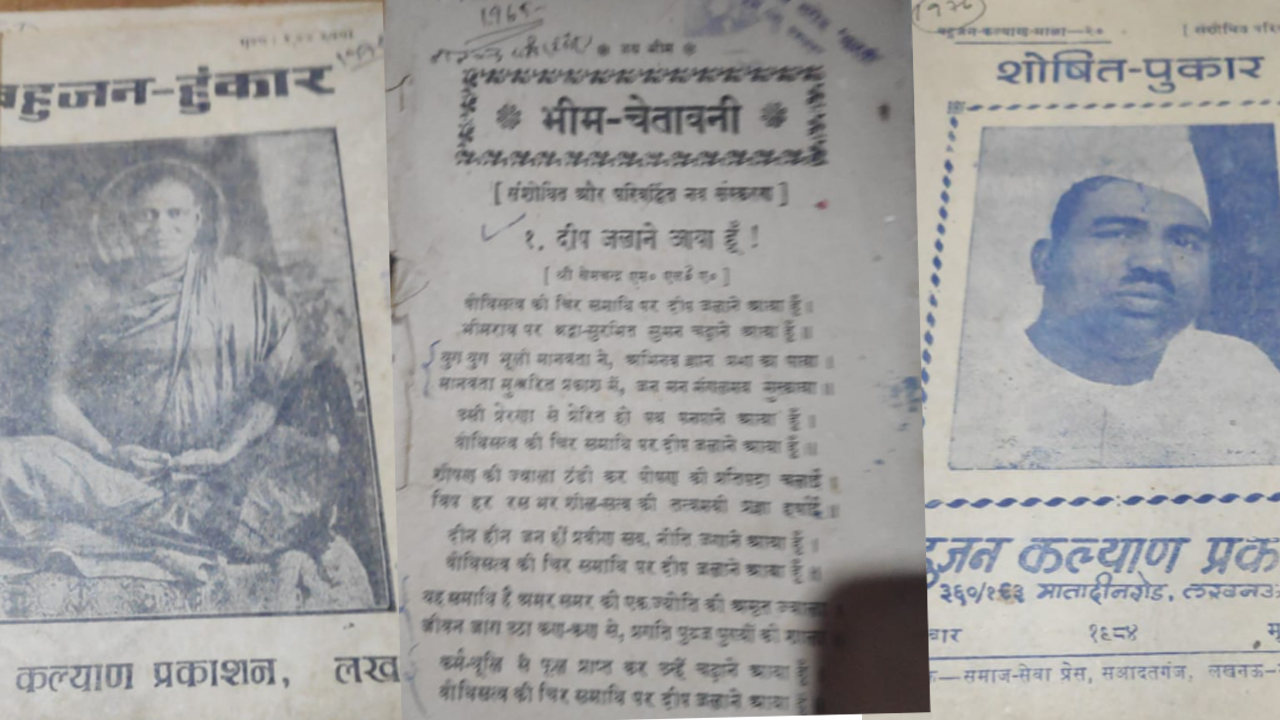

Renu took the genre of reportage to new heights in Hindi literature. No one has been able to match him to date. In his very first reportage, “Vidapat Naach’, he introduced readers to the glorious cultural heritage of Dalits, asked uncomfortable questions about celebrated dancer Uday Shankar and exposed feudal exploitation. The feudal-moneylender nexus forces the Bahujan into a debt trap and enslave them forever. Renu launches a no-holds-barred attack on this inhuman system in his reportage “Baap Re”:

Baap re kaun durgati nahin bhel,

Saat saal ham sood chukaol

Tabahoon urin nahin bahilon

Kolhuk barad san khatlaun raat-din

Karaz badhat hee gel,

Thari bech patwari ke deliyenh

Lota bech chowkidari

Bakri bech sipahi ke deliyenh

Phatak nath girdhari

(Oh my goodness, what all have I endured! I paid interest for seven years, yet I could not be free from debt. I toiled like a bullock day and night but my debt kept on mounting. I sold off my thali (metal plate) and paid the patwari, I sold off my lota (metal mug) and paid the chowkidar. I had a goat, which I sold off and gave the money to the policeman. And here I am – moving about, a complete pauper.)

Clearly, Renu’s commitment towards humans and humanity was unadulterated. From “Nepali Krantikatha” to “Rinjal Dhanjal”, all his writings reflect this commitment. From floods to famines and from political chicanery to a Bihari sweet (Silav ka Khaja), the sweep of his writings is vast. His words are so vivid, his description so lively and his imagery so powerful that even modern reporting, with its live-streaming and more, pales in comparison.

An instance would be in order: “She can hardly keep her feet on the ground. The pain in her stomach is excruciating … four months pregnant … the ball of flesh makes a last-ditch attempt to come out, to see the country of kheer-puri. Bhagiya collapses … the ground gets soaked in warm blood.”

Reportage like “Haddiyon ka Pul” and “Purani Kahani: Naya Path” are about the sharp sting, the deep agony of starvation. Even in these times of “hunger indices”, Renu’s works are a much superior resource to feel the pangs of hunger in times of starvation. The toilers are the worst victims of calamities like floods and famines. Already struggling to make ends meet, they are left without a grain to eat and without a roof over their heads. But the dominant class has no qualms about physically and mentally exploiting the sons of the soil, even when they are enduring such unbearable pain and misery.

“Maybe, they are the Babu log [upper-caste] of Rahikpur! … the Babu log of Rahikpur … young lads, still not even adolescents … they have been making rounds of the Musahar locality for the past four-five days … carrying maize in bags … they say … anyone who wants can have the maize … not a ser or two – but just a few fistfuls! As a loan! But they want interest in advance … their new youth does not differentiate between old and young women or even a child!”

This chilling description in “Haddiyon Ka Pul” bares the macabre import of caste and economic inequality in all its ugliness. Besides participating in the Indian Freedom Struggle, Renu had also joined the armed revolution in Nepal, which he refers to as “Saano Aama” (mother’s younger sister). “Nepali Kranti Katha”, based on his experiences, can be a valuable asset in understanding the geo-political and strategic issues plaguing Indo-Nepal relations.

The flavour of countryside and modernity, of folk lifestyle and folk music, of political corruption and pseudo idealism, which find expression in Maila Aanchal – the novel that catapulted Renu into celebrityhood – can and do find an even greater resonance in today’s globalized world. “Vocal for Local” is a new formulation, but Maila Aanchal implicitly lays down some constructs about the interrelations and the internal contradictions between capital and development. One can find discussion on other dimensions of these constructs in novels like Deerghatapa, Paltu Babu Road and Juloos. Renu depicted the reality of his times with sensitivity and pro-people concern. His approach was informed by a sense of morality and that is why his writings continue to be relevant even today.

Renu struck a balance between the arts and politics. A socialist by ideology, he remained equally committed to his art and politics all his life. That is why his writings consistently reflect the problems of both politics and the arts. Renu was a far-sighted interpreter of the misery and the aspirations of the sons of the soil. Talking about himself, he often used to say, “I endured the barbs of lakhs for your sake.” And the “your” include all the toilers whose labour forms the foundation of the edifice of progress but who remain unknown and unsung. Besides giving voice to the pain of these toilers, Renu also brutally bared the extreme degradation of the patrons of feudal mindset. Sample a dialogue from the short story “Uchchatan”: “Son, what do I say. That day, Misir’s elder son came to fetch milk. The milk had sold out. How could have I given him any? He picked up the pot and while leaving, twisting his tongue, said, “The world has turned upside down. Otherwise, our men have milked women instead of buffaloes in this locality.”

This excerpt is enough to expose the classes that are opposed to caste census today. Renu had genuine empathy for the decrepit and the ignored people and respect and dignity he accorded to them in his writings was bound to incense those who lorded over society. But Renu cared two hoots for his critics. He took his pro-people commitments forward and used his pen to essay the role of a fierce opponent of the status quo.

Renu not only succeeded in turning the “the provinces” (anchal) into the protagonist but also gave centrality to the toilers inhabiting “the provinces”. This could become possible only because he was an author of rare merit. It was his dazzling intellect that lent him the courage to refuse the Padma Shri Award during the Emergency, dubbing it as “Paap Shri”. Sensitivities and sensibilities have more or less the same undertone in different ages and circumstances. That is the reason Renu’s works are still talked about and read and even years after his passing, his popularity and relevance remain intact.

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)