Many biographies of Dr B.R. Ambedkar have been written. Recently, Shashi Tharoor published Ambedkar: A Life. Tharoor is known for his command of English and his oratory. He is also a prolific author who writes both fiction and non-fiction, the latter being mostly of the variety that appeals to the upper-caste liberals, such as Why I Am A Hindu. Now he has picked up on Ambedkar. The book is divided into two parts – Life and Legacy. What stands out in the narrative is an attempt to provide a political trajectory of Ambedkar.

While Tharoor often describes Ambedkar as a global icon, he simultaneously limits his contribution to his work among the Untouchables or Dalits. In his previous books Why I Am A Hindu (2018) and The Hindu Way: An Introduction to Hinduism (2019) Tharoor advocated a Hindu way of life. In 2022, he turned to Ambedkar while admitting that he has “become acutely conscious of the fact that someone will object to this book on the basic ground that I am not a Dalit”. Given such a disclaimer, the argument and idea of the book becomes problematic. A scholar on the relevant subject can understand the intention behind the writing of a book. A person who justifies being a practising Hindu in Why I Am A Hindu does not explain why he is writing about Ambedkar. The inference the reader draws is that Tharoor sensed that there was a market for the book and went on to write it.

A note on sources

Writing history is a herculean task. It is a time-consuming, painstaking and exhausting process. For a scholar, it takes several years to understand the process of writing history. Tharoor clearly lacks the understanding of history writing. He extensively quotes Dhananjay Keer, Vasant Moon, M.L. Sahare, Gail Omvedt and Christophe Jaffrelot instead of going into archival sources on the subject matter. This appears to be mostly a work of replication, relying largely on secondary sources. Some portions from the sources have been presented with modifications and without attribution. Ambedkar delivered many speeches in Marathi, wrote editorials and pieces in his own newspapers and magazines. These writings and speeches have been compiled and edited by Hari Narke, which is available in Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches (BAWS) Volume 18 in three parts and Volume 19. There are reports and documents related to Ambedkar available in different archives but Tharoor primarily relied on sources available in English, that too online, which are easily accessible. The Marathi sources would have enriched Tharoor’s work. A historian provides an array of different sources to substantiate their argument, but Tharoor chose the easy way out.

Ambedkar’s Riddle of Hinduism was “an assault on the religion he had chosen to abandon” (p 133), writes Tharoor in Chapter 5 titled “Triumph and Disillusion 1946-1956”. Ambedkar cited references in support of his arguments in that book, and it was not an assault but a treatise on Hinduism. Ambedkar’s unpublished works also exist, and not just the 17500 pages of Ambedkar’s writings and speeches, as the book’s author enumerates in the sixth chapter titled “A Life Well-Lived” (p 141). It seems that Tharoor has only read “Babasaheb Ambedkar Writing and Speeches” published by the Publication Division, Government of Maharashtra. Some sources haven’t been properly cited. For example, an article titled “Ambedkar: A jurist with no equals” written by me and published on ForwardPress.in has been mentioned as “A jurist with no equals”. Another example of improper citation is “Parekh, Bhiku, ‘The Intellectual and Political Legacy of B. R. Ambedkar’, in Aakash Singh Rathore (ed), B.R. Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2021”. Here the volume (No 1) is not mentioned and the first name of the author is misspelt – it is “Bhikhu”, not “Bhiku”.

Four ‘flaws’

There are four flaws identified by Tharoor in Ambedkar’s life. The first one is related to the Adivasis. Tharoor writes that Ambedkar considered Adivasis “savages” who needed “civilising”. He writes, “It demeans Ambedkar to have spoken with language bordering on prejudice and racism about the Adivasi people” (p 171). While arguing so, it seems that Tharoor overlooked the Constituent Assembly debates and even the Constitution in which Ambedkar included articles for the protection of the rights of the Adivasis and to ensure their representation in the State. Hence, there was no attempt to understand the development of Ambedkar’s thinking on Adivasis.

Tharoor finds the second flaw in Ambedkar’s critique of Hinduism. He relies on political theorist Bhikhu Parekh to criticize Ambedkar. Parekh calls Ambedkar’s view on Hinduism “quasi-Manichaean” – meaning he saw everything in black and white (good and evil) and dismissed the grey areas in between – and Tharoor writes that “Ambedkar’s language about Hindu and Hinduism is too sweepingly scathing” (p 172). Ambedkar wrote on many aspects of Hinduism, which Tharoor describes as a “great religion” (p 174). Tharoor quotes Ambedkar selectively on Hinduism without even giving any context to substantiate his arguments. Reducing a person to a few quotes is not a scholarly enterprise. Ambedkar’s “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development”, “Annihilation of Caste” and “Philosophy of Hinduism” are well-researched writings. Only after reading these and other scholarly works could the author have grasped Ambedkar’s approach on Hinduism. There is no duality in Ambedkar’s view on Hinduism as he writes in “Annihilation of Caste” that “I have, therefore, no hesitation in saying that such a religion must be destroyed, and I say there is nothing irreligious in working for the destruction of such a religion. Indeed I hold that it is your bounden duty to tear off the mask, to remove the misrepresentation that is caused by misnaming this Law as Religion.”

Third, Tharoor writes that Ambedkar wasn’t gracious in his criticism of Gandhi, even after Gandhi’s death. Tharoor uses the honorific “Mahatma” for M. K. Gandhi, whereas he refrains from using “Babasaheb” or “Dr” for B. R. Ambedkar. There is nothing wrong in using just “Ambedkar”, but unequal treatment gives away the author’s bias. Titles like “Mahatma” and “Babasaheb” were given by admirers of these personalities but Tharoor does not seem to appreciate this fact. A decade ago, Arundhati Roy wrote the essay “The Doctor and the Saint” as introduction to an annotated edition of Ambedkar’s “Annihilation of Caste”, the Doctor being Ambedkar and the Saint being M. K. Gandhi. Similarly, Tharoor seems to be unquestioningly using the title “Mahatma’ for Gandhi, who is a central character in his criticism of Ambedkar. Tharoor refers to the Ambedkar-Gandhi debate on Hinduism. He comes across as patronizing to Ambedkar about his critique of Gandhi. He attempts to defend Gandhi and Hinduism by quoting Ambedkar on Hinduism out of context. He is heavily dependent on Parekh’s work to show Gandhi’s role in eradicating untouchability from Hinduism. However, Ambedkar’s agenda was not only eradication of untouchability but the annihilation of caste, since caste is at the heart of discrimination and exclusion. Ambedkar wanted inter-caste marriages, inter-dining whereas Gandhi took no stand on eradicating caste till his last breath. He writes without any basis that Gandhi ensured Ambedkar’s presence in the drafting committee of the Constitution and his becoming the first union law minister of independent India. Tharoor writes that “he [Ambedkar] could not rise above his bitterness to show any generosity of spirit towards the Mahatma” (p 178). Why does Tharoor refrain from criticizing Gandhi? He tries to defend Gandhi emotionally instead of rationally, logically answering Ambedkar’s questions and grievances directed at Gandhi. He presents the Gandhi-Congress-centric narrative with Ambedkar in the periphery. The author fails miserably in finding flaws in Ambedkar through his own reading of the Ambedkar-Gandhi debate and sticks to just a chronicle of the debate.

Fourth, according to Tharoor, Ambedkar strongly believed in “statism”, held “absolute faith in the institution [State]” and wanted a “strong central government” for the empowerment of Dalits (p 178). The “evidence” that Tharoor has given to prove his arguments seems naïve, and his criticism is vague. Ambedkar wanted a strong government but that he held absolute faith in the State as an institution emanates from a wrong understanding of Ambedkar, who remained a pragmatist all his life. Observing his political life, from 1918 until his death, his diverse political activities clearly show that he was challenging the existing government, presenting memorandums, and sending grievances to the government. Ambedkar’s initiatives like the People’s Education Society and its different colleges and other educational institution and centres; The Bombay Scheduled Caste Improvement Trust, The Scheduled Castes Federation; his resignation as law minister on the issue of Hindu Code Bill; and conversion into Buddhism and the formation of the Republican Party of India showed his belief that if the government failed in its duty towards citizens, then citizens should intervene.

Tharoor has a problem with Ambedkar’s attire. Toeing Parekh’s line, he writes, “The image of Ambedkar, in his suit and tie, issuing ‘progressive’ modern diktats to ignorant dhoti-clad bigots covered in the dust and grime of their rural backwardness, is not a reassuring one, evoking the authoritarian fantasies of other modernizing autocracies, rather than the evolutionary change, anchored in local realities, that a democracy requires for its development.” (p 178) There is no reference to Ambedkar’s writings on the issue. It seems that Tharoor momentarily forgot the importance of symbolism in politics. Going through Ambedkar’s writings and speeches, one can easily conclude Ambedkar’s emphasis on being neat and clean, and maintaining hygiene. Moreover, a suit was, still is, the common attire for an advocate, and Ambedkar was an advocate. Besides, he spent years in the United States and England for higher education, which is when he started wearing a suit. Given this sartorial history, Tharoor describing Ambedkar’s attire as “evoking the authoritarian fantasies of other modernizing autocracies” makes no sense. This is a typical upper-caste mentality prevalent even today. They find it difficult to accept a person from a Dalit community dressing well.

Tharoor writes that if Ambedkar and Savarkar were alive today, they would hold similar views on the issue of the cow. Savarkar “urged Hindus to care for the cow because of its utility, rather than worship it” (p 192). Muslims and Dalits have been facing assault for “allegedly transporting or consuming the holy animal” (p 192). By referring to the cow as a “holy animal”, Tharoor seems to be agreeing with the propounders of Hindutva. His Hindutva is evident when he overlooks India’s different beliefs and diverse food culture. Tharoor could have presented ideological stands of both the historical figures instead of limiting the endeavour to politics on the cow. Tharoor claims that the Bharatiya Janata Party is politicizing the cow today but does not mention that the electoral symbol of Indira Gandhi’s Congress between 1969 and 1978 was a cow and its calf.

Character assassination

Citing references to what Ambedkar’s friend Naval Bhathena and actor Dilip Kumar have allegedly said, Tharoor paints a pitiable plight of Ambedkar as someone who was helpless and asking for donations from different people. The references Tharoor has used here are controversial. Tharoor’s intention seems to be to prove that Ambedkar was full of bitterness and always involved in disputation.

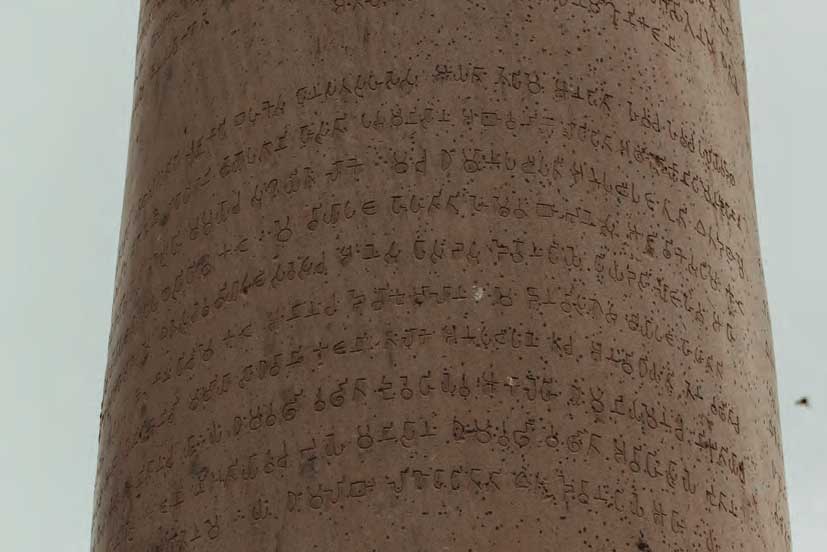

Tharoor writes “human relationships did not seem to matter enough to him; only ideas did. He neglected his wife and children even while he worried about them. He had a legion of admirers but very few friends.” (p 134) Tharoor forgets to mention how Ambedkar struggled for a livelihood. When Ambedkar began his career as a lawyer in Bombay, he was not getting cases due to his so-called low-caste status. While describing the statue of Ambedkar in Chapter Five titled “Triumph and Disillusion 1946-1956” he writes about ‘a stocky balding figure in a suit and tie clutching a law book meant to represent the constitution’ (p 135). This is a demeaning view that someone from a privileged caste Hindu background may have of Ambedkar and the Constitution that protects the rights of the Indian citizen irrespective of their socio-economic and political status. Such an analysis is nothing but an attempt at character assassination of the head of the committee that drafted the Constitution and the first law minister of independent India.

In his biography of Ambedkar, Shashi Tharoor thus repackages existing literature on Ambedkar and makes half-baked arguments without contextualizing the words and deeds of Ambedkar.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)