I had been a reader of Hans ever since it resumed publication under the editorship of Rajendra Yadav in 1986. More than the articles and the stories, I was interested in his editorial that went by the name “Teri-Meri Uski Baat”.

It was the 1990s. I was associated with a left-wing students’ organization at Gorakhpur University. Around this time, the Mandal Commission’s report was being implemented, granting 27 per cent reservation to the OBCs in government jobs. That exposed the Savarna face of the university as also of many of my acquaintances, friends and professors, which in turn marked the beginning of my disillusionment with a particular ideology.

We felt that what Indian society needs is modernism and Bahujan renaissance. Only this could help build a movement seeking a complete transformation of Indian society. It was against this backdrop that we zeroed in on establishing a Premchand Sahitya Sansthan – which gave me an opportunity to meet Rajendra Yadav. One of my friends, Katyayani, was active in the feminist movement. Some of her poems were published in Hans and she had requested me to talk to Yadav regarding her remuneration. I did not live in Delhi but was a frequent visitor to the city, and especially Jawaharlal Nehru University, in connection with political activities.

It was October or November. On a balmy afternoon, I found my way to the office of Hans at Daryaganj. My first impression of Rajendra Yadav was that of an elitist, though subsequent interactions demolished this image.

Maybe his sartorial preferences and his stylish manner of smoking the cigar had something to do with that first impression. In Russian novels, the aristocrats and the snobs often smoke cigars and speak French. Maybe that was at the back of my mind. “If I am not wrong, you are Swadesh. Katyayani has sent you. I got a letter from her,” he told me.

Mobile phones were still light years away and even landline phones were few and far between. Letters were the prime means of communication. He inquired about the critic Parmanand Shrivastava and short-story writers Madanmohan and Badshah Hussain Rizvi, all of whom were from Gorakhpur. But I was surprised when he asked about poet and lyricist Devendra Kumar Bengali. Bengali, a Dalit, was undoubtedly a good poet and lyricist and was later compared with Sudama Pandey alias Dhumil, but at that time, few outside Gorakhpur knew him.

Rajendra Yadav was primarily a writer of fiction – short stories and novels. But in my subsequent meetings with him, I realized that he had an abiding interest in all genres of Indian and foreign literature, including novels, stories, plays and poetry. I don’t know whether Katyayani got her dues but I became quite comfortable in my interactions with Rajendra Yadav and the office of Hans became a must-visit for me during my trips to Delhi.

Delhi is a megacity where its residents have little, if any, interest, in meeting and interacting with each other. Well-known authors and poets are even more reclusive and try their best to keep away from ordinary people. But Rajendra Yadav was just the opposite. He loved the crowds. He exulted in mingling with people. Whenever I met him – whether at a seminar or a discussion or a book fair – I always found him surrounded with people. He had a charismatic aura.

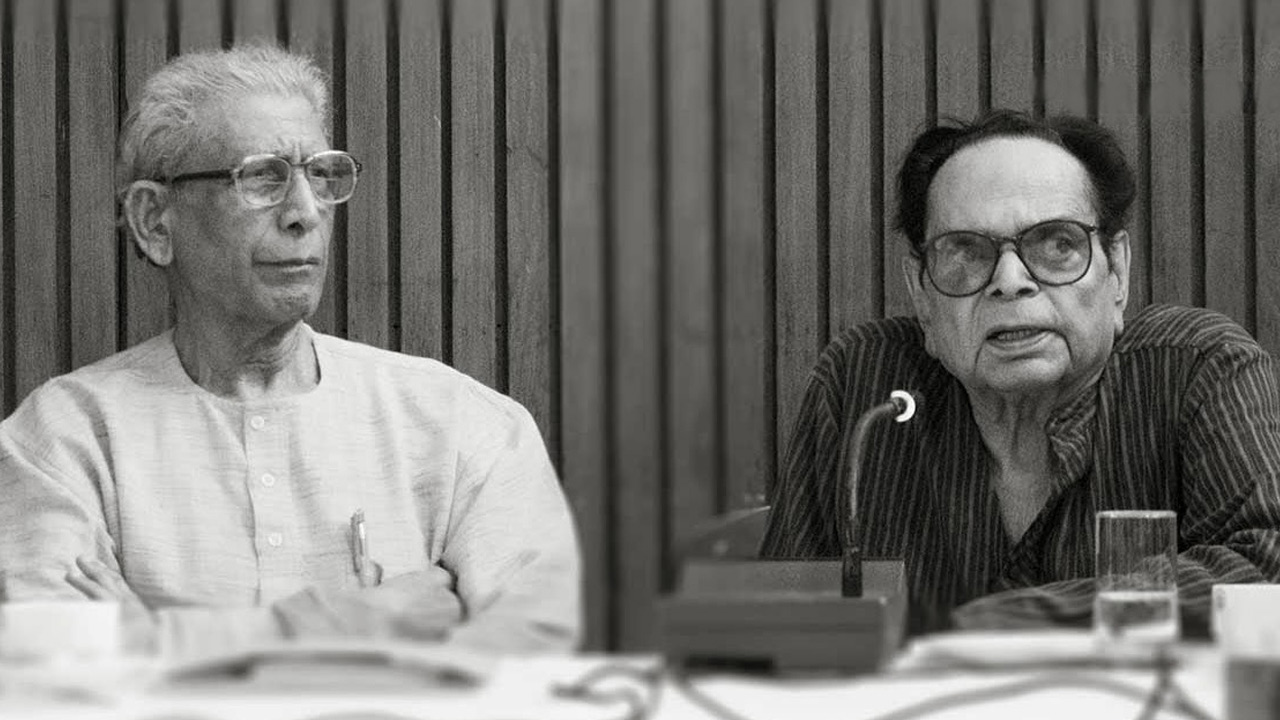

I remember that in the evening of their lives, Namvar Singh and Parmanand Shrivastava were very lonely. But Rajendra Yadav was surrounded with people till his last day.

It is conventional wisdom that authors need calm and peace to allow their creativity to bloom. But Rajendra was an exception.

I remember, once when I was sitting with him at the office of Hans, Giriraj Kishore (author of the novel Pehla Girimitiya) was also there. During our conversation, Rajendra said that the new issue of Hans was ready to go to press but the editorial was yet to be written. He took out a few sheets of paper and began writing the editorial. There was no computer those days. Most people used pen and paper. In about half an hour, he completed the first draft, all the while discussing the Mandal Commission report with us. By the way, the Mandal report was not the topic of the piece. He read out the draft to us. Giriraj pointed out some issues. Yadav tore up the pages he had written and wrote a new draft in about 45 minutes, which he again read out to us. It was indeed very impressive. A clutch of people was always present in his office, discussing and debating literary, political and other issues. Giriraj Kishore was one of them, whom I often saw there. My first meeting with authors like Bhishma Sahani and Ramesh Upadhayay took place at his office.

Rajendra Yadav, as his name indicated, came from a backward caste. But that never reflected in his writings or thinking. However, this changed with Hindu fascist forces rearing their heads after the implementation of the Mandal Commission report. He was anguished and disturbed by the way the Savarna intellectuals, including a sizeable number of leftists, opposed it. This anguish was manifest in his editorials. During this period, he published many collectable special issues of Hans, focused on discourses on women and Dalits. It is heartening to note that his daughter Rachana Yadav later had all those special issues and his key editorials published in the form of a book.

Once I happened to meet Gautam Navlakha at the office of Hans. Navlakha had done his PhD in economics under the supervision of celebrated Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal. During the course of the conversation, I came to know that Navlakha was a distant relative of Rajendra Yadav’s wife Mannu Bhandari. He brought out a Hindi magazine Sancha centred on history, sociology and politics, which was published along with Hans. It ran briefly. There was talk at the time in Delhi’s literary circles that some differences between Yadav and Navlakha had led to the closure of the magazine, though neither of them said a word about it.

Rajendra Yadav was a great advocate of personal freedom and identity. He used to say that in socialist countries like Russia and China, individual freedom and identity had been sacrificed at the altar of collectivism. I used to have fierce arguments with him on this matter. He was a great admirer of Agyeya’s Shekhar: Ek Jeevani. At the time, I was deeply influenced by leftist ideology and was sure that people as a collective should be given precedence over people as individuals. One time, he interrupted a rather heated argument between us by ordering a glass of carrot juice for me. “Cool down a bit and then we’ll talk,” he said. He was like that. He never lost his temper and was a great respecter of his critics. Years after his death, I realized that he was right. Every individual’s personal identity is important. No ideology should ignore the individual’s identity and creativity in the name of collectivism. You cannot reject the creativity of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky or Premchand saying they were merely individuals and did not represent society collectively.

Rajendra Yadav visited Gorakhpur in the 1990s. The occasion was a national seminar on “Premchand aur Bharatiya Upanyas” (Premchand and the Indian Novel) organized by Professor Parmanand Shrivastava, who held the then newly established Premchand chair at the Gorakhpur University. Both Rajendra Yadav and Namvar Singh participated in the seminar. At the seminar, Namvar Singh declared that fiction was dead or was on its deathbed. This incensed Yadav to no end. They attacked each other furiously but afterwards we saw them sitting together and conversing like friends. Many compared them with the two key characters of Bhagwaticharan Verma’s story Do Banke. It was impossible for the feudal mindset to accept that two people could be friends despite sharp ideological differences. Rajendra Yadav fought all his life against this feudal mindset.

Yadav’s visits to Gorakhpur were infrequent but he always maintained literary ties with the city. He was a member of the advisory board of Premchand Sahitya Sansthan and took keen interest in the activities and the progress of the institution. He kept himself abreast of the writers, both young and old, of Gorakhpur as also of the literary activities in the city. He also published Badshah Hussain Rizvi, Madanmohan, Navneet Mishra and many young writers of Gorakhpur.

He always linked the calumny heaped on women writers to the frustrations of male psyche. He waged an incessant battle against the feudal outlook that defined the Hindi belt. He not only published writings by women and Dalit authors in Hans but also turned it into a campaign of sorts, thus widening the scope of literature and redefining its concerns.

Rajendra Yadav did not pull punches in assailing the fascism of the Sangh Parivar. He had to face much flak for describing Hanuman as the first terrorist, and cases were registered against him at many places. He aired his views firmly and courageously and for this reason I liken him to Voltaire. He did not hold grudges against anyone, and so he didn’t have any enemies. Unfortunately, about five years ago, when I made Delhi my permanent abode, he was already gone. He was like a beacon for the extremely backward and feudal society of the Hindi belt.

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)